Khác biệt giữa bản sửa đổi của “Ankylosaurus”

Thẻ: Trình soạn thảo mã nguồn 2017 |

Thẻ: Trình soạn thảo mã nguồn 2017 |

||

| Dòng 166: | Dòng 166: | ||

*{{Commons category-inline}} |

*{{Commons category-inline}} |

||

== |

==Chú thích== |

||

'''Ghi chú''' |

|||

{{tham khảo|2}} |

|||

{{Reflist|group=nb}} |

|||

'''Trích dẫn''' |

|||

{{Reflist|30em|refs= |

|||

<ref name=HCFF>{{cite web|author=Bigelow, P. |title=Cretaceous 'Hell Creek Faunal Facies'; Late Maastrichtian |url=http://www.scn.org/~bh162/hellcreek2.html |accessdate=2014-03-24 |archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/5mqfIGR8Z?url=http://www.scn.org/~bh162/hellcreek2.html |archivedate=17 January 2010 |deadurl=no }}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=WETAL04>{{cite book|author1=Weishampel, D. B. |author2=Barrett, P. M. |author3=Coria, R. A. |author4=Le Loeuff, J. |author5=Xu X. |author6=Zhao X. |author7=Sahni, A. |author8=Gomani, E. M. P. |author9=Noto, C. R. |year=2004|contribution=Dinosaur Distribution|editor1=Weishampel, D. B. |editor2=Dodson, P. |editor3=Osmolska, H.. |title=The Dinosauria (2nd)|publisher=University of California Press|pages=517–606|isbn=0-520-24209-2}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="eberth1997">{{cite book|author =Eberth, D. A.|year=1997|contribution=Edmonton Group|editor1=Currie, P. J. |editor2=Padian, K. |title=The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs|publisher=Academic Press|pages=199–204|isbn=978-0-12-226810-6}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="breithaupt1997">{{cite book|author =Breithaupt, B. H.|year=1997|contribution=Lance Formation"|editors=Currie, P.J.; Padian, K.|title=The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs|publisher=Academic Press|pages=394–95|isbn=978-0-12-226810-6}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="lofgren1997">{{cite book|author =Lofgren, D. F.|year=1997|contribution=Hell Creek Formation|editor1=Currie, P.J. |editor2=Padian, K. |title=The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs|publisher=Academic Press|pages=302–03|isbn=978-0-12-226810-6}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="carpenter2001">{{cite book |author =Carpenter, K. |year=2001 |title=The Armored Dinosaurs |editor=Carpenter, K. |contribution=Chapter 21: Phylogenetic Analysis of the Ankylosauria |pages=454–83 |isbn=0-253-33964-2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=04tQ5_qJN8MC&lpg=PP1&dq=The%20Armored%20Dinosaurs&pg=PA455#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="brown1908">{{cite journal |author =Brown, B. |year=1908 |title=The Ankylosauridae, a new family of armored dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous |journal=Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History |series=24 |pages=187–201 |hdl=2246/1435 }}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="thulborn1993">{{cite journal |author =Thulborn, T. |year=1993 |title=Mimicry in ankylosaurid dinosaurs |journal=Record of the South Australian Museum |series=27 |pages=151–58}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=arbour>{{cite journal|author =Arbour, V. M.|year=2009|title= Estimating impact forces of tail club strikes by ankylosaurid dinosaurs|journal=PLoS ONE |volume=4|issue=8|page=e6738|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0006738|bibcode=2009PLoSO...4.6738A|pmid=19707581|pmc=2726940}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="carpenter2004">{{cite journal |author =Carpenter, K. |year=2004 |title=Redescription of ''Ankylosaurus magniventris'' Brown 1908 (Ankylosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Western Interior of North America |journal=Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences |volume=41 |issue=8 |pages=961–86|doi=10.1139/e04-043|bibcode=2004CaJES..41..961C|url=http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/pdf/10.1139/e04-043}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Burns Postcrania">{{cite journal|last1=Burns|first1=M|last2=Tumanova|first2=T|last3=Currie|first3=P|title=Postcrania of juvenile ''Pinacosaurus grangeri'' (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Alagteeg Formation, Alag Teeg, Mongolia: implications for ontogenetic allometry in ankylosaurs|journal=Journal of Paleontology|date=2015|volume=89|issue=1|pages=168–182|doi=10.1017/jpa.2014.14}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="vickaryousetal2004">{{cite book|authors=Vickaryous, M. K., Maryanska, T.; Weishampel, D. B.|contribution=Ankylosauria|editor1=Weishampel, D. B. |editor2=Dodson, P. |editor3=Osmólska, H. |year=2004 |title=The Dinosauria |publisher=University of California Press |pages=363–92 |isbn=0-520-24209-2}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="johnson1997">{{cite book|author =Johnson, K. R.|year=1997|contribution=Hell Creek Flora|editor1=Currie, P. J. |editor2=Padian, K. |title=The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs|publisher=Academic Press|pages=300–02|isbn=978-0-12-226810-6}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=pronunciation>{{cite web|author=Creisler, B. |title=Dinosauria Translation and Pronunciation Guide A |date=July 7, 2003 |url=http://www.dinosauria.com/dml/names/dinoa.htm |accessdate=September 3, 2010 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20100818013919/http://www.dinosauria.com/dml/names/dinoa.htm |archivedate=August 18, 2010 |deadurl=yes |df= }}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="hindlimb">{{cite journal|author =Coombs, W.|year=1979|title= |

|||

Osteology and myology of the hindlimb in the Ankylosauria (Reptillia, Ornithischia)|journal=Journal of Paleontology|volume=53|issue=3|pages=666–84|jstor=1304004}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Witmer">{{cite journal|authors=Miyashita, T., Arbour V. M.; Witmer L. M.; Currie, P. J.|year=2011|title=The internal cranial morphology of an armoured dinosaur ''Euoplocephalus'' corroborated by X-ray computed tomographic reconstruction|journal=Journal of Anatomy|volume=219|issue=6|pages=661–75|doi=10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01427.x|pmid=21954840|pmc=3237876|url=http://www.oucom.ohiou.edu/dbms-witmer/Downloads/2011_Miyashita_et_al._Euoplocephalus_head_anatomy.pdf|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924062640/http://www.oucom.ohiou.edu/dbms-witmer/Downloads/2011_Miyashita_et_al._Euoplocephalus_head_anatomy.pdf|archivedate=2015-09-24|df=}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="digger">{{cite journal|author =Coombs, W.|year=1978|title=Forelimb muscles of the Ankylosauria (Reptilia, Ornithischia)|journal=Journal of Paleontology|volume=52|issue=3|pages=642–57|jstor=1303969}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Currie2011">{{cite journal|author1=Currie, P. J. |author2=Badamgarav, D. |author3=Koppelhus, E. B. |author4=Sissons, R. |author5=Vickaryous, M. K. |year=2011|title=Hands, feet, and behaviour in ''Pinacosaurus'' (Dinosauria: Ankylosauridae)|journal=Acta Palaeontologica Polonica|volume=56|issue=3|pages=489–504|doi=10.4202/app.2010.0055}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Scheyer">{{cite journal|author1=Scheyer, T. M. |author2=Sander, P. M. |year=2004|title=Histology of ankylosaur osteoderms: implications for systematics and function|journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology|volume=24|issue=4|pages=874–93|jstor=4524782|doi=10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0874:hoaoif]2.0.co;2}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Carpenter1982>{{cite journal|author = Carpenter, K.|year=1982|title=Skeletal and dermal armor reconstruction of ''Euoplocephalus tutus'' (Ornithischia: Ankylosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous Oldman Formation of Alberta|journal=Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences|volume=19|issue=4|pages=689–97|doi=10.1139/e82-058|bibcode=1982CaJES..19..689C}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Hans1969">{{cite journal|author =Haas, G.|year=1969|title=On the jaw musculature of ankylosaurs|journal=American Museum Novitates|volume=2399|pages=1–11 |hdl=2246/2609 }}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Rybzynski2001>{{cite book|author1=Rybczynski, N. |author2=Vickaryous, M. K. |year=2001|contribution=Chapter 14: Evidence of Complex Jaw Movement in the Late Cretaceous Ankylosaurid, ''Euoplocephalus tutus'' (Dinosauria: Thyreophora)|pages=299–317|editor=K. Carpenter|title=The Armored Dinosaurs|publisher=Indiana University Press|isbn=978-0-253-33964-5}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Coombs1972>{{cite journal|author=Coombs W.|year=1972|title=The Bony Eyelid of ''Euoplocephalus'' (Reptilia, Ornithischia)|journal=Journal of Paleontology|volume=46|issue=5|pages=637–50|jstor=1303019}}.</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Maryanska1977>{{cite journal|author =Maryanska, T.|year=1977|title=Ankylosauridae (Dinosauria) from Mongolia|journal=Palaeontologia polonica|volume=37|pages=85–151 | url= http://palaeontologia.pan.pl/Archive/1977-37_85-151_19-36.pdf}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="coombs">{{cite journal|author =Coombs, W. P.|title=Theoretical aspects of cursorial adaptations in dinosaurs |journal=[[The Quarterly Review of Biology]] |volume=53 |year=1978 |pages=393–418 |doi=10.1086/410790 |issue=4}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Oxford">{{cite book |author1=Liddell, H. G. |author2=Scott, R. | edition=abridged | isbn=0-19-910207-4 | origyear=1871 | title=[[A Greek-English Lexicon]] | publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] | year=1980 | page=5}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="osborn1905">{{cite journal|author =Osborn, H. F. |year=1905 |title=Tyrannosaurus and other Cretaceous carnivorous dinosaurs |journal=Bulletin of the AMNH |volume=21 |issue=14 |pages=259–265 |publisher=[[American Museum of Natural History]] |hdl=2246/1464 }}</ref> |

