Khác biệt giữa bản sửa đổi của “Tự tử ở Hàn Quốc”

Thêm trang mới Thẻ: Người dùng thiếu kinh nghiệm thêm nội dung lớn Sửa đổi di động Sửa đổi từ trang di động |

(Không có sự khác biệt)

|

Phiên bản lúc 16:11, ngày 25 tháng 4 năm 2023

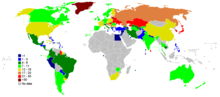

Tự tử ở Hàn Quốc xảy ra với tỷ lệ cao thứ 12 trên thế giới. Hàn Quốc có tỷ lệ tự tử cao nhất trong OECD. Năm 2012, tự tử là nguyên nhân gây tử vong cao thứ tư.

Hàn Quốc xếp thứ 12 thế giới về tỉ lệ tử tử và thứ nhất trong số các nước OECD[2][3][4]. Năm 2012, tự tử là nguyên nhân gây tử vong thứ tư ở Hàn Quốc.[5]

Tỷ lệ tự tử cao của Hàn Quốc so với các quốc gia khác trong thế giới phát triển đang trở nên trầm trọng hơn bởi tỷ lệ tự tử ở người cao tuổi. Một yếu tố khiến người cao tuổi Hàn Quốc tự tử là do tình trạng nghèo đói phổ biến ở người cao tuổi ở Hàn Quốc, với gần một nửa dân số cao tuổi của đất nước sống dưới mức nghèo khổ. Kết hợp với mạng lưới an sinh xã hội dành cho người già được tài trợ kém, điều này có thể khiến họ tự tử để tránh là gánh nặng tài chính cho gia đình họ, vì cấu trúc xã hội cũ nơi con cái chăm sóc cha mẹ phần lớn đã biến mất trong thế kỷ 21[6][7]. Kết quả là những người sống ở khu vực nông thôn có xu hướng tự tử cao hơn. Điều này là do tỷ lệ phân biệt đối xử với người cao tuổi rất cao, đặc biệt là khi đi xin việc, với 85,7% những người ở độ tuổi 50 bị phân biệt đối xử[8]. Phân biệt tuổi tác cũng liên quan trực tiếp đến tự tử, ngoài việc ảnh hưởng đến tỷ lệ nghèo đói[9]. Tự tử là nguyên nhân số một gây tử vong ở người Hàn Quốc từ 10 đến 39 tuổi.[10][11]

Tuy nhiên, những nỗ lực chủ động của chính phủ nhằm giảm tỷ lệ này đã cho thấy hiệu quả trong năm 2014, khi có 27,3 vụ tự tử trên 100.000 người, giảm 4,1% so với năm trước (28,5 người) và thấp nhất trong sáu năm kể từ mức 26,0 người của năm 2008.[12][13]

Thống kế

Độ tuổi

Tỷ lệ tự tử rất cao ở người cao tuổi là một yếu tố góp phần chính vào tỷ lệ tự tử chung của Hàn Quốc. Khi mọi người già đi, một số yếu tố tâm lý xã hội như giảm thu nhập do nghỉ hưu, tăng chi phí y tế, suy giảm hoặc khuyết tật về thể chất, mất vợ/chồng hoặc bạn bè và sống không mục đích làm tăng nguy cơ tự tử.[14] Nhiều người già nghèo khó tự sát để không trở thành gánh nặng cho gia đình, vì hệ thống phúc lợi của Hàn Quốc kém[7] và truyền thống con cái chăm sóc cha mẹ già đã phần lớn biến mất trong thế kỷ 21[6]. Kết quả là những người sống ở khu vực nông thôn có tỷ lệ tự tử cao hơn.

Mặc dù thấp hơn so với tỷ lệ ở người cao tuổi, nhưng học sinh tiểu học và đại học ở Hàn Quốc có tỷ lệ tự tử cao hơn mức trung bình.[15]

Trong 5 năm qua, số vụ tự tử hoặc tự gây thương tích đã tăng từ 4.947 vụ năm 2015 lên 9.828 vụ vào năm 2019 và hầu hết các vụ liên quan đến người trong độ tuổi từ 9 đến 24. Kang Byung-won, một thành viên Quốc hội của đảng Dân chủ tuyên bố rằng "26,9 thanh niên Hàn Quốc cố gắng tự tử hoặc tự gây thương tích mỗi ngày."

