Thymol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

5-Methyl-2-(propan-2-yl)phenol | |

| Other names

2-Isopropyl-5-methylphenol, isopropyl-m-cresol, 1-methyl-3-hydroxy-4-isopropylbenzene, 3-methyl-6-isopropylphenol, 5-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)phenol, 5-methyl-2-isopropyl-1-phenol, 5-methyl-2-isopropylphenol, 6-isopropyl-3-methylphenol, 6-isopropyl-m-cresol, Apiguard, NSC 11215, NSC 47821, NSC 49142, thyme camphor, m-thymol, and p-cymen-3-ol

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.768 |

| KEGG | |

| UNII |

|

CompTox Dashboard (<abbr title="<nowiki>U.S. Environmental Protection Agency</nowiki>">EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

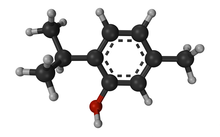

| C10H14O | |

| Molar mass | 150.221 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 0.96 g/cm³ |

| Melting point | 49 to 51 °C (120 to 124 °F; 322 to 324 K) |

| Boiling point | 232 °C (450 °F; 505 K) |

| 0.9 g/L (20 °C)[1] | |

| Pharmacology | |

| QP53AX22 (WHO) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Thymol (còn được gọi là 2-isopropyl-5-methylphenol, IPMP) là một dẫn xuất phenol monoterpenoid tự nhiên của cymene, C10H14O, đồng phân với carvacrol, được tìm thấy trong dầu của cỏ xạ hương và được chiết xuất từ Thymus Vulgaris nhiều loại thực vật khác như một chất tinh thể màu trắng có mùi thơm dễ chịu và tính sát trùng mạnh. Thymol cũng cung cấp hương vị đặc biệt, mạnh mẽ của cỏ xạ hương ẩm thực, cũng được sản xuất từ T. vulgaris.

Hóa học

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]Thymol chỉ tan ít trong nước ở pH trung tính, nhưng nó cực kỳ hòa tan trong rượu và các dung môi hữu cơ khác. Nó cũng hòa tan trong dung dịch nước kiềm mạnh do sự khử hóa của phenol.

Thymol có chiết suất 1,5208 [2] và số mũ phân ly thực nghiệm (pKa) là 1059±010.[3] Thymol hấp thụ bức xạ UV tối đa ở mức 274 bước sóng.[4]

Tổng hợp hóa học

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]Các khu vực thiếu nguồn thymol tự nhiên thu được hợp chất thông qua tổng hợp.[5] Thymol được sản xuất từ <i id="mwLw">m</i>-cresol và propene trong pha khí:[6]

- C7H8O + C3H6 ⇌ C10H14O

Lịch sử

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]Các loài ong dưỡng Monarda fistulosa và Monarda didyma, hoa dại Bắc Mỹ, là nguồn tự nhiên của thymol. Người Mỹ bản địa Blackfoot đã nhận ra hành động sát trùng mạnh mẽ của những cây này và sử dụng thuốc đắp lên cây để trị nhiễm trùng da và vết thương nhỏ. Một tisane làm từ chúng cũng được sử dụng để điều trị nhiễm trùng miệng và cổ họng do sâu răng và viêm nướu.[7]

Thymol lần đầu tiên được phân lập bởi nhà hóa học người Đức Caspar Neumann vào năm 1719.[8] Năm 1853, nhà hóa học người Pháp A. Lallemand đã đặt tên cho thymol và xác định công thức thực nghiệm của nó.[9] Thymol lần đầu tiên được tổng hợp bởi nhà hóa học người Thụy Điển Oskar Widman vào năm 1882.[10]

Nghiên cứu

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]Một nghiên cứu in vitro cho thấy thymol và carvacrol có hiệu quả cao trong việc giảm nồng độ ức chế tối thiểu của một số loại kháng sinh chống lại mầm bệnh và vi khuẩn gây hư hỏng thực phẩm như Salmonella typhimurium SGI 1 và Streptococcus pyogenes ermB.[11] Các nghiên cứu in vitro đã tìm thấy thymol hữu ích như một chất chống nấm chống lại hư hỏng thực phẩm và viêm vú bò.[12] Thymol chứng minh tác dụng sau kháng khuẩn in vitro đối với các chủng xét nghiệm E. coli và P. aeruginosa (gram âm), và S. aureus và B. cereus (gram dương).[13] Hoạt động kháng khuẩn này được gây ra bằng cách ức chế sự tăng trưởng và sản xuất sữa, và bằng cách giảm sự hấp thu glucose của tế bào.[14]

Tinh dầu húng tây rất hữu ích trong việc bảo quản thực phẩm. Các đặc tính kháng khuẩn của thymol, một phần chính của tinh dầu húng tây, cũng như các thành phần khác, một phần liên quan đến đặc tính lipophilic của chúng, dẫn đến sự tích tụ trong màng vi khuẩn và các sự kiện liên quan đến màng, như sự suy giảm năng lượng.[15]