|||

<ref name = "osborn1923">{{cite journal|author =Osborn, H. F.|year=1923|title=Two Lower Cretaceous dinosaurs of Mongolia|journal=American Museum Novitates|volume=95|pages=1–10 |hdl=2246/3267 }}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Coombs teeth">{{cite book|author =Coombs, W.|year=1990|contribution=Teeth and taxonomy in ankylosaurs|editors=Carpenter, K. Currie, P. J.|title=Dinosaur systematics: Approaches and perspectives|pages=269–79|publisher=Cambridge University Press |url=https://books.google.com/?id=6ZV1KcVNM18C&pg=PA269|isbn=978-0-521-43810-0}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Coombs1978">{{cite journal|author =Coombs, W.|year=1978|title=The families of the ornithischian dinosaur order Ankylosauria|journal=Journal of Paleontology|volume=21|issue=1|pages=143–170|url=http://cdn.palass.org/publications/palaeontology/volume_21/pdf/vol21_part1_pp143-170.pdf}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Williston1908">{{cite journal|author =Williston, S. W.|year=1908|title=Review: The Ankylosauridae|journal=The American Naturalist|volume=42|issue=501|pages=629–30|doi=10.1086/278987|jstor=2455817}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="tongue">{{cite journal|author1=Hill, R. V. |author2=D'Emic, M. D. |author3=Bever, G. S. |author4=Norell, M. A. |year=2015|title=A complex hyobranchial apparatus in a Cretaceous dinosaur and the antiquity of avian paraglossalia|journal=Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society|pages=892–909|doi=10.1111/zoj.12293|volume=175|issue=4}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="thompson">{{Cite journal | last1 = Thompson | first1 = R. S. | last2 = Parish | first2 = J. C. | last3 = Maidment | first3 = S. C. R. | last4 = Barrett | first4 = P. M. | title = Phylogeny of the ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora) | doi = 10.1080/14772019.2011.569091 | journal = Journal of Systematic Palaeontology | volume = 10 | issue = 2 | pages = 301–312 | year = 2012 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Arbour2014II">{{cite journal|last=Arbour|first=V.M.|last2=Currie|first2=P.J.|last3=Badamgarav|first3=D.|year=2014|title=The ankylosaurid dinosaurs of the Upper Cretaceous Baruungoyot and Nemegt formations of Mongolia|journal=Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society|volume=172|issue=3|pages=631–652|doi=10.1111/zoj.12185}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="systematics ankylosaurid">{{cite journal|author1=Arbour, V. M. |author2=Currie, P. J. |year=2015|title=Systematics, phylogeny and palaeobiogeography of the ankylosaurid dinosaurs|journal=Journal of Systematic Palaeontology|volume=14|issue=5|pages=1–60|doi=10.1080/14772019.2015.1059985}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="glut1997">{{Cite book| publisher = McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers| isbn = 978-0-375-82419-7| last = Glut| first = D. F.| title = Dinosaurs, the encyclopedia| year = 1997 |chapter=Ankylosaurus |pages='''141–143'''}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="carpenter1982b">{{Cite journal| volume = 20| issue = 2| pages = 123–134| last = Carpenter| first = K.| title = Baby dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous Lance and Hell Creek formations and a description of a new species of theropod| journal = Rocky Mountain Geology| date = 1982| url = http://rmg.geoscienceworld.org/content/20/2/123.short}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Các chủ đề|Khủng long|Sinh học}} |

{{Các chủ đề|Khủng long|Sinh học}} |

||

Phiên bản lúc 20:34, ngày 21 tháng 7 năm 2018

| Ankylosaurus | |

|---|---|

| Khoảng thời gian tồn tại: tầng Maastricht của Phấn Trắng muộn, 68–66 triệu năm trước đây | |

| |

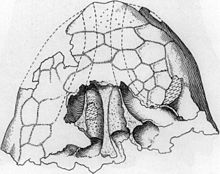

| Mặt trước của mô hình sọ Ankylosaurus (AMNH 5214), Bảo tàng Rockies, Montana | |

| Phân loại khoa học | |

| Giới: | Animalia |

| Ngành: | Chordata |

| Lớp: | Reptilia |

| nhánh: | Dinosauria |

| Bộ: | †Ornithischia |

| Phân bộ: | †Ankylosauria |

| Họ: | †Ankylosauridae |

| Chi: | †Ankylosaurus Brown, 1908 |

| Loài | |

| |

Ankylosaurus (/ˌæŋkəloʊˈsɔːrəs/[1], nghĩa là "thằn lằn hợp nhất") là một chi khủng long bọc giáp. Những hóa thạch của chi này được tìm thấy ở các thành hệ địa chất miền tây Bắc Mỹ có niên đại vào cuối kỷ Phấn trắng, khoảng 68-66 triệu trăm trước đây, làm cho Ankylosaurus trở thành một trong những giống khủng long phi điểu cuối cùng còn tồn tại trước khi sự kiện tuyệt chủng kỷ Creta-Đệ tam xảy ra. Được đặt tên bởi Barnum Brown vào năm 1908; loài duy nhất trong chi là A. magniventris ("bụng lớn"). Dù đã tìm thấy một số mẫu vật của chi này, hóa thạch xương hoàn chỉnh vẫn chưa có. Tuy thế, Ankylosaurus vẫn thường được xem là archetype của phân bộ Giáp long (Ankylosauria) này, dù cho nó có một số đặc điểm khác thường và dù cho các chi khác trong phân bộ có hóa thạch hoàn chỉnh hơn.

Có lẽ là giáp long đuôi chùy lớn nhất từng biết, Ankylosaurus ước tính dài từ 6 đến 8 mét (19,7 đến 26,2 ft) và nặng từ 4,8 đến 8 tấn (5,3 đến 8,8 tấn Mỹ). Đi bằng bốn chân, với một thân hình rộng, chắc nịch. Sọ thì thập, rộng, có hai sừng mọc từ phía sau đầu chĩa về phía sau và hai sừng khác dưới hai sừng này chĩa về phía sau và phía dưới. Khác với các giáp long khác, lỗ mũi của Ankylosaurus hướng về hai bên thay vì về đằng trước. Phần trước của hàm được bao trong một cái mỏ, với những hàng răng nhỏ hình lá ở phía sau. Toán thân bọc trong một lớp giáp, hay da cốt hóa, cổ thì được bao bởi nửa vòng bằng xương và cuối đuôi thì có một chùy lớn. Xương ở sọ cũng như ở các phần khác của cơ thể dính lại với nhau giúp tăng sức chịu lực tác động từ bên ngoài. Đặc điểm này là nguồn gốc của tên chi.

