Thành viên:Ctdbsclvn/nháp

Bằng chứng bên thứ ba cho các cuộc đổ bộ Mặt Trăng của Apollo là những bằng chứng hay phân tích về các cuộc hạ cánh xuống Mặt Trăng mà không xuất phát từ NASA hoặc chính phủ Mỹ (bên thứ nhất), hay những người theo thuyết âm mưu cho rằng việc đổ bộ lên Mặt Trăng của Apollo là một trò lừa đảo (bên thứ hai). Bằng chứng này cung cấp sự xác nhận độc lập lời giải thích của NASA về 6 sứ mệnh Mặt Trăng trong chương trình Apollo, kéo dài từ năm 1969 đến 1972.

Bằng chứng độc lập[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Phần này chỉ bao gồm những quan sát được thực hiện bởi các bên độc lập với NASA - không sử dụng bất kỳ cơ sở vật chất hay nhận quỹ tài trợ nào từ NASA. Mỗi quốc gia được nhắc đến trong phần này (Liên Xô, Nhật Bản, Trung Quốc và Ấn Độ) đều có các chương trình không gian của riêng họ, cũng như đã tự chế tạo tàu thăm dò được phóng từ tên lửa đẩy do chính họ xây dựng, và sở hữu mạng lưới giao tiếp không gian sâu của riêng mình.[1]

Những bức ảnh chụp của SELENE[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

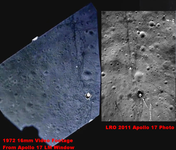

Năm 2008, tàu thăm dò Mặt Trăng SELENE của Cơ quan vũ trụ Nhật Bản (JAXA) đã chụp được một số bức ảnh cho thấy bằng chứng về những cuộc đổ bộ lên Mặt Trăng.[2] Bên trái là hai bức ảnh do các phi hành gia Apollo 15 chụp trên bề mặt Mặt Trăng vào ngày 2 tháng 8 năm 1971 trong chuyến bay EVA 3 tại trạm 9A gần Hadley Rille. Bên phải là bản tái tạo năm 2008 từ các hình ảnh được chụp bằng camera địa hình của SELENE và được chiếu 3D lên cùng một vị trí với các bức ảnh bề mặt. Địa hình xuất hiện trông gần giống nhau trong phạm vi độ phân giải 10 mét của camera SELENE.[cần dẫn nguồn]

-

AS15-82-11121: Xe đi trên Mặt Trăng Apollo 15

-

AS15-82-11122: Ảnh chụp từ Apollo 15

-

Tái tạo 3D bức ảnh của SELENE

Khu vực sáng màu của đám bụi bị thổi bay trên bề mặt Mặt Trăng được tạo ra bởi vụ nổ động cơ mô-đun Mặt Trăng tại bãi đáp Apollo 15 đã được chụp lại và xác nhận bằng phân tích so sánh với các bức ảnh hồi tháng 5 năm 2008. Chúng rất phù hợp với các bức ảnh được chụp từ Mô-đun Chỉ huy/Dịch vụ của Apollo 15 cho thấy sự thay đổi về độ phản xạ bề mặt do chùm khói. Đây là dấu vết đầu tiên có thể quan sát được của các cuộc đổ bộ của phi hành đoàn lên Mặt Trăng được nhìn thấy từ không gian kể từ khi chương trình Apollo kết thúc.[cần dẫn nguồn]

Chandrayaan-1[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Cùng với SELENE, Terrain Mapping Camera (tạm dịch là "Camera Lập bản đồ Địa hình") trên tàu thăm dò Chandrayaan-1 của Ấn Độ không có đủ độ phân giải để ghi lại phần cứng Apollo. Tuy nhiên, giống như SELENE, Chandrayaan-1 đã ghi lại bằng chứng độc lập về lớp đất nhẹ hơn, bị xáo trộn xung quanh địa điểm Apollo 15.[3][4]

Chandrayaan-2[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Tháng 4 năm 2021, tàu quỹ đạo Chandrayaan-2 của ISRO đã chụp được hình ảnh tầng hỗ trợ hạ cánh của mô-đun Mặt Trăng Đại bàng Apollo 11. Hình ảnh của tàu quỹ đạo về Tranquility Base, địa điểm hạ cánh của tàu Apollo 11, đã được ra mắt công chúng trong buổi thuyết trình vào ngày 3 tháng 9 năm 2021.[5]