Mặc dù thấp hơn so với tỷ lệ dành cho người cao tuổi, nhưng học sinh tiểu học và đại học ở Hàn Quốc có tỷ lệ tự tử cao hơn mức trung bình.

Trong 5 năm qua, số vụ tự tử hoặc tự gây thương tích đã tăng từ 4.947 vụ năm 2015 lên 9.828 vụ vào năm 2019 và hầu hết các vụ liên quan đến người trong độ tuổi từ 9 đến 24. Kang Byung-won, một thành viên Quốc hội của đảng Dân chủ tuyên bố rằng "26,9 thanh niên Hàn Quốc cố gắng tự tử hoặc tự gây thương tích mỗi ngày."[16]

Giới tính

Trung bình, đàn ông có tỷ lệ chết vì tự tử cao gấp đôi phụ nữ[13]. Tuy nhiên, tỷ lệ thực hiện tự sát ở phụ nữ cao hơn nam giới[15]. Theo một nghiên cứu, vì nam giới sử dụng các phương pháp tự sát nghiêm trọng và nguy hiểm hơn nên nam giới có tỷ lệ tự tử thành công cao hơn nữ giới. Thang đánh giá rủi ro-giải cứu (RRRS), đo lường mức độ gây chết người của phương pháp tự sát bằng cách đánh giá tỷ lệ giữa năm yếu tố rủi ro và năm yếu tố giải cứu, trung bình là 37,18 đối với nam và 34,00 đối với nữ[17][18].

So với các quốc gia OECD khác, tỷ lệ tự tử của phụ nữ ở Hàn Quốc cao nhất với 15,0 người chết do tự tử trên mỗi 100.000 người chết, trong khi tỷ lệ tự tử của nam giới cao thứ ba với 32,5 trên 100.000 người chết. Phụ nữ cũng có tỷ lệ tự tử theo tỷ lệ tăng cao hơn so với nam giới từ năm 1986 đến năm 2005. Nam giới tăng 244%, trong khi nữ giới tăng 282%.[19]

Tình trạng hôn nhân

Các nghiên cứu cho rằng tình trạng hôn nhân khác nhau có tỷ lệ tự tử khác nhau. Những người chưa từng kết hôn hoặc thay đổi tình trạng hôn nhân do ly hôn, ly thân, góa chồng, góa vợ có nguy cơ tự tử cao hơn những người trong cuộc hôn nhân[14]. Những người đã ly hôn là nhóm có nguy cơ cao nhất, tiếp theo là những người chưa từng kết hôn và những người góa chồng/vợ là nhóm có nguy cơ thấp nhấ[14]t. Các mối quan hệ gia đình cũng góp phần vào sức khỏe tinh thần của đàn ông và phụ nữ. Nghiên cứu về tình trạng ly hôn, ly thân hoặc góa bụa cho thấy những cá nhân không hài lòng với các mối quan hệ gia đình có nguy cơ cao bị trầm cảm, có ý định tự tử và lòng tự tôn thấp.[20]

Điều kiện kinh tế xã hội

Socioeconomic status is measured by a population's level of education, degree of urbanity and deprivation of the residence. Low socioeconomic status, high stress, inadequate sleep, alcohol use, and smoking are associated with suicidal tendencies among adolescents. The economic hardship factor is noted as the most frequently referred cause for elderly suicides. As 71.4% of the elderly population is uneducated and 37.1% of them live in rural areas, they are more likely to face economic hardship, which can lead to health problems and family conflicts. All these factors together lead to an increase in suicidal ideation and completion.