Ankylosaurus là thành viên của họ Giáp long đuôi chùy (Ankylosauridae). Họ hàng gần nhất của nó có lẽ là Anodontosaurus và Euoplocephalus. Ankylosaurus có lẽ là một động vật chậm chạp nhưng có thể thi triển những động tác nhanh khi cần thiết. Cái mõm rộng rộng của nó cho thấy nó là một động vật gặm không chọn lựa. Các xoang và khoang ở mũi có thể để cân bằng nhiệt và nước hoặc có thể có vai trò phát âm. Cái chùy ở cuối đuôi có lẽ được dùng để tự vệ trước kẻ thù ăn thịt hoặc để đánh nhau. Hóa thạch của Ankylosaurus đã được tìm thấy ở thành hệ Hell Creek, Lance, Scollard, Frenchman và Ferris. nhưng có vẻ như chi này hiếm thấy trong môi trường sống của nó lúc bấy giờ. Dù sống cùng với các giáp long xương kết, phạm vi và các ổ sinh thái của chúng có vẻ như không trùng nhau, và Ankylosaurus có lẽ đã sống ở những vùng đất cao. Ankylosaurus cũng sống cùng với các khủng long nhưTyrannosaurus, Triceratops và Edmontosaurus.

Sơ tả

Ankylosaurus là một trong những chi giáp long đuôi chùy lớn nhất được biết. Vào năm 2004, nhà cổ sinh người Mỹ Kenneth Carpenter ước tính chiều dài của cá thể có mẫu sọ lớn nhất hiện tại (mẫu CMN 8880, dài 64,5 cm (25,4 inch), rộng 74,5 cm (29,3 inch)) có thể đạt tới 6,25 m (20,5 foot), chiều rộng tới 1,5 m (4,9 foot) và cao 1,7 m (5,6 foot) đo tại hông. Mẫu sọ nhỏ nhất (AMNH 5214, dài 55,5 cm (21,9 inch), rộng 64,5 cm (25,4 inch)) theo Carpenter thuộc cá thể dài 5,4 m (17,7 foot) và cao khoảng 1,4 m (4,6 foot).[2] Năm 2017, dựa trên so sánh với những mẫu ankylosaurine khác hoàn chỉnh hơn, hai nhà cổ sinh người Canada Victoria Arbour và Jordan Mallon ước tính chiều dài 7,56–9,99 m (24,8–32,8 foot) cho CMN 8880 và 6,02–7,95 m (19,8–26,1 foot) cho AMNH 5214. Dù AMNH 5214 là mẫu Ankylosaurus nhỏ nhất, sọ của nó vẫn lớn hơn tất cả ankylosaurine khác. Chỉ có vài khủng long bọc giáp khác đạt đến 6 m (20 foot) chiều dài. Dựa trên quan sát thấy các đốt sống của AMNH 5214 không lớn hơn mấy so với những ankylosaurine khác, Arbour và Mallon nghĩ mức tối đa gần 10 m (33 foot) mà họ gán cho chiều dài của một Ankylosaurus to là quá lớn và ước khoảng 8 m (26 foot) là hợp lý hơn. Về khối lượng, Arbour và Mallon ước chừng 4,78 tấn (10.500 lb) cho AMNH 5214 và (một cách không chắc chắn) 7,95 tấn (17.500 lb) cho CMN 8880.[3] Benson và các đồng nghiệp năm 2014 thì ước tính 4,8 tấn (11.000 lb) cho cá thể mẫu AMNH 5214.[4]

Phần lớn bộ xương Ankylosaurus, bao gồm phần lớn khung chậu, đuôi và chân, hiện vẫn chưa được biết.[2] Ankylosaurus đi bằng bốn chân với hai chi sau dài hơn chi trước.[5] Xương vai cùng với xương quạ (đoạn xương hình chữ nhật nối với phần dưới xương vai) ở AMNH 5895 dính vào nhau và có các entheses (mô nối) để gắn cơ vào. Ở mẫu AMNH 5895, xương vai dài 61,5 cm (24,2 inch). Xương cánh tay của mẫu AMNH 5214 thì ngắn, rất rộng và dài khoảng 54 cm (21 inch). Xương đùi, cũng của mẫu AMNH 5214, rất chắc khỏe, dài khoảng 67 cm (26 inch). Dù hiện nay chưa đào thấy chân của Ankylosaurus, chân sau nó có lẽ có ba ngón, ngoại suy từ những giáp long đuôi chùy khác.[2]

The cervical vertebrae of the neck had broad neural spines that increased in height towards the body. The front part of the neural spines had well-developed entheses, which was common among adult dinosaurs, and indicates the presence of large ligaments, which helped support the massive head. The dorsal vertebrae of the back had centra (or bodies) that were short relative to their width, and their neural spines were short and narrow. The dorsal vertebrae were tightly spaced, which limited the downwards movement of the back. The neural spines had ossified (turned to bone) tendons, which also overlapped some of the vertebrae. The ribs of the last four back vertebrae were fused to them, and the ribcage was very broad in this part of the body. The ribs had scars that show where muscles attached to them. The caudal vertebrae of the tail had centra that were slightly amphicoelous, meaning they were concave on both sides.[2]

Hộp sọ

The three known Ankylosaurus skulls differ in various details; this is thought to be the result of taphonomy (changes happening during decay and fossilization of the remains) and individual variation. The skull was low and triangular in shape, and wider than it was long; the back of the skull was broad and low. The skull had a broad beak on the premaxillae. The orbits (eye sockets) were almost round to slightly oval and did not face directly sideways because the skull tapered towards the front. The braincase was short and robust, as in other ankylosaurines. Crests above the orbits merged into the upper squamosal horns (their shape has been described as "pyramidal"), which pointed backwards to the sides from the back of the skull. The crest and horn were probably separate elements originally, as seen in the related Pinacosaurus and Euoplocephalus. Below the upper horns, jugal horns were present, which pointed backward and down. The horns may have originally been osteoderms (armor plates) that fused to the skull. The scale-like pattern on the skull surface (called "caputegulae" in ankylosaurs) was the result of remodeling of the skull itself. This obliterated the sutures between skull elements, which is common for adult ankylosaurs. The scale pattern of the skull was variable between specimens, though some details are shared. Ankylosaurus had a diamond-shaped (or hexagonal) internarial scale at the front of the snout between the nostrils, two squamosal osteoderms above the orbit, and a ridge of scales at the back of the skull.[3][2][6]

The snout region of Ankylosaurus was unique among ankylosaurs, and had undergone an "extreme" transformation compared to its relatives. The snout was arched and truncated at the front, and the nostrils were elliptical and were directed downward and outward, unlike in all other known ankylosaurids where they faced obliquely forward or upward. Additionally, the nostrils were not visible from the front because the sinuses were expanded to the sides of the premaxilla bone, to a larger extent than seen in other ankylosaurs. Large loreal caputegulae—strap-like, side osteoderms of the snout—completely roofed the enlarged opening of the nostrils, giving a bulbous appearance. The nostrils also had an intranarial septum, which separated the nasal passage from the sinus. Each side of the snout had five sinuses, four of which expanded into the maxilla bone. The nasal cavities (or chambers) of Ankylosaurus were elongated and separated by a septum at the midline, which divided the inside of the snout into two mirrored halves. The septum had two openings, including the choanae (internal nostrils).[2][3]

The maxillae expanded to the sides, giving the impression of a bulge, which may have been due to the sinuses inside. The maxillae had a ridge that may have been the attachment site for fleshy cheeks; the presence of cheeks in ornithischians is controversial, but some nodosaurid ankylosaurs had armor plates that covered the cheek region, which may have been embedded in the flesh. Specimen AMNH 5214 has 34–35 dental alveoli (tooth sockets) in the maxilla and has more teeth than any other known ankylosaurid. The tooth rows in the maxillae of this specimen are about 20 cm (8 in) long. Each alveolus had a foramen (opening) near its side where a replacement tooth could be seen.[2]