Hằng Nga 2[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Tàu thăm dò Mặt Trăng thứ hai của Trung Quốc, Hằng Nga 2, được phóng vào năm 2010 có khả năng chụp ảnh bề mặt Mặt Trăng với độ phân giải lên tới 1,3 mét. Nó tuyên bố đã phát hiện ra dấu vết của cuộc đổ bộ Apollo và tàu thám hiểm Mặt Trăng, mặc dù hình ảnh liên quan chưa được xác định công khai.[6]

Các sứ mệnh Apollo được theo dõi bởi các bên độc lập[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Ngoài NASA, một số thực thể và cá nhân đã quan sát, thông qua nhiều phương tiện khác nhau, các sứ mệnh Apollo khi chúng diễn ra. Trong các sứ mệnh sau này, NASA đã công bố thông tin cho công chúng giải thích nơi các nhà quan sát của bên thứ ba có thể mong đợi được nhìn thấy các loại tàu khác nhau vào những thời điểm cụ thể theo thời gian phóng dự kiến và quỹ đạo dự kiến..[7]

Những người quan sát của tất cả các sứ mệnh[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The Soviet Union monitored the missions at their Space Transmissions Corps, which was "fully equipped with the latest intelligence-gathering and surveillance equipment".[8] Vasily Mishin, in an interview for the article "The Moon Programme That Faltered", describes how the Soviet Moon programme dwindled after the Apollo landing.[9]

The missions were tracked by radar from several countries on the way to the Moon and back.[10]

Trường Ngữ pháp Kettering[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Một nhóm tại Trường Ngữ pháp Kettering, sử dụng thiết bị vô tuyến đơn giản, đã theo dõi tàu vũ trụ của Liên Xô và Hoa Kỳ và tính toán các quỹ đạo của chúng.[11][12] Theo nhóm này, vào tháng 12 năm 1972, một thành viên đã "đón Apollo 17 trên đường tới Mặt Trăng".[13]

A group at Kettering Grammar School, using simple radio equipment, monitored Soviet and U.S. spacecraft and calculated their orbits. According to the group, in December 1972 a member "picks up Apollo 17 on its way to the Moon".

Apollo 8[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Apollo 8 was the first crewed mission to orbit the Moon, but did not land.

- On December 21, 1968, at 18:00 UT, amateur astronomers (H. R. Hatfield, M. J. Hendrie, F. Kent, Alan Heath, and M. J. Oates) in the UK photographed a fuel dump from the jettisoned S-IVB third rocket stage.[7]

- Pic du Midi Observatory (in the French Pyrenees); the Catalina Station of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory (University of Arizona); Corralitos Observatory, New Mexico, then operated by Northwestern University; McDonald Observatory of the University of Texas; and Lick Observatory of the University of California all filed reports of observations.[7]

- Dr. Michael Moutsoulas at Pic du Midi Observatory reported an initial sighting around 17:10 UT on December 21 with the 1.1-metre reflector as an object (magnitude near 10, through clouds) moving eastward near the predicted location of Apollo 8. He used a 60 cm refractor telescope to observe a cluster of objects which were obscured by the appearance of a nebulous cloud at a time which matches a firing of the service module engine to assure adequate separation from the S-IVB. This event can be traced with the Apollo 8 Flight Journal, noting that launch was at 0751 EST or 12:51 UT on December 21.[7]

- Justus Dunlap and others at Corralitos Observatory (then operated by Northwestern University) obtained over 400 short-exposure intensified images, giving very accurate locations for the spacecraft.[7]

- The 2.1 m Otto Struve Telescope at McDonald Observatory, from 01:50 to 2:37 UT on December 23, observed the brightest object flashing as bright as magnitude 15, with the flash pattern recurring about once a minute.[7]

- The Lick Observatory observations during the return coast to Earth produced live television pictures broadcast to United States west coast viewers via KQED-TV in San Francisco.[7]

- An article in the March 1969 issue of Sky & Telescope contained many reports of optical tracking of Apollo 8.[7][14]

- The first post-launch sightings were from the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) station on Maui.[7] Many in Hawaii observed the trans-lunar injection burn near 15:44 UT on December 21.[15]

Apollo 10[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Like Apollo 8, Apollo 10 orbited the Moon but did not land.

