Thành viên:GDAE/Khai quật và cải táng vua Richard III của Anh

Vào tháng 9 năm 2012, hài cốt của Richard III, vị vua nước Anh cuối cùng bị giết trong trong chiến trận được phát hiện tại khuôn viên của Tu viện Grey Friars bị phá huỷ ở Leicester. Sau khi phân tích nhân chủng học và xét nghiệm di truyền, cuối cùng bộ hài cốt đã được hoả táng tại Nhà thờ Leicester vào ngày 26 tháng 3 năm 2015.

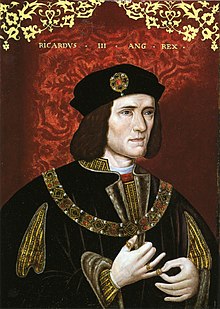

Richard III là người cai trị cuối cùng của vương triều Plantagenet. Ông bị giết vào ngày 22 tháng 8 năm 1485 trong Trận Bosworth, là trận chiến quan trọng cuối cùng của Chiến tranh Hoa Hồng. Thi thể của ông đã được đưa đến Greyfriars, Leicester và chỉ được chôn cất vội vàng trong một ngôi mộ thô sơ ở nhà thờ tu viện. Sau khi tu viện này giải thể vào năm 1538 và bị phá hủy sau đó, ngôi mộ của Richard cũng bị thất lạc. Có lời kể lại thiếu chính xác cho rằng bộ xương của Richard đã bị ném xuống dòng sông Soar ở cây cầu Bow gần đó.

Một cuộc tìm kiếm thi thể của Richard đã bắt đầu vào tháng 8 năm 2012 do dự án Looking for Richard (tạm dịch là "Tìm kiếm Richard") khởi xướng dưới sự hỗ trợ của Hiệp hội Richard III. Cuộc khai quật khảo cổ học này do Đại học ngành Khảo cổ học Leicester hợp tác với Hội đồng Thành phố Leicester cùng thực hiện. Ngay trong ngày đầu tiên của cuộc khai quật, một bộ xương người đàn ông khoảng ba mươi tuổi được phát hiện có dấu hiệu bị tổn hại. Bộ xương này có một số đặc điểm vật lý khác thường, đáng chú ý nhất là chứng vẹo cột sống, lưng bị cong nặng và sau đó được khai quật lên để phục vụ cho mục đích nghiên cứu khoa học. Khám nghiệm cho thấy người đàn ông này có thể đã bị giết bởi một cú đánh từ một vũ khí có lưỡi cắt lớn, có thể là một cái kích đã cắt một vết phía sau hộp sọ và làm lộ não của ông, hoặc bị giết bởi một nhát kiếm xuyên qua não. Các vết thương khác trên bộ xương có lẽ đã xảy ra sau khi chết, giống "vết thương nhục hình", vốn bị thực hiện như một hình thức trả thù sau khi chết.

Niên đại của bộ xương khi chết trùng khớp với tuổi của Richard khi ông bị giết; chúng được xác định niên đại vào khoảng thời gian ông qua đời và hầu hết đều phù hợp với những miêu tả về thể chất của nhà vua. Xét nghiệm di truyền sơ bộ cho thấy DNA ty thể được chiết xuất từ xương khớp với DNA của hai hậu duệ dòng nữ, một thế hệ thứ 17 và một thế hệ thứ 19 khác của chị gái Richard là Anne xứ York. Xem xét những phát hiện này cùng với các bằng chứng lịch sử, khoa học và khảo cổ học khác, vào ngày 4 tháng 2 năm 2013, Đại học Leicester thông báo họ đã kết luận nếu ngoài sự nghi ngờ có bằng chứng hợp lý thì bộ xương chính thức là của Richard III.

Với điều kiện được phép khai quật thi thể, các nhà khảo cổ đồng ý rằng nếu Richard được tìm thấy, thi thể của ông sẽ được cải táng tại Nhà thờ Leicester. Một cuộc tranh cãi dữ dội đã nảy lên về việc liệu một địa điểm cải táng thay thế khác như nhà thờ York Minster hay Tu viện Westminster sẽ phù hợp hơn. Ngoài ra, còn một thách thức pháp lý xác nhận rằng không có cơ sở luật công khai nào để các tòa án liên quan đến vụ việc có thể quyết định. Lễ cải táng diễn ra tại Leicester vào ngày 26 tháng 3 năm 2015, buổi lễ tưởng niệm trên truyền hình của sự kiện này được tổ chức với sự hiện diện của Tổng Giám mục Canterbury và các thành viên cao cấp của các giáo phái Cơ đốc giáo khác.