Tình trạng kinh tế xã hội được đánh giá bằng trình độ học vấn của, mức độ đô thị và tình trạng thiếu nơi cư trú[21]. Tình trạng kinh tế xã hội thấp, căng thẳng cao, ngủ không đủ giấc, uống rượu và hút thuốc có liên quan đến xu hướng tự tử ở thanh thiếu niên[22]. Yếu tố khó khăn về kinh tế được ghi nhận là nguyên nhân thường được nhắc đến nhất dẫn đến các vụ tự tử ở người cao tuổi. Do 71,4% người cao tuổi không được đi học và 37,1% trong số họ sống ở nông thôn nên họ có nhiều khả năng gặp khó khăn về kinh tế, dẫn đến các vấn đề về sức khỏe và xung đột gia đình[21]. Tất cả những yếu tố này cùng nhau dẫn đến sự gia tăng ý định tự sát và tự sát thành công[21].

Vùng miền

Gangwon có tỷ lệ tự tử cao hơn 37,84% so với tỷ lệ của toàn Hàn Quốc[23]. Theo sau Gangwon, Chungnam xếp thứ hai và Jeonbuk xếp thứ ba[23]. Ulsan, Gangwon và Incheon có tỷ lệ tự tử cao nhất đối với những người trên 65 tuổi[23]. Daegu có tỷ lệ tự tử cao nhất đối với những người từ 40 đến 59 tuổi[23]. Gangwon, Jeonnam và Chungnam có tỷ lệ tự tử cao nhất đối với những người từ 20 đến 39 tuổi.[23]

Cách thức

Because South Korean law heavily restricts firearms possession, only one-third of South Korean women use violent methods to die by suicide. Poisoning is the most commonly used method for South Korean women, with pesticides accounting for half of suicide deaths among that population. 58.3% of suicides from 1996 to 2005 used pesticide poisoning. Another prevalent method by which South Koreans die by suicide is hanging. A study by Jeon et al. has shown a difference between the methods used by suicide attempters who did plan and did not plan their attempts. Unplanned suicide attempters tend to use chemical agents or falling three times as often as planned suicide attempters.

Do luật pháp Hàn Quốc hạn chế rất nhiều việc sở hữu súng nên chỉ 1/3 phụ nữ Hàn Quốc sử dụng các biện pháp bạo lực để tự tử. Dùng chất độc độc là phương pháp được sử dụng phổ biến nhất đối với phụ nữ Hàn Quốc, với thuốc trừ sâu chiếm một nửa số ca tử vong trong số đó[24]. 58,3% số vụ tự sát từ 1996 đến 2005 do ngộ độc thuốc trừ sâu[25]. Một phương pháp phổ biến khác mà người Hàn Quốc tự sát là treo cổ[26]. Một nghiên cứu của Jeon et al. đã chỉ ra sự khác biệt giữa các phương pháp mà những người có ý định tự tử sử dụng, những người đã lên kế hoạch và không lên kế hoạch cho việc tự tử. Những người cố tự tử không có kế hoạch thưởng có xu hướng sử dụng các tác nhân hóa học hoặc nhảy lầu/cầu cao hơn ba lần so với những người ý định tự tử có kế hoạch[27].

Một nghiên cứu của Subin Park et al. nói rằng một lý do chính dẫn đến xu hướng tăng chung về tỷ lệ tự tử ở Hàn Quốc từ năm 2000 đến năm 2011 là sự gia tăng các vụ tự tử bằng cách treo cổ. Trong suốt khoảng thời gian đó, treo cổ ngày càng được coi là không gây đau đớn, được xã hội chấp nhận và dễ tiếp cận, và do đó trở thành một phương pháp phổ biến hơn nhiều trong suốt thập kỷ đầu tiên của thế kỷ 21.[28]

Đầu độc Carbon monoxide

Trong những năm gần đây, trong bối cảnh tỷ lệ tự tử gia tăng, đốt than tổ ong đã được sử dụng như một phương pháp tự sát bằng cách đầu độc khí carbon monoxide.[29]

Nhảy cầu

Nhảy cầu cũng đã được sử dụng như một cách tự sát. Cầu Mapo ở Seoul, được coi là cây cầu tự sát[30][31], người dân địa phương gọi là "Cầu tự sát" và "Cây cầu tử thần"[32][33][34][35][36][37][38]. Các nhà chức trách Hàn Quốc đã cố gắng ngăn điều này bằng cách gọi cây cầu là "Cây cầu của sự sống" và dán những thông điệp trấn an trên thành cầu.[39]