- A list of sightings of Apollo 10 were reported in "Apollo 10 Optical Tracking" by Sky & Telescope magazine, July 1969, pp. 62–63.[16]

- During the Apollo 10 mission The Corralitos Observatory was linked with the CBS news network. Images of the spacecraft going to the Moon were broadcast live.[17] :p. 17

Apollo 11[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- The Bochum Observatory director (Professor Heinz Kaminski) was able to provide confirmation of events and data independent of both the Russian and U.S. space agencies.[18]

- A compilation of sightings appeared in "Observations of Apollo 11" by Sky and Telescope magazine, November 1969.[19]

- At Jodrell Bank Observatory in the UK, the telescope was used to observe the mission, as it was used years previously for Sputnik.[20] At the same time, Jodrell Bank scientists were tracking the uncrewed Soviet spacecraft Luna 15, which was trying to land on the Moon.[21] In July 2009, Jodrell released some recordings they made.[22]

- Larry Baysinger,a radio amateur (W4EJA) and a technician for WHAS radio in Louisville, Kentucky, independently detected and recorded transmissions between the Apollo 11 astronauts on the lunar surface and the Lunar Module.[23] Recordings made by Baysinger share certain characteristics with recordings made at Bochum Observatory by Kaminski, in that both Kaminski's and Baysinger's recordings do not include the Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM) in Houston, Texas, and the associated Quindar tones heard in NASA audio and seen on NASA Apollo 11 transcripts. Kaminski and Baysinger could only hear the transmissions from the Moon, and not transmissions to the Moon from the Earth.[18][24]

- The Arcetri Observatory near Florence, Italy, also detected transmissions coming from the mission[25][26] using a 10 meters dish.[27]

Apollo 12[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Paul Maley reports several sightings of the Apollo 12 Command Module.[7]

Sky and Telescope magazine published reports of the optical sighting of this mission.[28]

Apollo 13[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Apollo 13 was intended to land on the Moon, but an oxygen tank explosion resulted in the mission being aborted after trans-lunar injection. It flew by the Moon but did not orbit or land.

Chabot Observatory calendar records an application of optical tracking during the final phases of Apollo 13, on April 17, 1970:

Rachel, Chabot Observatory's 20-inch refracting telescope, helps bring Apollo 13 and its crew home. One last burn of the lunar lander engines was needed before the crippled spacecraft's re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. In order to compute that last burn, NASA needed a precise position of the spacecraft, obtainable only by telescopic observation. All the observatories that could have done this were clouded over, except Oakland's Chabot Observatory, where members of the Eastbay Astronomical Society had been tracking the Moon flights. EAS members received an urgent call from NASA Ames Research Station, which had ties with Chabot's educational program since the 60s, and they put the Observatory's historic 20-inch refractor to work. They were able to send the needed data to Ames, and the Apollo crew was able to make the needed correction and to return safely to Earth on this date in 1970.[7]

Apollo 14[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Corralitos Observatory photographed Apollo 14.[7][29]

Sky and Telescope magazine published reports of the optical sighting of this mission.[30]

Apollo 15[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Paul Wilson and Richard T. Knadle, Jr. received voice transmissions from the Command/Service Module in lunar orbit on the morning of August 1, 1971. In an article for QST magazine they provide a detailed description of their work, with photographs.[31]

Apollo 16[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Jewett Observatory at Washington State University reported sightings of Apollo 16.[7]

At least two different radio amateurs, W4HHK and K2RIW, reported reception of Apollo 16 signals with home-built equipment.[32][33]

Bochum Observatory tracked the astronauts and intercepted the television signals from Apollo 16. The image was re-recorded in black and white in the 625 lines, 25 frames/s television standard onto 2-inch videotape using their sole quad machine. The transmissions are only of the astronauts and do not contain any voice from Houston, as the signal received came from the Moon only. The videotapes are held in storage at the observatory.[34]

Apollo 17[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Sven Grahn of the Swedish space program has described several amateur sightings of Apollo 17.[35]

Independent research consistent with NASA claims[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In this section is evidence, by independent researchers, that NASA's account is correct. However, at least somewhere in the investigation, there was some NASA involvement, or use of US government resources.

