Khác biệt giữa bản sửa đổi của “Đạo hàm riêng”

Không có tóm lược sửa đổi |

|||

| Dòng 41: | Dòng 41: | ||

:<math>\frac{\part f}{\part y}(x,y) = x + 2y.\,</math> |

:<math>\frac{\part f}{\part y}(x,y) = x + 2y.\,</math> |

||

Đây là đạo hàm riêng của ''f'' theo biến số ''y''. Ổ đây ∂ được gọi là '''ký hiệu đạo hàm riêng'''. |

|||

This is the partial derivative of ''f'' with respect to ''y''. Here ∂ is a rounded ''d'' called the '''partial derivative symbol'''. To distinguish it from the letter ''d'', ∂ is sometimes pronounced "del" or "partial" instead of "dee". |

|||

Một cách tổng Quát, '''đạo hàm riêng''' của một hàm số ''f''(''x''<sub>1</sub>,...,''x''<sub>''n''</sub>) theo hướng ''x<sub>i</sub>'' at the tại điểm (''a''<sub>1</sub>,...,''a<sub>n</sub>'') được định nghĩa là: |

|||

:<math>\frac{\part f}{\part x_i}(a_1,\ldots,a_n) = \lim_{h \to 0}\frac{f(a_1,\ldots,a_i+h,\ldots,a_n) - f(a_1,\ldots, a_i, \dots,a_n)}{h}.</math> |

:<math>\frac{\part f}{\part x_i}(a_1,\ldots,a_n) = \lim_{h \to 0}\frac{f(a_1,\ldots,a_i+h,\ldots,a_n) - f(a_1,\ldots, a_i, \dots,a_n)}{h}.</math> |

||

Trong tỷ số bên trên, tất cả các biến ngoại trừ ''x<sub>i</sub>'' được giữ cố định. Do vậy ta chỉ có hàm số theo một biến <math>f_{a_1,\ldots,a_{i-1},a_{i+1},\ldots,a_n}(x_i) = f(a_1,\ldots,a_{i-1},x_i,a_{i+1},\ldots,a_n)</math>, và do định nghĩa,, |

|||

:<math>\frac{df_{a_1,\ldots,a_{i-1},a_{i+1},\ldots,a_n}}{dx_i}(x_i) = \frac{\part f}{\part x_i}(a_1,\ldots,a_n).</math> |

:<math>\frac{df_{a_1,\ldots,a_{i-1},a_{i+1},\ldots,a_n}}{dx_i}(x_i) = \frac{\part f}{\part x_i}(a_1,\ldots,a_n).</math> |

||

| Dòng 53: | Dòng 53: | ||

In other words, the different choices of ''a'' index a family of one-variable functions just as in the example above. This expression also shows that the computation of partial derivatives reduces to the computation of one-variable derivatives. |

In other words, the different choices of ''a'' index a family of one-variable functions just as in the example above. This expression also shows that the computation of partial derivatives reduces to the computation of one-variable derivatives. |

||

An important example of a function of several variables is the case of a [[scalar-valued function]] ''f''(''x''<sub>1</sub>,...''x''<sub>''n''</sub>) on a domain in Euclidean space '''R'''<sup>''n''</sup> (e.g., on '''R'''<sup>2</sup> or '''R'''<sup>3</sup>). In this case ''f'' has a partial derivative ∂''f''/∂''x''<sub>''j''</sub> with respect to each variable ''x''<sub>''j''</sub>. At the point ''a'', these partial derivatives define the vector |

An important example of a function of several variables is the case of a [[scalar-valued function]] ''f''(''x''<sub>1</sub>,...''x''<sub>''n''</sub>) on a domain in Euclidean space '''R'''<sup>''n''</sup> (e.g., on '''R'''<sup>2</sup> or '''R'''<sup>3</sup>). In this case L''f'' has a partial derivative ∂''f''/∂''x''<sub>''j''</sub> with respect to each variable ''x''<sub>''j''</sub>. At the point ''a'', these partial derivatives define the vector |

||

:<math>\nabla f(a) = \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}(a), \ldots, \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n}(a)\right).</math> |

:<math>\nabla f(a) = \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}(a), \ldots, \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n}(a)\right).</math> |

||

Phiên bản lúc 13:39, ngày 12 tháng 5 năm 2012

Trong toán học, đạo hàm riêng của một hàm số đa biến là đạo hàm theo một biến, các biến khác được xem như là hằng số(khác vớiđạo hàm toàn phần, khi tất cả các biến đều biến thiên). Đạo hàm riêng được sử dụng trong giải tích vector và hình học vi phân.

Đạo hàm riêng của f đối với biến x được kí hiệu khác nhau bởi

Kí hiệu của đạo hàm riêng là∂. Kí hiệu này được giới thiệu bởi Adrien-Marie Legendrevà được chấp nhận rộng rãi sau khi nó được giới thiệu lại bởi Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi.[1]

Định nghĩa

Ví dụ sau sẽ giúp giải thích định nghĩa của đạo hàm riêng theo biến y.Giả sử một hàm theo hai biến x,y được xem như là một họ các hàm theo y được đánh số theo x

Nói một cách khác, mỗi giá trị của x định nghĩa một hàm số, ký hiệu là fx, mà nó là hàm số một biến. Nghĩa là

Một khi giá trị của x được chọn, ví dụ là a, thì f(x,y) xác định một hàm số fa

Trong công thức này, a làhằng số, không phải làbiến số, do đó fa là một hàm số một biến và do vậy ta có thể sử dụng định nghĩa đạo hàm cho hàm một biến:

Quy trình trên có thể được áp dụng cho bất cứ lựa chọn nào của a. Khi đem gộp lại tất cả những đạo hàm đó ta có được sự biến thiên của hàm số f theo hướng của y :

Đây là đạo hàm riêng của f theo biến số y. Ổ đây ∂ được gọi là ký hiệu đạo hàm riêng.

