Thảo luận:Đồng tính luyến ái/Nháp 2024

Thêm đề tàiThảo luận tại Thảo luận Wikipedia:Dự án/LGBT#Dự án cải thiện bài Đồng tính luyến ái và Thảo luận:Đồng tính luyến ái#Cập nhật 2024

Làm cha mẹ[sửa mã nguồn]

Đồng tính luyến ái#? (bổ sung mới)

en:Homosexuality#Parenting

Nghiên cứu khoa học nhìn chung đã nhất quán khi chỉ ra rằng cha mẹ đồng tính nữ và đồng tính nam cũng phù hợp và có năng lực như cha mẹ dị tính, và con cái của họ có mức độ khỏe mạnh về mặt tâm lý và thích nghi tốt như những đứa trẻ được nuôi dưỡng bởi cha mẹ dị tính.[1][2][3] Theo các bài tổng quan tài liệu khoa học, không có bằng chứng ngược lại.[4][5][6][7][8]

Một bài tổng quan năm 2001 cho thấy rằng những đứa trẻ có cha mẹ đồng tính nữ hoặc đồng tính nam dường như ít thể hiện giới tính theo truyền thống hơn và có nhiều khả năng cởi mở hơn với các mối quan hệ tính dục đồng tính, một phần do di truyền (80% trẻ em được các cặp cùng giới ở Mỹ nuôi dưỡng không phải là con nuôi và hầu hết là kết quả của hôn nhân khác giới trước đó)[9] và quá trình xã hội hóa gia đình (đứa trẻ lớn lên trong bối cảnh trường học, láng giềng và xã hội tương đối khoan dung hơn, ít độc tôn dị tính hơn), mặc dù phần lớn trẻ em được nuôi dưỡng bởi các cặp cùng giới tự nhận dạng là dị tính.[10] Một bài tổng quan năm 2005 của Charlotte J. Patterson cho Hiệp hội Tâm lý Hoa Kỳ cho thấy dữ liệu hiện có không cho thấy tỷ lệ đồng tính luyến ái cao hơn ở con cái của cha mẹ đồng tính nữ hoặc đồng tính nam.[11]

Hành vi đồng tính ở động vật khác[sửa mã nguồn]

Đồng tính luyến ái#Hành vi đồng tính ở động vật khác

en:Homosexuality#Homosexual behavior in other animals

Hành vi đồng tính và song tính diễn ra ở một số loài động vật khác. Những hành vi này bao gồm hoạt động tình dục, tán tỉnh, tình cảm, ghép đôi và nuôi dạy con cái,[13] các hành vi này là phổ biến; một tổng quan năm 1999 của nhà nghiên cứu Bruce Bagemihl cho thấy hành vi đồng tính luyến ái đã được ghi nhận ở khoảng 500 loài, từ loài linh trưởng đến giun đường ruột.[13][14] Hành vi tình dục ở động vật có nhiều hình thức khác nhau, ngay cả trong cùng một loài. Động cơ và tác động của những hành vi này vẫn chưa được hiểu đầy đủ vì hầu hết các loài vẫn chưa được nghiên cứu đầy đủ.[15] Theo Bagemihl, "vương quốc động vật [thực hiện] điều đó với sự đa dạng tình dục lớn hơn nhiều—bao gồm cả tình dục cùng giới, song tính và không có tính sinh sản—so với mức độ mà cộng đồng khoa học và xã hội nói chung trước đây sẵn sàng chấp nhận."[16] Theo Bailey và các đồng nghiệp, con người và cừu nhà là những động vật duy nhất được chứng minh một cách thuyết phục là có biểu hiện xu hướng đồng tính luyến ái.[17]

Một bài báo tổng quan của N. W. Bailey và Marlene Zuk xem xét các nghiên cứu về hành vi tình dục cùng giới ở động vật đã thách thức quan điểm cho rằng các hành vi này làm giảm thành công về mặt sinh sản, trích dẫn một vài giả thuyết về tính thích nghi của hành vi tình dục cùng giới; những giả thuyết này rất khác nhau giữa các loài khác nhau. Bailey và Zuk cũng đề xuất nghiên cứu trong tương lai cần xem xét hệ quả tiến hóa của hành vi tình dục cùng giới, hơn là chỉ xem xét nguồn gốc của hành vi đó.[18]

Vào tháng 10 năm 2023, các nhà sinh vật học đã báo cáo các nghiên cứu về động vật (hơn 1.500 loài khác nhau) cho thấy hành vi cùng giới (không nhất thiết liên quan đến xu hướng đồng giới ở con người) có thể giúp cải thiện sự ổn định xã hội bằng cách giảm xung đột trong các nhóm được nghiên cứu.[19][20]

Tâm lý học[sửa mã nguồn]

Đồng tính luyến ái#Cơ sở khoa học

en:Homosexuality#Psychology

Hiệp hội Tâm lý học Hoa Kỳ, Hiệp hội Tâm thần học Hoa Kỳ và Hiệp hội Nhân viên Xã hội Quốc gia khẳng định:

| “ | Năm 1952, khi Hiệp hội Tâm thần học Hoa Kỳ công bố đầu tiên hệ thống Cẩm nang Chẩn đoán và Thống kê Rối loạn tâm thần (DSM), đồng tính luyến ái đã được liệt kê như là một rối loạn. Tuy nhiên, gần như ngay lập tức, sự phân loại đó bắt đầu được xem xét kỹ lưỡng trong nghiên cứu do Viện Sức khỏe Tâm thần Quốc gia tài trợ. Nghiên cứu đó và nghiên cứu tiếp theo liên tục thất bại trong việc đưa ra bất kỳ cơ sở thực nghiệm hoặc khoa học nào để liệt kê đồng tính luyến ái là một chứng rối loạn hoặc bất thường, thay vì một xu hướng tính dục bình thường và lành mạnh. Khi kết quả từ những nghiên cứu như vậy được tích lũy, các chuyên gia về y học, sức khỏe tâm thần, khoa học hành vi và xã hội đã đi đến kết luận rằng việc phân loại đồng tính luyến ái là một chứng rối loạn tâm thần là không chính xác và việc phân loại DSM phản ánh những giả định chưa được kiểm chứng dựa trên các chuẩn mực xã hội phổ biến một thời và ấn tượng lâm sàng từ các mẫu không mang tính đại diện bao gồm các bệnh nhân đang tìm kiếm liệu pháp điều trị và các cá nhân có hành vi đã đưa họ vào hệ thống tư pháp hình sự.

Để công nhận các bằng chứng khoa học,[21] Hiệp hội Tâm thần học Hoa Kỳ đã loại bỏ đồng tính luyến ái khỏi DSM vào năm 1973, khẳng định rằng "đồng tính luyến ái không ngụ ý sự suy giảm khả năng phán đoán, sự ổn định, độ tin cậy hoặc khả năng xã hội hoặc nghề nghiệp nói chung." Sau khi xem xét kỹ lưỡng các dữ liệu khoa học, Hiệp hội Tâm lý học Hoa Kỳ đã áp dụng quan điểm tương tự vào năm 1975 và kêu gọi tất cả các chuyên gia sức khỏe tâm thần "đi đầu trong việc xóa bỏ kỳ thị về bệnh tâm thần vốn gắn liền với xu hướng đồng tính luyến ái từ lâu". Hiệp hội Nhân viên Xã hội Quốc gia đã áp dụng chính sách tương tự. Do đó, các chuyên gia và nhà nghiên cứu sức khỏe tâm thần từ lâu đã nhận ra rằng đồng tính luyến ái không gây trở ngại cố hữu nào cho việc có một cuộc sống hạnh phúc, khỏe mạnh và hữu ích, và rằng đại đa số người đồng tính nam và đồng tính nữ hoạt động tốt trong đầy đủ các thể chế xã hội và các mối quan hệ giữa các cá nhân.[4] |

” |

Sự đồng thuận của nghiên cứu và tài liệu lâm sàng chứng minh rằng sự hấp dẫn, cảm xúc và hành vi lãng mạn và tình dục cùng giới là những biến thể bình thường và tích cực của tình dục con người.[22] Hiện nay có rất nhiều bằng chứng nghiên cứu chỉ ra rằng đồng tính nam, đồng tính nữ hoặc song tính tương thích với sức khỏe tâm thần bình thường và khả năng thích nghi xã hội.[23] ICD-9 (1977) của Tổ chức Y tế Thế giới liệt kê đồng tính luyến ái là một bệnh tâm thần; nhưng nó đã được gỡ bỏ từ ICD-10, được Hội đồng Y tế Thế giới lần thứ 43 thông qua vào ngày 17 tháng 5 năm 1990.[24][25][26] Giống như DSM-II, ICD-10 đã thêm xu hướng tính dục bất tương hợp bản ngã vào danh sách, đề cập đến những người muốn thay đổi bản dạng giới hoặc xu hướng tính dục của mình do rối loạn tâm lý hoặc hành vi (F66.1). Hiệp hội Tâm thần học Trung Quốc đã loại bỏ đồng tính luyến ái khỏi Phân loại Rối loạn Tâm thần của Trung Quốc vào năm 2001 sau 5 năm nghiên cứu.[27] Theo Đại học Tâm thần học Hoàng gia, "Lịch sử đáng tiếc này chứng tỏ việc loại trừ một nhóm người có đặc điểm tính cách cụ thể (trong trường hợp này là đồng tính luyến ái) có thể dẫn đến thực hành y tế có hại và là cơ sở cho sự phân biệt đối xử trong xã hội."[23] Để đáp lại những tuyên bố trên The Nolan Show liên quan đến đồng tính luyến ái là một chứng rối loạn tâm thần, Đại học Tâm thần Hoàng gia đã viết:[28]

Hiện nay có rất nhiều bằng chứng nghiên cứu chỉ ra rằng đồng tính nam, đồng tính nữ hoặc song tính tương thích với sức khỏe tâm thần bình thường và khả năng thích nghi xã hội. Tuy nhiên, trải nghiệm về sự phân biệt đối xử trong xã hội và khả năng bị bạn bè, gia đình và những người khác, chẳng hạn như người sử dụng lao động, từ chối, có nghĩa là một số người LGB gặp phải tỷ lệ khó khăn về sức khỏe tâm thần và vấn đề lạm dụng chất gây nghiện cao hơn dự kiến. Mặc dù đã có những tuyên bố của các nhóm chính trị bảo thủ ở Hoa Kỳ rằng tỷ lệ gặp khó khăn về sức khỏe tâm thần cao hơn là sự xác nhận rằng bản thân đồng tính luyến ái là một chứng rối loạn tâm thần, nhưng không có bằng chứng nào chứng minh cho tuyên bố đó.