Existence and age of Moon rocks[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

A total of 382 kilôgam (842 lb) of Moon rocks and dust were collected during the Apollo 11, 12, 14, 15, 16 and 17 missions.[36] Some 10 kg (22 lb) of the Moon rocks have been used in hundreds of experiments performed by both NASA researchers and planetary scientists at research institutions unaffiliated with NASA. These experiments have confirmed the age and origin of the rocks as lunar, and were used to identify lunar meteorites collected later from Antarctica.[37] The oldest Moon rocks are up to 4.5 billion years old,[36] making them 200 million years older than the oldest Earth rocks, which are from the Hadean eon and dated 3.8 to 4.3 billion years ago. The rocks returned by Apollo are very close in composition to the samples returned by the independent Soviet Luna programme.[38][39] A rock brought back by Apollo 17 was dated to be 4.417 billion years old, with a margin of error of plus or minus 6 million years. The test was done by a group of researchers headed by Alexander Nemchin at Curtin University of Technology in Bentley, Australia.[40]

Retroreflectors[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The detection on Earth of reflections from laser ranging retro-reflectors (LRRRs, or arrays of corner-cube prisms used as targets for Earth-based tracking lasers) on Lunar Laser Ranging experiments left on the Moon is evidence of landings.[41][42][43][44]

Quoting from James Hansen's 2005 biography of Neil Armstrong, First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong:

For those few misguided souls who still cling to the belief that the Moon landings never happened, examination of the results of five decades of LRRR experiments should evidence how delusional their rejection of the Moon landing really is.[45]

The NASA-independent Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur, McDonald, Apache Point, and Haleakalā observatories regularly use the Apollo LRRR.[46] Lick Observatory attempted to detect from Apollo 11's retroreflector while Armstrong and Aldrin were still on the Moon but did not succeed until August 1, 1969.[47] The Apollo 14 astronauts deployed a retroreflector on February 5, 1971, and McDonald Observatory detected it the same day. The Apollo 15 retroreflector was deployed on July 31, 1971, and was detected by McDonald Observatory within a few days.[48]

The image on the left shows what is considered some of the most unambiguous evidence. This experiment repeatedly fires a laser at the Moon, at the spots where the Apollo landings were reported. The dots show when photons are received from the Moon. The dark line shows that a large number come back at a specific time, and hence were reflected by something quite small (well under a metre in size). Photons reflected from the surface come back over a much broader range of times (the whole vertical range of the plot corresponds to only 18 metres or so in range). The concentration of photons at a specific time appears when the laser is aimed at the Apollos 11, 14 or 15 landing sites; otherwise the expected featureless distribution is observed.[49] The Apollo reflectors are still in use.[50]

Strictly speaking, although retroreflectors left by Apollo astronauts are strong evidence that human-manufactured artifacts currently exist on the Moon and that human visitors left them there, they are not, on their own, conclusive evidence. Uncrewed missions are known to have placed such objects on the Moon, albeit not before 1970. Smaller retroreflectors were carried by the uncrewed landers Lunokhod 1 and Lunokhod 2 in 1970 and 1973, respectively.[50] The location of Lunokhod 1 was unknown for nearly 40 years but it was rediscovered in 2010 in photographs by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and its retroreflector is now in use. Both the United States and the USSR had the capability to soft-land objects on the surface of the Moon for several years before that. The USSR successfully landed its first uncrewed probe (Luna 9) on the Moon in February 1966, and the United States followed with Surveyor 1 in June 1966, but no uncrewed landers carried retroreflectors before Lunokhod 1 in November 1970. The retroreflectors are proof that human-made probes reached the exact locations of the Apollo 11, 14, and 15 landing sites at exactly the same time as those missions.

Radio-telescopic observations[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In October-November 1977, the Soviet radio telescope RATAN-600 observed all five transmitters of ALSEP scientific packages placed on the Moon surface by all Apollo landing missions excluding Apollo 11. Their selenographic coordinates and the transmitter power outputs (20 W) were in agreement with the NASA reports.[51]

Photographs[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Ground-based telescopes[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In 2002, astronomers tested the optics of the Very Large Telescope by imaging the Apollo landing sites.[52] The telescope was used to image the Moon and provided a resolution of 130 mét (430 ft), which was not good enough to resolve the 4,2 mét (14 ft)[chuyển đổi: số không hợp lệ] wide lunar landers or their long shadows.[53]

New lunar missions[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Post-Apollo lunar exploration missions have located and imaged artifacts of the Apollo program remaining on the Moon's surface.