Nguyên nhân

Truyền thông

According to the Werther effect, some people attempt suicide as a reaction to another suicide. This applies also for South Korea.[40] According to a study, South Korea experiences a surge in suicides after the deaths of celebrities.[41] The study has found three out of eleven cases of celebrity suicide resulted in a higher suicide rate of the population.[41] The study controlled for the potential effects of confounding factors, such as seasonality and unemployment rates, and yet celebrity suicides still had a strong correlation to increased rate of suicide rates for nine weeks.[41] The degree of media coverage of celebrity suicides impacts the degree of increase of suicide rates. In the study, the three celebrity suicides that received wide media coverage led to a surge in suicide rates, and the other celebrity suicides with low media coverage did not lead to an increase in the suicide rate.[41] In addition to the increased suicidal ideation, celebrity suicides lead people to use the same methods to attempt suicide.[42] Following actress Lee Eun-ju's death in 2005, more people used the same method of hanging.[42]

An ongoing study has also suggested that high use of the Internet is associated with suicides.[43] Among 1,573 high school students, 1.6% of the population suffered from Internet addiction and 38.0% had a risk of Internet addiction.[43] The students with, or at risk of, Internet addiction had a higher rate of suicidal ideation compared to those without Internet addiction.[43] However, the correlational nature of the study makes it difficult to determine the causal direction of this relationship.

Gia đình

Many people have been left orphaned or have lost a parent due to the Korean War. Within a random group of 12,532 adults, 18.6% of the respondents have lost their biological parent(s), with maternal death having a bigger impact on the rate of suicide attempts than paternal death.[44] A study has shown that men have the highest rate of suicide attempts when they experience maternal death from the ages of 0–4 and 5–9. Women have the highest suicide attempt rate when they experience maternal death from the ages of 5–9.[44]

Kinh tế

In 1997 and 1998, the 1997 Asian financial crisis hit South Korea.[45] During and after the economic recession of 1998, South Korea experienced a sharp economic recession of −6.9% and a surge of unemployment rate of 7.0%.[45] A study has shown that this economic downfall had a strong correlation with an increase in suicide rates.[45] Increase in unemployment and higher divorce rate during the economic downturn lead to clinical depression, which is a common factor that leads to suicide.[45] Moreover, according to Durkheim, economic downfall disturbs the social standing of an individual, meaning that the individual's demands and expectations can no longer be met. Thus, a person who cannot readjust to the deprived social order caused by economic downfall is more likely to die by suicide.[45]

Analyzing the suicides up to 2003, Park and Lester[46] note that unemployment is a major factor of high suicide rate. In South Korea, it has been the traditional duty of children to take care of their parents.[46] However, as "cultural tradition of filial obligation is not congruent with the increasingly competitive, specialized labor market of the modern era", the elderly are sacrificing themselves by suicide so as to lessen the burden on their children.[46]

Giáo dục

In South Korea, every student is obligated to take the College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT). On this day, underclassmen gather and cheer on their seniors as they enter the school to take their exams. The government has also mandated forbidding planes from flying during this time to make sure there are no distractions to these students.[47]

Education in South Korea is extremely competitive, making it difficult to get into an esteemed university. A South Korean student's school year lasts from March to February. The year divides into two semesters: one from March until July, and another from August to February. The average South Korean high school student also spends roughly 16 hours a day on school and school-related activities. They attend after school programs called hagwons and there are over 100,000 of them throughout South Korea, making them a 20 billion dollar industry.[48] Again, this is because of the competitiveness of acceptance into a good university. Most South Korean test scores are also graded on a curve, leading to more competition. Since 2012, students in South Korea go to school from Monday to Friday. Before 2005, South Korean students went to school every day from Monday to Saturday.