Hầu hết những người đồng tính nữ, đồng tính nam và song tính tìm đến liệu pháp tâm lý đều làm như vậy vì những lý do tương tự như những người dị tính (căng thẳng, khó khăn trong mối quan hệ, khó thích nghi với các tình huống xã hội hoặc công việc, v.v.); xu hướng tính dục của họ có thể là vấn đề chính, ngẫu nhiên hoặc không quan trọng đối với các vấn đề và cách điều trị của họ. Dù vấn đề là gì đi nữa, vẫn có nguy cơ cao về thành kiến chống người đồng tính trong liệu pháp tâm lý với các khách hàng đồng tính nữ, đồng tính nam và song tính.[29] Nghiên cứu tâm lý trong lĩnh vực này có liên quan đến việc chống lại thái độ và hành động định kiến ("kỳ thị đồng tính") và phong trào quyền LGBT nói chung.[30]

Việc áp dụng thích hợp liệu pháp tâm lý khẳng định dựa trên các thực tế khoa học sau đây:[22]

- Bản thân sự hấp dẫn, hành vi và xu hướng tính dục cùng giới là những biến thể bình thường và tích cực của tính dục con người; nói cách khác, chúng không phải là dấu hiệu của rối loạn tâm thần hoặc phát triển.

- Đồng tính luyến ái và song tính bị kỳ thị và sự kỳ thị này có thể gây ra nhiều hậu quả tiêu cực (ví dụ: căng thẳng thiểu số) trong suốt cuộc đời (D'Augelli & Patterson, 1995; DiPlacido, 1998; Herek & Garnets, 2007; Meyer, 1995, 2003).

- Sự hấp dẫn và hành vi tình dục cùng giới có thể xảy ra trong bối cảnh có nhiều xu hướng tính dục và bản dạng xu hướng tính dục khác nhau. (Diamond, 2006; Hoburg et al., 2004; Rust, 1996; Savin-Williams, 2005).

- Những người đồng tính nam, đồng tính nữ và song tính có thể sống một cuộc sống thỏa mãn cũng như hình thành các mối quan hệ và gia đình ổn định, cam kết tương đương với các mối quan hệ khác giới ở những khía cạnh thiết yếu. (APA, 2005c; Kurdek, 2001, 2003, 2004; Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007).

- Không có nghiên cứu thực nghiệm hoặc nghiên cứu được bình duyệt nào ủng hộ các lý thuyết cho rằng xu hướng tính dục cùng giới là nguyên nhân dẫn đến rối loạn chức năng hoặc chấn thương gia đình (Bell et al., 1981; Bene, 1965; Freund & Blanchard, 1983; Freund & Pinkava, 1961; Hooker, 1969; McCord et al., 1962; D. K. Peters & Cantrell, 1991; Siegelman, 1974, 1981; Townes et al., 1976).

Chơi đùa trong thời thơ ấu[sửa mã nguồn]

Một số nghiên cứu cho rằng chơi đùa có thể dự đoán tình trạng đồng tính luyến ái ở trẻ mới biết đi, trong khi những nghiên cứu khác cho rằng điều này không đúng.[31] Một nghiên cứu dài hạn ủng hộ niềm tin này, được công bố vào năm 2017, đã xem xét 15 năm đầu đời của 4.500 đứa trẻ. Nó so sánh giới tính của một đứa trẻ với cách chơi khuôn mẫu, trong đó khuôn mẫu của bé trai bao gồm chơi với "xe tải đồ chơi, đấu vật 'thô bạo và nhào lộn' và chơi đùa với những bé trai khác" và khuôn mẫu của bé gái là chơi "búp bê, chơi ngôi nhà và chơi đùa với những bé gái khác." Nghiên cứu cho thấy những đứa trẻ có lối chơi phù hợp với khuôn mẫu giới tính của chúng sẽ có nhiều khả năng là người dị tính hơn và những đứa trẻ có lối chơi không phù hợp với khuôn mẫu giới tính đó sẽ ít có khả năng là người dị tính hơn.[31]

Nỗ lực chuyển đổi xu hướng tính dục[sửa mã nguồn]

Không có nghiên cứu nào đủ chặt chẽ về mặt khoa học kết luận rằng những nỗ lực thay đổi xu hướng tính dục có tác dụng thay đổi xu hướng tính dục của một người. Những nỗ lực đó đã gây tranh cãi do căng thẳng giữa một bên là các giá trị được nắm giữ bởi một số tổ chức dựa trên đức tin và các giá trị của các tổ chức bảo vệ quyền LGBT, các tổ chức chuyên môn và khoa học cũng như các tổ chức dựa trên đức tin khác.[32] Sự đồng thuận lâu dài của các ngành khoa học hành vi và xã hội cũng như các ngành y tế và sức khỏe tâm thần là đồng tính luyến ái là một biến thể bình thường và tích cực của xu hướng tính dục của con người, và do đó không phải là một rối loạn tâm thần.[32] Hiệp hội Tâm lý học Hoa Kỳ nói rằng "hầu hết mọi người có ít hoặc không có cảm giác lựa chọn về xu hướng tính dục của mình".[33] Một số cá nhân và nhóm đã thúc đẩy quan điểm đồng tính luyến ái là triệu chứng của những khiếm khuyết về phát triển hoặc những thất bại về tinh thần và đạo đức và lập luận rằng những nỗ lực thay đổi xu hướng tính dục, bao gồm cả những nỗ lực tâm lý trị liệu và tôn giáo, có thể thay đổi những cảm xúc và hành vi đồng tính luyến ái. Nhiều cá nhân và nhóm trong số này dường như nằm trong bối cảnh rộng lớn hơn của các phong trào chính trị tôn giáo bảo thủ ủng hộ việc kỳ thị đồng tính luyến ái trên cơ sở chính trị hoặc tôn giáo.[32]

Không có tổ chức chuyên môn sức khỏe tâm thần lớn nào thừa nhận những nỗ lực nhằm thay đổi xu hướng tính dục và hầu như tất cả các tổ chức này đều đã thông qua các tuyên bố chính sách cảnh báo giới chuyên môn và công chúng về các phương pháp điều trị nhằm thay đổi xu hướng tính dục. Chúng bao gồm Hiệp hội Tâm thần học Hoa Kỳ, Hiệp hội Tâm lý học Hoa Kỳ, Hiệp hội Tư vấn Hoa Kỳ, Hiệp hội Nhân viên Xã hội Quốc gia ở Hoa Kỳ,[34] Đại học Tâm thần học Hoàng gia,[35] và Hiệp hội tâm lý - xã hội học Úc.[36] Hiệp hội Tâm lý học Hoa Kỳ và Đại học Tâm thần học Hoàng gia bày tỏ lo ngại rằng quan điểm của NARTH không được khoa học ủng hộ và tạo ra một môi trường trong đó định kiến và phân biệt đối xử có thể phát triển.[35][37]

Hiệp hội Tâm thần học Hoa Kỳ cho biết "các cá nhân có thể nhận thức được ở những thời điểm khác nhau trong cuộc đời rằng họ là người dị tính, đồng tính nam, đồng tính nữ hoặc song tính" và "phản đối bất kỳ phương pháp điều trị tâm thần nào, chẳng hạn như liệu pháp 'sửa chữa' hoặc 'chuyển đổi', dựa trên giả định rằng đồng tính luyến ái thực chất là một rối loạn tâm thần, hoặc dựa trên giả định trước đó rằng bệnh nhân nên thay đổi xu hướng đồng tính luyến ái của mình". Tuy nhiên, họ khuyến khích liệu pháp tâm lý khẳng định dành cho người đồng tính nam.[38] Tương tự, Hiệp hội Tâm lý học Hoa Kỳ cũng nghi ngờ về tính hiệu quả và tác dụng phụ của các nỗ lực thay đổi xu hướng tính dục, bao gồm cả liệu pháp chuyển đổi.[39]

Hiệp hội Tâm lý học Hoa Kỳ "khuyến khích các chuyên gia sức khỏe tâm thần tránh xuyên tạc về hiệu quả của các nỗ lực thay đổi xu hướng tính dục bằng cách thúc đẩy hoặc hứa hẹn thay đổi xu hướng tính dục khi cung cấp hỗ trợ cho những cá nhân đau khổ vì xu hướng tính dục của chính họ hoặc của người khác và kết luận rằng những lợi ích được báo cáo bởi những người tham gia nỗ lực thay đổi xu hướng tính dục có thể đạt được thông qua các phương pháp tiếp cận không cố gắng thay đổi xu hướng tính dục".[32]

Nguyên nhân[sửa mã nguồn]

Đồng tính luyến ái#Cơ sở khoa học

en:Homosexuality#Causes

Mặc dù các nhà khoa học ủng hộ các mô hình sinh học vì lý do xu hướng tính dục,[40] họ không tin rằng sự phát triển xu hướng tính dục là kết quả của bất kỳ yếu tố nào. Họ thường tin rằng nó được quyết định bởi sự tương tác phức tạp giữa các yếu tố sinh học và môi trường, và được hình thành từ khi còn nhỏ.[41] Có nhiều bằng chứng ủng hộ các nguyên nhân sinh học, phi xã hội của xu hướng tính dục hơn các nguyên nhân xã hội, đặc biệt là đối với nam giới.[17][42] Không có bằng chứng xác đáng nào cho thấy việc nuôi dạy con cái hoặc trải nghiệm thời thơ ấu đóng vai trò liên quan đến xu hướng tính dục.[23] Các nhà khoa học không tin xu hướng tính dục là một sự lựa chọn.[40][43]