Compared to other ankylosaurs, the mandible of Ankylosaurus was low in proportion to its length, and, when seen from the side, the tooth row was almost straight instead of arched. The mandibles are completely preserved only in the smallest specimen (AMNH 5214) and are about 41 cm (16 in) long. The incomplete mandible of the largest specimen (CMN 8880) is the same length. AMNH 5214 has 35 dental alveoli in the left dentary and 36 in the right, for a total of 71, the highest number known for any ankylosaurid. The predentary bone of the tip of the mandibles has not yet been found.[2] The tooth row was relatively short.[3] Like other ankylosaurs, Ankylosaurus had small, phylliform (leaf-shaped) teeth, which were compressed sideways.[7] The teeth were mostly taller than they were wide, and were very small; their size in proportion to the skull meant that the jaws could accommodate more teeth than other ankylosaurines. The teeth of the largest Ankylosaurus skull are smaller than those of the smallest skull in the absolute sense. Some teeth from behind in the tooth row curved backwards, and tooth crowns were usually flatter on one side than the other.[2] Ankylosaurus teeth are diagnostic and can be distinguished from the teeth of other ankylosaurids based on their smooth sides. The denticles were large, their number ranging from six to eight on the front part of the tooth, and five to seven behind.[2][8]

Bộ giáp

A prominent feature of Ankylosaurus was its armor, consisting of knobs and plates of bone known as osteoderms, or scutes, embedded in the skin. These have not been found in articulation, so their exact placement on the body is unknown, though inferences can be made based on related animals, and various configurations have been proposed. The osteoderms ranged from 1 cm (0,4 in) in diameter to 35,5 cm (14,0 in)[chuyển đổi: số không hợp lệ] in length, and varied in shape. The osteoderms of Ankylosaurus were generally thin walled and hollowed on the underside. Compared to Euoplocephalus, the osteoderms of Ankylosaurus were smoother. Small osteoderms and ossicles probably occupied the space between the larger ones. The osteoderms covering the body were very flat, though with a low keel at one margin. In contrast, the nodosaurid Edmontonia had high keels stretching from one margin to the other on the midline of its osteoderms. Ankylosaurus had some smaller osteoderms with a keel across the midline.[3][2]

Like other ankylosaurids, Ankylosaurus had cervical half-rings (armor plates on the neck), but these are known only from fragments, making their exact arrangement uncertain. Carpenter suggested that when seen from above, the plates would have been paired, creating an inverted V-shape across the neck, with the midline gap probably being filled with small ossicles (round bony scutes) to allow for movement. He believed the width of this armor belt was too wide to have fitted solely on the neck, and that it covered the base of the neck and continued onto the shoulder region. Arbour and Philip J. Currie disagreed with Carpenter's interpretation in 2015 and pointed out that the cervical half-ring fragments of specimen AMNH 5895 did not fit together in the way proposed by Carpenter (though this could be due to breakage). They instead suggested that the fragments represented the remains of two cervical half-rings, which formed two semi-circular plates of armor around the upper part of the neck, as in the closely related Anodontosaurus and Euoplocephalus.[2][6] Arbour and Mallon elaborated on this idea, describing the shape of these half-rings as "continuous U-shaped yokes" over the upper part of the neck, and suggested that Ankylosaurus had six keeled osteoderms with oval bases on each half-ring. Other ankylosaurids often have many smaller osteoderms surrounding these larger ones.[3]

The first osteoderms behind the second cervical half-ring would have been similar in shape to those in the half-ring, and the osteoderms on the back probably decreased in diameter hindwards. The largest osteoderms were probably arranged in transverse and longitudinal rows across most of the body, with four or five transverse rows separated by creases in the skin. The osteoderms on the flanks would probably have had a more square outline than those on the back. There may have been four longitudinal rows of osteoderms on the flanks. Unlike some basal ankylosaurs and many nodosaurs, ankylosaurids do not appear to have had co-ossified pelvic shields above their hips. Some osteoderms without keels may have been placed above the hip region of Ankylosaurus, as in Euoplocephalus. Ankylosaurus may have had three or four transverse rows of circular osteoderms over the pelvic region, which were smaller than those on the rest of the body, as in Scolosaurus. Smaller, triangular osteoderms may have been present on the sides of the pelvis. Flattened, pointed plates resemble those on the sides of the tail of Saichania. Osteoderms with oval keels could have been placed on the upper side of the tail or the side of the limbs. Compressed, triangular osteoderms found with Ankylosaurus specimens may have been placed on the sides of the pelvis or the tail. Ovoid, keeled, and teardrop-shaped osteoderms are known from Ankylosaurus, and may have been placed on the forelimbs, like those known from Pinacosaurus, but it is unknown whether the hindlimbs bore osteoderms.[2][3]

The tail club (or tail knob) of Ankylosaurus was composed of two large osteoderms, with a row of small osteoderms at the midline, and two small osteoderms at the tip; these osteoderms obscured the last tail vertebra. As only the tail club of specimen AMNH 5214 is known, the range of variation between individuals is unknown. The tail club of AMNH 5214 is 60 cm (24 in) long, 49 cm (19 in) wide, and 19 cm (7 in) tall. The club of the largest specimen may have been 57 cm (22 in) wide. The tail club of Ankylosaurus was semicircular when seen from above, similar to those of Euoplocephalus and Scolosaurus but unlike the pointed club osteoderms of Anodontosaurus or the narrow, elongated club of Dyoplosaurus. The last seven tail vertebrae formed the "handle" of the tail club. These vertebrae were in contact, with no cartilage between them, and were sometimes co-ossified, which made them immobile. Ossified tendons attached to the vertebrae in front of the tail club, and these features together helped strengthen it. The interlocked zygapophyses (articular processes) and neural spines of the handle vertebrae were U-shaped when seen from above, whereas those of most other ankylosaurids are V-shaped, which may be due to the handle of Ankylosaurus being wider. The larger width may indicate that the tail of Ankylosaurus was shorter in relation to its body length than those of other ankylosaurids, or that it had the same proportions but with a smaller club.[3][2][9]

Lịch sử khai quật

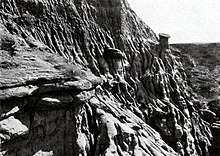

In 1906, an American Museum of Natural History expedition led by paleontologist Barnum Brown discovered the type specimen of Ankylosaurus magniventris (AMNH 5895) in the Hell Creek Formation, near Gilbert Creek, Montana. The specimen (found by collector Peter Kaisen) consisted of the upper part of a skull, two teeth, part of the shoulder girdle, cervical, dorsal, and caudal vertebrae, ribs, and more than thirty osteoderms. Brown scientifically described the animal in 1908; the genus name is derived from the Greek words αγκυλος/ankulos ('bent' or 'crooked'), referring to the medical term ankylosis, the stiffness produced by the fusion of bones in the skull and body, and σαυρος/sauros ('lizard'). The name can be translated as "fused lizard", "stiff lizard", or "curved lizard". The type species name magniventris is derived from the tiếng Latinh: magnus ('great') and tiếng Latinh: venter ('belly'), referring to the great width of the animal's body.[10][11][12]

The skeletal reconstruction accompanying the 1908 description restored the missing parts in a fashion similar to Stegosaurus, and Brown likened the result to the extinct armored mammal Glyptodon.[10] In contrast to modern depictions, Brown's stegosaur-like reconstruction showed robust forelimbs, a strongly arched back, a pelvis with prongs projecting forwards from the ilium and pubis, as well as a short, drooping tail without a tail club, which was unknown at the time. Brown also reconstructed the armor plates in parallel rows running down the back; this arrangement was purely hypothetical. Brown's reconstruction became highly influential, and restorations of the animal based on his diagram were published as late as the 1980s.[13][14][15] In a 1908 review of Brown's Ankylosaurus description, American paleontologist Samuel Wendell Williston criticised the skeletal reconstruction as being based on too few remains, and claimed that Ankylosaurus was merely a synonym of the genus Stegopelta, which Williston had named in 1905. Williston also stated that a skeletal reconstruction of the related Polacanthus by Hungarian paleontologist Franz Nopcsa was a better example of how ankylosaurs would have appeared in life.[16] The claim of synonymy was not accepted by other researchers, and the two genera are now considered distinct.[17]

