Flavonoid

Flavonoid (hoặc bioflavonoid) (bắt nguồn từ Latin flavus nghĩa là màu vàng, màu của flavonoid trong tự nhiên) là một loại chất chuyển hóa trung gian của thực vật. Tuy nhiên một số flavonoid có màu xanh, tím đỏ và cũng có một số khác lại không có màu. Trong thực vật cũng có một số nhóm hợp chất khác không thuộc flavonoid nhưng lại có màu vàng như carotenoid, anthranoid, xanthon có thể gây nhầm lẫn.

Flavonoid được gọi là vitamin P (do tác dụng thẩm thấu vào thành mạch máu) từ giữa những năm 1930 đến những năm 50 đầu, nhưng thuật ngữ này đã lỗi thời và không còn được sử dụng.[1]

Theo danh pháp IUPAC,[2][3], flavonoid có thể được chia thành:

- flavonoid hoặc bioflavonoid.

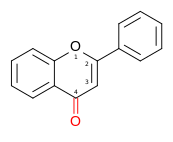

- isoflavonoid, bắt nguồn từ cấu trúc của 3-phenylchromen-4-one (3-phenyl-1,4-benzopyrone)

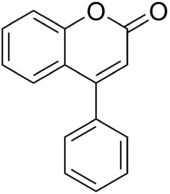

- neoflavonoid, bắt nguồn từ cấu trúc của 4-phenylcoumarine (4-phenyl-1,2-benzopyrone).

Thuật ngữ flavonoid và bioflavonoid do mô tả các hợp chất polyhydroxy polyphenol không chứa ketone không sát nghĩa nên được gọi một cách chuyên biệt hơn là flavanoids.

Chức năng của flavonoid trong thực vật[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Flavonoid phổ biến ở nhiều loại thực vật và có nhiều chức năng.

Flavonoid là một sắc tố sinh học, sắc tố thực vật quan trọng tạo ra màu sắc của hoa, cụ thể giúp sản xuất sắc tố vàng, đỏ, xanh cho cánh hoa để thu hút nhiều động vật đến thụ phấn.

Trong thực vật bậc cao, flavonoids tham gia vào lọc tia cực tím (UV), cộng sinh cố định đạm và sắc tố hoa.

Flavonoids có thể hoạt động như một chất chuyển giao hóa học hoặc điều chỉnh sinh lý. Flavonoids cũng có thể hoạt động như các chất ức chế chu kỳ tế bào.

Flavonoids được tiết ra bởi rễ các cây chủ để giúp vi khuẩn Rhizobia trong giai đoạn lây nhiễm của mối quan hệ cộng sinh với các cây họ đậu (legumes) như đậu cô ve, đậu hà lan, cỏ ba lá (clover), và đậu nành. Rhizobia sống trong đất có thể cảm nhận được chất flavonoid và tiết ra các chất tiếp nhận. Các chất này lần lượt được các cây chủ nhận biết và có thể dẫn đến sự biến dạng các rễ cũng như một số phản ứng của tế bào chẳng hạn như chất khử tạp chất ion và sự hình thành nốt sần ở rễ (root nodule).

Ngoài ra, một số chất flavonoid có hoạt tính ức chế chống lại các sinh vật gây ra như bệnh ở thực vật như Fusarium oxysporum.[4]

Phân nhóm[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Hơn 5000 flavonoid tự nhiên được đặc trưng bởi nhiều loại thực vật khác nhau và được phân loại theo cấu trúc hóa học, và thường được chia thành các phân nhóm sau đây (tham khảo thêm [5]):

Anthoxanthin[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Anthoxanthin được chia ra thành hai nhóm:[6]

| Nhóm | Khung (skeleton) | Các ví dụ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mô tả | Nhóm chức năng | Công thức cấu tạo | |||

| 3-hydroxyl | 2,3-dihydro | ||||

| Flavone | 2-phenylchromen-4-one | ✗ | ✗ |

|

Luteolin, Apigenin, Tangeritin |

| Flavonol or 3-hydroxyflavone |

3-hydroxy-2-phenylchromen-4-one | ✓ | ✗ |

|

Quercetin, Kaempferol, Myricetin, Fisetin, Isorhamnetin, Pachypodol, Rhamnazin,Pyranoflavonol, Furanoflavonol |