Viện hàn lâm Nhi khoa Hoa Kỳ đã nêu trong tạp chí Pediatrics năm 2004:

| “ | Không có bằng chứng khoa học nào cho thấy việc nuôi dạy con cái bất thường, lạm dụng tình dục hoặc các sự kiện bất lợi khác trong cuộc sống ảnh hưởng đến xu hướng tính dục. Kiến thức hiện tại cho thấy xu hướng tính dục thường được hình thành từ thời thơ ấu.[40][44] | ” |

Hiệp hội Tâm lý học Hoa Kỳ, Hiệp hội Tâm thần học Hoa Kỳ và Hiệp hội Nhân viên Xã hội Quốc gia khẳng định năm 2006:

| “ | Hiện tại, không có sự đồng thuận khoa học về các yếu tố cụ thể khiến một cá nhân trở thành dị tính, đồng tính hoặc song tính—bao gồm các tác động sinh học, tâm lý hoặc xã hội có thể có của xu hướng tính dục của cha mẹ. Tuy nhiên, bằng chứng sẵn có chỉ ra rằng đại đa số người đồng tính nữ và đồng tính nam được nuôi dưỡng bởi cha mẹ dị tính và đại đa số trẻ em được nuôi dưỡng bởi cha mẹ đồng tính nữ và đồng tính nam cuối cùng lớn lên là dị tính.[41] | ” |

"Gen đồng tính"[sửa mã nguồn]

Bất chấp nhiều nỗ lực, không có "gen đồng tính" nào được xác định. Tuy nhiên, có bằng chứng đáng kể về cơ sở di truyền của đồng tính luyến ái, đặc biệt là ở nam giới, dựa trên các nghiên cứu về cặp song sinh; một số liên kết với các vùng của Nhiễm sắc thể 8, locus Xq28 trên nhiễm sắc thể X và các vị trí khác trên nhiều nhiễm sắc thể.[45]

| Nhiễm sắc thể (NST) | Vị trí | Gen liên quan | Giới tính | Nghiên cứu1 | Nguồn gốc | Ghi chú |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NST X | Xq28 | chỉ nam giới | Hamer và cộng sự (1993) | di truyền | ||

| NST 1 | 1p36 | cả hai giới | Ellis và cộng sự (2008) | Khả năng là di truyền liên kết2 | ||

| NST 4 | 4p14 | chỉ nữ giới | Ganna và cộng sự (2019) | |||

| NST 7 | 7q31 | cả hai giới | Ganna và cộng sự (2019) | |||

| NST 8 | 8p12 | NKAIN3 | chỉ nam giới | Mustanski và cộng sự (2005) | ||

| NST 9 | 9q34 | ABO | cả hai giới | Ellis và cộng sự (2008) | Khả năng là di truyền liên kết2 | |

| NST 11 | 11q12 | OR51A7 (phỏng đoán) | chỉ nam giới | Ganna và cộng sự (2019) | Hệ khứu giác trong sở thích về bạn tình | |

| NST 12 | 12q21 | cả hai giới | Ganna và cộng sự (2019) | |||

| NST 13 | 13q31 | SLITRK6 | chỉ nam giới | Sanders và cộng sự (2017) | Gen liên quan đến trung não | |

| NST 14 | 14q31 | TSHR | chỉ nam giới | Sanders và cộng sự (2017) | ||

| NST 15 | 15q21 | TCF12 | chỉ nam giới | Ganna và cộng sự (2019) | ||

1Các nghiên cứu sơ cấp được báo cáo không phải là bằng chứng mang tính kết luận về bất kỳ mối liên hệ nào.

2Không được cho là nguyên nhân. | ||||||

Bắt đầu từ những năm 2010, các yếu tố di truyền học biểu sinh tiềm ẩn đã trở thành chủ đề được chú ý nhiều hơn trong nghiên cứu di truyền về xu hướng tính dục. Một nghiên cứu được trình bày tại Hội nghị thường niên ASHG 2015 cho thấy kiểu methyl hóa ở chín vùng của bộ gen có vẻ có mối liên hệ rất chặt chẽ với xu hướng tính dục, với thuật toán thu được sử dụng kiểu methyl hóa để dự đoán xu hướng tính dục của nhóm đối chứng với độ chính xác gần như 70%.[46][47]

Nghiên cứu về nguyên nhân của đồng tính luyến ái đóng một vai trò trong các cuộc tranh luận chính trị và xã hội, đồng thời cũng làm dấy lên mối lo ngại về hồ sơ di truyền và xét nghiệm tiền sản.[48]

Quan điểm tiến hóa[sửa mã nguồn]

Vì đồng tính luyến ái có xu hướng làm giảm khả năng thành công sinh sản và vì có bằng chứng đáng kể cho thấy xu hướng tính dục của con người bị ảnh hưởng về mặt di truyền nên vẫn chưa rõ làm thế nào nó được duy trì trong quần thể với tần suất tương đối cao.[49] Có nhiều cách giải thích, chẳng hạn như gen có xu hướng đồng tính luyến ái cũng mang lại lợi thế cho người dị tính, hiệu ứng chọn lọc theo dòng dõi, uy tín xã hội, v.v.[50] Một nghiên cứu năm 2009 cũng cho thấy sự gia tăng đáng kể về khả năng sinh sản ở những phụ nữ có liên quan đến người đồng tính thuộc nhà ngoại (nhưng không phải ở những người có quan hệ nhà nội).[51]

Tính dục và bản dạng[sửa mã nguồn]

Đồng tính luyến ái#Cơ sở khoa học

en:Homosexuality#Sexuality and identity

Hành vi và ham muốn[sửa mã nguồn]

Hiệp hội Tâm lý học Hoa Kỳ, Hiệp hội Tâm thần học Hoa Kỳ và Hiệp hội Nhân viên Xã hội Quốc gia xác định xu hướng tính dục là "không chỉ đơn thuần là một đặc điểm cá nhân có thể được xác định một cách cô lập. Đúng hơn là xu hướng tính dục của một người xác định thế giới của những người mà người ta có thể tìm thấy những mối quan hệ thỏa mãn và trọn vẹn":[4]

Xu hướng tính dục thường được thảo luận như một đặc điểm của cá nhân, như giới tính sinh học, bản dạng giới hoặc tuổi tác. Quan điểm này chưa đầy đủ vì xu hướng tính dục luôn được định nghĩa dưới dạng quan hệ và nhất thiết phải liên quan đến mối quan hệ với các cá nhân khác. Các hành vi tình dục và sự hấp dẫn lãng mạn được phân loại là đồng tính luyến ái hoặc dị tính luyến ái theo giới tính sinh học của các cá nhân liên quan đến chúng, có liên quan với nhau. Quả thực, chính bằng cách hành động—hoặc ham muốn hành động—với người khác mà các cá nhân thể hiện tính chất dị tính luyến ái, đồng tính luyến ái hoặc song tính luyến ái của mình. Điều này bao gồm những hành động đơn giản như nắm tay hoặc hôn người khác. Do đó, xu hướng tính dục gắn liền với các mối quan hệ cá nhân mật thiết mà con người hình thành với người khác nhằm đáp ứng nhu cầu cảm nhận sâu sắc về tình yêu, sự gắn bó và sự thân mật. Ngoài hành vi tình dục, những mối ràng buộc này còn bao gồm tình cảm thể xác phi tình dục giữa bạn đời, các mục tiêu và giá trị chung, sự hỗ trợ lẫn nhau và sự cam kết liên tục.[4]

Thước đo Kinsey, còn được gọi là Thước đánh giá dị tính-đồng tính luyến ái,[52] cố gắng mô tả lịch sử tình dục của một người hoặc các giai đoạn hoạt động tình dục của người đó tại một thời điểm nhất định. Nó sử dụng thang điểm từ 0, nghĩa là hoàn toàn dị tính luyến ái, đến 6, nghĩa là hoàn toàn đồng tính luyến ái. Trong cả hai tập Nam và Nữ của Báo cáo Kinsey, một cấp độ bổ sung, được liệt kê là "X", đã được các học giả giải thích là chỉ vô tính luyến ái.[53]

Bản dạng tính dục và linh hoạt tính dục[sửa mã nguồn]

Thông thường, xu hướng tính dục và bản dạng giới không được phân biệt rõ ràng, điều này có thể ảnh hưởng đến việc đánh giá chính xác bản dạng giới và liệu xu hướng tính dục có thể thay đổi hay không; Bản dạng xu hướng tính dục có thể thay đổi trong suốt cuộc đời của một cá nhân và có thể phù hợp hoặc không phù hợp với giới tính sinh học, hành vi tình dục hoặc xu hướng tính dục thực tế.[54][55][56] Xu hướng tình dục ổn định và khó có thể thay đổi đối với đại đa số mọi người, nhưng một số nghiên cứu chỉ ra rằng một số người có thể gặp phải sự thay đổi trong xu hướng tính dục của họ và điều này xảy ra ở nữ giới nhiều hơn nam giới.[57] Hiệp hội Tâm lý học Hoa Kỳ phân biệt giữa xu hướng tính dục (sự hấp dẫn bẩm sinh) và bản dạng xu hướng tính dục (có thể thay đổi tại bất kỳ thời điểm nào trong cuộc đời của một người).[58]

Quan hệ cùng giới[sửa mã nguồn]

Những người có xu hướng đồng tính luyến ái có thể thể hiện giới tính của mình theo nhiều cách khác nhau và có thể thể hiện hoặc không thể hiện điều đó qua hành vi của họ.[41] Nhiều người chủ yếu có quan hệ tình dục với người cùng giới tính, mặc dù một số có quan hệ tình dục với người khác giới, quan hệ song tính hoặc không quan hệ gì cả (sống độc thân).[41] Các nghiên cứu đã phát hiện ra rằng các cặp cùng giới và khác giới tương đương nhau về mức độ hài lòng và cam kết trong các mối quan hệ, rằng tuổi tác và giới tính đáng tin cậy hơn xu hướng tính dục như một yếu tố dự báo về sự hài lòng và cam kết đối với một mối quan hệ, và những người dị tính hoặc đồng tính luyến ái chia sẻ những kỳ vọng và lý tưởng tương tự về các mối quan hệ lãng mạn.[59][60][61]

Công khai xu hướng tính dục[sửa mã nguồn]

Công khai xu hướng tính dục là một cụm từ đề cập đến việc một người tiết lộ xu hướng tính dục hoặc bản dạng giới của họ và được mô tả và trải nghiệm một cách đa dạng như một quá trình hoặc hành trình tâm lý.[62] Nói chung, việc công khai được mô tả theo ba giai đoạn. Giai đoạn đầu tiên là "biết chính mình" và nhận ra rằng người ta cởi mở với các mối quan hệ cùng giới.[63] Điều này thường được mô tả như một sự bộc phát nội bộ. Giai đoạn thứ hai liên quan đến quyết định công khai với người khác của một người, ví dụ: gia đình, bạn bè hoặc đồng nghiệp. Giai đoạn thứ ba nói chung liên quan đến việc sống cởi mở như một người LGBT.[64] Ở Hoa Kỳ ngày nay, mọi người thường công khai ở độ tuổi trung học hoặc đại học. Ở độ tuổi này, học sinh có thể không tin tưởng hoặc yêu cầu sự giúp đỡ từ người khác, đặc biệt khi xu hướng của học sinh không được xã hội chấp nhận. Đôi khi gia đình của học sinh thậm chí không được thông báo.

