Định luật Titius–Bode

Định luật Titius–Bode (đôi khi còn được gọi ngắn gọn là Đinh luật Bode) là một giả thuyết cũ nhằm xác định quỹ đạo của các hành tinh khi quay quanh một thiên thể khác, bao gồm cả quỹ đạo của Mặt trời và quỹ đạo tại Bán trục lớn của các hành tinh trong Hệ Mặt Trời được miêu tả bởi công thức truy hồi ở dưới. Giả thuyết này đã dự đoán chính xác quỹ đạo của Tiểu hành tinh Ceres và Sao Thiên Vương (Uranus), nhưng lại thất bại trong việc dự đoán quỹ đạo của Sao Hải Vương (Neptune) và Sao Diêm Vương (Pluto). Định luật này được đặt theo tên của hai nhà khoa học Johann Daniel Titius và Johann Elert Bode.

Công thức[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Định luật liên quan tới bán trục lớn của các hành tinh trong Hệ Mặt Trời tính theo đơn vị bằng 10 lần Đơn vị thiên văn - coi bán trục lớn của Trái Đất có giá trị là 10:

với ngoại trừ số đầu tiên, mỗi giá trị sau đều bằng hai lần giá trị liền trước.

Một cách khác để biểu diễn công thức: với .

Hoặc kết quả có thể chia cho 10 để chuyển sang Đơn vị thiên văn (AU), với công thức sau:

với Với các hành tinh bên ngoài, mỗi hành tinh được dự đoán là có khoảng cách từ Mặt Trời xa khoảng gấp 2 lần khoảng cách của hành tinh trước.

Lịch sử[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The first mention of a series approximating Bode's Law is found in David Gregory's The Elements of Astronomy, published in 1715. In it, he says, "...supposing the distance of the Earth from the Sun to be divided into ten equal Parts, of these the distance of Mercury will be about four, of Venus seven, of Mars fifteen, of Jupiter fifty two, and that of Saturn ninety six."[1] A similar sentence, likely paraphrased from Gregory,[1] appears in a work published by Christian Wolff in 1724.

In 1764, Charles Bonnet said in his Contemplation de la Nature that, "We know seventeen planets that enter into the composition of our solar system [that is, major planets and their satellites]; but we are not sure that there are no more."[1] To this, in his 1766 translation of Bonnet's work, Johann Daniel Titius added the following unattributed addition, removed to a footnote in later editions:

Take notice of the distances of the planets from one another, and recognize that almost all are separated from one another in a proportion which matches their bodily magnitudes. Divide the distance from the Sun to Saturn into 100 parts; then Mercury is separated by four such parts from the Sun, Venus by 4+3=7 such parts, the Earth by 4+6=10, Mars by 4+12=16. But notice that from Mars to Jupiter there comes a deviation from this so exact progression. From Mars there follows a space of 4+24=28 such parts, but so far no planet was sighted there. But should the Lord Architect have left that space empty? Not at all. Let us therefore assume that this space without doubt belongs to the still undiscovered satellites of Mars, let us also add that perhaps Jupiter still has around itself some smaller ones which have not been sighted yet by any telescope. Next to this for us still unexplored space there rises Jupiter's sphere of influence at 4+48=52 parts; and that of Saturn at 4+96=100 parts.

In 1772, Johann Elert Bode, aged only twenty-five, completed the second edition of his astronomical compendium Anleitung zur Kenntniss des gestirnten Himmels, into which he added the following footnote, initially unsourced, but credited to Titius in later versions:[2]

This latter point seems in particular to follow from the astonishing relation which the known six planets observe in their distances from the Sun. Let the distance from the Sun to Saturn be taken as 100, then Mercury is separated by 4 such parts from the Sun. Venus is 4+3=7. The Earth 4+6=10. Mars 4+12=16. Now comes a gap in this so orderly progression. After Mars there follows a space of 4+24=28 parts, in which no planet has yet been seen. Can one believe that the Founder of the universe had left this space empty? Certainly not. From here we come to the distance of Jupiter by 4+48=52 parts, and finally to that of Saturn by 4+96=100 parts.

