Khác biệt giữa bản sửa đổi của “Methamphetamin”

Không có tóm lược sửa đổi |

Không có tóm lược sửa đổi |

||

| Dòng 142: | Dòng 142: | ||

Methamphetamin liên kết và kích hoạt cả hai dưới lớp (subtype) của [[receptor sigma]], [[Thụ thể Sigma-1|σ<sub>1</sub>]] và [[Thụ thể Sigma-2|σ<sub>2</sub>]], với ái lực được tính bằng micromol. <ref name="Sigma">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Kaushal N, Matsumoto RR |date=March 2011 |title=Role of sigma receptors in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity |journal=Curr Neuropharmacol |volume=9 |issue=1 |pages=54–57 |doi=10.2174/157015911795016930 |pmc=3137201 |pmid=21886562 |quote=σ Receptors seem to play an important role in many of the effects of METH. They are present in the organs that mediate the actions of METH (e.g. brain, heart, lungs) [5]. In the brain, METH acts primarily on the dopaminergic system to cause acute locomotor stimulant, subchronic sensitized, and neurotoxic effects. σ Receptors are present on dopaminergic neurons and their activation stimulates dopamine synthesis and release [11–13]. σ-2 Receptors modulate DAT and the release of dopamine via protein kinase C (PKC) and Ca2+-calmodulin systems [14].<br>σ-1 Receptor antisense and antagonists have been shown to block the acute locomotor stimulant effects of METH [4]. Repeated administration or self administration of METH has been shown to upregulate σ-1 receptor protein and mRNA in various brain regions including the substantia nigra, frontal cortex, cerebellum, midbrain, and hippocampus [15, 16]. Additionally, σ receptor antagonists ... prevent the development of behavioral sensitization to METH [17, 18]. ...<br /> σ Receptor agonists have been shown to facilitate dopamine release, through both σ-1 and σ-2 receptors [11–14].}}</ref> <ref name="SigmaB">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Rodvelt KR, Miller DK |date=September 2010 |title=Could sigma receptor ligands be a treatment for methamphetamine addiction? |journal=Curr Drug Abuse Rev |volume=3 |issue=3 |pages=156–162 |doi=10.2174/1874473711003030156 |pmid=21054260}}</ref> Kích hoạt receptor sigma có thể tăng cường độc tính thần kinh do methamphetamin gây ra, bằng cách tạo điều kiện diễn biến tình trạng [[tăng thân nhiệt]], tăng tổng hợp và giải phóng dopamin, ảnh hưởng đến các bước hoạt hóa dưới góc độ vi mô và điều chỉnh "dòng thác tính hiệu" của quá trình [[chết tế bào theo chương trình]], hình thành các [[loài oxy phản ứng]] (reactive oxygen species, ROS). <ref name="Sigma" /> <ref name="SigmaB" /> |

Methamphetamin liên kết và kích hoạt cả hai dưới lớp (subtype) của [[receptor sigma]], [[Thụ thể Sigma-1|σ<sub>1</sub>]] và [[Thụ thể Sigma-2|σ<sub>2</sub>]], với ái lực được tính bằng micromol. <ref name="Sigma">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Kaushal N, Matsumoto RR |date=March 2011 |title=Role of sigma receptors in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity |journal=Curr Neuropharmacol |volume=9 |issue=1 |pages=54–57 |doi=10.2174/157015911795016930 |pmc=3137201 |pmid=21886562 |quote=σ Receptors seem to play an important role in many of the effects of METH. They are present in the organs that mediate the actions of METH (e.g. brain, heart, lungs) [5]. In the brain, METH acts primarily on the dopaminergic system to cause acute locomotor stimulant, subchronic sensitized, and neurotoxic effects. σ Receptors are present on dopaminergic neurons and their activation stimulates dopamine synthesis and release [11–13]. σ-2 Receptors modulate DAT and the release of dopamine via protein kinase C (PKC) and Ca2+-calmodulin systems [14].<br>σ-1 Receptor antisense and antagonists have been shown to block the acute locomotor stimulant effects of METH [4]. Repeated administration or self administration of METH has been shown to upregulate σ-1 receptor protein and mRNA in various brain regions including the substantia nigra, frontal cortex, cerebellum, midbrain, and hippocampus [15, 16]. Additionally, σ receptor antagonists ... prevent the development of behavioral sensitization to METH [17, 18]. ...<br /> σ Receptor agonists have been shown to facilitate dopamine release, through both σ-1 and σ-2 receptors [11–14].}}</ref> <ref name="SigmaB">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Rodvelt KR, Miller DK |date=September 2010 |title=Could sigma receptor ligands be a treatment for methamphetamine addiction? |journal=Curr Drug Abuse Rev |volume=3 |issue=3 |pages=156–162 |doi=10.2174/1874473711003030156 |pmid=21054260}}</ref> Kích hoạt receptor sigma có thể tăng cường độc tính thần kinh do methamphetamin gây ra, bằng cách tạo điều kiện diễn biến tình trạng [[tăng thân nhiệt]], tăng tổng hợp và giải phóng dopamin, ảnh hưởng đến các bước hoạt hóa dưới góc độ vi mô và điều chỉnh "dòng thác tính hiệu" của quá trình [[chết tế bào theo chương trình]], hình thành các [[loài oxy phản ứng]] (reactive oxygen species, ROS). <ref name="Sigma" /> <ref name="SigmaB" /> |