Theo Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, Braun (2006), "sự phát triển của bản dạng tính dục đồng tính nữ, đồng tính nam hoặc song tính (LGB) là một quá trình phức tạp và thường khó khăn. Không giống như thành viên của các nhóm thiểu số khác (ví dụ: các dân tộc thiểu số và chủng tộc), hầu hết các cá nhân LGB không được lớn lên trong một cộng đồng gồm những người tương tự mà họ tìm hiểu về bản dạng của mình cũng như những người chi viện và hỗ trợ bản dạng đó. Đúng hơn là các cá nhân LGB thường được nuôi dưỡng trong những cộng đồng không biết gì hoặc công khai thù địch với đồng tính luyến ái."[55]

Outing là hành vi tiết lộ công khai xu hướng tính dục của một người khép kín.[65] Các chính khách, người nổi tiếng, quân nhân và giáo sĩ nổi tiếng đã outing, với các động cơ từ ác ý đến niềm tin chính trị hoặc đạo đức. Nhiều nhà bình luận hoàn toàn phản đối việc làm này,[66] trong khi một số khuyến khích các nhân vật của công chúng sử dụng vị trí ảnh hưởng của mình để làm hại những người đồng tính khác.[67]

Đồng ái[sửa mã nguồn]

Không nên nhầm lẫn đồng tính luyến ái với đồng ái, đó là sự hấp dẫn lãng mạn đối với người cùng giới tính sinh học hoặc giới tính xã hội.[68] Hầu hết những người đồng tính luyến ái cũng là những người đồng ái, nhưng một số người thuộc nhóm vô tính không trải qua hoặc trải nghiệm đồng tính luyến ái ở mức độ hạn chế. Ví dụ: những người dị tính đồng ái được mô tả là "bị thu hút một cách lãng mạn bởi người cùng giới hoặc một giới tính xã hội tương tự trong khi chỉ bị thu hút về mặt tình dục bởi người khác giới".[69]

History[sửa mã nguồn]

Đồng tính luyến ái#Lịch sử

en:Homosexuality#History

Some scholars argue that the term "homosexuality" is problematic when applied to ancient cultures since, for example, neither Greeks or Romans possessed any one word covering the same semantic range as the modern concept of "homosexuality".[70][71] Nor did there exist a distinction of lifestyle or differentiation of psychological or behavioral profiles in the ancient world.[72] However, there were diverse sexual practices that varied in acceptance depending on time and place.[70] In ancient Greece, the pattern of adolescent boys engaging in sexual practices with older males did not constitute a homosexual identity in the modern sense since such relations were seen as phases in life, not permanent orientations, since later on the younger partners would commonly marry females and reproduce.[73] Other scholars argue that there are significant continuities between ancient and modern homosexuality.[74][75]

In cultures influenced by Abrahamic religions, the law and the church established sodomy as a transgression against divine law or a crime against nature. The condemnation of anal sex between males, however, predates Christian belief. Throughout the majority of Christian history, most Christian theologians and denominations have considered homosexual behavior as immoral or sinful.[76][77] Condemnation was frequent in ancient Greece; for instance, the idea of male anal sex being "unnatural" is described by a character of Plato's,[78] though he had earlier written of the benefits of homosexual relationships.[79]

Many historical figures, including Socrates, Lord Byron, Edward II, and Hadrian,[80] have had terms such as gay or bisexual applied to them. Some scholars have regarded uses of such modern terms on people from the past as an anachronistic introduction of a contemporary construction of sexuality that would have been foreign to their times.[81][72] Other scholars see continuity instead.[82][75][74]

In social science, there has been a dispute between "essentialist" and "constructionist" views of homosexuality. The debate divides those who believe that terms such as "gay" and "straight" refer to objective, culturally invariant properties of persons from those who believe that the experiences they name are artifacts of unique cultural and social processes. "Essentialists" typically believe that sexual preferences are determined by biological forces, while "constructionists" assume that sexual desires are learned.[83] The philosopher of science Michael Ruse has stated that the social constructionist approach, which is influenced by Foucault, is based on a selective reading of the historical record that confuses the existence of homosexual people with the way in which they are labelled or treated.[84]

Africa[sửa mã nguồn]

The first record of a possible homosexual couple in history is commonly regarded as Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum, an ancient Egyptian male couple, who lived around 2400 BCE. The pair are portrayed in a nose-kissing position, the most intimate pose in Egyptian art, surrounded by what appear to be their heirs. The anthropologists Stephen Murray and Will Roscoe reported that women in Lesotho engaged in socially sanctioned "long term, erotic relationships" called motsoalle.[85] The anthropologist E. E. Evans-Pritchard also recorded that male Azande warriors in the northern Congo routinely took on young male lovers between the ages of twelve and twenty, who helped with household tasks and participated in intercrural sex with their older husbands.[86]

Americas[sửa mã nguồn]

Indigenous cultures[sửa mã nguồn]

Sac and Fox Nation ceremonial dance to celebrate the two-spirit person. George Catlin (1796–1872); Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

As is true of many other non-Western cultures, it is difficult to determine the extent to which Western notions of sexual orientation and gender identity apply to Pre-Columbian cultures. Evidence of homoerotic sexual acts and transvestism has been found in many pre-conquest civilizations in Latin America, such as the Aztecs, Mayas, Quechuas, Moches, Zapotecs, the Incas, and the Tupinambá of Brazil.[87][88][89]

The Spanish conquerors were horrified to discover sodomy openly practiced among native peoples, and attempted to crush it out by subjecting the berdaches (as the Spanish called them) under their rule to severe penalties, including public execution, burning and being torn to pieces by dogs.[90] The Spanish conquerors talked extensively of sodomy among the natives to depict them as savages and hence justify their conquest and forceful conversion to Christianity. As a result of the growing influence and power of the conquerors, many native cultures started condemning homosexual acts themselves.[cần dẫn nguồn]

Among some of the indigenous peoples of the Americas in North America prior to European colonization, a relatively common form of same-sex sexuality centered around the figure of the Two-Spirit individual (the term itself was coined only in 1990).[cần dẫn nguồn] Typically, this individual was recognized early in life, given a choice by the parents to follow the path and, if the child accepted the role, raised in the appropriate manner, learning the customs of the gender it had chosen. Two-Spirit individuals were commonly shamans and were revered as having powers beyond those of ordinary shamans. Their sexual life was with the ordinary tribe members of the same sex.[cần dẫn nguồn]

During the colonial times following the European invasion, homosexuality was prosecuted by the Inquisition, sometimes leading to death sentences on the charges of sodomy, and the practices became clandestine. Many homosexual individuals went into heterosexual marriages to maintain appearances, and many joined the (unmarried) Catholic clergy to escape public scrutiny of their lack of interest in the opposite sex.[cần dẫn nguồn]

Canada[sửa mã nguồn]

During the colonial period, both the French and the British criminalised same-sex sexual relations. Anal sex between males was a capital offence.[91] Post-Confederation, anal sex and acts of "gross indecency" continued to be criminal offences, but were no longer capital offences.[92] Individuals were prosecuted for same-sex sexual activity as late as the 1960s, which led to the federal Parliament amending the Criminal Code in 1969 to provide that anal sex between consenting adults in private (defined as only two persons) was not a criminal offence. In advocating for the law, the then-Minister of Justice, Pierre Trudeau, said: "The state has no place in the bedrooms of the nation."[93]

In 1995, the Supreme Court of Canada held that sexual orientation is a protected personal characteristic under the equality clause of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[94] The federal Parliament and provincial legislatures began to amend their laws to treat same-sex relations in the same way as opposite-sex relations. Beginning in 2003, the courts in Canada began to rule that excluding same-sex couples from marriage violated the equality clause of the Charter. In 2005, the federal Parliament enacted the Civil Marriage Act, which legalised same-sex marriage across Canada.[95]

Canada has been referred to as the most gay-friendly country in the world, ranked first in the Gay Travel Index chart in 2018, and among the five safest in Forbes magazine in 2019.[96][97] It was also ranked first in Asher & Lyric's LGBTQ+ Danger Index in a 2021 update.[98]

United States[sửa mã nguồn]

In 1986, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Bowers v. Hardwick that a state could criminalize sodomy, but, in 2003, overturned itself in Lawrence v. Texas and thereby legalized homosexual activity throughout the United States of America.

It is only since the 2010s that census forms and political conditions have facilitated the visibility and enumeration of same-sex relationships.[99]

Same-sex marriage in the United States expanded from one state in 2004 to all 50 states in 2015, through various state court rulings, state legislation, direct popular votes (referendums and initiatives), and federal court rulings.

East Asia[sửa mã nguồn]

In East Asia, same-sex love has been referred to since the earliest recorded history.