Brown had collected 77 osteoderms while excavating a Tyrannosaurus specimen in the Lance Formation of Wyoming in 1900. He mentioned these osteoderms (specimen AMNH 5866) in his description of Ankylosaurus but thought they belonged to the Tyrannosaurus instead. Paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn also expressed this view when he described the Tyrannosaurus specimen as the now invalid genus Dynamosaurus in 1905. More recent examination has shown them to be similar to those of Ankylosaurus; it seems that Brown had compared them with some Euoplocephalus osteoderms, which had been erroneously catalogued as belonging to Ankylosaurus at the AMNH.[2][18]

In 1910 another AMNH expedition led by Brown discovered an Ankylosaurus specimen (AMNH 5214) in the Scollard Formation by the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada. This specimen included a complete skull, mandibles, the first and only tail club known of this genus, as well as ribs, vertebrae, limb bones, and armor. In 1947 fossil collectors Charles M. Sternberg and T. Potter Chamney collected a skull and mandible (specimen CMN 8880, formerly NMC 8880), a kilometre (0.6 mile) north of where the 1910 specimen was found. This is the largest-known Ankylosaurus skull, but it is damaged in places. A section of caudal vertebrae (specimen CCM V03) was discovered in the 1960s in the Powder River drainage, Montana, part of the Hell Creek Formation. In addition to these five incomplete specimens, many other isolated osteoderms and teeth have been found.[3][2]

In 1990 American paleontologist Walter P. Coombs pointed out that the teeth of two skulls assigned to A. magniventris differed from those of the holotype specimen in some details, and though he expressed a "considerate temptation" to name a new species of Ankylosaurus for these, he refrained from doing so, as the range of variation in the species was not completely documented. He also raised the possibility that the two teeth associated with the holotype specimen perhaps did not belong to it, as they were found in matrix within the nasal chambers.[7] Carpenter accepted the teeth as belonging to A. magniventris, and that all the specimens belonged to the same species, noting that the teeth of other ankylosaurs are highly variable.[2]

Most of the known Ankylosaurus specimens were not scientifically described at length, though several paleontologists planned to do so until Carpenter redescribed the genus in 2004. Carpenter noted that Ankylosaurus has become the archetypal member of its group, and the best-known ankylosaur in popular culture, perhaps due to a life-sized reconstruction of the animal being featured at the 1964 World's Fair in New York City.[2] That sculpture, as well as the American artist Rudolph Zallinger's 1947 mural The Age of Reptiles and other later popular depictions, showed Ankylosaurus with a tail club, following the first discovery of this feature in 1910. In spite of its familiarity, it is known from far fewer remains than its closest relatives. In 2017 Arbour and Mallon redescribed the genus in light of newer ankylosaur discoveries, including elements of the holotype that had not been previously mentioned in the literature (such as parts of the skull and the cervical half-rings). They concluded that though Ankylosaurus is iconic and the best-known member of its group, it was bizarre in comparison to related ankylosaurs, and therefore not representative of the group.[3]

Many traditional popular depictions show Ankylosaurus in a squatting posture and with a huge tail club being dragged over the ground. Modern reconstructions show the animal with a more upright limb posture and with the tail held off the ground. Likewise, large spines projecting sideways from the body (similar to those of nodosaurs) are present in many traditional depictions, but are not known from Ankylosaurus itself.[13] The armor of Ankylosaurus has often been conflated with that of Edmontonia (earlier referred to as Palaeoscincus); in addition to Ankylosaurus being depicted with spikes, Edmontonia has also been depicted with an Ankylosaurus-like tail club (a feature nodosaurids did not have), including in a mural by the American artist Charles R. Knight from 1930.[3]

Cây phân loại

Brown thấy Ankylosaurus đặc biệt đến nỗi ông tạo một họ mới tên Ankylosauridae chứa nó là chi điển hình. Các thành viên trong họ được gọi là giáp long đuôi chùy. Đặc điểm chung là có các vảy xương, hộp sọ lớn hình tam giác, cái cổ ngắn và thân mình rộng. Chi Palaeoscincus (chỉ được biết qua hóa thạch răng), và Euoplocephalus (chỉ được biết khi đó qua vảy xương và một phần hộp sọ) cũng được ông xếp vào họ này. Vì tình trạng rời rạc, chắp vá của các hóa thạch còn sót lại, Brown không thể hoàn toàn phân biệt Euoplocephalus và Ankylosaurus. Chỉ có trong tay hóa thạch không hoàn chỉnh của một vài thành viên trong họ, Brown xếp lầm họ này vào phân thứ bộ Kiếm long.[10] Năm 1923 Osborn tạo một phân thứ bộ riêng cho các giáp long đuôi chùy, lấy tên là Ankylosauria. Các thành viên trong phân thứ bộ được gọi là giáp long.[19]

Cả Giáp long lẫn Kiếm long đều nằm trong nhánh Thyreophora. Nhóm này xuất hiện lần đầu vào tầng Semur và tồn tại suốt 135 triệu năm cho đến tầng Maastrich thì biến mất. Chúng có một vùng phân bố rộng, nhan nhản khắp nơi thuộc nhiều môi trường khác nhau.[2][14] Việc tìm thấy nhiều mẫu hoàn thiện và khám phá nhiều chi mới làm các giả thuyết về cây phân loại giữa các giáp long trở nên phức tạp hơn và thường thay đổi giữa các nghiên cứu. Ngoài Ankylosauridae, Ankylosauria còn có họ Nodosauridae và, ở một số nghiên cứu, Polacanthidae.[20] Ankylosaurus nằm trong phân họ Ankylosaurinae (các thành viên trong phân họ được gọi là ankylosaurine) trong họ Ankylosauridae.[20] Ankylosaurus có vẻ có quan hệ gần gũi nhất với Anodontosaurus và Euoplocephalus về phương diện phân loại học.[21] Cây phát sinh loài dưới đây dựa trên phân tích phát sinh chủng loại phân họ Ankylosaurinae thực hiện bởi Arbour và Currie vào năm 2015:[6]

| Ankylosaurinae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Since Ankylosaurus and other Late Cretaceous North American ankylosaurids grouped with Asian genera (in a tribe the authors named Ankylosaurini), Arbour and Currie suggested that earlier North American ankylosaurids had gone extinct by the late Albian or Cenomanian ages of the Middle Cretaceous. Ankylosaurids thereafter recolonised North America from Asia during the Campanian or Turonian ages of the Late Cretaceous, and there diversified again, leading to genera such as Ankylosaurus, Anodontosaurus, and Euoplocephalus. This explains a 30-million-year gap in the fossil record of North American ankylosaurids between these ages.[6]

Cổ sinh

Thức ăn

Như những khủng long hông chim khác, Ankylosaurus là động vật ăn cỏ. Cái mõm rộng của nó thích hợp cho việc ăn bừa các loại thực vật tầng thấp,[2] dù so với một số bà con gần, đặc biệt là Euoplocephalus, nó vẫn còn kén chọn hơn.[22] Các khám phá gần đây cho thấy dù giáp long có lẽ không ăn thực vật có sợi và có gỗ, khẩu phần ăn của chúng có vẻ không chỉ có thực vật mềm như người ta nghĩ trước đây mà còn gồm lá cứng và trái có nhiều thịt.[23] Thức ăn của Ankylosaurus có khả năng là những bụi cây thấp và dương xỉ, những loại thực vật có rất nhiều thời đó. Nếu là động vật nội nhiệt thì Ankylosaurus sẽ cần khoảng 60 kg (130 lb) dương xỉ mỗi ngày, tương đương với lượng thực vật khô mà một con voi to sẽ cần. Nhu cầu dinh dưỡng này sẽ được đáp ứng tốt hơn nếu nó cũng ăn trái cây, điều mà dạng răng nhỏ, nhọn cũng như cái mõm hẹp hơn của nó (so với các giáp long đuôi chùy khác như Euoplocephalus) có vẻ thích ứng hơn. Dạng răng này cũng thích hợp cho việc ăn một số loài không xương sống nhỏ; vậy nên thi thoảng chắc nó cũng ăn loại động vật này để bổ sung dinh dưỡng.[3]