||

=== Nghiện === |

|||

{{Thuật ngữ nghiện}}{{Nghiện chất kích thần}} |

|||

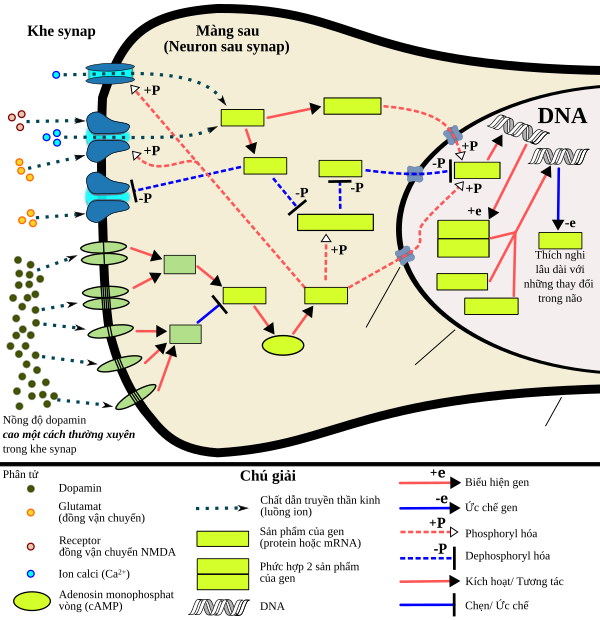

Các mô hình nghiên cứu về nghiện khi sử dụng ma túy lâu ngày gây ra những thay đổi trong [[biểu hiện gen]] ở một số vùng của não, đặc biệt là [[nhân cạp]] (''nucleus accumbens''), phát sinh thông qua cơ chế [[phiên mã]] và [[di truyền học biểu sinh]].<ref name="Nestler3">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Robison AJ, Nestler EJ |date=November 2011 |title=Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction |journal=Nature Reviews Neuroscience |volume=12 |issue=11 |pages=623–637 |doi=10.1038/nrn3111 |pmc=3272277 |pmid=21989194 |quote=ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure<sup>14,22–24</sup>. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption<sup>14,26–30</sup>. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states. ... ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity.}}</ref><ref name="Nestler, Hyman, and Malenka 22">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ |date=July 2006 |title=Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory |url=https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fc1e/144037cd3c08aaf32d0a92b8c55a6ae451a5.pdf |journal=Annual Review of Neuroscience |volume=29 |pages=565–598 |doi=10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009 |pmid=16776597 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180919115435/https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fc1e/144037cd3c08aaf32d0a92b8c55a6ae451a5.pdf |archive-date=2018-09-19}}</ref><ref name="Addiction genetics">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Steiner H, Van Waes V |date=January 2013 |title=Addiction-related gene regulation: risks of exposure to cognitive enhancers vs. other psychostimulants |journal=Progress in Neurobiology |volume=100 |pages=60–80 |doi=10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.10.001 |pmc=3525776 |pmid=23085425}}</ref> Các [[yếu tố phiên mã]] quan trọng nhất{{#tag:ref|Yếu tố phiên mã là các protein làm tăng hoặc giảm [[biểu hiện gen]] cụ thể.<ref name="NHM-Transcription factor">{{chú thích sách |vauthors=Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE |veditors=Sydor A, Brown RY | title = Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience | year = 2009 | publisher = McGraw-Hill Medical | location = New York, USA | isbn = 9780071481274 | page = 94 | edition = 2nd | chapter = Chapter 4: Signal Transduction in the Brain | quote= <!-- All living cells depend on the regulation of gene expression by extracellular signals for their development, homeostasis, and adaptation to the environment. Indeed, many signal transduction pathways function primarily to modify transcription factors that alter the expression of specific genes. Thus, neurotransmitters, growth factors, and drugs change patterns of gene expression in cells and in turn affect many aspects of nervous system functioning, including the formation of long-term memories. Many drugs that require prolonged administration, such as antidepressants and antipsychotics, trigger changes in gene expression that are thought to be therapeutic adaptations to the initial action of the drug. -->}}</ref>|group="chú thích"}} tạo ra những thay đổi này là ''Delta FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B'' ([[ΔFosB]]), ''[[Cyclic adenosine monophosphate|cAMP]]'' ''response element binding protein'' ([[Protein liên kết phần tử phản ứng CAMP|CREB]], tạm dịch: ''protein gắn yếu tố đáp ứng cAMP'') và ''nuclear factor-kappa B'' ([[NF-κB]], tạm dịch: ''Yếu tố hạt nhân tăng cường chuỗi nhẹ kappa của các tế bào B hoạt động'').<ref name="Nestler3" />{{#tag:ref|Thuật ngữ này lấy từ nguồn:<ref>{{Chú thích tạp chí|last=Huyền|first=Đỗ Thị Thanh|last2=Quyên|first2=Phạm Thị|last3=Vân|first3=Nguyễn Thị Hồng|last4=Huy|first4=Nguyễn Quang|date=2021-03-10|title=BIỂU HIỆN VÀ TINH SẠCH NHÂN TỐ PHIÊN MÃ NF- κB P65 CỦA NGƯỜI SỬ DỤNG TẾ BÀO VẬT CHỦ E. coli ĐỊNH HƯỚNG ỨNG DỤNG SÀNG LỌC CHẤT ỨC CHẾ UNG THƯ|url=https://tapchiyhocvietnam.vn/index.php/vmj/article/view/54|journal=Tạp chí Y học Việt Nam|language=vi|volume=498|issue=1|doi=10.51298/vmj.v498i1.54|issn=1859-1868}}</ref>|group="chú thích"}} ΔFosB là cơ chế phân tử sinh học quan trọng nhất trong chứng nghiện vì gen ΔFosB biểu hiện quá mức (tức là mức độ biểu hiện gen cao bất thường khi tạo ra [[kiểu hình]]) trong các neuron gai trung gian (''medium spiny neurons'') loại D1 trong [[nhân cạp]] là điều kiện [[cần và đủ]]{{#tag:ref|Nói một cách đơn giản, mối quan hệ ''cần và đủ'' này có nghĩa là sự biểu hiện quá mức của ΔFosB trong nhân cạo và sự thích nghi về góc độ hành vi và góc độ thần kinh liên quan đến nghiện luôn xảy ra cùng nhau và không bao giờ xảy ra đơn lẻ.|group="chú thích"}} để có những thích ứng liên quan đến thần kinh và những sự điều chỉnh liên quan đến hành vi nghiện (ví dụ: tự tiêm chất gây nghiện theo chiều hướng tăng dần về liều).<ref name="What the ΔFosB?2">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |last=Ruffle JK |date=November 2014 |title=Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about? |journal=The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse |volume=40 |issue=6 |pages=428–437 |doi=10.3109/00952990.2014.933840 |pmid=25083822 |quote=ΔFosB is an essential transcription factor implicated in the molecular and behavioral pathways of addiction following repeated drug exposure.}}</ref><ref name="Nestler2">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Robison AJ, Nestler EJ |date=November 2011 |title=Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction |journal=Nature Reviews Neuroscience |volume=12 |issue=11 |pages=623–637 |doi=10.1038/nrn3111 |pmc=3272277 |pmid=21989194 |quote=ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure<sup>14,22–24</sup>. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption<sup>14,26–30</sup>. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states. ... ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity.}}</ref> Một khi ΔFosB được biểu hiện quá mức, ΔFosB gây ra trạng thái nghiện ngày càng nghiêm trọng hơn do chính những thích ứng liên quan đến thần kinh đó lại tiếp tục làm gia tăng hơn nữa sự biểu hiện quá mức của ΔFosB.<ref name="What the ΔFosB?2" /> Cơ chế này có liên quan đến nghiện [[Chứng nghiện rượu|rượu]], [[cannabinoid]], [[cocain]], [[methylphenidat]], [[nicotin]], [[Thuốc giảm đau nhóm opioid|opioid]], [[phencyclidine]], [[propofol]] và [[Amphetamine thay thế|amphetamin thay thế]], v..v.{{#tag:ref|<ref name="What the ΔFosB?" /><!--Preceding review covers ΔFosB in propofol addiction--><ref name="Natural and drug addictions" /><ref name="Nestler" /><ref name="Alcoholism ΔFosB">{{chú thích web | title=Alcoholism – Homo sapiens (human) | url=http://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa05034+2354 | website=KEGG Pathway | access-date=31 October 2014 | author=Kanehisa Laboratories | date=29 October 2014}}</ref><ref name="MPH ΔFosB">{{chú thích tạp chí | vauthors = Kim Y, Teylan MA, Baron M, Sands A, Nairn AC, Greengard P | title = Methylphenidate-induced dendritic spine formation and DeltaFosB expression in nucleus accumbens | journal =Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences| volume = 106 | issue = 8 | pages = 2915–2920 | date = February 2009 | pmid = 19202072 | pmc = 2650365 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.0813179106 | quote = <!--Despite decades of clinical use of methylphenidate for ADHD, concerns have been raised that long-term treatment of children with this medication may result in subsequent drug abuse and addiction. However, meta analysis of available data suggests that treatment of ADHD with stimulant drugs may have a significant protective effect, reducing the risk for addictive substance use (36, 37). Studies with juvenile rats have also indicated that repeated exposure to methylphenidate does not necessarily lead to enhanced drug-seeking behavior in adulthood (38). However, the recent increase of methylphenidate use as a cognitive enhancer by the general public has again raised concerns because of its potential for abuse and addiction (3, 6–10). Thus, although oral administration of clinical doses of methylphenidate is not associated with euphoria or with abuse problems, nontherapeutic use of high doses or i.v. administration may lead to addiction (39, 40).--> | bibcode = 2009PNAS..106.2915K| doi-access = free }}</ref>|group="cụm nguồn"}} |

|||

[[ΔJunD]], một yếu tố phiên mã và [[EHMT2|G9a]], một enzym [[histone methyltransferase]], đều có tác dụng chống lại chức năng của ΔFosB và ức chế sự gia tăng biểu hiện gen của ΔFosB.<ref name="Nestler4">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Robison AJ, Nestler EJ |date=November 2011 |title=Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction |journal=Nature Reviews Neuroscience |volume=12 |issue=11 |pages=623–637 |doi=10.1038/nrn3111 |pmc=3272277 |pmid=21989194 |quote=ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure<sup>14,22–24</sup>. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption<sup>14,26–30</sup>. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states. ... ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity.}}</ref><ref name="Nestler 2014 epigenetics">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Nestler EJ |date=January 2014 |title=Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction |journal=Neuropharmacology |volume=76 Pt B |pages=259–268 |doi=10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.004 |pmc=3766384 |pmid=23643695 |quote=<!-- Short-term increases in histone acetylation generally promote behavioral responses to the drugs, while sustained increases oppose cocaine's effects, based on the actions of systemic or intra-NAc administration of HDAC inhibitors. ... Genetic or pharmacological blockade of G9a in the NAc potentiates behavioral responses to cocaine and opiates, whereas increasing G9a function exerts the opposite effect (Maze et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2012a). Such drug-induced downregulation of G9a and H3K9me2 also sensitizes animals to the deleterious effects of subsequent chronic stress (Covington et al., 2011). Downregulation of G9a increases the dendritic arborization of NAc neurons, and is associated with increased expression of numerous proteins implicated in synaptic function, which directly connects altered G9a/H3K9me2 in the synaptic plasticity associated with addiction (Maze et al., 2010).<br>G9a appears to be a critical control point for epigenetic regulation in NAc, as we know it functions in two negative feedback loops. It opposes the induction of ΔFosB, a long-lasting transcription factor important for drug addiction (Robison and Nestler, 2011), while ΔFosB in turn suppresses G9a expression (Maze et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2012a). ... Also, G9a is induced in NAc upon prolonged HDAC inhibition, which explains the paradoxical attenuation of cocaine's behavioral effects seen under these conditions, as noted above (Kennedy et al., 2013). GABAA receptor subunit genes are among those that are controlled by this feedback loop. Thus, chronic cocaine, or prolonged HDAC inhibition, induces several GABAA receptor subunits in NAc, which is associated with increased frequency of inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs). In striking contrast, combined exposure to cocaine and HDAC inhibition, which triggers the induction of G9a and increased global levels of H3K9me2, leads to blockade of GABAA receptor and IPSC regulation. -->}}</ref> ΔJunD biểu hiện quá mức trong nhân cạp, phối hợp với [[vector virus]] (''viral vector'') có thể ngăn chặn hoàn toàn nhưng biến đổi liên quan đến thần kinh và hành vi được thấy trong lạm dụng chất lâu ngày (tức là những thay đổi qua trung gian là gen ΔFosB).<ref name="Nestler4" /> Tương tự, hiện tượng biểu hiện quá mức gen G9a tại nhân cạp làm tăng rõ rệt quá trình [[Methyl hóa|dimethyl hóa]] nhóm lysin dư thừa tại vị trí số 9 trên protein histon H3 (tiếng Anh: ''histone 3 lysine residue 9 dimethylation'' - [[H3K9me2]], histon H3 là một protein đóng gói DNA) và ức chế sự cảm ứng của [[tính dẻo hành vi]] (''behavioral plasticity'') và [[khả biến thần kinh]] (''neuroplasticity'') qua trung gian ΔFosB do sử dụng thuốc dài ngày.{{#tag:ref|<ref name="Nestler" /><ref name="G9a reverses ΔFosB plasticity">{{chú thích tạp chí | vauthors = Biliński P, Wojtyła A, Kapka-Skrzypczak L, Chwedorowicz R, Cyranka M, Studziński T | title = Epigenetic regulation in drug addiction | journal = Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine | volume = 19 | issue = 3 | pages = 491–496 | year = 2012 | pmid = 23020045 | url = http://www.aaem.pl/Epigenetic-regulation-in-drug-addiction,71809,0,2.html }}</ref><ref name="HDACi-induced G9a+H3K9me2 primary source">{{chú thích tạp chí | vauthors = Kennedy PJ, Feng J, Robison AJ, Maze I, Badimon A, Mouzon E, Chaudhury D, Damez-Werno DM, Haggarty SJ, Han MH, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Nestler EJ | title = Class I HDAC inhibition blocks cocaine-induced plasticity by targeted changes in histone methylation | journal = Nature Neuroscience | volume = 16 | issue = 4 | pages = 434–440 | date = April 2013 | pmid = 23475113 | pmc = 3609040 | doi = 10.1038/nn.3354 }}</ref><ref name="A feat of epigenetic engineering">{{chú thích tạp chí | vauthors = Whalley K | title = Psychiatric disorders: a feat of epigenetic engineering | journal = Nature Reviews. Neuroscience | volume = 15 | issue = 12 | pages = 768–769 | date = December 2014 | pmid = 25409693 | doi = 10.1038/nrn3869 | s2cid = 11513288 }}</ref>|group="cụm nguồn"}} Sự ức chế trên xảy ra thông qua:<ref name="Nestler4" /><ref name="Nestler 2014 epigenetics" /> |

|||

# Ức chế qua trung gian H3K9me2 (''H3K9me2-mediated repression'') đối với các [[yếu tố phiên mã]] gen ΔFosB |

|||

# Ức chế qua trung gian H3K9me2 đối với các mục tiêu thúc đẩy sự phiên mã của gen ΔFosB (ví dụ: enzyme cyclin-dependent kinase 5, [[CDK5]]). |