Flavanone[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

| Nhóm | Khung (skeleton) | Các ví dụ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mô tả | Nhóm chức năng | Công thức cấu tạo | |||

| 3-hydroxyl | 2,3-dihydro | ||||

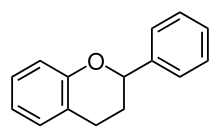

| Flavanone | 2,3-dihydro-2-phenylchromen-4-one | ✗ | ✓ |

|

Hesperetin, Naringenin, Eriodictyol, Homoeriodictyol |

Flavanonol[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

| Nhóm | Khung (skeleton) | Các ví dụ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mô tả | Nhóm chức năng | Công thức cấu tạo | |||

| 3-hydroxyl | 2,3-dihydro | ||||

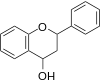

| Flavanonol or 3-Hydroxyflavanone or 2,3-dihydroflavonol |

3-hydroxy-2,3-dihydro-2-phenylchromen-4-one | ✓ | ✓ |

|

Taxifolin (hoặc Dihydroquercetin), Dihydrokaempferol |

Flavan[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Gồm flavan-3-ol (flavanols), flavan-4-ol và flavan-3,4-diol.

| Khung | Tên |

|---|---|

|

Flavan-3-ol (flavanol) |

|

Flavan-4-ol |

|

Flavan-3,4-diol (leucoanthocyanidin) |

- Flavan-3-ol (flavanols)

- Flavan-3-ols sử dụng khung 2-phenyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-chromen-3-ol.

- Catechin (C), Gallocatechin (GC), Catechin 3-gallate (Cg), Gallocatechin 3-gallate (GCg)), Epicatechin (Epicatechin (EC)), Epigallocatechin (EGC), Epicatechin 3-gallate (ECg), Epigallocatechin 3-gallate (EGCg).

- Theaflavin

- Thearubigin.

- Proanthocyanidin là các dimer, trimer, oligomer, hoặc polymer của các flavanol.

- Flavan-3-ols sử dụng khung 2-phenyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-chromen-3-ol.

Anthocyanidin[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- Anthocyanidins

- Anthocyanidin là aglycone của anthocyanin. Anthocyanidins sử dụng khung ion flavylium (2-phenylchromenylium).

- Các ví dụ: Cyanidin, Delphinidin, Malvidin, Pelargonidin, Peonidin, Petunidin

Isoflavonoid[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- Isoflavone sử dụng khung 3-phenylchromen-4-one (không có sự thay thế nhóm hydroxyl ở carbon vị trí số 2). Ví dụ: Genistein, Daidzein, Glycitein

- Isoflavane.

- Isoflavandiol.

- Isoflavene.

- Coumestan.

- Pterocarpan.

Nguồn thực phẩm[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Flavonoid (đặc biệt là các flavanoids như cathechin) là "nhóm phổ biến nhất trong các hợp chất polyphenolic có trong chế độ dinh dưỡng của con người và được tìm thấy khắp các loài thực vật".[7] Flavonol, như quercetin, cũng tìm thấy rộng rãi nhưng với lượng ít hơn. Sự phân bố rộng rãi của các flavonoid, cũng như đặc điểm đa dạng, độc tính tương đối thấp so với các hợp chất khác như alkaloid nên động vật, gồm cả con người có thể tiêu thụ một lượng đáng kể trong khẩu phần. Thực phẩm có hàm lượng flavonoid cao như yến sào, hành, việt quất và các berry khác, chuối, các loại quả có múi, vang đỏ, socola đen).[8]

Parsley Rau mùi tây[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Rau mùi tây tươi và khô đều chứa flavone.[8]

Blueberrie[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Việt quất có chứa anthocyanidin.[8][9]

Xem thêm[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Chú thích[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- ^ Mobh, Shiro (1938). “Research for Vitamin P”. The Journal of Biochemistry. 29 (3): 487–501.