Cái chết và chôn cất ban đầu[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Richard III bị giết khi chiến đấu với lực lượng của Henry Tudor trong trận Bosworth năm 1485, trận chiến lớn cuối cùng trong Chiến tranh Hoa Hồng. Nhà thơ xứ Wales Guto'r Glyn cho rằng cái chết của Richard là do Rhys ap Thomas, một thành viên người Wales trong quân đội của Henry, người được cho là đã giáng một đòn chí mạng vào Richard bằng chiếc rìu chiến.[1] Richard III là vị vua Anh cuối cùng bị giết trong khi chiến đấu.[2]

Thi thể của Richard đã bị lột trần và đưa đến Leicester,[3][4] và còn bị phô bày trước công chúng. Một bài thơ truyền miệng vô danh "Ballad của trận Bosworth Field" nói rằng "ông được đặt ở Newarke, và nhiều người có thể dòm ngó vào ông" - dường như được khẳng định là ám chỉ tới đoàn thể Nhà thờ Lễ Truyền tin của Đức Mẹ Newarke,[5] một cơ sở do người Lancaster bản xứ thành lập ở ngoại ô Leicester thời trung cổ.[6] Theo người ghi chép sử biên niên Polydore Vergil, Henry VII đã "trì hoãn trong hai ngày" ở Leicester trước khi rời khởi Luân Đôn, và cùng ngày với sự rời đi của Henry — ngày 25 tháng 8 năm 1485 — thi thể của Richard được chôn cất "tại tu viện của các tu sĩ dòng Phanxicô ở Leicester" mà "không có nghi thức tang lễ nào".[7] Một linh mục và nhà khảo cổ học người Warwickshire là John Rous đã ghi chép lại khoảng từ năm 1486 đến năm 1491 rằng Richard đã được chôn cất với một "dàn đồng ca của các tu sĩ Dòng Anh Em Hèn Mọn tại Leicester".[7] Mặc dù các người viết văn kiện sau này cho rằng việc chôn cất Richard là ở những nơi khác, nhưng lời kể của Vergil và Rous được các nhà điều tra hiện đại xem là đáng tin cậy nhất.[8]

Địa điểm chôn cất[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Năm 1495, mười năm sau khi chôn cất, Henry VII đã trả tiền để mua một bia tưởng niệm bằng đá cẩm thạch và thạch cao tuyết hoa để đánh dấu vị trí ngôi mộ của Richard.[9] Chi phí cho việc xây dựng được ghi lại trong các văn kiện pháp lý còn tồn tại liên quan đến tranh chấp thanh toán, cho thấy hai người đàn ông đã nhận được khoản thanh toán lần lượt là 50 và 10,1 bảng Anh để làm và vận chuyển ngôi mộ từ Nottingham đến Leicester.[10] Không có lời miêu tả còn tồn tại của người tận mắt nào chứng kiến ngôi mộ, nhưng Raphael Holinshed đã viết vào năm 1577 (có lẽ trích dẫn lời một ai đó đã tận mắt nhìn thấy ngôi mộ) rằng nó kết hợp "một bức tranh về thạch cao miêu tả một người [Richard]".[11] 40 năm sau, nhà nghiên cứu đồ cổ George Buck miêu tả rằng đó là "một ngôi mộ đẹp bằng đá cẩm thạch pha trộn màu được trang trí với hình ảnh của ông".[11] Buck cũng ghi lại những dòng chữ khắc trên bia của ngôi mộ.[11]