|||

ΔFosB đóng vai trò quan trọng trong việc điều chỉnh các đáp ứng hành vi đối với [[Nghiện hành vi|hành vi nghiện]], chẳng hạn như thưởng thức bữa ăn ngon, tình dục và tập thể dục.<ref name="Natural and drug addictions2">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |author=Olsen CM |date=December 2011 |title=Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions |journal=Neuropharmacology |volume=61 |issue=7 |pages=1109–1122 |doi=10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010 |pmc=3139704 |pmid=21459101 |quote=Similar to environmental enrichment, studies have found that exercise reduces self-administration and relapse to drugs of abuse (Cosgrove et al., 2002; Zlebnik et al., 2010). There is also some evidence that these preclinical findings translate to human populations, as exercise reduces withdrawal symptoms and relapse in abstinent smokers (Daniel et al., 2006; Prochaska et al., 2008), and one drug recovery program has seen success in participants that train for and compete in a marathon as part of the program (Butler, 2005). ... In humans, the role of dopamine signaling in incentive-sensitization processes has recently been highlighted by the observation of a dopamine dysregulation syndrome in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs. This syndrome is characterized by a medication-induced increase in (or compulsive) engagement in non-drug rewards such as gambling, shopping, or sex (Evans et al., 2006; Aiken, 2007; Lader, 2008).}}</ref><ref name="Nestler4" /><ref name="ΔFosB reward">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Blum K, Werner T, Carnes S, Carnes P, Bowirrat A, Giordano J, Oscar-Berman M, Gold M |date=March 2012 |title=Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll: hypothesizing common mesolimbic activation as a function of reward gene polymorphisms |journal=Journal of Psychoactive Drugs |volume=44 |issue=1 |pages=38–55 |doi=10.1080/02791072.2012.662112 |pmc=4040958 |pmid=22641964 |quote=It has been found that deltaFosB gene in the NAc is critical for reinforcing effects of sexual reward. Pitchers and colleagues (2010) reported that sexual experience was shown to cause DeltaFosB accumulation in several limbic brain regions including the NAc, medial pre-frontal cortex, VTA, caudate, and putamen, but not the medial preoptic nucleus. ... these findings support a critical role for DeltaFosB expression in the NAc in the reinforcing effects of sexual behavior and sexual experience-induced facilitation of sexual performance. ... both drug addiction and sexual addiction represent pathological forms of neuroplasticity along with the emergence of aberrant behaviors involving a cascade of neurochemical changes mainly in the brain's rewarding circuitry.}}</ref> Vì những "phần thưởng" (tưởng thưởng) nêu trên và thuốc gây nghiện đều gây ra [[biểu hiện gen]] của gen ΔFosB (tức là khiến não sản xuất ra nhiều hơn), việc lâu dài tiếp nhận các "phần thưởng" nêu trên cũng có thể dẫn đến tình trạng nghiện bệnh lý.<ref name="Natural and drug addictions2" /><ref name="Nestler4" /> Do đó, ΔFosB là yếu tố quan trọng nhất liên quan đến cả nghiện amphetamin và [[nghiện tình dục]] do amphetamin, là những hành vi tình dục cưỡng bức do hoạt động tình dục quá mức và sử dụng amphetamin.<ref name="Natural and drug addictions2" /><ref name="Amph-Sex X-sensitization through D1 signaling">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Pitchers KK, Vialou V, Nestler EJ, Laviolette SR, Lehman MN, Coolen LM |date=February 2013 |title=Natural and drug rewards act on common neural plasticity mechanisms with ΔFosB as a key mediator |journal=The Journal of Neuroscience |volume=33 |issue=8 |pages=3434–3442 |doi=10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4881-12.2013 |pmc=3865508 |pmid=23426671}}</ref><ref name="Amph-Sex X-sensitization through NMDA signaling">{{Chú thích tập san học thuật |vauthors=Beloate LN, Weems PW, Casey GR, Webb IC, Coolen LM |date=February 2016 |title=Nucleus accumbens NMDA receptor activation regulates amphetamine cross-sensitization and deltaFosB expression following sexual experience in male rats |journal=Neuropharmacology |volume=101 |pages=154–164 |doi=10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.023 |pmid=26391065}}</ref> Những chứng nghiện tình dục này có liên quan đến [[hội chứng rối loạn điều hòa dopamin]] xảy ra ở một số bệnh nhân dùng [[Dopaminergic|thuốc dopaminergic]] như là amphetamin hoặc methamphetamin.<ref name="Natural and drug addictions2" /><ref name="ΔFosB reward" /> |

|||

== Quá liều == |

== Quá liều == |

||

Phiên bản lúc 08:41, ngày 19 tháng 10 năm 2023

Một biên tập viên đang sửa phần lớn trang bài viết này trong một thời gian ngắn. Để tránh mâu thuẫn sửa đổi, vui lòng không chỉnh sửa trang khi còn xuất hiện thông báo này. Người đã thêm thông báo này sẽ được hiển thị trong lịch sử trang này. Nếu như trang này chưa được sửa đổi gì trong vài giờ, vui lòng gỡ bỏ bản mẫu. Nếu bạn là người thêm bản mẫu này, hãy nhớ xoá hoặc thay bản mẫu này bằng bản mẫu {{Đang viết}} giữa các phiên sửa đổi. Trang này được sửa đổi lần cuối vào lúc 08:41, 19 tháng 10, 2023 (UTC) (7 tháng trước) — Xem khác biệt hoặc trang này. |

| |||

| |||

| Dữ liệu lâm sàng | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Phát âm | /ˌmɛθæmˈfɛtəmiːn/ (METH-am-FET-ə-meen), /ˌmɛθəmˈfɛtəmiːn/ (METH-əm-FET-ə-meen), /ˌmɛθəmˈfɛtəmən/ (METH-əm-FET-ə-mən)[1] | ||

| Tên thương mại | Desoxyn, Methedrine | ||

| Đồng nghĩa | N-methylamphetamine, N,α-dimethylphenethylamine, desoxyephedrine | ||

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Chuyên khảo | ||

| Giấy phép |

| ||

| Danh mục cho thai kỳ |

| ||

| Mã ATC | |||

| Tình trạng pháp lý | |||

| Tình trạng pháp lý |

| ||

| Dữ liệu dược động học | |||

| Liên kết protein huyết tương | Đa dạng[3] | ||

| Chuyển hóa dược phẩm | CYP2D6[2] and FMO3 | ||

| Chu kỳ bán rã sinh học | 9–12 hours (range 5–30 hours) (irrespective of route) | ||

| Thời gian hoạt động | 8–12 giờ[4] | ||

| Bài tiết | Qua thận | ||

| Các định danh | |||

Tên IUPAC

| |||

| Số đăng ký CAS | |||

| PubChem CID | |||

| IUPHAR/BPS | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| Định danh thành phần duy nhất |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| Phối tử ngân hàng dữ liệu protein | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.882 | ||

| Dữ liệu hóa lý | |||

| Công thức hóa học | C10H15N | ||

| Khối lượng phân tử | 149,24 g·mol−1 | ||

| Mẫu 3D (Jmol) | |||

| Thủ đối tính hóa học | Racemic mixture | ||

| Điểm nóng chảy | 170 °C (338 °F) [5] | ||

| Điểm sôi | 212 °C (414 °F) at 760 mmHg[5] | ||

SMILES

| |||

Định danh hóa học quốc tế

| |||

| (kiểm chứng) | |||

Methamphetamin[chú thích 1] (tên đầy đủ N-methylamphetamin, thường gọi là ma túy đá) là một chất kích thích hệ thần kinh trung ương (CNS) nhóm amphetamin từng được sử dụng không phổ biến như một phương pháp điều trị bổ sung cho rối loạn tăng động giảm chú ý (ADHD), và béo phì, nhưng lại phổ biến được sử dụng như một loại thuốc giải trí tiêu khiển.[11] Methamphetamin được phát hiện vào năm 1893 và tồn tại dưới dạng hai chất đối quang (enantiomer):[chú thích 2] levo-methamphetamin và dextro-methamphetamin. Danh pháp methamphetamin đề cập cho một chất hóa học cụ thể, đó là dạng base liên hợp của amin (free-base) ở dạng amin tinh khiết của với tỷ lệ ngang nhau giữa levo-methamphetamin và dextro-methamphetamin. Methamphetamin hiếm khi được chỉ định vì nguy cơ gây độc thần kinh đối với con người và hành vi lạm dụng giải trí tiêu khiển như một loại thuốc kích dục và thuốc hưng thần (euphoria). Dextroamphetamin kích thích hệ thần kinh trung ương mạnh hơn levomethamphetamin.

Buôn bán và vận chuyển hỗn hợp racemic methamphetamin và dextromethamphetamin đều bị coi là bất hợp pháp .Tỷ lệ sử dụng methamphetamin cao nhất xảy ra ở các khu vực Châu Á và Châu Đại Dương, và ở Hoa Kỳ, methamphetamin được phân loại là chất kiểm soát theo danh mục II. Ở Hoa Kỳ, levomethamphetamin là thuốc không kê đơn, sử dụng làm thuốc thông mũi dạng hít.[chú thích 3] Hầu hết tất cả mọi quốc gia trên thế giới, việc sản xuất, phân phối, mua bán và sở hữu methamphetamin đều phải được kiểm soát hoặc bị cấm, do nó nằm trong danh mục II của hiệp ước Liên hợp quốc về các chất ma túy. Mặc dù dextromethamphetamin có tác dụng mạnh hơn nhưng racemic của methamphetamin thường được sản xuất bất hợp pháp hơn do tổng hợp khá dễ dàng và tiền chất tổng hợp thường sẵn có.

Ở liều thấp, methamphetamin giúp nâng cao tâm trạng (hưng thần), tăng tập trung, chú ý và tạo cảm giác tràn đầy sức sống cho những người mệt mỏi, chán ăn và thúc đẩy giảm cân. Đối với liều cao kéo dài, chất có thể gây ra rối loạn tâm thần, co giật và xuất huyết não. Sử dụng liều cao kéo dài có thể gây rối loạn cảm xúc (rối loạn tâm trạng), rối loạn tâm thần (ví dụ: ảo giác, sảng, hoang tưởng, paranoia) và bạo lực. Đối với giải trí tiêu khiển, methamphetamin có khả năng tăng năng lượng, hưng thần và tăng ham muốn và khả năng tình dục đến một mức độ mà người dùng có thể tham gia vào các hoạt động tình dục liên tục trong vài ngày.[16] Methamphetamin được biết là gây nghiện cao. Khi ngừng sử dụng methamphetamin có thể dẫn đến hội chứng cai nghiện cấp tính (PAWS). Methamphetamin liều cao có khả năng gây ngộ độc các neuron dopaminergic trung não của người. Methamphetamine được chứng minh là có ái lực cao với neuron serotonergic hơn amphetamin.[17][18] Độc tính methamphetamin gây ra những thay đổi bất lợi trong cấu trúc và chức năng của não bộ, chẳng hạn như giảm khối lượng chất xám ở một số vùng trong não, cũng như những thay đổi bất lợi trong các dấu hiệu của sự toàn vẹn trao đổi chất.[19]

Một số tên gọi khác: N-methylamphetamine, desoxyephedrine, Syndrox, Methedrine, và Desoxyn.[6][20][21]

Methamphetamin thuộc nhóm hóa chất dẫn xuất phenethylamin và dẫn xuất amphetamin. Methamphetamin là đồng phân cấu tạo về vị trí nhóm chức của dimethylphenethylamin, có chung công thức hóa học là C

10H

15N.