Homosexuality in China, known as the passions of the cut peach and various other euphemisms, has been recorded since approximately 600 BCE. Homosexuality was mentioned in many famous works of Chinese literature. The instances of same-sex affection and sexual interactions described in the classical novel Dream of the Red Chamber seem as familiar to observers in the present as do equivalent stories of romances between heterosexual people during the same period. Ming dynasty literature, such as Bian Er Chai (弁而釵/弁而钗), portray homosexual relationships between men as more enjoyable and more "harmonious" than heterosexual relationships.[100] Writings from the Liu Song dynasty by Wang Shunu claimed that homosexuality was as common as heterosexuality in the late 3rd century.[101]

Opposition to homosexuality in China originates in the medieval Tang dynasty (618–907), attributed to the rising influence of Christian and Islamic values,[102] but did not become fully established until the Westernization efforts of the late Qing dynasty and the Republic of China.[103]

South Asia[sửa mã nguồn]

South Asia has a recorded and verifiable history of homosexuality going back to at least 1200 BC. Hindu medical texts written in India from this period document homosexual acts and attempt to explain the cause in a neutral/scientific manner.[104][105][106] Numerous artworks and literary works from this period also describe homosexuality.[107][108][109][110]

The Pali Cannon, written in Sri Lanka between 600 BC and 100 BC, states that sexual relations, whether of homosexual or of heterosexual nature, is forbidden in the monastic code, and states that any acts of soft homosexual sex (such as masturbation and interfumeral sex) does not entail a punishment but must be confessed to the monastery. These codes apply to monks only and not to the general population.[111][112] The Kama Sutra written in India around 200 AD also described numerous homosexual sex acts positively.[113]

There were no legal restrictions on homosexuality or transsexuality for the general population prior to early modern period and colonialism, however certain dharmic moral codes forbade sexual misconduct (of both heterosexual and homosexual nature) among the upper class of persists and monks, and religious codes of foreign religions such as Christianity and Islam imposed homophobic rules on their populations.[114][115]

Hinduism describes a third gender that is equal to other genders and documentation of the third gender are found in ancient Hindu and Buddhist medical texts.[116] There are certain characters in the Mahabharata who, according to some versions of the epic, change genders, such as Shikhandi, who is sometimes said to be born as a female but identifies as male and eventually marries a woman. Bahuchara Mata is the goddess of fertility, worshipped by hijras as their patroness.

Historians have long argued that pre-colonial Indian society did not criminalise same-sex relationships, nor did it view such relations as immoral or sinful. Hinduism has traditionally portrayed homosexuality as natural and joyful.

Europe[sửa mã nguồn]

Classical period[sửa mã nguồn]

The earliest Western documents (in the form of literary works, art objects, and mythographic materials) concerning same-sex relationships are derived from ancient Greece.

In regard to male homosexuality, such documents depict an at times complex understanding in which relationships with women and relationships with adolescent boys could be a part of a normal man's love life. Same-sex relationships were a social institution variously constructed over time and from one city to another. The formal practice, an erotic yet often restrained relationship between a free adult male and a free adolescent, was valued for its pedagogic benefits and as a means of population control, though occasionally blamed for causing disorder. Plato praised its benefits in his early writings[79] but in his late works proposed its prohibition.[117] Aristotle, in the Politics, dismissed Plato's ideas about abolishing homosexuality (2.4); he explains that barbarians like the Celts accorded it a special honor (2.6.6), while the Cretans used it to regulate the population (2.7.5).[118]

Some scholars argue that there are examples of homosexual love in ancient literature, such as Achilles and Patroclus in the Iliad.[119]

Little is known of female homosexuality in antiquity. Sappho, born on the island of Lesbos, was included by later Greeks in the canonical list of nine lyric poets. The adjectives deriving from her name and place of birth (Sapphic and Lesbian) came to be applied to female homosexuality beginning in the 19th century.[120][121] Sappho's poetry centers on passion and love for various personages and both genders. The narrators of many of her poems speak of infatuations and love (sometimes requited, sometimes not) for various females, but descriptions of physical acts between women are few and subject to debate.[122][123]

In Ancient Rome, the young male body remained a focus of male sexual attention, but relationships were between older free men and slaves or freed youths who took the receptive role in sex. The Hellenophile emperor Hadrian is renowned for his relationship with Antinous, but the Christian emperor Theodosius I decreed a law on 6 August 390, condemning passive males to be burned at the stake. Notwithstanding these regulations taxes on brothels with boys available for homosexual sex continued to be collected until the end of the reign of Anastasius I in 518. Justinian, towards the end of his reign, expanded the proscription to the active partner as well (in 558), warning that such conduct can lead to the destruction of cities through the "wrath of God".[cần dẫn nguồn]

Renaissance[sửa mã nguồn]

During the Renaissance, wealthy cities in northern Italy—Florence and Venice in particular—were renowned for their widespread practice of same-sex love, engaged in by a considerable part of the male population and constructed along the classical pattern of Greece and Rome.[124][125] But even as many of the male population were engaging in same-sex relationships, the authorities, under the aegis of the Officers of the Night court, were prosecuting, fining, and imprisoning a good portion of that population.

From the second half of the 13th century, death was the punishment for male homosexuality in most of Europe.[126] The relationships of socially prominent figures, such as King James I and the Duke of Buckingham, served to highlight the issue, including in anonymously authored street pamphlets: "The world is chang'd I know not how, For men Kiss Men, not Women now;...Of J. the First and Buckingham: He, true it is, his Wives Embraces fled, To slabber his lov'd Ganimede" (Mundus Foppensis, or The Fop Display'd, 1691).

Modern period[sửa mã nguồn]

Love Letters Between a Certain Late Nobleman and the Famous Mr. Wilson was published in 1723 in England, and is presumed by some modern scholars to be a novel. The 1749 edition of John Cleland's popular novel Fanny Hill includes a homosexual scene, but this was removed in its 1750 edition. Also in 1749, the earliest extended and serious defense of homosexuality in English, Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplified, written by Thomas Cannon, was published, but was suppressed almost immediately. It includes the passage, "Unnatural Desire is a Contradiction in Terms; downright Nonsense. Desire is an amatory Impulse of the inmost human Parts."[127] Around 1785 Jeremy Bentham wrote another defense, but this was not published until 1978.[128] Executions for sodomy continued in the Netherlands until 1803, and in England until 1835, James Pratt and John Smith being the last Englishmen to be so hanged.

To this day, historians are still arguing about the question of the Sexuality of Frederick the Great (1712−1786), which essentially revolves around the taboo of whether the myth of one of the greatest war heroes in world history is allowed to be psychologically deconstructed.

Between 1864 and 1880 Karl Heinrich Ulrichs published a series of 12 tracts, which he collectively titled Research on the Riddle of Man-Manly Love. In 1867, he became the first self-proclaimed homosexual person to speak out publicly in defense of homosexuality when he pleaded at the Congress of German Jurists in Munich for a resolution urging the repeal of anti-homosexual laws.[129] Sexual Inversion by Havelock Ellis, published in 1896, challenged theories that homosexuality was abnormal, as well as stereotypes, and insisted on the ubiquity of homosexuality and its association with intellectual and artistic achievement.[130]

Although medical texts like these (written partly in Latin to obscure the sexual details) were not widely read by the general public, they did lead to the rise of Magnus Hirschfeld's Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, which campaigned from 1897 to 1933 against anti-sodomy laws in Germany, as well as a much more informal, unpublicized movement among British intellectuals and writers, led by such figures as Edward Carpenter and John Addington Symonds. Beginning in 1894 with Homogenic Love, Socialist activist and poet Edward Carpenter wrote a string of pro-homosexual articles and pamphlets, and "came out" in 1916 in his book My Days and Dreams. In 1900, Elisar von Kupffer published an anthology of homosexual literature from antiquity to his own time, Lieblingminne und Freundesliebe in der Weltliteratur.

Middle East[sửa mã nguồn]

There are a handful of accounts by Arab travelers to Europe during the mid-1800s. Two of these travelers, Rifa'ah al-Tahtawi and Muhammad as-Saffar, show their surprise that the French sometimes deliberately mistranslated love poetry about a young boy, instead referring to a young female, to maintain their social norms and morals.[131]

Israel is considered the most tolerant country in the Middle East and Asia to homosexuals,[132] with Tel Aviv being named "the gay capital of the Middle East"[133] and considered one of the most gay friendly cities in the world.[134] The annual Pride Parade in support of homosexuality takes place in Tel Aviv.[135]

On the other hand, many governments in the Middle East often ignore, deny the existence of, or criminalize homosexuality. Homosexuality is illegal in almost all Muslim countries.[136] Same-sex intercourse officially carries the death penalty in several Muslim nations: Saudi Arabia, Iran, Mauritania, northern Nigeria, and Yemen.[137] Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, during his 2007 speech at Columbia University, asserted that there were no gay people in Iran. However, the probable reason is that they keep their sexuality a secret for fear of government sanction or rejection by their families.[138]

Pre-Islamic period[sửa mã nguồn]

In ancient Sumer, a set of priests known as gala worked in the temples of the goddess Inanna, where they performed elegies and lamentations.[140]:285 Gala took female names, spoke in the eme-sal dialect, which was traditionally reserved for women, and appear to have engaged in homosexual intercourse.[141] The Sumerian sign for gala was a ligature of the signs for "penis" and "anus".[141] One Sumerian proverb reads: "When the gala wiped off his ass [he said], 'I must not arouse that which belongs to my mistress [i.e., Inanna].'"[141] In later Mesopotamian cultures, kurgarrū and assinnu were servants of the goddess Ishtar (Inanna's East Semitic equivalent), who dressed in female clothing and performed war dances in Ishtar's temples.[141] Several Akkadian proverbs seem to suggest that they may have also engaged in homosexual intercourse.[141]

In ancient Assyria, homosexuality was present and common; it was also not prohibited, condemned, nor looked upon as immoral or disordered. Some religious texts contain prayers for divine blessings on homosexual relationships. The Almanac of Incantations contained prayers favoring on an equal basis the love of a man for a woman, of a woman for a man, and of a man for man.[cần dẫn nguồn]

South Pacific[sửa mã nguồn]

In some societies of Melanesia, especially in Papua New Guinea, same-sex relationships were an integral part of the culture until the mid-1900s. The Etoro and Marind-anim for example, viewed heterosexuality as unclean and celebrated homosexuality instead. In some traditional Melanesian cultures a prepubertal boy would be paired with an older adolescent who would become his mentor and who would "inseminate" him (orally, anally, or topically, depending on the tribe) over a number of years in order for the younger to also reach puberty. Many Melanesian societies, however, have become hostile towards same-sex relationships since the introduction of Christianity by European missionaries.[142]

Law and politics[sửa mã nguồn]

Đồng tính luyến ái#Luật pháp

en:Homosexuality#Law and politics

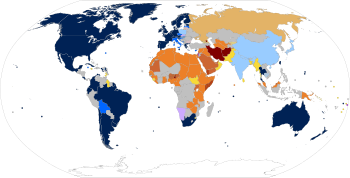

Legality[sửa mã nguồn]

| Quan hệ tình dục đồng tính bất hợp pháp. Hình phạt: | |

Tù giam; án tử không thi hành | |

Tử hình dưới tay dân quân | Tù giam, bắt giữ hoặc giam giữ |

Quản giáo, không bị cưỡng chế1 | |

| Quan hệ tình dục đồng tính hợp pháp. Chấp nhận sự chung sống dưới hình thức: | |

Hôn nhân ngoài lãnh thổ2 | |

Giới hạn đối với công dân nước ngoài | Chứng nhận có chọn lọc |

Không có | Hạn chế ở mức hành vi thể hiện XHTD đồng tính |

1Không có vụ bắt giữ nào trong ba năm qua hoặc lệnh cấm theo luật.