When originally published, the law was approximately satisfied by all the known planets — Mercury through Saturn — with a gap between the fourth and fifth planets. It was regarded as interesting, but of no great importance until the discovery of Uranus in 1781 which happens to fit neatly into the series. Based on this discovery, Bode urged a search for a fifth planet. Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt, was found at Bode's predicted position in 1801. Bode's law was then widely accepted until Neptune was discovered in 1846 and found not to satisfy Bode's law. Simultaneously, the large number of known asteroids in the belt resulted in Ceres no longer being considered a planet at that time. Bode's law was discussed as an example of fallacious reasoning by the astronomer and logician Charles Sanders Peirce in 1898.[3]

The discovery of Pluto in 1930 confounded the issue still further. While nowhere near its position as predicted by Bode's law, it was roughly at the position the law had predicted for Neptune. However, the subsequent discovery of the Kuiper belt, and in particular of the object Eris, which is larger than Pluto yet does not fit Bode's law, have further discredited the formula.[4]

Dữ liệu[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

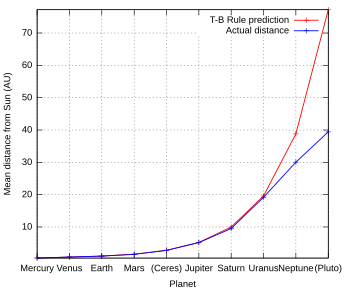

Đây là khoảng cách của các hành tinh trong Hệ Mặt Trời, theo con số tính toán và con số thực tế:

| Planet | k | T-B rule distance (AU) | Real distance (AU) | % error (using real distance as the accepted value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0 | 0.4 | 0.39 | 2.56% |

| Venus | 1 | 0.7 | 0.72 | 2.78% |

| Earth | 2 | 1.0 | 1.00 | 0.00% |

| Mars | 4 | 1.6 | 1.52 | 5.26% |

| Ceres1 | 8 | 2.8 | 2.77 | 1.08% |

| Jupiter | 16 | 5.2 | 5.20 | 0.00% |

| Saturn | 32 | 10.0 | 9.54 | 4.82% |

| Uranus | 64 | 19.6 | 19.2 | 2.08% |

| Neptune | 128 | 38.8 | 30.06 | 29.08% |

| Pluto2 | 256 | 77.22 | 39.44 | 95.75% |

1 Ceres was considered a small planet from 1801 until the 1860s. Pluto was considered a planet from 1930 to 2006. Both are now classified as dwarf planets.

2 While the difference between the T-B rule distance and real distance seems very large here, if Neptune is 'skipped,' the T-B rule's distance of 38.8 is quite close to Pluto's real distance with an error of only 1.62%.

Giải thích[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

There is no solid theoretical explanation of the Titius–Bode law, but if there is one it is possibly a combination of orbital resonance and shortage of degrees of freedom: any stable planetary system has a high probability of satisfying a Titius–Bode-type relationship. Since it may simply be a mathematical coincidence rather than a "law of nature", it is sometimes referred to as a rule instead of "law".[5] However, astrophysicist Alan Boss states that it is just a coincidence, and the planetary science journal Icarus no longer accepts papers attempting to provide improved versions of the law.[4]

Orbital resonance from major orbiting bodies creates regions around the Sun that are free of long-term stable orbits. Results from simulations of planetary formation support the idea that a randomly chosen stable planetary system will likely satisfy a Titius–Bode law.

Dubrulle and Graner[6][7] have shown that power-law distance rules can be a consequence of collapsing-cloud models of planetary systems possessing two symmetries: rotational invariance (the cloud and its contents are axially symmetric) and scale invariance (the cloud and its contents look the same on all scales), the latter being a feature of many phenomena considered to play a role in planetary formation, such as turbulence.

Lunar systems and other planetary systems[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

There is a decidedly limited number of systems on which Bode's law can presently be tested. Two of the solar planets have a number of big moons that appear possibly to have been created by a process similar to that which created the planets themselves. The four big satellites of Jupiter and the biggest inner satellite, Amalthea, cling to a regular, but non-Bode, spacing with the four innermost locked into orbital periods that are each twice that of the next inner satellite. The big moons of Uranus have a regular, but non-Bode, spacing.[8] However, according to Martin Harwit, "a slight new phrasing of this law permits us to include not only planetary orbits around the Sun, but also the orbits of moons around their parent planets."[9] The new phrasing is known as Dermott's law.