Thân răng Ankylosaurus bị mòn ở mặt thay vì đỉnh như ở giáp long xương kết.[2] Vào năm 1982, Carpenter gán cho hai mẫu răng hóa thạch rất nhỏ, dài 3,2 và 3,3mm, đào từ thành hệ Lance và Hell Creek, là của Ankylosaurus con. Qua việc mẫu 3,2mm bị mòn rất dữ, Carpenter nghĩ các giáp long đuôi chùy hoặc chí ít là con non của chúng không nuốt chửng thức ăn mà có nhai theo một cách nào đó.[8] Vì Ankylosaurus trưởng thành ít nhai, việc kiếm thức ăn của chúng sẽ chiếm thời gian trong ngày ít hơn là voi hiện đại.[3] Với lồng ngực rộng, Ankylosaurus có khả năng đã tiêu hóa các thức ăn không nhai này qua quá trình lên men chót ruột phôi, tương tự như các loài thằn lằn ăn cỏ hiện đại có nhiều khoang trong ruột già lớn.[2]

Vào năm 1969, nhà cổ sinh vật học người Áo Georg Haas nhận xét dù có hộp sọ lớn, hệ cơ ở đấy của các giáp long đuôi chùy khá là yếu. Theo ông, chuyển động hàm của chúng bị giới hạn theo chiều lên và xuống, dẫn đến ngoại suy giáp long đuôi chùy chỉ có thể ăn thực vật mềm không nhám.[24] Các nghiên cứu sau này về Euoplocephalus cho thấy chuyển động hàm về hai bên cũng như về phía trước là có thể và hộp sọ của chúng cũng có thể chịu được lực đáng kể.[25] Một nghiên cứu năm 2016 về tiếp xúc mặt nhai của các mẫu giáp long đuôi chùy cho thấy khả năng chuyển động hàm về phía sau (dật lùi) được tiến hóa một cách độc lập ở các dòng giáp long đuôi chùy khác nhau, bao gồm những chi khủng long thời Phấn trắng muộn ở Bắc Mỹ như Ankylosaurus và Euoplocephalus.[26]

Paraglossalia (phần xương/sụn hình tam giác trong lưỡi) ở một mẫu Pinacosaurus (một chi giáp long khác) cho thấy dấu hiệu của sự căng cơ, được cho là một đặc điểm phổ biến ở các giáp long. Những nhà khoa học làm việc với mẫu này nhận định khủng long bọc giáp phụ thuộc chủ yếu vào cái lưỡi chắc khỏe và xương móng-mang (xương lưỡi) của mình khi ăn, vì răng của chúng thì khá nhỏ và tốc độ thay răng cũng khá chậm. Một số loài kỳ giông hiện đại cũng có dạng xương lưỡi tương tự và lưỡi của chúng thì có thể cuộn lại để lấy thức ăn.[23] Vị trí chếch về phía sau của lỗ mũi, tương tự như ở thằn lằn giun đào hang và rắn mù, có thể là dấu chỉ cho tập tính sục đất, mặc dù Ankylosaurus có lẽ không phải là động vật đào hang. Những đặc điểm này, cộng với việc tốc độ tạo răng thấp ở các giáp long so với những khủng long hông chim khác, cho thấy Ankylosaurus có thể là động vật ăn tạp. Ankylosaurus cũng đã có lẽ (hoặc thay vào đó) thọc đầu vào đất để tìm củ và rễ cây.[3]

Airspaces and senses

In 1977 Polish paleontologist Teresa Maryańska proposed that the complex sinuses and nasal cavities of ankylosaurs may have lightened the weight of the skull, housed a nasal gland, or acted as a chamber for vocal resonance.[2][27] Carpenter rejected these hypotheses, arguing that tetrapod animals make sounds through the larynx, not the nostrils, and that reduction in weight was minimal, as the spaces only accounted for a small percent of the skull volume. He also considered a gland unlikely and noted that the sinuses may not have had any specific function.[2] It has also been suggested that the respiratory passages were used to perform a mammal-like treatment of inhaled air, based on the presence and arrangement of specialized bones.[27]

A 2011 study of the nasal passages of Euoplocephalus supported their function as a heat and water balancing system, noting the extensive blood vessel system and an increased surface area for the mucosa membrane (used for heat and water exchange in modern animals). The researchers also supported the idea of the loops acting as a resonance chamber, comparable to the elongated nasal passages of saiga antelope and the looping trachea of cranes and swans. Reconstructions of the inner ear suggest adaptation to hearing at low frequencies, such as the low-toned resonant sounds possibly produced by the nasal passages. They disputed the possibility that the looping is related to olfaction (sense of smell) as the olfactory region is pushed to the sides of the main airway.[28]

The shape of the nasal chambers of Ankylosaurus indicate that airflow was unidirectional (looping through the lungs during inhalation and exhalation), although it may also have been bidirectional in the posterior nasal chamber, with air directed past the olfactory lobes.[2] The enlarged olfactory region of ankylosaurids indicates a well-developed sense of smell,[28] and the position of the orbits of Ankylosaurus suggest some stereoscopic vision.[2] Though hindwards retraction of the nostrils is seen in aquatic animals and animals with a proboscis, it is unlikely either possibility applies to Ankylosaurus, and though the widely separated nostrils may have allowed for stereo-olfaction (where each nostril senses smells from different directions), as has been proposed for the moose, little is known about this feature.[3]

Chuyển động chi

Năm 1978, qua tái dựng hệ cơ chi trước của các giáp long, Coombs nhận định chi trước chịu phần lớn trọng lượng cơ thể và có khả năng tạo lực mạnh, có thể để lấy thức ăn. Theo Coombs, các giáp long có thể là những tay đào bới giỏi, mặc dù với cấu trúc dạng móng guốc ở bàn chân trước, hành vi này là không thường xuyên. Giáp long có thể là những động vật chậm chạp và cục mịch,[29][30] nhưng chúng có khả năng chuyển động nhanh khi cần thiết..[5]

Growth

The squamosal horns of the largest Ankylosaurus specimen are blunter than those of the smallest specimen, which is also the case in Euoplocephalus, and this may represent ontogenetic variation (related to growth development).[3] Studies of specimens of Pinacosaurus of different ages found that during ontogenetic development, the ribs of juvenile ankylosaurs fused with their vertebrae. The forelimbs strongly increased in robustness while the hindlimbs did not become larger relative to the rest of the skeleton, further evidence that the arms bore most of the weight. In the cervical half-rings, the underlying bone band developed outgrowths connecting it with the underlying osteoderms, which simultaneously fused to each other.[31] On the skull, the middle bone plates first ossified at the snout and the rear rim, with ossification gradually extending towards the middle regions. On the rest of the body, ossification progressed from the neck backward in the direction of the tail.[32]

Cách tự vệ

The osteoderms of ankylosaurids were thin in comparison to those of other ankylosaurs, and appear to have been strengthened by randomly distributed cushions of collagen fibers. Structurally similar to Sharpey's fibres, they were embedded directly into the bone tissue, a feature unique to ankylosaurids. This would have provided the ankylosaurids with an armor covering that was both lightweight and highly durable, being resistant to breakage and penetration by the teeth of predators.[33] The palpebral bones over the eyes may have provided additional protection for them.[34] Carpenter suggested in 1982 that the heavily vascularized armor may also have had a role in thermoregulation as in modern crocodilians.[35]

The tail club of Ankylosaurus seems to have been an active defensive weapon, capable of producing enough of an impact to break the bones of an assailant. The tendons of the tail were partially ossified and were not very elastic, allowing great force to be transmitted to the club when it was used as a weapon.[2] Coombs suggested in 1979 that several hindlimb muscles would have controlled the swinging of the tail, and that violent thrusts of the club would have been able to break the metatarsal bones of large theropods.[30] A 2009 study estimated that ankylosaurids could swing their tails at 100 degrees laterally, and the mainly cancellous clubs would have had a lowered moment of inertia and been effective weapons. The study also found that while adult ankylosaurid tail clubs were capable of breaking bones, those of juveniles were not. Despite the feasibility of tail-swinging, the researchers could not determine whether ankylosaurids used their clubs for defense against potential predators, in intraspecific combat, or both.[36]