2Tại địa phương, việc hôn nhân không tồn tại. Một số khu vực pháp lý có thể thực hiện các loại quan hệ đối tác khác.

| Một phần của loạt bài về |

| Quyền LGBT |

|---|

|

| đồng tính nữ ∙ đồng tính nam ∙ song tính ∙ chuyển giới |

|

Chính trị |

|

Liên quan |

|

|

Most nations do not prohibit consensual sex between unrelated persons above the local age of consent. Some jurisdictions further recognize identical rights, protections, and privileges for the family structures of same-sex couples, including marriage. Some countries and jurisdictions mandate that all individuals restrict themselves to heterosexual activity and disallow homosexual activity via sodomy laws. Offenders can face the death penalty in Islamic countries and jurisdictions ruled by sharia. There are, however, often significant differences between official policy and real-world enforcement.

Although homosexual acts were decriminalized in some parts of the Western world, such as Poland in 1932, Denmark in 1933, Sweden in 1944, and England and Wales in 1967, it was not until the mid-1970s that the gay community first began to achieve limited civil rights in some developed countries. A turning point was reached in 1973 when the American Psychiatric Association, which previously listed homosexuality in the DSM-I in 1952, removed homosexuality in the DSM-II, in recognition of scientific evidence.[4] In 1977, Quebec became the first state-level jurisdiction in the world to prohibit discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. During the 1980s and 1990s, several developed countries enacted laws decriminalizing homosexual behavior and prohibiting discrimination against lesbian and gay people in employment, housing, and services. On the other hand, many countries today in the Middle East and Africa, as well as several countries in Asia, the Caribbean and the South Pacific, outlaw homosexuality. In 2013, the Supreme Court of India upheld Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code,[143] but in 2018 overturned itself and legalized homosexual activity in India.[144] Ten countries or jurisdictions, all of which are predominantly Islamic and governed according to sharia law, have imposed the death penalty for homosexuality. These include Afghanistan, Iran, Brunei, Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, and several regions in Nigeria and Jubaland.[145][146][147][148][149][150]

Laws against sexual orientation discrimination[sửa mã nguồn]

United States[sửa mã nguồn]

- Employment discrimination refers to discriminatory employment practices such as bias in hiring, promotion, job assignment, termination, and compensation, and various types of harassment. In the United States there is "very little statutory, common law, and case law establishing employment discrimination based upon sexual orientation as a legal wrong."[151] Some exceptions and alternative legal strategies are available. President Bill Clinton's Executive Order 13087 (1998) prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation in the competitive service of the federal civilian workforce,[152] and federal non-civil service employees may have recourse under the Due Process Clause of the U.S. Constitution.[153] Private sector workers may have a Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 action under a quid pro quo sexual harassment theory,[154] a "hostile work environment" theory,[155] a sexual stereotyping theory,[156] or others.[151]

- Housing discrimination refers to discrimination against potential or current tenants by landlords. In the United States, there is no federal law against such discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, but at least thirteen states and many major cities have enacted laws prohibiting it.[157]

- Hate crimes (also known as bias crimes) are crimes motivated by homophobia, or bias against an identifiable social group, usually groups defined by race (human classification), religion, sexual orientation, disability, ethnicity, nationality, age, gender, gender identity, or political affiliation. In the United States, 45 states and the District of Columbia have statutes criminalizing various types of bias-motivated violence or intimidation (the exceptions are AZ, GA, IN, SC, and WY). Each of these statutes covers bias on the basis of race, religion, and ethnicity; 32 of them cover sexual orientation, 28 cover gender, and 11 cover transgender/gender-identity.[158] In October 2009, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which "...gives the Justice Department the power to investigate and prosecute bias-motivated violence where the perpetrator has selected the victim because of the person's actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or disability", was signed into law and makes hate crime based on sexual orientation, amongst other offenses, a federal crime in the United States.[159]

European Union[sửa mã nguồn]

In the European Union, discrimination of any type based on sexual orientation or gender identity is illegal under the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.[160]

Political activism[sửa mã nguồn]

Since the 1960s, many LGBT people in the West, particularly those in major metropolitan areas, have developed a so-called gay culture. To many,[ai nói?] gay culture is exemplified by the gay pride movement, with annual parades and displays of rainbow flags. Yet not all LGBT people choose to participate in "queer culture", and many gay men and women specifically decline to do so. To some[ai nói?] it seems to be a frivolous display, perpetuating gay stereotypes.

With the outbreak of AIDS in the early 1980s, many LGBT groups and individuals organized campaigns to promote efforts in AIDS education, prevention, research, patient support, and community outreach, as well as to demand government support for these programs.

The death toll wrought by the AIDS epidemic at first seemed to slow the progress of the gay rights movement, but in time it galvanized some parts of the LGBT community into community service and political action, and challenged the heterosexual community to respond compassionately. Major American motion pictures from this period that dramatized the response of individuals and communities to the AIDS crisis include An Early Frost (1985), Longtime Companion (1990), And the Band Played On (1993), Philadelphia (1993), and Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt (1989).

Publicly gay politicians have attained numerous government posts, even in countries that had sodomy laws in their recent past. Examples include Guido Westerwelle, Germany's Vice-Chancellor; Pete Buttigieg, the United States Secretary of Transportation, Peter Mandelson, a British Labour Party cabinet minister and Per-Kristian Foss, formerly Norwegian Minister of Finance.

LGBT movements are opposed by a variety of individuals and organizations. Some social conservatives believe that all sexual relationships with people other than an opposite-sex spouse undermine the traditional family[161] and that children should be reared in homes with both a father and a mother.[162][163] Some argue that gay rights may conflict with individuals' freedom of speech,[164][165] religious freedoms in the workplace,[166][167] the ability to run churches,[168] charitable organizations[169][170] and other religious organizations[171] in accordance with one's religious views, and that the acceptance of homosexual relationships by religious organizations might be forced through threatening to remove the tax-exempt status of churches whose views do not align with those of the government.[172][173][174][175] Some critics charge that political correctness has led to the association of sex between males and HIV being downplayed.[176]

Military service[sửa mã nguồn]

Policies and attitudes toward gay and lesbian military personnel vary widely around the world. Some countries allow gay men, lesbians, and bisexual people to serve openly and have granted them the same rights and privileges as their heterosexual counterparts. Many countries neither ban nor support LGB service members. A few countries continue to ban homosexual personnel outright.[cần dẫn nguồn]

Most Western military forces have removed policies excluding sexual minority members. Of the 26 countries that participate militarily in NATO, more than 20 permit openly gay, lesbian and bisexual people to serve. Of the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, three (United Kingdom, France and United States) do so. The other two generally do not: China bans gay and lesbian people outright, Russia excludes all gay and lesbian people during peacetime but allows some gay men to serve in wartime (see below). Israel is the only country in the Middle East region that allows openly LGB people to serve in the military.[cần dẫn nguồn]

According to the American Psychological Association, empirical evidence fails to show that sexual orientation is germane to any aspect of military effectiveness including unit cohesion, morale, recruitment and retention.[177] Sexual orientation is irrelevant to task cohesion, the only type of cohesion that critically predicts the team's military readiness and success.[178]

Tham khảo[sửa mã nguồn]

- ^ “Marriage of Same-Sex Couples – 2006 Position Statement Canadian Psychological Association” (PDF). Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 19 tháng 4 năm 2009. Truy cập ngày 2 tháng 9 năm 2012.

- ^ “Elizabeth Short, Damien W. Riggs, Amaryll Perlesz, Rhonda Brown, Graeme Kane: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Parented Families – A Literature Review prepared for The Australian Psychological Society” (PDF). Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 4 tháng 3 năm 2011. Truy cập ngày 5 tháng 11 năm 2010.

- ^ “Brief of the American Psychological Association, The California Psychological Association, The American Psychiatric Association, and the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy as Amici Curiae in support of plaintiff-appellees” (PDF). Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 13 tháng 4 năm 2015. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 12 năm 2010.

- ^ a b c d e “Case No. S147999 in the Supreme Court of the State of California, In re Marriage Cases Judicial Council Coordination Proceeding No. 4365... – APA California Amicus Brief — As Filed” (PDF). tr. 30. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 3 tháng 1 năm 2020. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 12 năm 2010.

- ^ Pawelski JG, Perrin EC, Foy JM, và đồng nghiệp (tháng 7 năm 2006). “The effects of marriage, civil union, and domestic partnership laws on the health and well-being of children”. Pediatrics. 118 (1): 349–64. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1279. PMID 16818585.

- ^ Herek GM (tháng 9 năm 2006). “Legal recognition of same-sex relationships in the United States: a social science perspective” (PDF). The American Psychologist. 61 (6): 607–21. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.607. PMID 16953748. Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 10 tháng 6 năm 2010.

- ^ Biblarz, Timothy J.; Stacey, Judith (2010). “How Does the Gender of Parents Matter”. Journal of Marriage and Family. 72: 3–22. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00678.x.

- ^ “Brief presented to the Legislative House of Commons Committee on Bill C38 by the Canadian Psychological Association” (PDF). 2 tháng 6 năm 2005. Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 13 tháng 10 năm 2012. Truy cập ngày 2 tháng 9 năm 2012.