Images taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission beginning in July 2009 show the six Apollo Lunar Module descent stages, Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) science experiments, astronaut footpaths, and lunar rover tire tracks. These images are the most effective proof to date to rebut the "landing hoax" theories.[54][55][56] Although this probe was indeed launched by NASA, the camera and the interpretation of the images are under the control of an academic group — the LROC Science Operations Center at Arizona State University, along with many other academic groups.[57] At least some of these groups, such as German Aerospace Center, Berlin, are not located in the US, and are not funded by the US government.[58]

After the images shown here were taken, the LRO mission moved into a lower orbit for higher resolution camera work. All of the sites have since been re-imaged at higher resolution.[59][60] Comparison of the original 16 mm Apollo 17 LM camera footage during ascent to the 2011 LRO photos of the landing site show an almost exact match of the rover tracks.[61]

Further imaging in 2012 shows the shadows cast by the flags planted by the astronauts on all Apollo landing sites. The exception is that of Apollo 11, which matches Buzz Aldrin's account of the flag being blown over by the lander's rocket exhaust on leaving the Moon.[62]

-

Higher resolution image of the Apollo 17 landing site showing the Challenger lunar module descent stage as photographed by the LRO

-

Apollo 14 landing site, photograph by LRO

-

Apollo 12 landing site

-

Apollo 15 landing site (by LRO)

-

Apollo 15 landing site (from Lunar Module film)

-

Comparison of the Apollo 17 landing site between the original 16 mm footage shot from the LM window during ascent in 1972, and the 2011 lunar reconnaissance orbiter image of the Apollo 17 landing site. From the EEVdiscover video.

Ultraviolet photographs[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Long-exposure photos were taken with the Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph by Apollo 16 on April 21, 1972, from the surface of the Moon. Some of these photos show the Earth with stars from the Capricornus and Aquarius constellations in the background. The European Space Research Organisation's TD-1A satellite later scanned the sky for stars that are bright in ultraviolet light. The TD-1A data obtained with the shortest passband is a close match for the Apollo 16 photographs.[63]

Apollo missions tracked by non-NASA personnel[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

This section contains reports of the lunar missions from facilities that had significant numbers of non-NASA employees. This includes facilities such as the Deep Space Network, which employed (and still employs) many local citizens in Spain and Australia, and facilities such as the Parkes Observatory, which were hired by NASA for specific tasks, but staffed by non-NASA personnel.

Observers of all missions[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The NASA Manned Space Flight Network (MSFN) was a worldwide network of stations that tracked the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Skylab missions. Most MSFN stations were only needed during the launch, Earth orbit and landing phases of the lunar missions, but three "deep space" sites with larger antennas provided continuous coverage during the trans-lunar, trans-Earth and lunar mission phases. Today, these three sites form the NASA Deep Space Network: the Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex near Goldstone, California; the Madrid Deep Space Communication Complex near Madrid, Spain; and the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, adjacent to the Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve, near Canberra, Australia.

Although most MSFN stations were NASA-owned, they employed many local citizens. NASA also contracted the Parkes Observatory in New South Wales, Australia, to supplement the three deep space sites, most famously during the Apollo 11 EVA as documented by radio astronomer John Sarkissian[64] and portrayed (humorously and not quite accurately) in the 2000 film The Dish. The Parkes Observatory is not NASA-owned; it is, and always has been, owned and operated by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), a research agency of the Australian government. It would have been relatively easy for NASA to avoid using the Parkes Observatory to receive the Apollo 11 EVA television signals by scheduling the EVA at an earlier time when the Goldstone station could provide complete coverage.

Apollo 11[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- The Madrid Apollo Station, now part of the Deep Space Network, built in Fresnedillas, near Madrid, Spain, tracked Apollo 11.[65] A large majority of the people working at this station were not employees of NASA, but of Spain's Instituto Nacional de Técnica Aeroespacial.[66]

Apollo 12[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Parts of Surveyor 3, which landed on the Moon in April 1967, were brought back to Earth by Apollo 12 in November 1969.[67] These samples were shown to have been exposed to lunar conditions.[68]

Xem thêm[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Trích dẫn[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- ^ See, for example, the references in the articles Indian Deep Space Network, Chinese Deep Space Network, Soviet Deep Space Network, ESTRACK (European Deep Space Network), and Japanese Deep Space Network.

- ^ “The "halo" area around Apollo 15 landing site observed by Terrain Camera on SELENE (KAGUYA)” (Thông cáo báo chí). Chōfu, Tokyo: Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. 20 tháng 5 năm 2008. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 14 tháng 3 năm 2022. Truy cập ngày 20 tháng 5 năm 2008.