Sau sự giải thể của tu viện Greyfriars vào năm 1538, tu viện này bị phá dỡ và bia tưởng niệm bị tổn hại hoặc mục nát từ từ do tiếp xúc với các yếu tố môi trường. Nơi đặt vị trí của tu viện đã được bán cho hai nhà đầu cơ bất động sản người Lincolnshire và sau đó được Robert Herrick, thị trưởng của Leicester (và cuối cùng là chú của nhà thơ Robert Herrick) mua lại. Thị trưởng Herrick đã xây dựng một dinh thự gần Friary Lane, trên một khu đất hiện bị chôn vùi dưới Phố Grey Friars ngày nay, và biến phần đất còn lại thành những khu vườn.[12] Mặc dù bia tưởng niệm của Richard đã biến mất hiển nhiên vào thời điểm này, nhưng nơi đặt vị trí của ngôi mộ Richard vẫn được biết đến. Nhà khảo cổ Christopher Wren (cha của Christopher Wren, một kiến trúc sư) ghi lại rằng Herrick đã dựng một bia tưởng niệm trên vị trí đặt ngôi mộ dưới dạng một cột đá cao 3 feet (1 m) có khắc dòng chữ, "Đây là nơi đặt thi thể của Richard III, người từng là vua nước Anh."[13] Cây cột được nhìn thấy vào năm 1612, nhưng đã biến mất vào năm 1844.[14]

Nhà vẽ bản đồ và khảo cổ học John Speed đã viết trong cuốn Historie of Great Britain năm 1611 của mình rằng truyền thống địa phương nói thi thể của Richard đã được "mang ra từ thành phố, và bị đặt một cách khinh bỉ dưới cuối Cầu Bow, nơi có lối đi qua một nhánh của sông Soar ở phía tây của thị trấn."[15] Lời kể lại của ông đã được chấp nhận rộng rãi bởi các tác giả sau này. Năm 1856, một tấm bảng tưởng niệm Richard III đã được một người thợ xây dựng ở địa phương dựng lên bên cạnh Cầu Bow, trong đó ghi rằng "Gần vị trí này có hài cốt của Richard III, người cuối cùng của triều Plantagenets 1485".[16] Việc phát hiện ra một bộ xương vào năm 1862 trong lớp trầm tích sông gần cây cầu đã dẫn đến tuyên bố rằng hài cốt của Richard đã được tìm thấy, nhưng qua khám nghiệm kỹ hơn cho thấy bộ xương này có thể là của một người đàn ông ở độ tuổi 20 chứ không phải của Richard.[16]

Nguồn gốc tuyên bố của Speed là không rõ ràng khi nó không được trích dẫn từ bất kỳ nguồn nào, cũng như không có bất kỳ chứng cứ lịch sử nào trong các lời kể lại bằng văn bản khác.[16] Nhà văn Audrey Strange ám chỉ rằng sự việc này có thể là một lời kể lại nhầm lẫn về việc xâm phạm hài cốt của John Wycliffe ở Lutterworth gần đó vào năm 1428, khi một đám đông đào mộ, đốt thi thể của ông và ném chúng xuống sông Swift.[17] Nhà sử học độc lập người Anh John Ashdown-Hill cho rằng Speed đã nhầm lẫn vị trí ngôi mộ của Richard và bịa ra câu chuyện để giải thích cho sự sai xót đó. Nếu Speed đến cơ ngơi của Herrick, chắc chắn ông sẽ nhìn thấy bia tưởng niệm và những khu vườn, nhưng thay vào đó ông cho rằng địa điểm này bị "cây tầm ma và cỏ dại mọc um tùm"[18] và không có dấu vết nào về ngôi mộ của Richard. Bản đồ vẽ Leicester của Speed không chính xác cho thấy vị trí Blackfriars (tu viện Greyfriars cũ), cho thấy ông đã tìm kiếm ngôi mộ không đúng chỗ.[18]

Một truyền thuyết địa phương khác dựng lên rằng một quan tài đá được cho là nơi chứa hài cốt của Richard, mà Speed viết viết "giờ đây được làm máng uống nước cho ngựa tại một lữ quán bình dân". Một chiếc quan tài chắc chắn dường như đã tồn tại: John Evelyn đã ghi chép trong một chuyến viếng thăm vào năm 1654, và Celia Fiennes viết vào năm 1700 rằng bà đã nhìn thấy "một mảnh bia mộ của mà ông ấy [Richard] nằm, được cắt theo hình dạng chính xác để chứa thi thể; chiếc quan tài vẫn còn nguyên được nhìn thấy tại Greyhound [lữ quán] ở Leicester nhưng đã bị vỡ một phần." Năm 1758, William Hutton tìm thấy chiếc quan tài "không còn chống cự được khỏi sự mài mòn của thời gian", được lưu giữ tại White Horse Inn trên Cổng Gallowtree. Mặc dù vị trí của chiếc quan tài không còn được biết đến, nhưng mô tả về nó không phù hợp với hình mẫu những chiếc quan tài cuối thế kỷ 15, và dường như không có mối liên hệ nào với Richard. Nhiều khả năng chiếc quan tài được lấy ra khỏi từ một trong những cơ sở tôn giáo bị phá bỏ sau khi sự kiện giải thể.[16]