- ^ DONALDSON JAMES, SUSAN (23 tháng 6 năm 2011). “Census 2010: One-Quarter of Gay Couples Raising Children”. United States: ABC News. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 1 tháng 11 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 7 năm 2013.

Still, more than 80 percent of the children being raised by gay couples are not adopted, according to Gates.

- ^ Stacey J, Biblarz TJ (2001). “(How) Does the Sexual Orientation of Parents Matter?” (PDF). American Sociological Review. 66 (2): 159–183. doi:10.2307/2657413. JSTOR 2657413. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 28 tháng 9 năm 2011. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 7 năm 2013.

This may be partly due to genetic and family socialization processes, but what sociologists refer to as "contextual effects" not yet investigated by psychologists may also be important...even though children of lesbian and gay parents appear to express a significant increase in homoeroticism, the majority of all children nonetheless identify as heterosexual, as most theories across the essentialistt" to "social constructionist" spectrum seem (perhaps too hastily) to expect.

- ^ American Psychological Association Lesbian & Gay Parenting Lưu trữ 23 tháng 9 2015 tại Wayback Machine

- ^ Smith, Dinitia (7 tháng 2 năm 2004). “Love That Dare Not Squeak Its Name”. The New York Times. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 29 tháng 11 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 9 năm 2007.

- ^ a b (Bagemihl 1999)

- ^ Harrold, Max (16 tháng 2 năm 1999). “Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity”. The Advocate. Regent Media. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 20 tháng 5 năm 2011. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 11 năm 2023 – qua TheFreeLibrary.

- ^ Gordon, Dennis (10 tháng 4 năm 2007). “'Catalogue of Life' reaches one million species”. National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 13 tháng 7 năm 2007. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 9 năm 2007.

- ^ “Gay Lib for the Animals: A New Look At Homosexuality in Nature – 2/1/1999 – Publishers Weekly”. Publishersweekly.com. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 29 tháng 7 năm 2012. Truy cập ngày 2 tháng 9 năm 2012.

- ^ a b Bailey JM, Vasey PL, Diamond LM, Breedlove SM, Vilain E, Epprecht M (2016). “Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science”. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 17 (21): 45–101. doi:10.1177/1529100616637616. PMID 27113562.

- ^ Bailey, N. W.; Zuk, M. (2009). “Same-sex sexual behavior and evolution” (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 24 (8): 439–446. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.014. PMID 19539396. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 4 năm 2013.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (3 tháng 10 năm 2023). “Same-Sex Behavior Evolved in Many Mammals to Reduce Conflict, Study Suggests - But the researchers cautioned that the work could not shed much light on sexual orientation in humans. + comment”. The New York Times. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 4 tháng 10 năm 2023. Truy cập ngày 4 tháng 10 năm 2023.Quản lý CS1: bot: trạng thái URL ban đầu không rõ (liên kết)

- ^ Gómez, José M.; và đồng nghiệp (3 tháng 10 năm 2023). “The evolution of same-sex sexual behaviour in mammals”. Nature. 14 (5719): 5719. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.5719G. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-41290-x. PMC 10547684. PMID 37788987.

- ^ Lamberg, L. (1998). “Gay Is Okay With APA—Forum Honors Landmark 1973 Events”. JAMA. 280 (6): 497–499. doi:10.1001/jama.280.6.497. PMID 9707127. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 3 tháng 5 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 9 năm 2012.

- ^ a b American Psychological Association: Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation Lưu trữ 15 tháng 6 2010 tại Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c “Submission to the Church of England's Listening Exercise on Human Sexuality”. The Royal College of Psychiatrists. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 16 tháng 10 năm 2015. Truy cập ngày 13 tháng 6 năm 2013.

- ^ “Stop discrimination against homosexual men and women”. World Health Organisation – Europe. 17 tháng 5 năm 2011. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 9 tháng 7 năm 2012. Truy cập ngày 8 tháng 3 năm 2012.

- ^ “The decision of the World Health Organisation 15 years ago constitutes a historic date and powerful symbol for members of the LGBT community”. ILGA. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 30 tháng 10 năm 2009. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 8 năm 2010.

- ^ Shoffman, Marc (17 tháng 5 năm 2006), “Homophobic stigma – A community cause”, PinkNews.co.uk, Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 19 tháng 4 năm 2007, truy cập ngày 4 tháng 5 năm 2007

- ^ The New York Times: Homosexuality Not an Illness, Chinese Say Lưu trữ 22 tháng 7 2016 tại Wayback Machine

- ^ Royal College of Psychiatrists: “Royal College of Psychiatrists response to comments on Nolan Show regarding homosexuality as a mental disorder”. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 11 tháng 6 năm 2008. Truy cập ngày 28 tháng 6 năm 2009.

- ^ Cabaj, R; Stein, T. eds. Textbook of Homosexuality and Mental Health, p.421

- ^ Sandfort, T; và đồng nghiệp (biên tập). “Chapter 2”. Lesbian and Gay Studies: An Introductory, Interdisciplinary Approach.

- ^ a b Price, Michael (10 tháng 3 năm 2017). “Toddler play may give clues to sexual orientation”. Science.org. Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 12 năm 2023.

- ^ a b c d “Resolution on Appropriate Affirmative Responses to Sexual Orientation Distress and Change Efforts”. American Psychological Association. 2009. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 23 tháng 4 năm 2022. Truy cập ngày 18 tháng 8 năm 2022.

- ^ “Answers to Your Questions: For a Better Understanding of Sexual Orientation & Homosexuality” (PDF). American Psychological Association. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 11 tháng 1 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 20 tháng 12 năm 2010.

- ^ “Expert affidavit of Gregory M. Herek, PhD” (PDF). Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 28 tháng 8 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 8 năm 2010.

- ^ a b Royal College of Psychiatrists: Statement from the Royal College of Psychiatrists' Gay and Lesbian Mental Health Special Interest Group Lưu trữ 27 tháng 5 2010 tại Wayback Machine

- ^ Australian Psychological Society: Sexual orientation and homosexuality Lưu trữ 17 tháng 7 2009 tại Wayback Machine

- ^ “Statement of the American Psychological Association” (PDF). Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 8 năm 2010.

- ^ "LGBT-Sexual Orientation: What is Sexual Orientation?" Lưu trữ 28 tháng 6 2014 tại Wayback Machine, the official web pages of APA. Accessed 9 April 2015

- ^ “Resolution on Appropriate Affirmative Responses to Sexual Orientation Distress and Change Efforts”. apa.org. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 22 tháng 4 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 4 năm 2018.

- ^ a b c Frankowski BL; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence (tháng 6 năm 2004). “Sexual orientation and adolescents”. Pediatrics. 113 (6): 1827–32. doi:10.1542/peds.113.6.1827. PMID 15173519. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 20 tháng 3 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 18 tháng 9 năm 2012.

- ^ a b c d “Sexual orientation, homosexuality and bisexuality”. American Psychological Association. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 8 tháng 8 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 8 năm 2013.

- ^ Bogaert, Anthony F.; Skorska, Malvina N. (1 tháng 3 năm 2020). “A short review of biological research on the development of sexual orientation”. Hormones and Behavior. 119: 104659. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2019.104659. ISSN 0018-506X. PMID 31911036.

- ^ Gloria Kersey-Matusiak (2012). Delivering Culturally Competent Nursing Care. Springer Publishing Company. tr. 169. ISBN 978-0826193810. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 30 tháng 11 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 2 năm 2016.

Most health and mental health organizations do not view sexual orientation as a 'choice.'

- ^ Perrin, E. C. (2002). Sexual Orientation in Child and Adolescent Health Care. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. ISBN 0-306-46761-5.

- ^ Ngun, TC; Vilain, E (2014). “The biological basis of human sexual orientation: is there a role for epigenetics?”. Adv Genet. 86: 167–84. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800222-3.00008-5. PMID 25172350.

- ^ Balter, Michael (9 tháng 10 năm 2015). “BEHAVIORAL GENETICS. Can epigenetics explain homosexuality puzzle?”. Science. 350 (6257): 148. doi:10.1126/science.350.6257.148. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 26450189.

- ^ “Epigenetic Algorithm Accurately Predicts Male Sexual Orientation | ASHG”. ashg.org. 8 tháng 10 năm 2015. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 20 tháng 3 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 1 năm 2019.

- ^ Mitchum, Robert (12 tháng 8 năm 2007), “Study of gay brothers may find clues about sexuality”, Chicago Tribune, Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 23 tháng 10 năm 2008, truy cập ngày 4 tháng 5 năm 2007

- ^ Zietsch, B; Morley, K; Shekar, S; Verweij, K; Keller, M; Macgregor, S; Wright, M; Bailey, J; Martin, N (2008). “Genetic factors predisposing to homosexuality may increase mating success in heterosexuals”. Evolution and Human Behavior. Elsevier BV. 29 (6): 424–433. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2008.07.002. ISSN 1090-5138.

- ^ David P. Barash (19 tháng 11 năm 2012). “The Evolutionary Mystery of Homosexuality”. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 13 tháng 11 năm 2017. Truy cập ngày 13 tháng 11 năm 2017.

- ^ Iemmola, Francesca; Camperio Ciani, Andrea (2009). “New Evidence of Genetic Factors Influencing Sexual Orientation in Men: Female Fecundity Increase in the Maternal Line”. Archives of Sexual Behavior. Springer Netherlands. 38 (3): 393–9. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9381-6. PMID 18561014. S2CID 508800.

- ^ “Kinsey's Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale”. The Kinsey Institute. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 10 tháng 5 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 8 tháng 9 năm 2011.

- ^ Mary Zeiss Stange; Carol K. Oyster; Jane E. Sloan (2011). Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World. Sage Pubns. tr. 2016. ISBN 978-1-4129-7685-5. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 14 tháng 9 năm 2020. Truy cập ngày 17 tháng 12 năm 2011.

- ^ Sinclair, Karen, About Whoever: The Social Imprint on Identity and Orientation, NY, 2013 ISBN 9780981450513

- ^ a b Rosario, M.; Schrimshaw, E.; Hunter, J.; Braun, L. (2006). “Sexual identity development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Consistency and change over time”. Journal of Sex Research. 43 (1): 46–58. doi:10.1080/00224490609552298. PMC 3215279. PMID 16817067.