Ứng dụng

Y học

Tại Hoa Kỳ, methamphetamin hydrochloride, dưới tên thương mại Desoxyn, đã được FDA chấp thuận để kê đơn điều trị bệnh ADHD và béo phì ở người lớn và trẻ nhỏ.[22] [23] Tuy nhiên, FDA cũng chỉ ra rằng công dụng điều trị của methamphetamin còn hạn chế, cần được cân nhắc với những nguy cơ cố hữu liên quan đến việc sử dụng chất.[22] Để tránh độc tính và nguy cơ bị tác dụng phụ, hướng dẫn chẩn đoán và điều trị của FDA khuyến nghị liều methamphetamin ban đầu là 5–10 mg/ngày đối với ADHD ở người lớn và trẻ em trên 6 tuổi và có thể mỗi tuần tăng liều thêm 5 mg, tối đa là 25 mg/ngày cho đến khi đạt được đáp ứng lâm sàng tối ưu; liều hiệu quả thông thường là khoảng 20–25 mg/ngày.[7][22]

Methamphetamine đôi khi được kê đơn off-label (kê đơn không theo hướng dẫn trên nhãn) điều trị chứng ngủ rũ và mất ngủ vô căn. Tại Hoa Kỳ, levomethamphetamin có trong một số sản phẩm thuốc thông mũi không kê đơn.[chú thích 4]

Bởi vì methamphetamin hay bị lạm dụng, nên loại thuốc này được quy định theo Đạo luật về các chất kiểm soát và được liệt kê theo Danh mục II ở Hoa Kỳ.[27] Methamphetamin hydrochloride được phân phối tại Hoa Kỳ bắt buộc phải bao gồm nhãn cảnh báo nguy hiểm về khả năng gây nghiện và lạm dụng sai mục đích để giải trí.[27]

Methamphetamin có hai dược phẩm là Desoxyn và Desoxyn Gradumet. Desoxyn Gradumet không còn được sản xuất nữa vì là dạng thuốc giải phóng tác dụng dài, làm phẳng đường cong tác dụng và kéo dài thời gian tác dụng của thuốc. [28]

Sử dụng để giải trí

Methamphetamin thường phổ biến được sử dụng để giải trí tiêu khiển vì tác dụng gây hưng phấn và kích thích mạnh, cũng như là chất kích dục. [29]

Theo một bộ phim tài liệu của National Geographic TV về methamphetamin, có một kiểu văn hóa được gọi là Sử dụng chất khi quan hệ tình dục (chemsex hay party and play)[30] dựa trên hoạt động tình dục và sử dụng methamphetamin.[29] Những người tham gia tích cực vào kiểu hoạt động tình dục này gần như hoàn toàn là những người đồng tính, họ thường sẽ gặp gỡ nhau qua các trang web hẹn hò trên internet và sau đó quan hệ tình dục.[29] Do có tác dụng kích thích tâm tinh thần và kích dục mạnh và tác dụng ức chế xuất tinh kèm theo việc sử dụng nhiều lần, quá trình quan hệ tình dục ở những lần này đôi khi có thể diễn ra liên tục trong nhiều ngày liền.[29] Sự "tụt dốc" trong tinh thần sau khi sử dụng methamphetamin để quan hệ thường rất nghiêm trọng, người sử dụng meth sẽ bị mắc chứng ngủ quá nhiều.[29] Tệ nạn này thường ở các thành phố lớn ở Hoa Kỳ như San Francisco và New York City.[29][31]

Chống chỉ định

Chống chỉ định methamphetamin ở những người có tiền sử rối loạn sử dụng chất gây nghiện, bệnh tim mạch, dễ bị kích động, dễ lo âu, hoặc ở những bệnh nhân bị xơ cứng động mạch, glôcôm, cường giáp hoặc tăng huyết áp mức độ nặng. [32] FDA khuyến cáo những cá nhân đã từng có phản ứng quá mẫn với các chất kích thích khác trong quá khứ hoặc hiện đang dùng thuốc ức chế monoamine oxidase (MAOIs) không nên dùng methamphetamin. [32] FDA cũng khuyến cáo những người mắc rối loạn lưỡng cực, trầm cảm, tăng huyết áp, các vấn đề về chức năng gan hoặc thận, hưng cảm, loạn thần, hội chứng Raynaud, cơn động kinh, các vấn đề về tuyến giáp, tic hoặc hội chứng Tourette nên theo dõi các triệu chứng của họ khi dùng methamphetamin. [32] Do nguy cơ ảnh hưởng đến chậm phát triển thể chất, FDA khuyên nên theo dõi chiều cao và cân nặng của trẻ em và thanh thiếu niên trong quá trình điều trị. [32]

Tác dụng phụ

Tác dụng lên thể chất

Tác động lên sức khỏe thể chất của methamphetamin bao gồm chán ăn, tăng động, giãn đồng tử, da ửng đỏ, đổ mồ hôi nhiều, khô miệng và nghiến răng (gây nên hiện tượng miệng meth), nhức đầu, rối loạn nhịp tim (thường là nhịp nhanh hoặc nhịp chậm), thở nhanh, tăng huyết áp, tụt huyết áp, tăng thân nhiệt, tiêu chảy, táo bón, mờ mắt, chóng mặt, co giật, tê, run, da khô, mụn trứng cá và người xanh xao. [33][34] Người dùng meth lâu dài có thể bị loét da;[35][36][37] những vết này có thể là do họ "gãi ngứa"[38] vì họ tin rằng có côn trùng nào đó đang bò dưới da.[39] Có nhiều báo các về trường hợp tử vong liên quan đến sốc methamphetamin.[40][41]

Miệng meth

Người sử dụng và người nghiện methamphetamin có thể bị hỏng răng với tốc độ nhanh chóng, tình trạng này nghiêm trọng nhất ở những người sử dụng thuốc qua đường tiêm chích. [42] Theo Hiệp hội Nha khoa Hoa Kỳ, bệnh miệng meth "có thể là do sự kết hợp của những thay đổi tâm lý và sinh lý do thuốc gây ra, dẫn đến chứng khô miệng, không vệ sinh răng miệng trong thời gian dài, và chứng nghiến răng”.[43] [44] Tuy nhiên một số nhà nghiên cứu cho rằng tác dụng hỏng răng của meth bị phóng đại và cách điệu hóa để tạo ra định kiến, định hướng người sử dụng như một sự răn đe, cảnh báo người bắt đầu sử dụng methamphetamin. [45]

Bệnh lây truyền qua đường tình dục

Việc sử dụng meth được phát hiện là có khả năng làm trầm trọng thêm tình trạng quan hệ tình dục không an toàn ở cả bạn tình nhiễm HIV và bạn tình không quen biết.[46] Những phát hiện này cho thấy rằng việc sử dụng methamphetamin và quan hệ tình dục qua đường hậu môn không có phương tiện bảo vệ là những hành vi nguy hiểm, có khả năng tăng nguy cơ lây truyền HIV ở nam giới đồng tính và dị tính luyến ái.[47] Sử dụng methamphetamin cho phép cả hai giới hoạt động tình dục kéo dài liên tục, có thể gây lở loét và trầy xước bộ phận sinh dục cũng như chứng cương đau ở nam giới.[48][49] Methamphetamin cũng có thể gây lở loét và trầy xước trong miệng do nghiến răng, làm tăng nguy cơ lây nhiễm bệnh qua đường tình dục. [48][49]

Bên cạnh việc lây truyền HIV qua đường tình dục, HIV cũng có thể lây giữa những người sử dụng chung kim tiêm. [50] Mức độ dùng chung kim tiêm giữa những người sử dụng methamphetamin cũng tương tự như ở những đối tượng sử dụng ma túy khác.[50]

Tác dụng tâm lý

Các tác động lên tâm lý của methamphetamin bao gồm hưng phấn, bức bối, thay đổi ham muốn tình dục, cảnh giác, e ngại và tập trung, giảm cảm giác mệt mỏi, làm mất ngủ hoặc gây tỉnh táo, tự tin, hòa đồng, dễ nổi cáu, bồn chồn, hoang tưởng và các hành vi lặp đi lặp lại và ám ảnh. [51][52][53] Điểm đặc biệt của methamphetamin và các chất kích thích có liên quan là hoạt động lặp đi lặp lại liên tục không có rõ mục tiêu.[54] Sử dụng methamphetamin cũng có mối tương quan cao với lo âu, trầm cảm, rối loạn tâm thần do amphetamin, tự sát và các hành vi bạo lực.[55] [56]

Độc thần kinh và miễn dịch thần kinh

Methamphetamin gây độc trực tiếp cho neuron (tế bào thần kinh) dopaminergic ở cả động vật thí nghiệm và người.[57][58] Kích thích độc tế bào (excitotoxicity), stress oxy hóa, rối loạn chức năng hệ ubiquitin-proteasome (UPS), nitrat hóa protein, stress mạng lưới nội chất trong tế bào beta (endoplasmic reticulum stress in beta cells), biểu hiện gen p53 và các quá trình khác góp phần gây ra ngộ độc thần kinh.[59][60] [61] Cùng với độc tính thần kinh dopaminergic, việc sử dụng methamphetamin tăng nguy cơ mắc bệnh Parkinson.[62] Ngoài độc tính thần kinh dopaminergic, một tổng quan hệ thống thu thập các bằng chứng ở người chỉ ra rằng sử dụng methamphetamin liều cao cũng có thể gây độc đối với neuron serotonergic. [63] Thân nhiệt cao (nhiệt độ cơ thể cao) được chứng minh là có liên quan đến gia tăng tác dụng gây độc thần kinh của methamphetamin.[64] Việc ngừng sử dụng methamphetamin ở những người phụ thuộc có thể dẫn đến tình trạng hội chứng cai đeo đẳng nhiều tháng. [61]

Các nghiên cứu phim chụp cộng hưởng từ trên người sử dụng methamphetamin cũng đã cho thấy bằng chứng về sự thoái hóa thần kinh hoặc những thay đổi bất lợi về tế bào thần kinh trong cấu trúc và chức năng của não.[65] Đặc biệt, methamphetamin dường như gây nên tình trạng tăng tín hiệu trên T2 và phì đại chất trắng, làm teo hải mã và giảm chất xám ở vỏ não đai, vỏ não viền (limbic cortex) và vỏ não cận viền (paralimbic cortex) ở những người sử dụng methamphetamine để tiêu khiển. Hơn nữa, các bằng chứng cho thấy nồng độ dấu ấn sinh học về tính toàn vẹn và tổng hợp trao đổi chất ở những người sử dụng giải trí diễn biến theo chiều hướng bất lợi, chẳng hạn như nồng độ N-acetylaspartat và creatine thì giảm, còn nồng độ choline và myoinositol tăng cao.[65]