Dinh thự của Herrick, Greyfriars House, vẫn thuộc quyền sở hữu của gia đình ông cho đến khi chắt trai của ông là Samuel đã thanh lý dinh thự vào năm 1711. Khối tài sản sau đó được phân chia và bán vào năm 1740 và ba năm sau, New Street được xây dựng trên phần phía Tây của vị trí dinh thự. Nhiều cuộc chôn cất được phát hiện khi các ngôi nhà được giải phóng mặt bằng dọc theo đường phố. Một ngôi nhà phố có địa chỉ số 17 Friar Lane được xây dựng ở phần phía đông của địa điểm vào năm 1759 và tồn tại cho đến ngày nay. Trong thế kỷ 19, địa điểm này ngày càng được xây dựng thêm nhiều công trình hơn. Năm 1863 Trường nam sinh Alderman Newton được khởi công xây dựng một trường sở trên một phần của vị trí này. Biệt thự của Herrick bị dỡ bỏ vào năm 1871, Đường Grey Friars ngày nay được xây dựng thông qua địa điểm này vào năm 1873, và nhiều công trình thương mại khác, bao gồm cả Ngân hàng Tiết kiệm Tín nhân Leicester cũng được xây dựng. Vào năm 1915, phần còn lại của vị trí này đã được mua lại bởi Hội đồng hạt Leicestershire, nơi mà văn phòng được xây dựng trên đó vào thập niên những năm 1920 và 1930. Hội đồng của hạt này đã di dời trụ sở vào năm 1965 khi Tòa thị chính mới của địa phương mở cửa và Hội đồng thành phố Leicester chuyển đến.[16] Phần còn lại của vị trí này, nơi từng là khu vườn của Herrick đã được trưng dụng làm bãi đậu xe của nhân viên vào khoảng năm 1944, nếu không cũng sẽ không được xây dựng thêm gì.[19]

In 2007, a single-storey building from the 1950s was demolished on Grey Friars Street giving archaeologists the opportunity to excavate and search for traces of the medieval friary. Very little was unearthed, except for a fragment of a post-medieval stone coffin lid. The results of the dig suggested that the remains of the friary church were farther west than previously thought.[20]

Looking for Richard project[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The location of Richard III's body had long been of interest to the members of the Richard III Society, a group established to bring about a reappraisal of the King's tarnished reputation. In 1975 an article by Audrey Strange was published in the society's journal, The Ricardian, suggesting that his remains were buried under Leicester City Council's car park.[21] The claim was repeated in 1986, when historian David Baldwin suggested that the remains were still in the Greyfriars area.[22] He speculated, "It is possible (though now perhaps unlikely) that at some time in the twenty-first century an excavator may yet reveal the slight remains of this famous monarch."[23]

Although the Richard III Society remained interested in discussing the possible location of the king's grave, they did not search for his remains. Individual members suggested possible lines of investigation, but neither the University of Leicester nor local historians and archaeologists took up the challenge, probably because it was widely thought that the grave site had been built over or the skeleton had been scattered, as John Speed's account suggested.[24]

In 2004 and 2005, Philippa Langley, secretary of the Scottish Branch of the Richard III Society, carried out research in Leicester in connection with a biographical Richard III screenplay and became convinced that the car park was the key location for investigation.[25] In 2005, John Ashdown-Hill announced that he had discovered the mitochondrial DNA sequence of Richard III after identifying two matrilineal descendants of Richard III's sister Anne of York.[26] He also concluded, from his knowledge of the layout of Franciscan priories, that the ruins of the priory church at Greyfriars were likely to lie under the car park and had not been built over.[27] After hearing of his research, Langley urged Ashdown-Hill to contact the producers of Channel 4's Time Team archaeology series to propose an excavation of the car park, but they declined as the dig would take longer than the standard three-day window for Time Team projects.