Bản chất kháng nấm của thymol chống lại một số loại nấm gây bệnh cho thực vật là do khả năng thay đổi hình thái của sợi nấm và gây ra các tập hợp sợi nấm, dẫn đến giảm đường kính và màng của sợi nấm.[16]

Danh sách thực vật có chứa thymol

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- Euphrasia rostkoviana [17]

- Monarda didyma[cần dẫn nguồn]

- Monarda fistulosa [18]

- Trạchyspermum ammi

- Origanum compactum [19]

- Origanum dictamnus [20]

- Origanum onites [21][22]

- Origanum Vulgare [23][24]

- Thymus glandulosus [19]

- Thymus hyemalis [25]

- Thymus vulgaris [25][26]

- Thymus zygis [27]

- Symja thymbra

Tác động độc chất và môi trường

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]Năm 2009, Cơ quan Bảo vệ Môi trường Hoa Kỳ (EPA) đã xem xét tài liệu nghiên cứu về độc tính và tác động môi trường của thymol và kết luận rằng "thymol có độc tính tiềm tàng tối thiểu và có nguy cơ tối thiểu".[28]

Phân hủy môi trường và sử dụng làm thuốc trừ sâu

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]Các nghiên cứu đã chỉ ra rằng hydrocarbon monoterpen và thymol đặc biệt suy giảm nhanh chóng (DT50 16 ngày trong nước, 5 ngày trong đất [29]) trong môi trường và do đó, rủi ro thấp do sự phân tán nhanh và dư lượng ràng buộc thấp,[29] hỗ trợ việc sử dụng thymol như một tác nhân thuốc trừ sâu cung cấp một sự thay thế an toàn cho các loại thuốc trừ sâu hóa học dai dẳng khác có thể được phân tán trong dòng chảy và gây ra ô nhiễm tiếp theo.

Tình trạng bổ sung

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- Dược điển Anh [30]

- Dược điển Nhật Bản [31]

Xem thêm

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- Thymoquinone

- Nigella sativa

- Hinokitiol

- Bromothymol

Ghi chú và tài liệu tham khảo

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- ^ "Thymol". PubChem. Truy cập 1 April 2016.

- ^ Mndzhoyan, A. L. (1940). “Thymol from Thymus kotschyanus”. Sbornik Trudov Armyanskogo Filial. Akad. Nauk. 1940: 25–28.

- ^ CAS Registry: Data obtained from SciFinder[cần chú thích đầy đủ]

- ^ Norwitz, G.; Nataro, N.; Keliher, P. N. (1986). “Study of the Steam Distillation of Phenolic Compounds Using Ultraviolent Spectrometry”. Anal. Chem. 58 (639–640): 641. doi:10.1021/ac00294a034.

- ^ Mukhopadhyay, Asim Kumar (2004). Industrial Chemical Cresols and Downstream Derivatives. New York: CRC Press. tr. 99–100. ISBN 9780203997413.

- ^ Stroh, R.; Sydel, R.; Hahn, W. (1963). Foerst, Wilhelm (biên tập). Newer Methods of Preparative Organic Chemistry, Volume 2 (ấn bản thứ 1). New York: Academic Press. tr. 344. ISBN 9780323150422.

- ^ Tilford, Gregory L. (1997). Edible and Medicinal Plants of the West. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87842-359-0.

- ^ Neuman, Carolo (1724). “De Camphora”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 33 (389): 321–332. doi:10.1098/rstl.1724.0061.[liên kết hỏng] On page 324, Neumann mentions that in 1719 (MDCCXIX) he distilled some essential oils from various herbs. On page 326, he mentions that during the course of these experiments, he obtained a crystalline substance from thyme oil, which he called "Camphora Thymi" (camphor of thyme). (Neumann gave the name "camphor" not only to the specific substance that today is called camphor, but to any crystalline substance that precipitated from a volatile, fragrant oil from some plant.)

- ^ Lallemand, A. (1853). “Sur la composition de l'huile essentielle de thym” [On the composition of the essential oil of thyme]. Comptes Rendus (bằng tiếng Pháp). 37: 498–500.

- ^ Widmann, Oskar (1882). “Ueber eine Synthese von Thymol aus Cuminol” [On a synthesis of thymol from cuminol]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (bằng tiếng Đức). 15: 166–172. doi:10.1002/cber.18820150139.

- ^ Palaniappan, Kavitha; Holley, Richard A. (2010). “Use of natural antimicrobials to increase antibiotic susceptibility of drug resistant bacteria”. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 140 (2–3): 164–168. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.04.001. PMID 20457472..

- ^ Nieto, G (2017). “Biological Activities of Three Essential Oils of the Lamiaceae Family”. Medicines. 4 (3): 63. doi:10.3390/medicines4030063. PMC 5622398. PMID 28930277.

- ^ Zarrini, G; Bahari-Delgosha, Z.; Mollazadeh-Moghaddam, K; Shahverdi, A. R. (2010). “Post-antibacterial effect of thymol”. Pharmaceutical Biology. 48 (6): 633–636. doi:10.3109/13880200903229098. PMID 20645735.

- ^ Evans, J.; Martin, J. D. (2000). “Effects of thymol on ruminal microorganisms”. Curr. Microbiol. 41 (5): 336–340. doi:10.1007/s002840010145. PMID 11014870.