Although South Korean education consistently ranks near the top in international academic assessments such as PISA,[22] the enormous stress and pressure[49] on its students is considered by many to constitute child abuse.[50][51] It has been blamed for high suicide rates in South Korea among those aged 10–19.[52] Studies have shown that 46% of high school students in Seoul, South Korea are depressed due to academic stress, which leads to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.[53] South Korea's competitive educational system and the stressful academic environment, plus the social expectations requiring students to excel in academics have negatively affected the physical, mental and emotional wellbeing of the students.[53]

Bệnh lý tâm thần

In South Korea, mental illness is taboo, even within a family. Over 90% of suicide victims could be diagnosed with a mental disorder, but only 15% of them received proper treatment. Over two million people suffer from depression annually in South Korea, but only 15,000 choose to receive regular treatment. Because mental illnesses are looked down upon in Korean society, families often discourage those with mental illnesses from seeking treatment.[54] Since there is such a strong negative stigma on the treatment of mental illnesses, many symptoms go unnoticed and can lead to many irrational decisions including suicide. Additionally, alcohol is often used to self-medicate, and a significant percentage of attempted suicides occur while drunk.[55]

COVID-19

As the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea continued, many men in their 50s and women in their 20s struggled, which led some to die by suicide.[56]

Phản ứng

South Korea has implemented the Strategies to Prevent Suicide (STOPS), a project whose "initiatives aimed at increasing public awareness, improving media reporting of suicide, screening for persons at high risk of suicide, restricting access to means, and improving treatment of suicidally depressed patients". All of these methods strive to increase public awareness and governmental support for suicide prevention. Currently, South Korea and other countries that have implemented this initiative are in the process of evaluating how much influence this initiative has on the suicide rate.[57] The education ministry created a smartphone app to check students' social media posts, messages and web searches for words related to suicide.[58]

Because the media coverage and portrayal of suicide influence the suicide rate, the government has "promulgated national guidelines for reporting on suicide in print media". The national guideline helps the media coverage to focus more on warning signs and possibilities of treatment, rather than factors that lead to suicide.[57]

Another method that South Korea has implemented is educating gatekeepers.[57] The gatekeeper education primarily consists of knowledge of suicide and dealing with suicidal individuals, and this education is provided to teachers, social workers, volunteers and youth leaders.[57] The South Korean government educates gatekeepers within at-risk communities, such as female elders or low-income families. To maximize the effect of gatekeepers, the government has also implemented evaluation programs to report the results.[57]

Physical measures are also taken to prevent suicide. The government has reduced "access to lethal means of self-harm". As mentioned above in the methods, the government has reduced access to poisoning agents, monoxide from charcoal, and finally train platforms. This helps to decrease impulsive suicidal behavior.[57]

Tham khảo

- ^ Värnik, Peeter (2012). “Suicide in the World”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 9 (3): 760–771. doi:10.3390/ijerph9030760. PMC 3367275. PMID 22690161.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: “Why South Korea has high suicide rates”. YouTube.

- ^ “Suicide rates, age standardized - Data by country”. World Health Organization. 2015. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 18 tháng 10 năm 2017. Truy cập ngày 13 tháng 4 năm 2017.

- ^ Evans, Stephen (5 tháng 11 năm 2015). “Korea's hidden problem: Suicidal defectors”. BBC News. United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: British Broadcasting Corporation. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 2 tháng 6 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 17 tháng 5 năm 2016.

South Korea consistently has the highest suicide rate of all the 34 industrialized countries in the OECD.

- ^ “Why South Koreans are killing themselves in droves”. Salon. 16 tháng 3 năm 2014. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 16 tháng 3 năm 2014.

- ^ a b Kathy Novak (23 tháng 10 năm 2015). “'Forgotten': South Korea's elderly struggle to get by”. CNN. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 12 tháng 8 năm 2020. Truy cập ngày 8 tháng 8 năm 2016.

- ^ a b Se-woong Koo, "No Country For Old People" Lưu trữ 2016-08-25 tại Wayback Machine (24 September 2014), Korea Exposé.

- ^ “Age discrimination rife in Korea despite legislation”. The Korea Herald. 27 tháng 3 năm 2012. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 23 tháng 7 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 7 năm 2018.

- ^ J. Lee; J. Yang; J. Lyu (30 tháng 6 năm 2017). “Suicide Among the Elderly in Korea: A Meta-Analysis”. Innovation in Aging. 1 (suppl_1): 419. doi:10.1093/geroni/igx004.1507. PMC 6244789.

- ^ Kirk, Donald. “What 'Korean Miracle'? 'Hell Joseon' Is More Like It As Economy Flounders”. Forbes. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 12 tháng 6 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 9 tháng 6 năm 2018.