Methamphetamin được chứng minh là kích hoạt TAAR1 trong tế bào tk đệm hình sao ở người và tạo ra AMP vòng (cAMP). [66] Kích hoạt TAAR1 trong tế bào hình sao có thể là một cơ chế giúp methamphetamin làm suy giảm nồng độ EAAT2 (SLC1A2) gắn màng và hoạt động trong các tế bào này. [66]

Methamphetamin liên kết và kích hoạt cả hai dưới lớp (subtype) của receptor sigma, σ1 và σ2, với ái lực được tính bằng micromol. [67] [68] Kích hoạt receptor sigma có thể tăng cường độc tính thần kinh do methamphetamin gây ra, bằng cách tạo điều kiện diễn biến tình trạng tăng thân nhiệt, tăng tổng hợp và giải phóng dopamin, ảnh hưởng đến các bước hoạt hóa dưới góc độ vi mô và điều chỉnh "dòng thác tính hiệu" của quá trình chết tế bào theo chương trình, hình thành các loài oxy phản ứng (reactive oxygen species, ROS). [67] [68]

Nghiện

| Thuật ngữ về chứng nghiện và phụ thuộc[69][70][71][72] | |

|---|---|

| |

Các mô hình nghiên cứu về nghiện khi sử dụng ma túy lâu ngày gây ra những thay đổi trong biểu hiện gen ở một số vùng của não, đặc biệt là nhân cạp (nucleus accumbens), phát sinh thông qua cơ chế phiên mã và di truyền học biểu sinh.[80][81][82] Các yếu tố phiên mã quan trọng nhất[chú thích 5] tạo ra những thay đổi này là Delta FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (ΔFosB), cAMP response element binding protein (CREB, tạm dịch: protein gắn yếu tố đáp ứng cAMP) và nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB, tạm dịch: Yếu tố hạt nhân tăng cường chuỗi nhẹ kappa của các tế bào B hoạt động).[80][chú thích 6] ΔFosB là cơ chế phân tử sinh học quan trọng nhất trong chứng nghiện vì gen ΔFosB biểu hiện quá mức (tức là mức độ biểu hiện gen cao bất thường khi tạo ra kiểu hình) trong các neuron gai trung gian (medium spiny neurons) loại D1 trong nhân cạp là điều kiện cần và đủ[chú thích 7] để có những thích ứng liên quan đến thần kinh và những sự điều chỉnh liên quan đến hành vi nghiện (ví dụ: tự tiêm chất gây nghiện theo chiều hướng tăng dần về liều).[85][78] Một khi ΔFosB được biểu hiện quá mức, ΔFosB gây ra trạng thái nghiện ngày càng nghiêm trọng hơn do chính những thích ứng liên quan đến thần kinh đó lại tiếp tục làm gia tăng hơn nữa sự biểu hiện quá mức của ΔFosB.[85] Cơ chế này có liên quan đến nghiện rượu, cannabinoid, cocain, methylphenidat, nicotin, opioid, phencyclidine, propofol và amphetamin thay thế, v..v.[cụm nguồn 1]

ΔJunD, một yếu tố phiên mã và G9a, một enzym histone methyltransferase, đều có tác dụng chống lại chức năng của ΔFosB và ức chế sự gia tăng biểu hiện gen của ΔFosB.[91][92] ΔJunD biểu hiện quá mức trong nhân cạp, phối hợp với vector virus (viral vector) có thể ngăn chặn hoàn toàn nhưng biến đổi liên quan đến thần kinh và hành vi được thấy trong lạm dụng chất lâu ngày (tức là những thay đổi qua trung gian là gen ΔFosB).[91] Tương tự, hiện tượng biểu hiện quá mức gen G9a tại nhân cạp làm tăng rõ rệt quá trình dimethyl hóa nhóm lysin dư thừa tại vị trí số 9 trên protein histon H3 (tiếng Anh: histone 3 lysine residue 9 dimethylation - H3K9me2, histon H3 là một protein đóng gói DNA) và ức chế sự cảm ứng của tính dẻo hành vi (behavioral plasticity) và khả biến thần kinh (neuroplasticity) qua trung gian ΔFosB do sử dụng thuốc dài ngày.[cụm nguồn 2] Sự ức chế trên xảy ra thông qua:[91][92]

- Ức chế qua trung gian H3K9me2 (H3K9me2-mediated repression) đối với các yếu tố phiên mã gen ΔFosB

- Ức chế qua trung gian H3K9me2 đối với các mục tiêu thúc đẩy sự phiên mã của gen ΔFosB (ví dụ: enzyme cyclin-dependent kinase 5, CDK5).

ΔFosB đóng vai trò quan trọng trong việc điều chỉnh các đáp ứng hành vi đối với hành vi nghiện, chẳng hạn như thưởng thức bữa ăn ngon, tình dục và tập thể dục.[96][91][97] Vì những "phần thưởng" (tưởng thưởng) nêu trên và thuốc gây nghiện đều gây ra biểu hiện gen của gen ΔFosB (tức là khiến não sản xuất ra nhiều hơn), việc lâu dài tiếp nhận các "phần thưởng" nêu trên cũng có thể dẫn đến tình trạng nghiện bệnh lý.[96][91] Do đó, ΔFosB là yếu tố quan trọng nhất liên quan đến cả nghiện amphetamin và nghiện tình dục do amphetamin, là những hành vi tình dục cưỡng bức do hoạt động tình dục quá mức và sử dụng amphetamin.[96][98][99] Những chứng nghiện tình dục này có liên quan đến hội chứng rối loạn điều hòa dopamin xảy ra ở một số bệnh nhân dùng thuốc dopaminergic như là amphetamin hoặc methamphetamin.[96][97]

Quá liều

Quá liều methamphetamin có thể dẫn đến một loạt các triệu chứng.[100][101] Quá liều methamphetamin nhẹ có thể gây ra các triệu chứng như: nhịp tim bất thường, lú lẫn, đi tiểu khó và / hoặc đau, huyết áp cao hoặc thấp, nhiệt độ cơ thể cao, đau cơ, kích động dữ dội, thở gấp, run, tiểu nhiều và không thể đi tiểu.[102][101] Quá liều nặng có thể tạo ra các triệu chứng như bão adrenergic, rối loạn tâm thần methamphetamin, giảm đáng kể hoặc không có nước tiểu, sốc tim, chảy máu trong não, trụy tuần hoàn, nhiệt độ cơ thể cao mức nguy hiểm, tăng áp phổi, suy thận, tê liệt, hội chứng serotonin. Thông thường, trước khi tử vong do ngộ độc methamphetamin người dùng thường có thể có biểu hiện co giật và hôn mê. [100]

Rối loạn tâm thần

Sử dụng methamphetamin có thể dẫn đến rối loạn tâm thần do chất kích thích có thể xuất hiện với nhiều triệu chứng khác nhau (ví dụ: ảo giác, mê sảng và hoang tưởng, hoang tưởng ảo giác thể paranoid).[103] Một đánh giá hợp tác của Cochrane về điều trị chứng rối loạn tâm thần do sử dụng amphetamin, dextroamphetamin và methamphetamin cho biết rằng nhiều người dùng không thể phục hồi hoàn toàn.[104] Đánh giá tương tự khẳng định rằng, dựa trên ít nhất một thử nghiệm, thuốc chống loạn thần có thể giảm nhẹ các triệu chứng của rối loạn tâm thần cấp do amphetamin.

Điều trị cấp cứu

Ngộ độc methamphetamin cấp tính phần lớn được sơ cứu bằng cách dùng than hoạt tính và thuốc an thần. [105] Bài tiểu cưỡng bức bằng axit (ví dụ, với vitamin C ) sẽ làm tăng bài tiết methamphetamin nhưng không được khuyến khích vì có thể làm tăng nguy cơ làm trầm trọng thêm tình trạng, hoặc gây co giật hoặc tiêu cơ vân.[105] Tăng huyết áp có nguy cơ gây xuất huyết nội sọ (tức là chảy máu trong não) và nếu nghiêm trọng, thường được điều trị bằng phentolamine tiêm tĩnh mạch hoặc nitroprusside. [105] Thuốc chống loạn thần như haloperidol rất hữu ích trong điều trị kích động và rối loạn tâm thần do dùng quá liều methamphetamin.

Hoá học

Methamphetamin là một hợp chất chiral với hai chất đối quang, dextromethamphetamin và levomethamphetamin. Muối methamphetamin hydrochloride có điểm nóng chảy từ 170 và 175 °C (338 và 347 °F) và ở nhiệt độ phòng, xuất hiện dưới dạng tinh thể màu trắng hoặc bột kết tinh màu trắng. Cấu trúc tinh thể của methamphetamin hydrochloride có dạng đơn tà với nhóm không gian P21; ở 90 K (−183,2 °C; −297,7 °F), các thông số: a = 7.10 Å, b = 7,29 Å, c = 10,81 Å, và β = 97,29 °. [106]

Lịch sử, và văn hóa

Amphetamin, được phát hiện trước methamphetamin, lần đầu tiên được tổng hợp vào năm 1887 tại Đức bởi nhà hóa học Lazăr Edeleanu, ông đặt tên cho là phenylisopropylamine.[107][108] Ngay sau đó, methamphetamin được tổng hợp từ ephedrine vào năm 1893 bởi nhà hóa học người Nhật Bản Nagai Nagayoshi.[109]

Kể từ năm 1938, methamphetamin được tiếp thị trên quy mô lớn ở Đức dưới dạng thuốc không kê đơn dưới tên thương hiệu Pervitin, được sản xuất bởi công ty dược phẩm Temmler có trụ sở tại Berlin.[110][111] Hợp chất này được sử dụng bởi các lực lượng vũ trang tổng hợp của Đệ tam Đế chế, vì tác dụng kích thích và gây ra sự cảnh giác cao độ kéo dài.[112] Pervitin được quân đội Đức biết đến một cách thông tục với cái tên " Stuka -Tablets" ( Stuka-Tabletten ) và " Herman-Göring -Pills" ( Hermann-Göring-Pillen ), như một ám chỉ chứng nghiện ma túy nổi tiếng của Göring. Tuy nhiên, các tác dụng phụ nghiêm trọng đến mức quân đội đã phải cắt giảm việc sử dụng meth vào năm 1940. [113] Đến năm 1941, việc sử dụng bị hạn chế theo đơn của bác sĩ và quân đội, kiểm soát chặt chẽ việc phân phối thuốc. Các binh sĩ sẽ chỉ nhận được một vài viên mỗi lần và không được khuyến khích sử dụng chúng trong chiến đấu. Nhà sử học Łukasz Kamieński nói,

"A soldier going to battle on Pervitin usually found himself unable to perform effectively for the next day or two. Suffering from a drug hangover and looking more like a zombie than a great warrior, he had to recover from the side effects."