Three years later, writer Annette Carson, in her book Richard III: The Maligned King (the History Press 2008, 2009, page 270), published her independent conclusion that his body probably lay under the car park. She joined forces with Langley and Ashdown-Hill to carry out further research.[28] By now Langley had found what she called a "smoking gun"—a medieval map of Leicester showing the Greyfriars Church at the north end of what was now the car park.[29]

In February 2009, Langley, Carson and Ashdown-Hill teamed up with Richard III Society members David Johnson and his wife Wendy to launch a project with the working title Looking for Richard: In Search of a King. Its premise was a search for Richard's grave "while at the same time telling his real story",[20][30] with an objective "to search for, recover and rebury his mortal remains with the honour, dignity and respect so conspicuously denied following his death at the battle of Bosworth."[31] To ensure support from decision makers in Leicester, Langley had secured interest from Darlow Smith Productions for a televised documentary, which Langley envisaged as a "landmark TV special".[20]

The project gained the backing of several key partners—Leicester City Council, Leicester Promotions (responsible for tourist marketing), the University of Leicester, Leicester Cathedral, Darlow Smithson Productions (responsible for the planned TV show) and the Richard III Society.[30] Funding for the initial phase of pre-excavation research came from the Richard III Society's bursary fund and members of the Looking for Richard project,[32] with Leicester Promotions agreeing to pick up the £35,000 cost of the dig. The University of Leicester Archaeological Services—an independent body with offices at the university—was appointed as the project's archaeological contractor.[33]

Greyfriars project and excavations[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In March 2011 an assessment of the Greyfriars site began to identify where the monastery had stood, and which land might be available for excavation. A desk-based assessment[note 1] was conducted to determine the archaeological viability of the site, followed by a survey in August 2011 using ground-penetrating radar (GPR).[20] The GPR results were inconclusive; no clear building remains could be identified owing to a layer of disturbed ground and demolition debris just below the surface. The survey was useful in finding modern utilities crossing the site, such as pipes and cables.[34]

Three possible excavation sites were identified: the staff car park of Leicester City Council Social Services, the disused playground of the former Alderman Newton's School and a public car park on New Street. It was decided to open two trenches in the Social Services car park, with an option for a third in the playground.[35] Because most of the Greyfriars site had been built on, only seventeen per cent of its former area was available to excavate; the area to be investigated amounted to just one per cent of the site, owing to the limitations of the project's funding.[36]

The proposed excavation was announced in the June 2012 issue of the Richard III Society's magazine, the Ricardian Bulletin, but a month later one of the main sponsors pulled out, leaving a £10,000 funding shortfall; an appeal resulted in members of the several Ricardian groups donating £13,000 in two weeks.[37] A press conference held in Leicester on 24 August announced the start of the work. Archaeologist Richard Buckley admitted the project was a long shot: "We don't know precisely where the church is, let alone where the burial site is."[38] He had earlier told Langley that he thought the odds were "fifty-fifty at best for [finding] the church, and nine-to-one against finding the grave."[39]

Digging began the next day with a trench 1,6 mét (5,2 ft) wide by 30 mét (98 ft) long, running roughly north-south. A layer of modern building debris was removed before the level of the former monastery was reached. Two parallel human leg bones were discovered about 5 mét (16 ft) from the north end of the trench at a depth of about 1,5 mét (4,9 ft), indicating an undisturbed burial.[40] The bones were covered temporarily to protect them while excavations continued further along the trench. A second, parallel trench was dug next day to the south-west.[41] Over the following days, evidence of medieval walls and rooms was uncovered, allowing the archaeologists to pinpoint the area of the friary.[42] It became clear that the bones found on the first day lay inside the east part of the church, possibly the choir, where Richard was said to have been buried.[43] On 31 August, the University of Leicester applied for a licence from the Ministry of Justice to permit the exhumation of up to six sets of human remains. To narrow the search, it was planned that only the remains of men in their thirties, buried within the church, would be exhumed.[42]

The bones found on 25 August were uncovered on 4 September and the grave soil dug back further over the next two days. The feet were missing, and the skull was found in an unusual propped-up position, consistent with the body being put into a grave that was slightly too small.[44] The spine was curved in an S-shape. No sign of a coffin was found; the skeleton's posture suggested the body had not been put in a shroud, but had been hurriedly dumped into the grave and buried. As the bones were lifted from the ground, a piece of rusted iron was found underneath the vertebrae.[45][46] The skeleton's hands were in an unusual position, crossed over the right hip, suggesting they were tied together at the time of burial, although this could not be established definitively.[47] After the exhumation, work continued in the trenches over the following week, before the site was covered with soil to protect it from damage and re-surfaced to restore the car park and playground to their former condition.[48]