- ^ drbuzz0 (7 tháng 11 năm 2009). “Apollo 15: Confirmed Times Three”. Depleted Cranium (Blog). Steve Packard. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 17 tháng 9 năm 2012. Truy cập ngày 2 tháng 5 năm 2013.

- ^ Chauhan, Prakash; Kirankumar, A. S. (10 tháng 9 năm 2009). “Chandrayaan-1 captures Halo around Apollo-15 landing site using stereoscopic views from Terrain Mapping Camera” (PDF). Current Science. Current Science Association in collaboration with the Indian Academy of Sciences. 97 (5): 630–31. ISSN 0011-3891.

- ^ GUJCOST Celebrates Vigyan Utsav (STI Ecosystem for Atmanirbhar Bharat) | 3rd September 2021 (bằng tiếng Anh), truy cập ngày 25 tháng 10 năm 2021

- ^ ZHANG, Nannan biên tập (7 tháng 2 năm 2012). “China Publishes High-resolution Full Moon Map”. english.cas.cn. Beijing: Chinese Academy of Sciences. Truy cập ngày 9 tháng 1 năm 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Keel, Bill (tháng 8 năm 2008). “Telescopic Tracking of the Apollo Lunar Missions”. Bill Keel's Space History Bits.

- ^ Scott & Leonov 2004, p. 247

- ^ “The Moon Programme That Faltered”. Spaceflight. London: British Interplanetary Society. 33: 2–3. tháng 3 năm 1991. Bibcode:1991SpFl...33....2.

- ^ Hansen 2005, p. 639

- ^ Perry, G. E. (1968). “A school satellite tracking station as an aid to the teaching of physics” (PDF). Physics Education. 3 (6): 281. Bibcode:1968PhyEd...3..281P. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/3/6/301.

- ^ Roberts, G. (1986). “The Amateur and Artificial Satellites”. Monthly Notes of the Astronomical Society of South Africa. 45: 5. Bibcode:1986MNSSA..45....5R.

- ^ Christy, Robert D. “Kettering Group Timeline”. zarya.info. Truy cập ngày 9 tháng 5 năm 2013.

- ^ Liemohn, Harold B. (1969). “Feature Optical Observations of Apollo 8”. Sky and Telescope (3): 156.

- ^ Swaim, Dave (22 tháng 12 năm 1968). “Apollo 8 Mission Leaves Earth on Historic Voyage”. Independent Star News. Pasadena, California. tr. 1. Truy cập ngày 9 tháng 5 năm 2013.

The TLI firing was begun at 7:41 a.m. (PST) while the craft was over Hawaii, and it was reported there that the burn was visible from the ground.

- ^ “Apollo 10 Optical Tracking”. Sky and Telescope (7): 62–63. 1969.

- ^ Hynek, J. Allen (tháng 4 năm 1976). “The Corralitos Observatory Program for the Detection of Lunar Transient Phenomena”. NASA Technical Reports Server. NASA. 76: 23125. Bibcode:1976STIN...7623125H. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 9 tháng 5 năm 2013.

- ^ a b “Bochum”. A Tribute to Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station.

- ^ “Observations of Apollo 11”. Sky and Telescope (11): 358–359. 1969.

- ^ Portillo, Michael (2 tháng 6 năm 2005). “The other space race: Transcript”. OpenLearn. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 2 năm 2006.

- ^ “Recording of Russia's lunar gatecrash attempt released”. Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics. 3 tháng 7 năm 2009. Truy cập ngày 20 tháng 7 năm 2009.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan (3 tháng 7 năm 2009). “Recording tracks Russia's Moon gatecrash attempt”. The Independent. London. Truy cập ngày 20 tháng 7 năm 2009.

- ^ Rutherford, Glenn (23 tháng 7 năm 1969). “Lunar Eavesdropping: Louisvillians Hear Moon Walk Talk on Homemade Equipment”. The Courier-Journal. Louisville, KY. tr. B1. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2013.

- ^ “Otter Creek-South Harrison Observatory”. Lunar Eavesdropping in Louisville, Kentucky.

- ^ Bucciantini, Niccolò (16 tháng 7 năm 2019). “Così da Arcetri captarono lo sbarco sulla Luna”. MEDIA INAF (bằng tiếng Ý). Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 11 năm 2021.

- ^ “La notte che da Arcetri ascoltarono gli astronauti parlare sulla luna”. la Repubblica (bằng tiếng Ý). 16 tháng 7 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 11 năm 2021.