Of the recent discoveries of extrasolar planetary systems, few have enough known planets to test whether similar rules apply to other planetary systems. An attempt with 55 Cancri suggested the equation a = 0.0142 e 0.9975 n, and predicts for n = 5 an undiscovered planet or asteroid field at 2 AU.[10] This is controversial.[11] Furthermore the orbital period and semimajor axis of the innermost planet in the 55 Cancri system have been significantly revised (from 2.817 days to 0.737 days and from 0.038 AU to 0.016 AU respectively) since the publication of these studies.[12]

Recent astronomical research suggests that planetary systems around some other stars may fit Titius–Bode-like laws.[13][14] Bovaird and Lineweaver[15] applied a generalized Titius-Bode relation to 68 exoplanet systems which contain four or more planets. They showed that 96% of these exoplanet systems adhere to a generalized Titius-Bode relation to a similar or greater extent than the Solar System does. The locations of potentially undetected exoplanets are predicted in each system.

Subsequent research managed to detect five planet candidates from predicted 97 planets from the 68 planetary systems. The study showed that the actual number of planets could be larger. The occurrence rate of Mars and Mercury sized planets are currently unknown so many planets could be missed due to their small size. Other reasons were accounted to planet not transiting the star or the predicted space being occupied by circumstellar disks. Despite this, the number of planets found with Titius-Bode law predictions were still lower than expected.[16]

Tham khảo[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- ^ a b c “Dawn: A Journey to the Beginning of the Solar System”. Space Physics Center: UCLA. 2005. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 24 tháng 5 năm 2012. Truy cập ngày 3 tháng 11 năm 2007.

- ^ Hoskin, Michael (ngày 26 tháng 6 năm 1992). “Bodes' Law and the Discovery of Ceres”. Observatorio Astronomico di Palermo "Giuseppe S. Vaiana". Truy cập ngày 5 tháng 7 năm 2007.

- ^ Pages 194-196 in

- Peirce, Charles Sanders, Reasoning and the Logic of Things, The Cambridge Conference Lectures of 1898, Kenneth Laine Ketner, ed., intro., and Hilary Putnam, intro., commentary, Harvard, 1992, 312 pages, hardcover (ISBN 978-0674749665, ISBN 0-674-74966-9), softcover (ISBN 978-0-674-74967-2, ISBN 0-674-74967-7) HUP catalog page.

- ^ a b Alan Boss (tháng 10 năm 2006). “Ask Astro”. Astronomy. 30 (10): 70.

- ^ Carroll, Bradley W.; Ostlie, Dale A. (2007). An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics . Addison-Wesley. tr. 716–717. ISBN 0-8053-0402-9.

- ^ F. Graner, B. Dubrulle (1994). “Titius-Bode laws in the solar system. Part I: Scale invariance explains everything”. Astronomy and Astrophysics. 282: 262–268. Bibcode:1994A&A...282..262G.

- ^ B. Dubrulle, F. Graner (1994). “Titius–Bode laws in the solar system. Part II: Build your own law from disk models”. Astronomy and Astrophysics. 282: 269–276. Bibcode:1994A&A...282..269D.

- ^ Cohen, Howard L. “The Titius-Bode Relation Revisited”. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 28 tháng 9 năm 2007. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 2 năm 2008.

- ^ Harwit, Martin. Astrophysical Concepts (Springer 1998), pages 27-29.

- ^ Arcadio Poveda and Patricia Lara (2008). “The Exo-Planetary System of 55 Cancri and the Titus-Bode Law” (PDF). Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica (44): 243–246.

- ^ Ivan Kotliarov (ngày 21 tháng 6 năm 2008). "The Titius-Bode Law Revisited But Not Revived". arΧiv:0806.3532 [physics.space-ph].

- ^ Rebekah I. Dawson, Daniel C. Fabrycky (2010). “Title: Radial velocity planets de-aliased. A new, short period for Super-Earth 55 Cnc e”. Astrophysical Journal. 722: 937–953. arXiv:1005.4050. Bibcode:2010ApJ...722..937D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/722/1/937.

- ^ “The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets” (PDF). ngày 23 tháng 8 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 8 năm 2010. Section 8.2: "Extrasolar Titius-Bode-like laws?"

- ^ P. Lara, A. Poveda, and C. Allen. On the structural law of exoplanetary systems. AIP Conf. Proc. 1479, 2356 (2012); doi: 10.1063/1.4756667

- ^ Timothy Bovaird, Charles H. Lineweaver (2013). “Title: Exoplanet predictions based on the generalized Titius–Bode relation”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. arXiv:1304.3341. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.tmp.2080B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1357.

- ^ “[1405.2259] Testing the Titius”. Truy cập 8 tháng 2 năm 2015.

Xem thêm[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Đọc thêm[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- The ghostly hand that spaced the planets New Scientist ngày 9 tháng 4 năm 1994, p13

- Plants and Planets: The Law of Titius-Bode explained by H.J.R. Perdijk