Một cách tổng Quát, đạo hàm riêng của một hàm số f(x1,...,xn) theo hướng xi at the tại điểm (a1,...,an) được định nghĩa là:

Trong tỷ số bên trên, tất cả các biến ngoại trừ xi được giữ cố định. Do vậy ta chỉ có hàm số theo một biến , và do định nghĩa,,

In other words, the different choices of a index a family of one-variable functions just as in the example above. This expression also shows that the computation of partial derivatives reduces to the computation of one-variable derivatives.

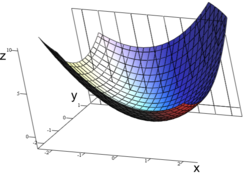

An important example of a function of several variables is the case of a scalar-valued function f(x1,...xn) on a domain in Euclidean space Rn (e.g., on R2 or R3). In this case Lf has a partial derivative ∂f/∂xj with respect to each variable xj. At the point a, these partial derivatives define the vector

This vector is called the gradient of f at a. If f is differentiable at every point in some domain, then the gradient is a vector-valued function ∇f which takes the point a to the vector ∇f(a). Consequently, the gradient produces a vector field.

A common abuse of notation is to define the del operator (∇) as follows in three-dimensional Euclidean space R3 with unit vectors :

Or, more generally, for n-dimensional Euclidean space Rn with coordinates (x1, x2, x3,...,xn) and unit vectors ():

Examples

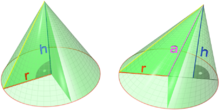

The volume V of a cone depends on the cone's height h and its radius r according to the formula

The partial derivative of V with respect to r is

which represents the rate with which a cone's volume changes if its radius is varied and its height is kept constant. The partial derivative with respect to h is

which represents the rate with which the volume changes if its height is varied and its radius is kept constant.

By contrast, the total derivative of V with respect to r and h are respectively

and

The difference between the total and partial derivative is the elimination of indirect dependencies between variables in partial derivatives.

If (for some arbitrary reason) the cone's proportions have to stay the same, and the height and radius are in a fixed ratio k,

This gives the total derivative with respect to r:

Which simplifies to:

Similarly, the total derivative with respect to h is:

Equations involving an unknown function's partial derivatives are called partial differential equations and are common in physics, engineering, and other sciences and applied disciplines.

Notation

For the following examples, let f be a function in x, y and z.

First-order partial derivatives:

Second-order partial derivatives:

Second-order mixed derivatives:

Higher-order partial and mixed derivatives:

When dealing with functions of multiple variables, some of these variables may be related to each other, and it may be necessary to specify explicitly which variables are being held constant. In fields such as statistical mechanics, the partial derivative of f with respect to x, holding y and z constant, is often expressed as

Antiderivative analogue

There is a concept for partial derivatives that is analogous to antiderivatives for regular derivatives. Given a partial derivative, it allows for the partial recovery of the original function.

Consider the example of . The "partial" integral can be taken with respect to x (treating y as constant, in a similar manner to partial derivation):

Here, the "constant" of integration is no longer a constant, but instead a function of all the variables of the original function except x. The reason for this is that all the other variables are treated as constant when taking the partial derivative, so any function which does not involve will disappear when taking the partial derivative, and we have to account for this when we take the antiderivative. The most general way to represent this is to have the "constant" represent an unknown function of all the other variables.

Thus the set of functions , where g is any one-argument function, represents the entire set of functions in variables x,y that could have produced the x-partial derivative 2x+y.

If all the partial derivatives of a function are known (for example, with the gradient), then the antiderivatives can be matched via the above process to reconstruct the original function up to a constant.

See also

Notes

- ^ Jeff Miller (14 tháng 6 năm 2009). “Earliest Uses of Symbols of Calculus”. Earliest Uses of Various Mathematical Symbols. Truy cập ngày 20 tháng 2 năm 2010.

External links

- Partial Derivatives at MathWorld

![{\displaystyle \nabla ={\bigg [}{\frac {\partial }{\partial x}}{\bigg ]}\mathbf {\hat {i}} +{\bigg [}{\frac {\partial }{\partial y}}{\bigg ]}\mathbf {\hat {j}} +{\bigg [}{\frac {\partial }{\partial z}}{\bigg ]}\mathbf {\hat {k}} }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d3a85a7de9ee9f583d152b6e08c8d0e34afafeff)

![{\displaystyle \nabla =\sum _{j=1}^{n}{\bigg [}{\frac {\partial }{\partial x_{j}}}{\bigg ]}\mathbf {{\hat {e}}_{j}} ={\bigg [}{\frac {\partial }{\partial x_{1}}}{\bigg ]}\mathbf {{\hat {e}}_{1}} +{\bigg [}{\frac {\partial }{\partial x_{2}}}{\bigg ]}\mathbf {{\hat {e}}_{2}} +{\bigg [}{\frac {\partial }{\partial x_{3}}}{\bigg ]}\mathbf {{\hat {e}}_{3}} +\dots +{\bigg [}{\frac {\partial }{\partial x_{n}}}{\bigg ]}\mathbf {{\hat {e}}_{n}} }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2c83e9cb78d0e11d52d23d1eebfd3b90e3bea09f)