Analysis of the discovery[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

On 12 September, the University of Leicester team announced that the human remains were a possible candidate for Richard's body, but emphasised the need for caution. The positive indicators were that the body was of an adult male; it was buried beneath the choir of the church; it had severe scoliosis of the spine possibly making one shoulder higher than the other.[49] An object that appeared to be an arrowhead was found under the spine and the skull had severe injuries.[50][51]

DNA evidence[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

After the exhumation the emphasis shifted from the excavation to laboratory analysis of the bones that had been recovered. Ashdown-Hill had used genealogical research to track down matrilineal descendants of Anne of York, Richard's older sister, whose matrilineal line of descent is extant through her daughter Anne St Leger. Academic Kevin Schürer subsequently traced a second individual in the same line.[52]

Ashdown-Hill's research came about as a result of a challenge in 2003 to provide a DNA sequence for Richard's sister Margaret, to identify bones found in her burial place, the Franciscan priory church in Mechelen, Belgium. He tried to extract a mitochondrial DNA sequence from a preserved hair from Edward IV held by the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford but the attempt proved unsuccessful, owing to degradation of the DNA. Ashdown-Hill turned instead to genealogical research to identify an all-female-line descendant of Cecily Neville, Richard's mother.[53] After two years he found a British-born woman who had emigrated to Canada after World War II, Joy Ibsen (née Brown), was a direct descendant of Richard's sister, Anne of York (and therefore Richard's 16th generation great-niece).[54][55] Ibsen's mitochondrial DNA was tested and found to belong to mitochondrial DNA Haplogroup J, which by deduction should be Richard's mitochondrial DNA haplogroup.[56] The mtDNA obtained from Ibsen showed that the Mechelen bones were not those of Margaret.[53]

Joy Ibsen, a retired journalist, died in 2008, leaving three children: Michael, Jeff, and Leslie.[58] On 24 August 2012, her son Michael (born in Canada in 1957, a cabinet maker based in London, United Kingdom)[59][60] gave a mouth-swab sample to the research team to compare with samples from the human remains found at the excavation.[61] Analysts found a mitochondrial DNA match among the exhumed skeleton, Michael Ibsen, and a second direct maternal line descendant, who shares a relatively rare mitochondrial DNA sequence,[62][63][64] mitochondrial DNA haplogroup J1c2c.[65][66]

The other living female-line relative of Richard III is Wendy Duldig, an Australian resident in England and a 19th generation descendant of Anne of York. Duldig, who has no surviving children, is connected to the Ibsen family through Anne's granddaughter Catherine Constable, née Manners. Descendants of Constable, including one of Duldig's ancestors reportedly emigrated to New Zealand. Duldig's mitochondrial DNA is reportedly a close match, i.e. it features one mutation.[54]

Despite the matching mitochondrial DNA, geneticist Turi King continued to pursue a link between the paternally-inherited Y DNA and that of descendants of John of Gaunt. Four living male-line descendants of Gaunt have been located, and their results are a match to each other. The Y DNA from the skeleton is somewhat degraded, but proved not to match any of the living male-line relatives, showing that a false-paternity event had happened somewhere in the 19 generations between Richard III and Henry Somerset, 5th Duke of Beaufort; work by Turi King and others has shown that historical rates of false paternity are around 1–2% per generation.[62]

Professor Michael Hicks, a Richard III specialist, has been particularly critical of the use of the mitochondrial DNA to argue that the body is Richard III's, stating that "any male sharing a maternal ancestress in the direct female line could qualify". He also criticises the rejection by the Leicester team of the Y chromosomal evidence, suggesting that it was not acceptable to the Leicester team to conclude that the skeleton was anyone other than Richard III. He argues that on the basis of the present scientific evidence "identification with Richard III is more unlikely than likely". However, Hicks himself draws attention to the contemporary view held by some that Richard III's grandfather, Richard, Earl of Cambridge, was the product of an illegitimate union between Cambridge's mother Isabella of Castile and John Holland (brother in law of Henry IV of England), rather than Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York (Edward III's fourth son). If that was the case then the Y chromosome discrepancy with the Beaufort line would be explained but obviously still fail to prove the identity of the body. Hicks suggests alternative candidates descended from Richard III's maternal ancestress for the body (e.g. Thomas Percy, 1st Baron Egremont, and John de la Pole, 1st Earl of Lincoln) but does not provide evidence to support his suggestions. Philippa Langley refutes Hicks's argument on the grounds that he does not take into account all the evidence.[67][68]