Nhiều binh sĩ trở nên bạo lực, gây ra tội ác chiến tranh với dân thường; những người khác tấn công các sĩ quan của chính họ.[114]

Buôn lậu ma tuý

Tam giác vàng (Đông Nam Á), là nhà sản xuất methamphetamin hàng đầu thế giới khi sản xuất đã chuyển sang Yaba và methamphetamin dạng tinh thể, bao gồm cả xuất khẩu sang Hoa Kỳ và khắp Đông, Đông Nam Á và Thái Bình Dương.[115]

Liên quan đến việc tăng tốc sản xuất ma túy tổng hợp trong khu vực, tổ chức Sam Gor của Trung Quốc ở Quảng Đông, còn được gọi là The Company, được hiểu là tổ chức tội phạm quốc tế chính chịu trách nhiệm về sự thay đổi này. [116] Tổ chức được tạo thành từ các thành viên của năm bộ ba khác nhau. Sam Gor bị cáo buộc kiểm soát 40% thị trường methamphetamin châu Á - Thái Bình Dương, chưa bao gồm buôn bán heroin và ketamin. Tổ chức đang hoạt động ở nhiều quốc gia, bao gồm Myanmar, Thái Lan, New Zealand, Úc, Nhật Bản, Trung Quốc và Đài Loan. Sam Gor trước đây sản xuất meth ở miền Nam Trung Quốc và hiện được cho là sản xuất chủ yếu ở Tam giác vàng, cụ thể là bang Shan, Myanmar, chịu trách nhiệm cho phần lớn tội phạm trong những năm gần đây.[117] Nhóm này được hiểu là do Tse Chi Lop, một trùm xã hội đen sinh ra ở Quảng Châu, Trung Quốc, cầm đầu.

Tình trạng pháp lý

Việc sản xuất, phân phối, bán và sở hữu methamphetamin bị hạn chế hoặc bất hợp pháp ở hầu như mọi khu vực pháp lý.[118][119] Methamphetamin được xếp vào lịch trình II của hiệp ước Công ước Liên hợp quốc về các chất ma túy.[120]

Chú thích

- ^ “methamphetamine”. Archived copy. Lexico. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 14 tháng 6 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 22 tháng 4 năm 2022.Quản lý CS1: bản lưu trữ là tiêu đề (liên kết)

- ^ Sellers EM, Tyndale RF (2000). “Mimicking gene defects to treat drug dependence”. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 909 (1): 233–246. Bibcode:2000NYASA.909..233S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06685.x. PMID 10911933. S2CID 27787938.

Methamphetamine, a central nervous system stimulant drug, is p-hydroxylated by CYP2D6 to less active p-OH-methamphetamine.

- ^ “Toxicity”. Methamphetamine. PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- ^ Courtney KE, Ray LA (tháng 10 năm 2014). “Methamphetamine: an update on epidemiology, pharmacology, clinical phenomenology, and treatment literature”. Drug Alcohol Depend. 143: 11–21. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.003. PMC 4164186. PMID 25176528.

- ^ a b “Chemical and Physical Properties”. Methamphetamine. PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- ^ a b c “Methamphetamine”. Drug profiles. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). 8 tháng 1 năm 2015. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 15 tháng 4 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 27 tháng 11 năm 2018.

The term metamfetamine (the International Non-Proprietary Name: INN) strictly relates to the specific enantiomer (S)-N,α-dimethylbenzeneethanamine.

Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ<ref>không hợp lệ: tên “EMCDDA profile” được định rõ nhiều lần, mỗi lần có nội dung khác - ^ a b “Identification”. Methamphetamine. DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 tháng 2 năm 2013. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 28 tháng 12 năm 2015. Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 1 năm 2014.

- ^ “Methedrine (methamphetamine hydrochloride): Uses, Symptoms, Signs and Addiction Treatment”. Addictionlibrary.org. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 4 tháng 3 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 1 năm 2016.

- ^ “Meth Slang Names”. MethhelpOnline. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 7 tháng 12 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 1 năm 2014.

- ^ “Methamphetamine and the law”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 28 tháng 1 năm 2015. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 12 năm 2014.

- ^ Yu S, Zhu L, Shen Q, Bai X, Di X (tháng 3 năm 2015). “Recent advances in methamphetamine neurotoxicity mechanisms and its molecular pathophysiology”. Behav. Neurol. 2015: 103969. doi:10.1155/2015/103969. PMC 4377385. PMID 25861156.

In 1971, METH was restricted by US law, although oral METH (Ovation Pharmaceuticals) continues to be used today in the USA as a second-line treatment for a number of medical conditions, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and refractory obesity [3].

- ^ “Enantiomer”. IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology. IUPAC Goldbook. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. 2009. doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02069. ISBN 9780967855097. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 17 tháng 3 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 3 năm 2014.

One of a pair of molecular entities which are mirror images of each other and non-superposable.

- ^ Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>sai; không có nội dung trong thẻ ref có tênPubChem Header - ^ “Part 341 – cold, cough, allergy, bronchodilator, and antiasthmatic drug products for over-the-counter human use”. Code of Federal Regulations Title 21: Subchapter D – Drugs for human use. United States Food and Drug Administration. tháng 4 năm 2015. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 25 tháng 12 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 7 tháng 3 năm 2016.

Topical nasal decongestants --(i) For products containing levmetamfetamine identified in 341.20(b)(1) when used in an inhalant dosage form. The product delivers in every 800 milliliters of air 0.04 to 0.150 milligrams of levmetamfetamine.

- ^ “Identification”. Levomethamphetamine. Pubchem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 6 tháng 10 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 4 tháng 9 năm 2017.

- ^ “Meth's aphrodisiac effect adds to drug's allure - Health - Addictions | NBC News”. web.archive.org. 12 tháng 8 năm 2013. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 12 tháng 8 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022.Quản lý CS1: bot: trạng thái URL ban đầu không rõ (liên kết)

- ^ Yu S, Zhu L, Shen Q, Bai X, Di X (2015). “Recent advances in methamphetamine neurotoxicity mechanisms and its molecular pathophysiology”. Behav Neurol. 2015: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2015/103969. PMC 4377385. PMID 25861156.

- ^ Krasnova IN, Cadet JL (tháng 5 năm 2009). “Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death”. Brain Res. Rev. 60 (2): 379–407. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.03.002. PMC 2731235. PMID 19328213.

Neuroimaging studies have revealed that METH can indeed cause neurodegenerative changes in the brains of human addicts (Aron and Paulus, 2007; Chang et al., 2007). These abnormalities include persistent decreases in the levels of dopamine transporters (DAT) in the orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the caudate-putamen (McCann et al., 1998, 2008; Sekine et al., 2003; Volkow et al., 2001a, 2001c). The density of serotonin transporters (5-HTT) is also decreased in the midbrain, caudate, putamen, hypothalamus, thalamus, the orbitofrontal, temporal, and cingulate cortices of METH-dependent individuals (Sekine et al., 2006) ...

Neuropsychological studies have detected deficits in attention, working memory, and decision-making in chronic METH addicts ...

There is compelling evidence that the negative neuropsychiatric consequences of METH abuse are due, at least in part, to drug-induced neuropathological changes in the brains of these METH-exposed individuals ...

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in METH addicts have revealed substantial morphological changes in their brains. These include loss of gray matter in the cingulate, limbic and paralimbic cortices, significant shrinkage of hippocampi, and hypertrophy of white matter (Thompson et al., 2004). In addition, the brains of METH abusers show evidence of hyperintensities in white matter (Bae et al., 2006; Ernst et al., 2000), decreases in the neuronal marker, N-acetylaspartate (Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007), reductions in a marker of metabolic integrity, creatine (Sekine et al., 2002) and increases in a marker of glial activation, myoinositol (Chang et al., 2002; Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007; Yen et al., 1994). Elevated choline levels, which are indicative of increased cellular membrane synthesis and turnover are also evident in the frontal gray matter of METH abusers (Ernst et al., 2000; Salo et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007). - ^ Krasnova IN, Cadet JL (tháng 5 năm 2009). “Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death”. Brain Res. Rev. 60 (2): 379–407. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.03.002. PMC 2731235. PMID 19328213.

Neuroimaging studies have revealed that METH can indeed cause neurodegenerative changes in the brains of human addicts (Aron and Paulus, 2007; Chang et al., 2007). These abnormalities include persistent decreases in the levels of dopamine transporters (DAT) in the orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the caudate-putamen (McCann et al., 1998, 2008; Sekine et al., 2003; Volkow et al., 2001a, 2001c). The density of serotonin transporters (5-HTT) is also decreased in the midbrain, caudate, putamen, hypothalamus, thalamus, the orbitofrontal, temporal, and cingulate cortices of METH-dependent individuals (Sekine et al., 2006) ...

Neuropsychological studies have detected deficits in attention, working memory, and decision-making in chronic METH addicts ...

There is compelling evidence that the negative neuropsychiatric consequences of METH abuse are due, at least in part, to drug-induced neuropathological changes in the brains of these METH-exposed individuals ...

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in METH addicts have revealed substantial morphological changes in their brains. These include loss of gray matter in the cingulate, limbic and paralimbic cortices, significant shrinkage of hippocampi, and hypertrophy of white matter (Thompson et al., 2004). In addition, the brains of METH abusers show evidence of hyperintensities in white matter (Bae et al., 2006; Ernst et al., 2000), decreases in the neuronal marker, N-acetylaspartate (Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007), reductions in a marker of metabolic integrity, creatine (Sekine et al., 2002) and increases in a marker of glial activation, myoinositol (Chang et al., 2002; Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007; Yen et al., 1994). Elevated choline levels, which are indicative of increased cellular membrane synthesis and turnover are also evident in the frontal gray matter of METH abusers (Ernst et al., 2000; Salo et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007). - ^ “Identification”. Methamphetamine. DrugBank. University of Alberta. ngày 8 tháng 2 năm 2013.

- ^ “Methedrine (methamphetamine hydrochloride): Uses, Symptoms, Signs and Addiction Treatment”. Addictionlibrary.org. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 4 tháng 3 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 1 năm 2016.

- ^ a b c “Desoxyn Prescribing Information” (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. tháng 12 năm 2013. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 2 tháng 1 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 1 năm 2014.