- ^ Nychas G.J.E. In: Natural Antimicrobials from Plants. Gould G.W., editor. Blackie Academic Professional; London, UK: 1995. pp. 58–59. New Methods of Food Preservation.

- ^ Numpaque, M. A.; Oviedo, L. A.; Gil, J. H.; García, C. M.; Durango, D. L. (2011). “Thymol and carvacrol: biotransformation and antifungal activity against the plant pathogenic fungi Colletotrichum acutatum and Botryodiplodia theobromae”. Trop. Plant Pathol. 36: 3–13. doi:10.1590/S1982-56762011000100001.

- ^ Novy, P.; Davidova, H.; Serrano Rojero, C. S.; Rondevaldova, J.; Pulkrabek, J.; Kokoska, L. (2015). “Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Euphrasia rostkoviana Hayne Essential Oil”. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015: 1–5. doi:10.1155/2015/734101. PMC 4427012. PMID 26000025.

- ^ Zamureenko, V. A.; Klyuev, N. A.; Bocharov, B. V.; Kabanov, V. S.; Zakharov, A. M. (1989). “An investigation of the component composition of the essential oil of Monarda fistulosa”. Chemistry of Natural Compounds. 25 (5): 549–551. doi:10.1007/BF00598073. ISSN 1573-8388.

- ^ a b Bouchra, Chebli; Achouri, Mohamed; Idrissi Hassani, L. M.; Hmamouchi, Mohamed (2003). “Chemical composition and antifungal activity of essential oils of seven Moroccan Labiatae against Botrytis cinerea Pers: Fr”. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 89 (1): 165–169. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00275-7. PMID 14522450.

- ^ Liolios, C. C.; Gortzi, O.; Lalas, S.; Tsaknis, J.; Chinou, I. (2009). “Liposomal incorporation of carvacrol and thymol isolated from the essential oil of Origanum dictamnus L. and in vitro antimicrobial activity”. Food Chemistry. 112 (1): 77–83. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.05.060.

- ^ Ozkan, Gulcan; Baydar, H.; Erbas, S. (2009). “The influence of harvest time on essential oil composition, phenolic constituents and antioxidant properties of Turkish oregano (Origanum onites L.)”. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 90 (2): 205–209. doi:10.1002/jsfa.3788. PMID 20355032.

- ^ Lagouri, Vasiliki; Blekas, George; Tsimidou, Maria; Kokkini, Stella; Boskou, Dimitrios (1993). “Composition and antioxidant activity of essential oils from Oregano plants grown wild in Greece”. Zeitschrift für Lebensmittel-Untersuchung und -Forschung A. 197 (1): 1431–4630. doi:10.1007/BF01202694.

- ^ Kanias, G. D.; Souleles, C.; Loukis, A.; Philotheou-Panou, E. (1998). “Trace elements and essential oil composition in chemotypes of the aromatic plant Origanum vulgare”. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. 227 (1–2): 23–31. doi:10.1007/BF02386426.

- ^ Figiel, Adam; Szumny, Antoni; Gutiérrez Ortíz, Antonio; Carbonell Barrachina, Ángel A. (2010). “Composition of oregano essential oil (Origanum vulgare) as affected by drying method”. Journal of Food Engineering. 98 (2): 240–247. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2010.01.002.

- ^ a b Goodner, K.L.; Mahattanatawee, K.; Plotto, A.; Sotomayor, J.; Jordán, M. (2006). “Aromatic profiles of Thymus hyemalis and Spanish T. vulgaris essential oils by GC–MS/GC–O”. Industrial Crops and Products. 24 (3): 264–268. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2006.06.006.

- ^ Lee, Seung-Joo; Umano, Katumi; Shibamoto, Takayuki; Lee, Kwang-Geun (2005). “Identification of volatile components in basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) and thyme leaves (Thymus vulgaris L.) and their antioxidant properties”. Food Chemistry. 91 (1): 131–137. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.05.056.

- ^ Moldão Martins, M.; Palavra, A.; Beirão da Costa, M. L.; Bernardo Gil, M. G. (2000). “Supercritical CO2 extraction of Thymus zygis L. subsp. sylvestris aroma”. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids. 18 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1016/S0896-8446(00)00047-4.

- ^ 74 FR 12613

- ^ a b Hu, D.; Coats, J. (2008). “Evaluation of the environmental fate of thymol and phenethyl propionate in the laboratory”. Pest Manag. Sci. 64 (7): 775–779. doi:10.1002/ps.1555. PMID 18381775.

- ^ The British Pharmacopoeia Secretariat (2009). “Index, BP 2009” (PDF). Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 11 tháng 4 năm 2009. Truy cập ngày 5 tháng 7 năm 2009.

- ^ “Japanese Pharmacopoeia” (PDF). Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 22 tháng 7 năm 2011. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 4 năm 2010.

Liên kết ngoài

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]![]() Tư liệu liên quan tới Thymol tại Wikimedia Commons

Tư liệu liên quan tới Thymol tại Wikimedia Commons