In 1993 Tony Thulborn proposed that the tail club of ankylosaurids primarily acted as a decoy for the head, as he thought the tail too short and inflexible to have an effective reach; the "dummy head" would lure a predator close to the tail, where it could be struck.[37] Carpenter has rejected this idea, as tail club shape is highly variable among ankylosaurids, even in the same genus.[2]

Cổ sinh thái

Tồn tại vào giai đoạn cuối của kỷ Phấn trắng: tầng Maastricht (khoảng 68 đến 66 triệu năm trước đây), Ankylosaurus là một trong những chi khủng long cuối cùng trên Trái Đất trước khị sự kiện tuyệt chủng kỷ Phấn trắng-đệ Tam xảy ra. Vết tích còn sót lại của Ankylosaurus (mẫu gốc trong thành hệ Hell Creek, Montana; các mẫu khác thuộc thành hệ Lance, Ferris, Wyoming, thành hệ Scollard, Alberta và thành hệ Frenchman, Saskatchewan) đều có niên đại cuối kỷ Phấn trắng.[3][38][39] Cách phân bố những hóa thạch này cũng như việc hiếm khi tìm thấy chúng trong lớp trầm tích của các thành hệ kể trên (dù xương dễ hóa thạch hơn ở khu vực này) cho thấy Ankylosaurus có vẻ thích sống ở vùng đất cao hơn là những vùng duyên hải thấp. Cũng có thể về phương diện sinh thái, Ankylosaurus là một chi hiếm gặp. Trong các thành hệ kể trên, người ta còn tìm thấy một giống khủng long bọc giáp khác, một loại giáp long xương kết tạm gán tên là Edmontonia sp. Theo Carpenter, vùng phân bố của nó không trùng với Ankylosaurus. Cho đến nay, chưa tìm thấy hóa thạch nào của hai chi này mà nằm tương đối gần nhau. So với Ankylosaurus, giống Edmontonia sp. này có vẻ thích sống ở những nơi đất thấp. Ngoài ra, cái mõm hẹp hơn cho thấy nó có một khẩu phần ăn kén hơn Ankylosaurus, càng củng cố cho giả thuyết phân chia tổ sinh thái, bất kể vùng phân bố hai chi có trùng hay không.[2][3]

Với trọng tâm cơ thể thấp, Ankylosaurus không có khả năng đốn cây như ở voi hiện đại. Nó cũng như không thể tuốt và nhai vỏ cây. Đặc điểm này cùng với việc khi trưởng thành chúng không tụ tập thành nhóm (dù một số khủng long bọc giáp có tụ tập với nhau khi chúng còn non) cho thấy Ankylosaurus ít có khả năng thay đổi diện mạo của hệ sinh thái mà nó đang sống theo kiểu voi hiện đại làm, dù nó cũng là một động vật lớn ăn thực vật với nhu cầu dinh dưỡng tương đương. Thay vào đấy, vai trò "kỹ sư hệ sinh thái" kiểu như vậy được đảm nhiệm bởi các khủng long mỏ vịt.[3]

Từ giữa cho đến cuối kỷ Phấn trắng, Bắc Mỹ bị ra làm hai bởi vùng biển nội hải Western Interior: Laramidia ở phía Tây và Appalachia ở phía Đông. Các thành hệ Hell Creek, Lance và Scollard thuộc bờ Tây của đường biển này. Đây là một vùng đồng bằng duyên hải rộng lớn, trải dài từ ven biển cho tới dãy núi Rocky mới hình thành. Đá bùn và sa thạch là thành phần chủ yếu, kết quả của môi sinh bãi bồi.[40][41][42] Vùng mà Ankylosaurus và các chi khủng long bọc giáp kỷ Phấn Trắng muộn khác được tìm thấy có khí hậu ôn đới/cận nhiệt gió mùa, thi thoảng có mưa, bão nhiệt đới và cháy rừng.[26] Thành hệ Hell Creek có nhiều loại thực vật phát triển, chủ yếu là thực vật có hoa, xen lẫn là các loại thực vật ngành thông, dương xỉ và thực vật lớp tuế. Sự giàu có về hóa thạch lá tại hàng tá vị trí khác nhau cho thấy khu vực này được phủ phần lớn bởi cây nhỏ.[43] Ankylosaurus sống cạnh nhiều loại khủng long như khủng long sừng Triceratops, Torosaurus, thescelosaurid Thescelosaurus, khủng long mỏ vịt Edmontosaurus, khủng long đầu dày Pachycephalosaurus, khủng long chân thú Struthiomimus, Ornithomimus, Troodon, Tyrannosaurus cùng một giống giáp long xương kết chưa xác định khác.[39][44]

Xem thêm

Phương tiện

Dữ liệu liên quan tới Ankylosaurus tại Wikispecies

Dữ liệu liên quan tới Ankylosaurus tại Wikispecies Tư liệu liên quan tới Ankylosaurus tại Wikimedia Commons

Tư liệu liên quan tới Ankylosaurus tại Wikimedia Commons

Chú thích

Ghi chú

Trích dẫn

- ^ “Ankylosaurus”. Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Carpenter, K. (2004). “Redescription of Ankylosaurus magniventris Brown 1908 (Ankylosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Western Interior of North America”. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 41 (8): 961–86. Bibcode:2004CaJES..41..961C. doi:10.1139/e04-043.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Arbour, V.M.; Mallon, J.C. (2017). “Unusual cranial and postcranial anatomy in the archetypal ankylosaur Ankylosaurus magniventris”. FACETS. 2 (2): 764–794. doi:10.1139/facets-2017-0063.

- ^ Benson, R. B. J.; Campione, N. E.; Carrano, M. T.; Mannion, P. D.; Sullivan, C.; Evans, D. C.; và đồng nghiệp (2014). “Rates of Dinosaur Body Mass Evolution Indicate 170 Million Years of Sustained Ecological Innovation on the Avian Stem Lineage”. PLoS Biol. 12 (5): e1001853. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853. PMC 4011683. PMID 24802911. Đã bỏ qua tham số không rõ

|displayauthors=(gợi ý|display-authors=) (trợ giúp); “Và đồng nghiệp” được ghi trong:|first5=(trợ giúp); “Và đồng nghiệp” được ghi trong:|author6=(trợ giúp) - ^ a b Coombs, W. P. (1978). “Theoretical aspects of cursorial adaptations in dinosaurs”. The Quarterly Review of Biology. 53 (4): 393–418. doi:10.1086/410790.

- ^ a b c d Arbour, V. M.; Currie, P. J. (2015). “Systematics, phylogeny and palaeobiogeography of the ankylosaurid dinosaurs”. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 14 (5): 1–60. doi:10.1080/14772019.2015.1059985.

- ^ a b Coombs, W. (1990). “Teeth and taxonomy in ankylosaurs”. Dinosaur systematics: Approaches and perspectives. Cambridge University Press. tr. 269–79. ISBN 978-0-521-43810-0. Đã bỏ qua tham số không rõ

|editors=(gợi ý|editor=) (trợ giúp) - ^ a b Carpenter, K. (1982). “Baby dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous Lance and Hell Creek formations and a description of a new species of theropod”. Rocky Mountain Geology. 20 (2): 123–134.

- ^ Arbour, V. M.; Currie, P. J. (2015). “Ankylosaurid dinosaur tail clubs evolved through stepwise acquisition of key features”. Journal of Anatomy. 227 (4): 514–23. doi:10.1111/joa.12363. PMC 4580109. PMID 26332595.

- ^ a b c Brown, B. (1908). “The Ankylosauridae, a new family of armored dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous”. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 24: 187–201. hdl:2246/1435.

- ^ Creisler, B. (7 tháng 7 năm 2003). “Dinosauria Translation and Pronunciation Guide A”. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 18 tháng 8 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 3 tháng 9 năm 2010. Đã bỏ qua tham số không rõ

|deadurl=(gợi ý|url-status=) (trợ giúp) - ^ Liddell, H. G.; Scott, R. (1980) [1871]. A Greek-English Lexicon . Oxford University Press. tr. 5. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ^ a b Glut, D. F. (1997). “Ankylosaurus”. Dinosaurs, the encyclopedia. McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers. tr. 141–143. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- ^ a b Coombs, W. (1978). “The families of the ornithischian dinosaur order Ankylosauria” (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 21 (1): 143–170.