- ^ Hart CL, Marvin CB, Silver R, Smith EE (tháng 2 năm 2012). “Is cognitive functioning impaired in methamphetamine users? A critical review”. Neuropsychopharmacology. 37 (3): 586–608. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.276. PMC 3260986. PMID 22089317.

- ^ “Methedrine (methamphetamine hydrochloride): Uses, Symptoms, Signs and Addiction Treatment”. Addictionlibrary.org. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 4 tháng 3 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 1 năm 2016.

- ^ “Meth Slang Names”. MethhelpOnline. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 7 tháng 12 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 1 năm 2014.

- ^ “Methamphetamine and the law”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 28 tháng 1 năm 2015. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 12 năm 2014.

- ^ a b “Desoxyn Prescribing Information” (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. tháng 12 năm 2013. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 2 tháng 1 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 1 năm 2014.

- ^ “Desoxyn Gradumet Side Effects”. Drugs.com. 19 tháng 3 năm 2022. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 18 tháng 10 năm 2022. Truy cập ngày 18 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f San Francisco Meth Zombies (TV documentary). National Geographic Channel. tháng 8 năm 2013. ASIN B00EHAOBAO. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 8 tháng 7 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 7 tháng 7 năm 2016.

- ^ Kiều Trang, Cục phòng, chống HIV/AIDS - Bộ Y tế Việt Nam. “Các chất ma túy thường dùng trong hoạt động Chemsex”. vaac.gov.vn. Truy cập ngày 19 tháng 10 năm 2023.

- ^ Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE (2011). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies (ấn bản 9). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. tr. 1080. ISBN 978-0-07-160593-9.

- ^ a b c d “Desoxyn Prescribing Information” (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. tháng 12 năm 2013. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 2 tháng 1 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 1 năm 2014.

- ^ “AccessMedicine | Miscellaneous Sympathomimetic Agonists”. web.archive.org. 10 tháng 11 năm 2013. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 10 tháng 11 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022.Quản lý CS1: bot: trạng thái URL ban đầu không rõ (liên kết)

- ^ “Desoxyn Prescribing Information” (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. tháng 12 năm 2013. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 2 tháng 1 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 1 năm 2014.

- ^ “Meth Sores”. Drug Rehab (bằng tiếng Anh). Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- ^ “Methamphetamine: Facts, effects, and health risks”. www.medicalnewstoday.com (bằng tiếng Anh). 30 tháng 9 năm 2022. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- ^ Abuse, National Institute on Drug (--). “What are the long-term effects of methamphetamine misuse?”. National Institute on Drug Abuse (bằng tiếng Anh). Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022. Kiểm tra giá trị ngày tháng trong:

|ngày=(trợ giúp) - ^ “Methamphetamine: Facts, effects, and health risks”. www.medicalnewstoday.com (bằng tiếng Anh). 30 tháng 9 năm 2022. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- ^ Abuse, National Institute on Drug (--). “What are the long-term effects of methamphetamine misuse?”. National Institute on Drug Abuse (bằng tiếng Anh). Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022. Kiểm tra giá trị ngày tháng trong:

|ngày=(trợ giúp) - ^ Abuse, National Institute on Drug (20 tháng 1 năm 2022). “Overdose Death Rates”. National Institute on Drug Abuse (bằng tiếng Anh). Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- ^ Bluecrest (17 tháng 6 năm 2019). “Meth Overdose Symptoms, Effects & Treatment | BlueCrest”. Bluecrest Recovery Center (bằng tiếng Anh). Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- ^ Hussain, Fahmida; Frare, Robert W.; Py Berrios, Karen L. (tháng 7 năm 2012). “Drug abuse identification and pain management in dental patients: a case study and literature review”. General Dentistry. 60 (4): 334–345, quiz 346–347. ISSN 0363-6771. PMID 22782046.

- ^ “ADA.org: A-Z Topics: Methamphetamine Use (Meth Mouth)”. web.archive.org. 1 tháng 6 năm 2008. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 1 tháng 6 năm 2008. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022.Quản lý CS1: bot: trạng thái URL ban đầu không rõ (liên kết)

- ^ Hussain, Fahmida; Frare, Robert W.; Py Berrios, Karen L. (tháng 7 năm 2012). “Drug abuse identification and pain management in dental patients: a case study and literature review”. General Dentistry. 60 (4): 334–345, quiz 346–347. ISSN 0363-6771. PMID 22782046.

- ^ Hart, Carl L; Marvin, Caroline B; Silver, Rae; Smith, Edward E (16 tháng 11 năm 2011). “Is Cognitive Functioning Impaired in Methamphetamine Users? A Critical Review”. Neuropsychopharmacology (bằng tiếng Anh). 37 (3): 586–608. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.276. ISSN 0893-133X.

- ^ Halkitis, Perry N.; Mukherjee, Preetika Pandey; Palamar, Joseph J. (26 tháng 7 năm 2008). “Longitudinal Modeling of Methamphetamine Use and Sexual Risk Behaviors in Gay and Bisexual Men”. AIDS and Behavior (bằng tiếng Anh). 13 (4): 783–791. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9432-y. ISSN 1090-7165.

- ^ Halkitis, Perry N.; Mukherjee, Preetika Pandey; Palamar, Joseph J. (26 tháng 7 năm 2008). “Longitudinal Modeling of Methamphetamine Use and Sexual Risk Behaviors in Gay and Bisexual Men”. AIDS and Behavior (bằng tiếng Anh). 13 (4): 783–791. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9432-y. ISSN 1090-7165.

- ^ a b Patrick Moore (tháng 6 năm 2005). “We Are Not OK”. VillageVoice. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 4 tháng 6 năm 2011. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 1 năm 2011.

- ^ a b “Desoxyn Prescribing Information” (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. tháng 12 năm 2013. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 2 tháng 1 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 1 năm 2014.

- ^ a b “Wayback Machine” (PDF). web.archive.org. 16 tháng 8 năm 2008. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 16 tháng 8 năm 2008. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022. Chú thích có tiêu đề chung (trợ giúp)Quản lý CS1: bot: trạng thái URL ban đầu không rõ (liên kết)

- ^ “Amphetamines - Special Subjects”. Merck Manuals Professional Edition (bằng tiếng Anh). Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- ^ “AccessMedicine | Miscellaneous Sympathomimetic Agonists”. web.archive.org. 10 tháng 11 năm 2013. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 10 tháng 11 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022.Quản lý CS1: bot: trạng thái URL ban đầu không rõ (liên kết)

- ^ “Desoxyn Prescribing Information” (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. tháng 12 năm 2013. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 2 tháng 1 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 1 năm 2014.

- ^ Rusyniak, Daniel E. (1 tháng 8 năm 2011). “Neurologic manifestations of chronic methamphetamine abuse”. Neurologic clinics. 29 (3): 641–655. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2011.05.004. ISSN 0733-8619. PMC 3148451. PMID 21803215.

- ^ Archive, View Author; feed, Get author RSS (26 tháng 12 năm 2021). “Missouri sword-slay suspect smiles for mug shot after allegedly killing beau”. New York Post (bằng tiếng Anh). Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- ^ Darke, Shane; Kaye, Sharlene; McKETIN, Rebecca; Duflou, Johan (tháng 5 năm 2008). “Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use”. Drug and Alcohol Review (bằng tiếng Anh). 27 (3): 253–262. doi:10.1080/09595230801923702.

- ^ Yu, Shaobin; Zhu, Ling; Shen, Qiang; Bai, Xue; Di, Xuhui (2015). “Recent Advances in Methamphetamine Neurotoxicity Mechanisms and Its Molecular Pathophysiology”. Behavioural Neurology (bằng tiếng Anh). 2015: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2015/103969. ISSN 0953-4180.

- ^ Krasnova IN, Cadet JL (tháng 5 năm 2009). “Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death”. Brain Res. Rev. 60 (2): 379–407. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.03.002. PMC 2731235. PMID 19328213.

Neuroimaging studies have revealed that METH can indeed cause neurodegenerative changes in the brains of human addicts (Aron and Paulus, 2007; Chang et al., 2007). These abnormalities include persistent decreases in the levels of dopamine transporters (DAT) in the orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the caudate-putamen (McCann et al., 1998, 2008; Sekine et al., 2003; Volkow et al., 2001a, 2001c). The density of serotonin transporters (5-HTT) is also decreased in the midbrain, caudate, putamen, hypothalamus, thalamus, the orbitofrontal, temporal, and cingulate cortices of METH-dependent individuals (Sekine et al., 2006) ...

Neuropsychological studies have detected deficits in attention, working memory, and decision-making in chronic METH addicts ...

There is compelling evidence that the negative neuropsychiatric consequences of METH abuse are due, at least in part, to drug-induced neuropathological changes in the brains of these METH-exposed individuals ...

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in METH addicts have revealed substantial morphological changes in their brains. These include loss of gray matter in the cingulate, limbic and paralimbic cortices, significant shrinkage of hippocampi, and hypertrophy of white matter (Thompson et al., 2004). In addition, the brains of METH abusers show evidence of hyperintensities in white matter (Bae et al., 2006; Ernst et al., 2000), decreases in the neuronal marker, N-acetylaspartate (Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007), reductions in a marker of metabolic integrity, creatine (Sekine et al., 2002) and increases in a marker of glial activation, myoinositol (Chang et al., 2002; Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007; Yen et al., 1994). Elevated choline levels, which are indicative of increased cellular membrane synthesis and turnover are also evident in the frontal gray matter of METH abusers (Ernst et al., 2000; Salo et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007). - ^ Cruickshank, Christopher C.; Dyer, Kyle R. (tháng 7 năm 2009). “A review of the clinical pharmacology of methamphetamine”. Addiction (bằng tiếng Anh). 104 (7): 1085–1099. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02564.x.

- ^ Carvalho, Márcia; Carmo, Helena; Costa, Vera Marisa; Capela, João Paulo; Pontes, Helena; Remião, Fernando; Carvalho, Félix; Bastos, Maria de Lourdes (1 tháng 8 năm 2012). “Toxicity of amphetamines: an update”. Archives of Toxicology (bằng tiếng Anh). 86 (8): 1167–1231. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5. ISSN 1432-0738.

- ^ a b Yu, Shaobin; Zhu, Ling; Shen, Qiang; Bai, Xue; Di, Xuhui (2015). “Recent Advances in Methamphetamine Neurotoxicity Mechanisms and Its Molecular Pathophysiology”. Behavioural Neurology. 2015: 103969. doi:10.1155/2015/103969. ISSN 0953-4180. PMC 4377385. PMID 25861156.

- ^ Cisneros, Irma E.; Ghorpade, Anuja (tháng 10 năm 2014). “Methamphetamine and HIV-1-induced neurotoxicity: Role of trace amine associated receptor 1 cAMP signaling in astrocytes”. Neuropharmacology (bằng tiếng Anh). 85: 499–507. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.011. ISSN 0028-3908.