- ^ Cantù, A. M.; Felli, M.; Landini, M.; Tofani, G. (1967). “1967MmSAI..38..539C Page 539”. Memorie della Societa Astronomica Italiana. 38: 539. Bibcode:1967MmSAI..38..539C. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 11 năm 2021.

- ^ “Optical Observations of Apollo 12”. Sky and Telescope (2): 127. 1970.

- ^ Kantrowitz, Arthur (1 tháng 4 năm 1971). “The Relevance of Space (inset Apollo 14)”. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc.: 33. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 1 năm 2023.

- ^ “Some Optical Observations of Apollo 14”. Sky and Telescope (4): 251. 1971.

- ^ Wilson, P. M.; Knadle, R. T. (tháng 6 năm 1972). “Houston, This is Apollo...”. QST. Newington, Connecticut: American Radio Relay League: 60–65.

- ^ “432 Record, W4HHK Apollo 16 Reception”. QST. Newington, Connecticut: American Radio Relay League. tháng 6 năm 1971. tr. 93–94.

- ^ “K2RIW Apollo 16 Reception & 2300 EME”. QST. Newington, Connecticut: American Radio Relay League. tháng 7 năm 1971. tr. 90–91.

- ^ Kaminski, H. (October–November 1972). “Sternwarte Bochum beobachtet US-Apollo-Mondexperimente” [Bochum Observatory Observed U.S. Apollo Moon Experiments] (PDF). Neues von Rohde & Schwarz (bằng tiếng Đức). 57. Munich: Rohde & Schwarz. tr. 24–27. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 4 năm 2011.

- ^ Grahn, Sven. “Tracking Apollo-17 from Florida”. Sven's Space Place.

- ^ a b James Papike; Grahm Ryder & Charles Shearer (1998). “Lunar Samples”. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 36: 5.1–5.234.

- ^ Pearlman, Robert (27 tháng 9 năm 2000). “House Passes Bill to Award Apollo Astronauts Moon Rocks”. Space.com. New York: TechMediaNetwork, Inc. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 17 tháng 10 năm 2000. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2013.

- ^ Laul, JC; Schmitt, RA (1973). “Chemical composition of Luna 20 rocks and soil and Apollo 16 soils”. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 37 (4): 927–942. Bibcode:1973GeCoA..37..927L. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(73)90190-7.

- ^ Baryshev, VB; Kudryashova, AF; Tarasov, LS; Ulyanov, AA; Zolotarev, KV (2001). “Geochemistry of rare elements in different types of lunar rocks (based on μXFA-SR data)”. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A. 470 (1–2): 422–425. Bibcode:2001NIMPA.470..422B. doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(01)01089-0.

- ^ Pendick, Daniel (tháng 6 năm 2009). “Apollo sample pinpoints lunar crust's age”. Astronomy. Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Publishing. 37 (6): 16.

- ^ Phillips, Tony (20 tháng 7 năm 2004). “What Neil & Buzz Left on the Moon”. Science@NASA. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 5 tháng 4 năm 2010.

- ^ “Laser Ranging Retroreflector”. NSSDC Master Catalog. National Space Science Data Center. NSSDC ID: 1971-063C-08. Truy cập ngày 8 tháng 7 năm 2009.

- ^ Anderson, John D. (tháng 3 năm 2009). “Is there something we don't know about gravity?”. Astronomy. Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Publishing. 37 (3): 22–27.

- ^ Dorminey, Bruce (tháng 3 năm 2011). “Secrets beneath the Moon's surface”. Astronomy. Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Publishing. 39 (3): 24–29.

- ^ Hansen 2005, pp. 515–516

- ^ Bouquillon, S.; Chapront, J.; Francou, G. “Contribution of SLR Results to LLR Analysis” (PDF). Paris: Observatoire de Paris. Truy cập ngày 26 tháng 7 năm 2007. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the "Journées 2005 Systèmes de référence spatio-temporels," held at the Space Research Centre of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland, September 19–21, 2005.

- ^ Hansen 2005, p. 515

- ^ Bender, P. L.; Currie, D. G.; Dicke, R. H.; và đồng nghiệp (19 tháng 10 năm 1973). “The Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment” (PDF). Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 182 (4109): 229–238. Bibcode:1973Sci...182..229B. doi:10.1126/science.182.4109.229. PMID 17749298. S2CID 32027563. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 5 năm 2013.