- ^ McNaught, Alan D; Wilkinson, Andrew; IUPAC (1997). “IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology” (PDF) (ấn bản 2). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific. Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 29 tháng 6 năm 2011. Truy cập ngày 2 tháng 9 năm 2013. Chú thích journal cần

|journal=(trợ giúp);|contribution=bị bỏ qua (trợ giúp) - ^ flavonoids (isoflavonoids and neoflavonoids) IUPAC. Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book"). Compiled by A. D. McNaught and A. Wilkinson. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford (1997). XML on-line corrected version: http://goldbook.iupac.org (2006–) created by M. Nic, J. Jirat, B. Kosata; updates compiled by A. Jenkins. ISBN 0-9678550-9-8. doi:10.1351/goldbook. Last update: 2012-08-19; version: 2.3.2. DOI of this term: doi:10.1351/goldbook.F02424. (Original PDF version: http://www.iupac.org/goldbook/F02424.pdf. The PDF version is out of date and is provided for reference purposes only.) Retrieved ngày 16 tháng 9 năm 2012.

- ^ Galeotti, F; Barile, E; Curir, P; Dolci, M; Lanzotti, V (2008). “Flavonoids from carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus) and their antifungal activity”. Phytochemistry Letters. 1: 44. doi:10.1016/j.phytol.2007.10.001.

- ^ Ververidis Filippos, F (2007). Trantas Emmanouil, Douglas Carl, Vollmer Guenter, Kretzschmar Georg, Panopoulos Nickolas. “Biotechnology of flavonoids and other phenylpropanoid-derived natural products. Part I: Chemical diversity, impacts on plant biology and human health”. Biotechnology Journal. 2 (10): 1214–34. doi:10.1002/biot.200700084. PMID 17935117.

- ^ Isolation of a UDP-glucose: Flavonoid 5-O-glucosyltransferase gene and expression analysis of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.). Da Qiu Zhao, Chen Xia Han, Jin Tao Ge and Jun Tao, Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, ngày 15 tháng 11 năm 2012, Volume 15, Number 6, doi:10.2225/vol15-issue6-fulltext-7

- ^ Spencer JP (2008). “Flavonoids: modulators of brain function?”. British Journal of Nutrition. 99: ES60–77. doi:10.1017/S0007114508965776. PMID 18503736.

- ^ a b c Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>sai; không có nội dung trong thẻ ref có tênars.usda - ^ Ayoub M, de Camargo AC, Shahidi F (2016). “Antioxidants and bioactivities of free, esterified and insoluble-bound phenolics from berry seed meals”. Food Chemistry. 197 (Part A): 221–232. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.10.107.

Đọc thêm[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- Andersen, Ø.M. / Markham, K.R. (2006). Flavonoids: Chemistry, Biochemistry and Applications. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-2021-7

- Grotewold, Erich (2007). The Science of Flavonoids. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-74550-3

- Comparative Biochemistry of the Flavonoids, by J.B. Harborne, 1967 (Google Books)

- The systematic identification of flavonoids, by T.J. Mabry, K.R. Markham and M.B. Thomas, 1970, doi:10.1016/0022-2860(71)87109-0

Các liên kết ngoài[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- Flavonoids (chemistry) Lưu trữ 2005-02-04 tại Wayback Machine

- Micronutrient Information Center – Flavonoids

- Flavonoid Composition of Fruit Tissues of Citrus Species Lưu trữ 2007-05-28 tại Wayback Machine

Các dữ liệu[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- FlavonoidViewer.jp Lưu trữ 2013-05-30 tại Wayback Machine (Japanese, English), a database on flavonoids by Arita Group (Univ of Tokyo, RIKEN Plant Science Center, and Keio Univ), Nishioka Group (Kyoto and Keio Univ) and Kanaya Group (NAIST)

- USDA Database of Flavonoid content of food Lưu trữ 2012-07-16 tại Wayback Machine (pdf)