- ^ “Suicide, No.1 cause of deaths in Koreans aged 10-39”. 27 tháng 9 năm 2022.

- ^ “지난해 한국 자살률 소폭 감소...여전히 OECD 1위”. 23 tháng 9 năm 2015. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 3 tháng 10 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 9 năm 2015.

- ^ a b Kim, Kristen (12 tháng 6 năm 2015). “International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2014, Vol. 8 Issue 1, preceding p1-8. 9p. DOI: 10.1186/1752-4458-8-17. KIM KRISTEN”. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 8: 17. doi:10.1186/1752-4458-8-17. PMC 4025558. PMID 24843383.

- ^ a b c Kim, Jung Woo; Jung, Hee Young; Won, Do Yeon; Noh, Jae Hyun; Shin, Yong Seok; Kang, Tae In (2019). “Suicide Trends According to Age, Gender, and Marital Status in South Korea”. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying. 79 (1): 90–105. doi:10.1177/0030222817715756. ISSN 0030-2228. PMID 28622733. S2CID 43235972.

- ^ a b Kim, Kristen; Park, Jong-Ik (2014). “Attitudes toward suicide among college students in South Korea and the United States”. Int J Ment Health Syst. 8 (17): 17. doi:10.1186/1752-4458-8-17. PMC 4025558. PMID 24843383.

- ^ Times, New Straits (6 tháng 10 năm 2020). “Suicide, self-harm cases double among South Korea youth | New Straits Times”. NST Online (bằng tiếng Anh). Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2020. Truy cập ngày 26 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ Hur, Ji-Won, Bun-Hee Lee, Sung-Woo Lee, Se-Hoon Shim, Sang-Woo Han, and Yong-Ku Kim. "Gender Differences in Suicidal Behavior in Korea." Psychiatry Investigation, 2008, 28.

- ^ Cheong, Kyu-Seok, Min-Hyeok Choi, Byung-Mann Cho, Tae-Ho Yoon, Chang-Hun Kim, Yu-Mi Kim, and In-Kyung Hwang. "Suicide Rate Differences by Sex, Age, and Urbanicity, and Related Regional Factors in Korea." Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, 2012, 70.

- ^ Kwon, Jin-Won, Heeran Chun, and Sung-Il Cho. "A Closer Look at the Increase in Suicide Rates in South Korea from 1986–2005." BMC Public Health, 2009, 72.

- ^ Yi, Jong-Hyun; Hong, Jihyung (2020). “Socioeconomic Status and Later-life”. American Journal of Health Behavior. 44 (2): 200–213. doi:10.5993/AJHB.44.2.8. PMID 32019653.

- ^ a b c Kim, Myoung-Hee, Kyunghee Jung-Choi, Hee-Jin Jun, and Ichiro Kawachi. "Socioeconomic Inequalities in Suicidal Ideation, Parasuicides, and Completed Suicides in South Korea."Social Science & Medicine 70, no. 8 (2010): 1254-261.

- ^ a b “Lee, Gyu‐Young; Choi, Yun‐Jung; Research in Nursing & Health, Vol 38(4), Aug, 2015 pp. 301-310”. 12 tháng 6 năm 2015. Chú thích journal cần

|journal=(trợ giúp) - ^ a b c d e Park, E, Hyun, Cl Lee, EJ Lee, and SC Hong. "A Study on Regional Differentials in Death Caused by Suicide in South Korea." Europe PubMed Central, 2007.

- ^ Chen, Ying-Yeh, Nam-Soo Park, and Tsung-Hsueh Lu. "Suicide Methods Used by Women in Korea, Sweden, Taiwan and the United States." Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 108, no. 6 (2009): 452-59.

- ^ Lee, Won Jin, Eun Shil Cha, Eun Sook Park, Kyoung Ae Kong, Jun Hyeok Yi, and Mia Son. "Deaths from Pesticide Poisoning in South Korea: Trends over 10 years." International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 82, no. 3 (2008): 365-71.