- ^ Ross, Michael W.; Essien, E. James; Williams, Mark L.; Fernandez-Esquer, Maria Eugenia. (2003). “Concordance Between Sexual Behavior and Sexual Identity in Street Outreach Samples of Four Racial/Ethnic Groups”. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. American Sexually Transmitted Diseases Association. 30 (2): 110–113. doi:10.1097/00007435-200302000-00003. PMID 12567166. S2CID 21881268.

- ^ *Bailey, J. Michael; Vasey, Paul; Diamond, Lisa; Breedlove, S. Marc; Vilain, Eric; Epprecht, Marc (2016). “Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science”. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 17 (2): 45–101. doi:10.1177/1529100616637616. PMID 27113562. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 11 tháng 6 năm 2020. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 9 năm 2019.

Sexual fluidity is situation-dependent flexibility in a person’s sexual responsiveness, which makes it possible for some individuals to experience desires for either men or women under certain circumstances regardless of their overall sexual orientation....We expect that in all cultures the vast majority of individuals are sexually predisposed exclusively to the other sex (i.e., heterosexual) and that only a minority of individuals are sexually predisposed (whether exclusively or non-exclusively) to the same sex.

- Dennis Coon; John O. Mitterer (2012). Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and Behavior with Concept Maps and Reviews. Cengage Learning. tr. 372. ISBN 978-1111833633. Truy cập ngày 18 tháng 2 năm 2016.

Sexual orientation is a deep part of personal identity and is usually quite stable. Starting with their earliest erotic feelings, most people remember being attracted to either the opposite sex or the same sex. ... The fact that sexual orientation is usually quite stable doesn't rule out the possibility that for some people sexual behavior may change during the course of a lifetime.

- Eric Anderson; Mark McCormack (2016). “Measuring and Surveying Bisexuality”. The Changing Dynamics of Bisexual Men's Lives. Springer Science & Business Media. tr. 47. ISBN 978-3-319-29412-4. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 24 tháng 8 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 22 tháng 6 năm 2019.

[R]esearch suggests that women's sexual orientation is slightly more likely to change than men's (Baumeister 2000; Kinnish et al. 2005). The notion that sexual orientation can change over time is known as sexual fluidity. Even if sexual fluidity exists for some women, it does not mean that the majority of women will change sexual orientations as they age – rather, sexuality is stable over time for the majority of people.

- Dennis Coon; John O. Mitterer (2012). Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and Behavior with Concept Maps and Reviews. Cengage Learning. tr. 372. ISBN 978-1111833633. Truy cập ngày 18 tháng 2 năm 2016.

- ^ “Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation” (PDF). American Psychological Association. 2009. tr. 63, 86. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 3 tháng 6 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 3 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Relationship Satisfaction and Commitment”. Eurekalert.org. 22 tháng 1 năm 2008. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 7 tháng 5 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 8 năm 2010.

- ^ Duffy, S.M/; C.E. Rusbult (1985). “Satisfaction and commitment in homosexual and heterosexual relationships”. Journal of Homosexuality. 12 (2): 1–23. doi:10.1300/J082v12n02_01. PMID 3835198. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 19 tháng 10 năm 2017. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 7 năm 2009.

- ^ Charlotte, Baccman; Per Folkesson; Torsten Norlander (1999). “Expectations of romantic relationships: A comparison between homosexual and heterosexual men with regard to Baxter's criteria”. Social Behavior and Personality. 27 (4): 363–374. doi:10.2224/sbp.1999.27.4.363. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 23 tháng 4 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 4 tháng 10 năm 2012.

- ^ “Coming Out: A Journey”. Utahpridecenter.org. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 25 tháng 8 năm 2009. Truy cập ngày 22 tháng 7 năm 2012.

- ^ In a joint statement with other major American medical organizations, the APA says that "different people realize at different points in their lives that they are heterosexual, gay, lesbian, or bisexual". “Just the Facts About Sexual Orientation & Youth: A Primer for Principals, Educators and School Personnel”. American Academy of Pediatrics, American Counseling Association, American Association of School Administrators, American Federation of Teachers, American Psychological Association, American School Health Association, The Interfaith Alliance, National Association of School Psychologists, National Association of Social Workers, National Education Association. 1999. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 7 tháng 8 năm 2007. Truy cập ngày 28 tháng 8 năm 2007.

- ^ “The Coming Out Continuum”, Human Rights Campaign, Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 2 tháng 11 năm 2007, truy cập ngày 4 tháng 5 năm 2007

- ^ Neumann, Caryn E (2004), “Outing”, glbtq.com, Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 9 tháng 6 năm 2007

- ^ Maggio, Rosalie (1991), The Dictionary of Bias-Free Usage: A Guide to Nondiscriminatory Language, Oryx Press, tr. 208, ISBN 0-89774-653-8

- ^ Tatchell, Peter (23 tháng 4 năm 2007), “Outing hypocrites is justified”, New Statesman, lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 14 tháng 9 năm 2008, truy cập ngày 4 tháng 5 năm 2007

- ^ “Asexuality, Attraction, and Romantic Orientation”. LGBTQ Center (bằng tiếng Anh). 1 tháng 7 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 2 tháng 8 năm 2023.

- ^ Team, Gayety (24 tháng 9 năm 2022). “What Does It Mean To Be Homoromantic?”. Gayety (bằng tiếng Anh). Truy cập ngày 2 tháng 8 năm 2023.

- ^ a b Hubbard, Thomas K. (2003). “Introduction”. Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: a Sourcebook of Basic Documents. University of California Press. tr. 1. ISBN 0520234308.

The term "homosexuality" is itself problematic when applied to ancient cultures, inasmuch as neither Greek nor Latin possesses any one word covering the same semantic range as the modern concept. The term is adopted in this volume not out of any conviction that a fundamental identity exists between ancient and modern practices or self-conceptions, but as a convenient shorthand linking together a range of different phenomena involving same-gender love and/or sexual activity. To be sure, classical antiquity featured a variety of discrete practices in this regard, each of which enjoyed differing levels of acceptance depending on the time and place.

- ^ Larson, Jennifer (6 tháng 9 năm 2012). “Introduction”. Greek and Roman Sexualities: A Sourcebook. Bloomsbury Academic. tr. 15. ISBN 978-1441196859.

There is no Greek or Latin equivalent for the English word 'homosexual', although the ancients did not fail to notice some individuals preferred same-sex partners.

- ^ a b Buxton, Richard (2004). “Same-Sex Eroticism”. The Complete World of Greek Mythology. London: Thames and Hudson. tr. 174. ISBN 0500251215.

As scholars have increasingly come to recognize, the ancient Greek world did not know of the modern 'life-style' category-distinction between homosexuality and heterosexuality, according to which those terms are used to designate contrasting psychological or behavioral profiles.

- ^ Buxton, Richard (2004). The Complete World of Greek Mythology. London: Thames and Hudson. tr. 148–149. ISBN 0500251215.

Readers of Plato's dialogues will be familiar with the cultural pattern according to which adolescent Greek males bonded with older men in temporary homoerotic relationships. It is misleading to describe such couples as 'homosexuals', if that term is meant to designate a person whose sexual orientation is same sex for life. In Greek society the normal assumption would have been that the younger partner would, in a later phasde in life, go on to marry and reproduce.

- ^ a b Norton, Rictor (2016). Myth of the Modern Homosexual. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781474286923. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 11 tháng 5 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 27 tháng 7 năm 2019. The author has made adapted and expanded portions of this book available online as A Critique of Social Constructionism and Postmodern Queer Theory Lưu trữ 30 tháng 3 2019 tại Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Boswell, John (1989). “Revolutions, Universals, and Sexual Categories” (PDF). Trong Duberman, Martin Bauml; Vicinus, Martha; Chauncey, George Jr. (biên tập). Hidden From History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past. Penguin Books. tr. 17–36. S2CID 34904667. Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 4 tháng 3 năm 2019.

- ^ Gnuse, Robert K. (tháng 5 năm 2015). “Seven Gay Texts: Biblical Passages Used to Condemn Homosexuality”. Biblical Theology Bulletin. SAGE Publications on behalf of Biblical Theology Bulletin Inc. 45 (2): 68–87. doi:10.1177/0146107915577097. ISSN 1945-7596. S2CID 170127256.

- ^ Koenig, Harold G.; Dykman, Jackson (2012). Religion and Spirituality in Psychiatry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. tr. 43. ISBN 9780521889520.

the overwhelming majority of Christian churches have maintained their positions that homosexual behavior is sinful

- ^ Plato; Saunders, Trevor J. (1970). The laws. Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin. tr. 340. ISBN 0-14-044222-7. OCLC 94283.

... sow illegitimate and bastard seed in courtesans, or sterile seed in males in defiance of nature.

- ^ a b Plato, Phaedrus in the Symposium

- ^ Williams, Craig A. (1999). Roman homosexuality : ideologies of masculinity in classical antiquity. Oxford. tr. 60. ISBN 0-19-511300-4. OCLC 55720140.

- ^ (Foucault 1986)

- ^ Hubbard Thomas K (22 tháng 9 năm 2003). “Review of David M. Halperin, How to Do the History of Homosexuality.”. Bryn Mawr Classical Review.

- ^ Halperin, David M. (1990). One Hundred Years of Homosexuality: And Other Essays on Greek Love. New York: Routledge. tr. 41–42. ISBN 0-415-90097-2.

- ^ Ruse, Michael (2005). Honderich, Ted (biên tập). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. tr. 399. ISBN 0-19-926479-1. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 11 tháng 5 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 9 năm 2021.

- ^ Murray, Stephen; Roscoe, Will (1998). Boy Wives and Female Husbands: Studies of African Homosexualities. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-23829-0.

- ^ Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1970). “Sexual Inversion among the Azande”. American Anthropologist. 72 (6): 1428–1434. doi:10.1525/aa.1970.72.6.02a00170. S2CID 162319598.

- ^ Pablo, Ben (2004). “Latin America: Colonial”. glbtq.com. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 11 tháng 12 năm 2007. Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 8 năm 2007.

- ^ Murray, Stephen (2004). “Mexico”. Trong Claude J. Summers (biên tập). glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. glbtq.com. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 2 tháng 11 năm 2007. Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 8 năm 2007.