- ^ Naish, D. (2009). The Great Dinosaur Discoveries. London: A & C Black Publishers LTD. tr. 58–59. ISBN 978-1408119068.

- ^ Williston, S. W. (1908). “Review: The Ankylosauridae”. The American Naturalist. 42 (501): 629–30. doi:10.1086/278987. JSTOR 2455817.

- ^ Carpenter, K. (2001). “Chapter 21: Phylogenetic Analysis of the Ankylosauria”. Trong Carpenter, K. (biên tập). The Armored Dinosaurs. tr. 454–83. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

- ^ Osborn, H. F. (1905). “Tyrannosaurus and other Cretaceous carnivorous dinosaurs”. Bulletin of the AMNH. American Museum of Natural History. 21 (14): 259–265. hdl:2246/1464.

- ^ Osborn, H. F. (1923). “Two Lower Cretaceous dinosaurs of Mongolia”. American Museum Novitates. 95: 1–10. hdl:2246/3267.

- ^ a b Thompson, R. S.; Parish, J. C.; Maidment, S. C. R.; Barrett, P. M. (2012). “Phylogeny of the ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)”. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 301–312. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.569091. Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>không hợp lệ: tên “thompson” được định rõ nhiều lần, mỗi lần có nội dung khác - ^ Arbour, V.M.; Currie, P.J.; Badamgarav, D. (2014). “The ankylosaurid dinosaurs of the Upper Cretaceous Baruungoyot and Nemegt formations of Mongolia”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 172 (3): 631–652. doi:10.1111/zoj.12185.

- ^ Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>sai; không có nội dung trong thẻ ref có tênŐsi2 - ^ a b Hill, R. V.; D'Emic, M. D.; Bever, G. S.; Norell, M. A. (2015). “A complex hyobranchial apparatus in a Cretaceous dinosaur and the antiquity of avian paraglossalia”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 175 (4): 892–909. doi:10.1111/zoj.12293.

- ^ Haas, G. (1969). “On the jaw musculature of ankylosaurs”. American Museum Novitates. 2399: 1–11. hdl:2246/2609.

- ^ Rybczynski, N.; Vickaryous, M. K. (2001). “Chapter 14: Evidence of Complex Jaw Movement in the Late Cretaceous Ankylosaurid, Euoplocephalus tutus (Dinosauria: Thyreophora)”. Trong K. Carpenter (biên tập). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. tr. 299–317. ISBN 978-0-253-33964-5. Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>không hợp lệ: tên “Rybzynski2001” được định rõ nhiều lần, mỗi lần có nội dung khác - ^ a b Ősi, A.; Prondvai, E.; Mallon, J.; Bodor, E. R. (2016). “Diversity and convergences in the evolution of feeding adaptations in ankylosaurs (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)”. Historical Biology. 29 (4): 1–32. doi:10.1080/08912963.2016.1208194.

- ^ a b Maryanska, T. (1977). “Ankylosauridae (Dinosauria) from Mongolia” (PDF). Palaeontologia polonica. 37: 85–151.

- ^ a b Miyashita, T., Arbour V. M.; Witmer L. M.; Currie, P. J. (2011). “The internal cranial morphology of an armoured dinosaur Euoplocephalus corroborated by X-ray computed tomographic reconstruction” (PDF). Journal of Anatomy. 219 (6): 661–75. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01427.x. PMC 3237876. PMID 21954840. Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 24 tháng 9 năm 2015. Đã bỏ qua tham số không rõ

|deadurl=(gợi ý|url-status=) (trợ giúp)Quản lý CS1: sử dụng tham số tác giả (liên kết) - ^ Coombs, W. (1978). “Forelimb muscles of the Ankylosauria (Reptilia, Ornithischia)”. Journal of Paleontology. 52 (3): 642–57. JSTOR 1303969.

- ^ a b Coombs, W. (1979). “Osteology and myology of the hindlimb in the Ankylosauria (Reptillia, Ornithischia)”. Journal of Paleontology. 53 (3): 666–84. JSTOR 1304004.

- ^ Burns, M; Tumanova, T; Currie, P (2015). “Postcrania of juvenile Pinacosaurus grangeri (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Alagteeg Formation, Alag Teeg, Mongolia: implications for ontogenetic allometry in ankylosaurs”. Journal of Paleontology. 89 (1): 168–182. doi:10.1017/jpa.2014.14.

- ^ Currie, P. J.; Badamgarav, D.; Koppelhus, E. B.; Sissons, R.; Vickaryous, M. K. (2011). “Hands, feet, and behaviour in Pinacosaurus (Dinosauria: Ankylosauridae)”. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (3): 489–504. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0055.

- ^ Scheyer, T. M.; Sander, P. M. (2004). “Histology of ankylosaur osteoderms: implications for systematics and function”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (4): 874–93. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0874:hoaoif]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4524782.

- ^ Coombs W. (1972). “The Bony Eyelid of Euoplocephalus (Reptilia, Ornithischia)”. Journal of Paleontology. 46 (5): 637–50. JSTOR 1303019..

- ^ Carpenter, K. (1982). “Skeletal and dermal armor reconstruction of Euoplocephalus tutus (Ornithischia: Ankylosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous Oldman Formation of Alberta”. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 19 (4): 689–97. Bibcode:1982CaJES..19..689C. doi:10.1139/e82-058.

- ^ Arbour, V. M. (2009). “Estimating impact forces of tail club strikes by ankylosaurid dinosaurs”. PLoS ONE. 4 (8): e6738. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.6738A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006738. PMC 2726940. PMID 19707581.

- ^ Thulborn, T. (1993). “Mimicry in ankylosaurid dinosaurs”. Record of the South Australian Museum. 27: 151–58.

- ^ Vickaryous, M. K., Maryanska, T.; Weishampel, D. B. (2004). “Ankylosauria”. Trong Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (biên tập). The Dinosauria. University of California Press. tr. 363–92. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.Quản lý CS1: sử dụng tham số tác giả (liên kết)

- ^ a b Weishampel, D. B.; Barrett, P. M.; Coria, R. A.; Le Loeuff, J.; Xu X.; Zhao X.; Sahni, A.; Gomani, E. M. P.; Noto, C. R. (2004). “Dinosaur Distribution”. Trong Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmolska, H.. (biên tập). The Dinosauria (2nd). University of California Press. tr. 517–606. ISBN 0-520-24209-2. Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>không hợp lệ: tên “WETAL04” được định rõ nhiều lần, mỗi lần có nội dung khác - ^ Lofgren, D. F. (1997). “Hell Creek Formation”. Trong Currie, P.J.; Padian, K. (biên tập). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. tr. 302–03. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6. Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>không hợp lệ: tên “lofgren1997” được định rõ nhiều lần, mỗi lần có nội dung khác - ^ Breithaupt, B. H. (1997). “Lance Formation"”. The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. tr. 394–95. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6. Đã bỏ qua tham số không rõ

|editors=(gợi ý|editor=) (trợ giúp) Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ<ref>không hợp lệ: tên “breithaupt1997” được định rõ nhiều lần, mỗi lần có nội dung khác - ^ Eberth, D. A. (1997). “Edmonton Group”. Trong Currie, P. J.; Padian, K. (biên tập). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. tr. 199–204. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6. Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>không hợp lệ: tên “eberth1997” được định rõ nhiều lần, mỗi lần có nội dung khác - ^ Johnson, K. R. (1997). “Hell Creek Flora”. Trong Currie, P. J.; Padian, K. (biên tập). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. tr. 300–02. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6. Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>không hợp lệ: tên “johnson1997” được định rõ nhiều lần, mỗi lần có nội dung khác - ^ Bigelow, P. “Cretaceous 'Hell Creek Faunal Facies'; Late Maastrichtian”. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 17 tháng 1 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 3 năm 2014. Đã bỏ qua tham số không rõ

|deadurl=(gợi ý|url-status=) (trợ giúp) Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ<ref>không hợp lệ: tên “HCFF” được định rõ nhiều lần, mỗi lần có nội dung khác