- ^ Kim, Seong Yi, Myoung-Hee Kim, Ichiro Kawachi, and Youngtae Cho. "Comparative Epidemiology of Suicide in South Korea and Japan: Effects of Age, Gender and Suicide Methods." Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 2011, 5-14.

- ^ Jeon, Hong Jin, Jun-Young Lee, Young Moon Lee, Jin Pyo Hong, Seung-Hee Won, Seong-Jin Cho, Jin-Yeong Kim, Sung Man Chang, Hae Woo Lee, and Maeng Je Cho. "Unplanned versus Planned Suicide Attempters, Precipitants, Methods, and an Association with Mental Disorders in a Korea-based Community Sample." Journal of Affective Disorders 127, no. 1-3 (2010): 274-80.

- ^ Park, Subin; Ahn, Myung-Hee; Lee, Ahrong; Hong, Jin-Pyo (4 tháng 6 năm 2014). “Associations between changes in the pattern of suicide methods and rates in Korea, the US, and Finland”. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 8: 22. doi:10.1186/1752-4458-8-22. PMC 4062645. PMID 24949083.

- ^ “Jong-hyun Dead, K-Pop SHINee Singer Dies, Apparent Suicide”. 18 tháng 12 năm 2017. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 21 tháng 4 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2018.

- ^ “Bridge Signs Used in South Korea Anti-Suicide Efforts”. The World from PRX. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 4 tháng 4 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2018.

- ^ “Seoul anti-suicide initiative backfires, deaths increase by more than six times”. 26 tháng 2 năm 2014. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 4 tháng 4 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2018.

- ^ Mission Field Media (27 tháng 6 năm 2014). “Mapo Bridge a.k.a. "Suicide Bridge" - Seoul, South Korea”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 9 tháng 8 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2018 – qua YouTube.

- ^ Luke Williams (1 tháng 9 năm 2015). “Went To Mapo Bridge!”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 18 tháng 5 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2018 – qua YouTube.

- ^ VICE (2 tháng 5 năm 2016). “On Patrol with South Korea's Suicide Rescue Team”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 27 tháng 10 năm 2017. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2018 – qua YouTube.

- ^ LarrySeesAsia (10 tháng 10 năm 2014). “The Mapo "Suicide" Bridge. Seoul, SK. (Video 1 of 4)”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 18 tháng 5 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2018 – qua YouTube.

- ^ Oussayma Canbarieh (31 tháng 1 năm 2015). “Mapo - The Bridge of Death 마포대교”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 28 tháng 8 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2018 – qua YouTube.

- ^ futuexfuture (22 tháng 12 năm 2016). “생명의 다리 (Bridge of Life) - 마포대교 Mapo Bridge & Suicide Prevention (ENG)”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 18 tháng 5 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2018 – qua YouTube.

- ^ Briggs, Kevin (14 tháng 5 năm 2014). “The bridge between suicide and life”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 26 tháng 4 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2018 – qua www.ted.com.

- ^ PERPERIDIS SPYRIDONAS (18 tháng 6 năm 2013). “AD SAMSUNG BRIDGE OF LIFE SOUTH KOREA”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 15 tháng 1 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2018 – qua YouTube.

- ^ Hahn Yi, Jeongeun Hwang, Hyun-Jin Bae & Namkug Kim (2019): Age and sex subgroups vulnerable to copycat suicide: evaluation of nationwide data in South Korea Lưu trữ 2019-11-30 tại Wayback Machine, Scientific Reports.

- ^ a b c d Fu, King-Wa, C. H. Chan, and Michel Botbol. "A Study of the Impact of Thirteen Celebrity Suicides on Subsequent Suicide Rates in South Korea from 2005 to 2009." PLoS ONE, 2013, E53870.

- ^ a b Ji, Nam Ju, Weon Young Lee, Maeng Seok Noh, and Paul S.f. Yip. "The Impact of Indiscriminate Media Coverage of a Celebrity Suicide on a Society with a High Suicide Rate: Epidemiological Findings on Copycat Suicides from South Korea." Journal of Affective Disorders 156 (2014): 56-61.

- ^ a b c Kim, K., E. Ryu, M. Chon, E. Yeun, S. Choi, J. Seo, and B. Nam. "Internet Addiction In Korean Adolescents And Its Relation To Depression And Suicidal Ideation: A Questionnaire Survey." International Journal of Nursing Studies 43, no. 2 (2006): 185-92.