- ^ Murphy, Tom. “APOLLO (the Apache Point Observatory Lunar Laser-ranging Operation)”.

- ^ a b Williams, James G.; Dickey, Jean O. (tháng 10 năm 2002). Lunar Geophysics, Geodesy, and Dynamics (PDF). 13th International Workshop on Laser Ranging.

- ^ Naugolnaia, M. N.; Spangenberg, E. E.; Soboleva, N. S.; Fomin, V. A. Determination of selenographic coordinates of objects by RATAN-600. Pisma v Astronomicheskii Zhurnal, vol. 4, Dec. 1978, p. 562-565. (Soviet Astronomy Letters, vol. 4, Nov.-Dec. 1978, p. 302-303).

- ^ Matthews, Robert (24 tháng 11 năm 2002). “World's biggest telescope to prove Americans really walked on Moon”. The Sunday Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 5 năm 2013.

- ^ Lawrence, Pete (17 tháng 7 năm 2019). “How to find Apollo 11's landing site on the Moon”. Sky at Night Magazine. BBC. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 3 năm 2020.

- ^ Hautaluoma, Grey; Freeberg, Andy (17 tháng 7 năm 2009). Garner, Robert (biên tập). “LRO Sees Apollo Landing Sites”. NASA. Truy cập ngày 18 tháng 7 năm 2007.

NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, or LRO, has returned its first imagery of the Apollo Moon landing sites. The pictures show the Apollo missions' lunar module descent stages sitting on the moon's surface, as long shadows from a low sun angle make the modules' locations evident.

- ^ Talcott, Richard (tháng 11 năm 2009). “LRO takes first Moon images”. Astronomy. 37 (11): 22. ISSN 0091-6358.

- ^ Robinson, Mark (17 tháng 7 năm 2009). “LROC's First Look at the Apollo Landing Sites”. LROC News System. Truy cập ngày 17 tháng 7 năm 2009.

- ^ “Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera - Our Team”.

- ^ “Institute of Space Systems”.

- ^ Robinson, Mark (29 tháng 9 năm 2009). “Apollo 11: Second look”. LROC News System. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 5 năm 2013.

- ^ Robinson, Mark (28 tháng 10 năm 2009). “Exploring the Apollo 17 Site”. LROC news system. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 5 năm 2013.

- ^ Jones, David (26 tháng 7 năm 2017). “How To Prove We Landed On The Moon”. EEVblog. Truy cập ngày 26 tháng 7 năm 2017.

- ^ “Apollo Moon flags still standing, images show”. BBC News. London: BBC. 30 tháng 7 năm 2012. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 7 năm 2012.

- ^ Keel, William C. (tháng 7 năm 2007). “The Earth and Stars in the Lunar Sky”. Skeptical Inquirer. 31 (4): 47–50.

- ^ Sarkissian, John M. (2001). “On Eagle's Wings: The Parkes Observatory's Support of the Apollo 11 Mission”. Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing for the Astronomical Society of Australia. 18 (3): 287–310. Bibcode:2001PASA...18..287S. doi:10.1071/AS01038. Truy cập ngày 2 tháng 5 năm 2013. October 2000 website version, part 1 of 12: "Introduction." Original version available from CSIRO Parkes Observatory (PDF).

- ^ “The Fresnedillas (Madrid, Spain) MSFN station”. A Tribute to Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station.

- ^ “Madrid Apollo Facility NASA/INTA Personnel Roster” (PDF). 29 tháng 2 năm 1972.

- ^ Oberg, James (tháng 11 năm 2007). “50th anniversary of first microbes in orbit”. Astronomy. Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Publishing. 35 (11): 2.

- ^ Price, P. Buford; Zinner, Ernst (2004). “Robert M. Walker” (PDF). Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 6 tháng 7 năm 2007.

Tham khảo[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- Hansen, James R. (2005). First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-743-25631-5.

- Scott, David; Leonov, Alexei; Toomey, Christine (2004). Two Sides of the Moon: Our Story of the Cold War Space Race. Foreword by Neil Armstrong; introduction by Tom Hanks (ấn bản 1). New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 0-312-30865-5.

Liên kết ngoài[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- "Relative Signal Strengths Using Lunar Retroreflectors" shows calculations of relative signal gain when using retroreflectors for Lunar ranging.

- "Telescopic Tracking of the Apollo Lunar Missions" at Bill Keel's Space History Bits