- ^ Krasnova IN, Cadet JL (tháng 5 năm 2009). “Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death”. Brain Res. Rev. 60 (2): 379–407. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.03.002. PMC 2731235. PMID 19328213.

Neuroimaging studies have revealed that METH can indeed cause neurodegenerative changes in the brains of human addicts (Aron and Paulus, 2007; Chang et al., 2007). These abnormalities include persistent decreases in the levels of dopamine transporters (DAT) in the orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the caudate-putamen (McCann et al., 1998, 2008; Sekine et al., 2003; Volkow et al., 2001a, 2001c). The density of serotonin transporters (5-HTT) is also decreased in the midbrain, caudate, putamen, hypothalamus, thalamus, the orbitofrontal, temporal, and cingulate cortices of METH-dependent individuals (Sekine et al., 2006) ...

Neuropsychological studies have detected deficits in attention, working memory, and decision-making in chronic METH addicts ...

There is compelling evidence that the negative neuropsychiatric consequences of METH abuse are due, at least in part, to drug-induced neuropathological changes in the brains of these METH-exposed individuals ...

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in METH addicts have revealed substantial morphological changes in their brains. These include loss of gray matter in the cingulate, limbic and paralimbic cortices, significant shrinkage of hippocampi, and hypertrophy of white matter (Thompson et al., 2004). In addition, the brains of METH abusers show evidence of hyperintensities in white matter (Bae et al., 2006; Ernst et al., 2000), decreases in the neuronal marker, N-acetylaspartate (Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007), reductions in a marker of metabolic integrity, creatine (Sekine et al., 2002) and increases in a marker of glial activation, myoinositol (Chang et al., 2002; Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007; Yen et al., 1994). Elevated choline levels, which are indicative of increased cellular membrane synthesis and turnover are also evident in the frontal gray matter of METH abusers (Ernst et al., 2000; Salo et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007). - ^ Yuan J, Hatzidimitriou G, Suthar P, Mueller M, McCann U, Ricaurte G (tháng 3 năm 2006). “Relationship between temperature, dopaminergic neurotoxicity, and plasma drug concentrations in methamphetamine-treated squirrel monkeys”. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 316 (3): 1210–1218. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.096503. PMID 16293712. S2CID 11909155. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 31 tháng 10 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 28 tháng 12 năm 2019.

- ^ a b Krasnova IN, Cadet JL (tháng 5 năm 2009). “Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death”. Brain Res. Rev. 60 (2): 379–407. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.03.002. PMC 2731235. PMID 19328213.

Neuroimaging studies have revealed that METH can indeed cause neurodegenerative changes in the brains of human addicts (Aron and Paulus, 2007; Chang et al., 2007). These abnormalities include persistent decreases in the levels of dopamine transporters (DAT) in the orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the caudate-putamen (McCann et al., 1998, 2008; Sekine et al., 2003; Volkow et al., 2001a, 2001c). The density of serotonin transporters (5-HTT) is also decreased in the midbrain, caudate, putamen, hypothalamus, thalamus, the orbitofrontal, temporal, and cingulate cortices of METH-dependent individuals (Sekine et al., 2006) ...

Neuropsychological studies have detected deficits in attention, working memory, and decision-making in chronic METH addicts ...

There is compelling evidence that the negative neuropsychiatric consequences of METH abuse are due, at least in part, to drug-induced neuropathological changes in the brains of these METH-exposed individuals ...

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in METH addicts have revealed substantial morphological changes in their brains. These include loss of gray matter in the cingulate, limbic and paralimbic cortices, significant shrinkage of hippocampi, and hypertrophy of white matter (Thompson et al., 2004). In addition, the brains of METH abusers show evidence of hyperintensities in white matter (Bae et al., 2006; Ernst et al., 2000), decreases in the neuronal marker, N-acetylaspartate (Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007), reductions in a marker of metabolic integrity, creatine (Sekine et al., 2002) and increases in a marker of glial activation, myoinositol (Chang et al., 2002; Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007; Yen et al., 1994). Elevated choline levels, which are indicative of increased cellular membrane synthesis and turnover are also evident in the frontal gray matter of METH abusers (Ernst et al., 2000; Salo et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007). - ^ a b • Cisneros IE, Ghorpade A (tháng 10 năm 2014). “Methamphetamine and HIV-1-induced neurotoxicity: role of trace amine associated receptor 1 cAMP signaling in astrocytes”. Neuropharmacology. 85: 499–507. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.011. PMC 4315503. PMID 24950453.

TAAR1 overexpression significantly decreased EAAT-2 levels and glutamate clearance ... METH treatment activated TAAR1 leading to intracellular cAMP in human astrocytes and modulated glutamate clearance abilities. Furthermore, molecular alterations in astrocyte TAAR1 levels correspond to changes in astrocyte EAAT-2 levels and function.

- ^ a b Kaushal N, Matsumoto RR (tháng 3 năm 2011). “Role of sigma receptors in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity”. Curr Neuropharmacol. 9 (1): 54–57. doi:10.2174/157015911795016930. PMC 3137201. PMID 21886562.

σ Receptors seem to play an important role in many of the effects of METH. They are present in the organs that mediate the actions of METH (e.g. brain, heart, lungs) [5]. In the brain, METH acts primarily on the dopaminergic system to cause acute locomotor stimulant, subchronic sensitized, and neurotoxic effects. σ Receptors are present on dopaminergic neurons and their activation stimulates dopamine synthesis and release [11–13]. σ-2 Receptors modulate DAT and the release of dopamine via protein kinase C (PKC) and Ca2+-calmodulin systems [14].

σ-1 Receptor antisense and antagonists have been shown to block the acute locomotor stimulant effects of METH [4]. Repeated administration or self administration of METH has been shown to upregulate σ-1 receptor protein and mRNA in various brain regions including the substantia nigra, frontal cortex, cerebellum, midbrain, and hippocampus [15, 16]. Additionally, σ receptor antagonists ... prevent the development of behavioral sensitization to METH [17, 18]. ...

σ Receptor agonists have been shown to facilitate dopamine release, through both σ-1 and σ-2 receptors [11–14]. - ^ a b Rodvelt KR, Miller DK (tháng 9 năm 2010). “Could sigma receptor ligands be a treatment for methamphetamine addiction?”. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 3 (3): 156–162. doi:10.2174/1874473711003030156. PMID 21054260.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). “Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders”. Trong Sydor A, Brown RY (biên tập). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (ấn bản 2). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. tr. 364–375. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ Nestler EJ (tháng 12 năm 2013). “Cellular basis of memory for addiction”. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Mặc cho tầm quan trọng của nhiều yếu tố tâm lý xã hội, nhưng về bản chất, nghiện ma túy bao gồm một quá trình sinh học: khả năng tiếp xúc nhiều lần với một loại thuốc lạm dụng để tạo ra những thay đổi trong não dễ bị tổn thương dẫn tới việc kiếm tìm và uống thuốc mang tính bắt buộc, và mất khả năng kiểm soát việc sử dụng ma túy, điều xác định tình trạng nghiện. ... Một tài liệu lớn đã chứng minh rằng loại cảm ứng ΔFosB như vậy trong các tế bào thần kinh loại D1 [nhân cạp - nucleus accumbens] làm tăng độ nhạy cảm của động vật đối với ma túy cũng như các phần thưởng tự nhiên và thúc đẩy việc tự cho phép sử dụng ma tùy, có lẽ thông qua quá trình củng cố tích cực ... Một mục tiêu ΔFosB khác là cFos: bởi ΔFosB tích lũy khi tiếp xúc với thuốc lặp đi lặp lại, nó ức chế c-Fos và góp phần chuyển đổi phân tử, theo đó ΔFosB được chọn lọc trong trạng thái điều trị ma túy mãn tính.41 ... Hơn nữa, ngày càng có nhiều bằng chứng cho thấy, mặc dù có nhiều rủi ro di truyền gây nghiện trong dân số, việc tiếp xúc với liều thuốc đủ cao trong thời gian dài có thể biến một người có tải lượng gen tương đối thấp thành con nghiện.

- ^ “Glossary of Terms”. Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Department of Neuroscience. Truy cập ngày 9 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (tháng 1 năm 2016). “Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction”. New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

Rối loạn sử dụng chất: Thuật ngữ chẩn đoán trong phiên bản thứ năm của Cẩm nang chẩn đoán và thống kê rối loạn tâm thần (DSM-5) đề cập đến việc sử dụng rượu hoặc các loại thuốc khác gây suy giảm đáng kể về mặt lâm sàng và chức năng, như các vấn đề về sức khỏe, khuyết tật, và không đáp ứng các trách nhiệm chính tại nơi làm việc, trường học hoặc nhà. Tùy thuộc vào mức độ nghiêm trọng, rối loạn này được phân loại là nhẹ, trung bình hoặc nặng.

Nghiện: Một thuật ngữ được sử dụng để chỉ giai đoạn rối loạn sử dụng chất nghiêm trọng và mãn tính nhất, trong đó có sự mất tự chủ đáng kể, được chỉ định bằng cách uống thuốc bắt buộc mặc dù muốn ngừng dùng thuốc. Trong DSM-5, thuật ngữ 'nghiện' đồng nghĩa với việc phân loại rối loạn sử dụng chất nghiêm trọng. - ^ a b c Renthal W, Nestler EJ (tháng 9 năm 2009). “Chromatin regulation in drug addiction and depression”. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 11 (3): 257–268. PMC 2834246. PMID 19877494.

[Psychostimulants] increase cAMP levels in striatum, which activates protein kinase A (PKA) and leads to phosphorylation of its targets. This includes the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), the phosphorylation of which induces its association with the histone acetyltransferase, CREB binding protein (CBP) to acetylate histones and facilitate gene activation. This is known to occur on many genes including fosB and c-fos in response to psychostimulant exposure. ΔFosB is also upregulated by chronic psychostimulant treatments, and is known to activate certain genes (eg, cdk5) and repress others (eg, c-fos) where it recruits HDAC1 as a corepressor. ... Chronic exposure to psychostimulants increases glutamatergic [signaling] from the prefrontal cortex to the NAc. Glutamatergic signaling elevates Ca2+ levels in NAc postsynaptic elements where it activates CaMK (calcium/calmodulin protein kinases) signaling, which, in addition to phosphorylating CREB, also phosphorylates HDAC5.

Figure 2: Psychostimulant-induced signaling events - ^ Broussard JI (tháng 1 năm 2012). “Co-transmission of dopamine and glutamate”. The Journal of General Physiology. 139 (1): 93–96. doi:10.1085/jgp.201110659. PMC 3250102. PMID 22200950.