- ^ a b Jeon, Hong Jin, Jin Pyo Hong, Maurizio Fava, David Mischoulon, Maren Nyer, Aya Inamori, Jee Hoon Sohn, Sujeong Seong, and Maeng Je Cho. "Childhood Parental Death and Lifetime Suicide Attempt of the Opposite-Gender Offspring in a Nationwide Community Sample of Korea." Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 43, no. 6 (2013): 598-610.

- ^ a b c d e Chang, Shu-Sen, David Gunnell, Jonathan A.c. Sterne, Tsung-Hsueh Lu, and Andrew T.a. Cheng. "Was the Economic Crisis 1997–1998 Responsible for Rising Suicide Rates in East/Southeast Asia? A Time–trend Analysis for Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand." Social Science & Medicine 68, no. 7 (2009): 1322-331.

- ^ a b c B. C. Ben Park; David Lester (2008). “South Korea”. Trong Paul S. F. Yip (biên tập). Suicide in Asia: Causes and Prevention. Hong Kong University Press. tr. 27–30. ISBN 978-962-209-943-2. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 1 năm 2013.

- ^ Hu, Elise (12 tháng 11 năm 2015). “Even The Planes Stop Flying For South Korea's National Exam Day”. NPR.org. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 24 tháng 12 năm 2017. Truy cập ngày 4 tháng 4 năm 2018.

- ^ Chakrabarti, Reeta (2 tháng 12 năm 2013). “South Korea's schools: Long days, high results”. BBC News. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 29 tháng 10 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 6 năm 2018.

- ^ Kang, Yewon (20 tháng 3 năm 2014). “Poll Shows Half of Korean Teenagers Have Suicidal Thoughts”. The Wall Street Journal. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 4 tháng 5 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 4 năm 2016.

- ^ Koo, Se-Woong (1 tháng 8 năm 2014). “An Assault Upon Our Children”. The New York Times. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 28 tháng 10 năm 2015. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 11 năm 2015.

- ^ Ravitch, Diane (3 tháng 8 năm 2014). “Why We Should Not Copy Education in South Korea”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 19 tháng 9 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 11 năm 2015.Quản lý CS1: bot: trạng thái URL ban đầu không rõ (liên kết)

- ^ Carney, Matthew (16 tháng 6 năm 2015). “South Korean education success has its costs in unhappiness and suicide rates”. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 17 tháng 4 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 4 năm 2016.

- ^ a b Kwak, Chae Woon; Ickovics, Jeannette R. (1 tháng 6 năm 2019). “Adolescent suicide in South Korea: Risk factors and proposed multi-dimensional solution”. Asian Journal of Psychiatry (bằng tiếng Anh). 43: 150–153. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2019.05.027. ISSN 1876-2018. PMID 31151083. S2CID 172137934. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 30 tháng 5 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 12 năm 2020.

- ^ Lee, Claire (27 tháng 1 năm 2016). “Avoiding psychiatric treatment linked to Korea's high suicide rate”. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 4 tháng 4 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 19 tháng 11 năm 2016.

- ^ “The "Scourge of South Korea": Stress and Suicide in Korean Society” (bằng tiếng Anh). Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 17 tháng 6 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 6 năm 2018.

- ^ 조선일보 (6 tháng 4 năm 2022). “"50대 남자도 외롭다"…코로나 장기화로 자살예방센터 전화 급증”. 조선일보 (bằng tiếng Hàn). Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 4 năm 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Hendin, Herbert, Shuiyuan Xiao, Xianyun Li, Tran Thanh Huong, Hong Wang, and Ulrich Hegerl. "Suicide Prevention in Asia: Future Directions." WHO. Accessed November 4, 2014. http://www.who.int/mental_health/resources/suicide_prevention_asia_chapter10.pdf Lưu trữ 2020-12-07 tại Wayback Machine

- ^ pbs.org South Korea announces app to combat student suicide Lưu trữ 2017-09-13 tại Wayback Machine DANIEL COSTA-ROBERTS March 15, 2015