Bones[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

An osteological examination of the bones by Jo Appleby showed them to be in generally good condition and largely complete except for the missing feet, which may have been destroyed by Victorian building work. It was immediately apparent that the body had suffered major injuries, and further evidence of wounds was found as the skeleton was cleaned.[47] The skull shows signs of two lethal injuries; the base of the back of the skull had been completely cut away by a bladed weapon, which would have exposed the brain, and another bladed weapon had been thrust through the right side of the skull, striking the inside of the left side through the brain.[69] Elsewhere on the skull, a blow from a pointed weapon had penetrated the crown of the head. Bladed weapons had clipped the skull and sheared off layers of bone, without penetrating it.[70] Other holes in the skull and lower jaw were found to be consistent with dagger wounds to the chin and cheek.[71] The multiple wounds on the king’s skull indicated that he was not wearing his helmet at the time, which he may have either removed or lost when he was on foot after his horse had become stuck in the marsh.[72][73] One of his right ribs had been cut by a sharp implement, as had the pelvis.[74] There was no evidence of the withered arm that afflicted the character in William Shakespeare's play Richard III.[75][76]

Taken together, the injuries appear to be a combination of battle wounds, which were the cause of death, followed by post-mortem humiliation wounds inflicted on the corpse. The body wounds show that the corpse had been stripped of its armour, as the stabbed torso would have been protected by a backplate and the pelvis would have been protected by armour. The wounds were made from behind on the back and buttocks while they were exposed to the elements, consistent with the contemporary descriptions of Richard's naked body being tied across a horse with the legs and arms dangling down on either side.[71][74][77] There may have been further flesh wounds not apparent from the bones.[75]

The head wounds are consistent with the narrative of a 1485 poem by Guto'r Glyn in which a Welsh knight, Sir Rhys ap Thomas, killed Richard and "shaved the boar's head".[78] It had been thought that this was a figurative description of Richard being decapitated, but the skeleton's head had clearly not been severed. Guto's description may instead be a literal account of the injuries that Richard suffered, as the blows sustained to the head would have sliced away much of his scalp and hair, along with slivers of bone.[78] Other contemporary sources refer explicitly to head injuries and the weapons used to kill Richard; the French chronicler Jean Molinet wrote that "one of the Welshmen then came after him, and struck him dead with a halberd", and the Ballad of Lady Bessie recorded that "they struck his bascinet to his head until his brains came out with blood." Such accounts would certainly fit the damage inflicted on the skull.[77][79]

Sideways curvature of his spine was evident as the skeleton was excavated. It has been attributed to adolescent-onset scoliosis. Although it was probably visible in making his right shoulder higher than the left and reducing his apparent height, it did not preclude an active lifestyle, and would not have caused what modern medicine describes as a "hunchback".[80] The bones are those of a male with an age range estimation of 30–34,[73] consistent with Richard, who was 32 when he died.[75]

Radiocarbon dating and other scientific analyses[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Two radiocarbon datings to find the age of the bones suggested dates of 1430–1460[note 2] and 1412–1449[note 3] – both too early for Richard's death in 1485. Mass spectrometry carried out on the bones found evidence of much seafood consumption, which is known to make radiocarbon dating samples appear older than they are. A Bayesian analysis suggested there was a 68.2% probability that the true date of the bones was between 1475–1530, rising to 95.4% for 1450–1540. Although by itself not enough to prove that the skeleton was Richard's, it was consistent with the date of his death.[81] The mass spectrometry result indicating the rich seafood diet was confirmed by a chemical isotope analysis of two teeth, a femur, and a rib. From the isotope analysis of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen in the teeth and bones the researchers discovered the diet included much freshwater fish and exotic birds such as swan, crane, and heron, and a vast quantity of wine – all items at the high end of the luxury market.[82] Close analysis of the soil immediately below the skeleton revealed that the man had been infested with roundworm parasites when he died.[83]

The excavators found an iron object under the skeleton's vertebrae and speculated it might be an arrowhead that had been embedded in its back. An X-ray analysis showed it was a nail, probably dating to Roman Britain, that had been in the ground by chance immediately under the grave, or was in soil disturbed when the grave was dug, and had nothing to do with the body.[75]

Identification of Richard III and other findings[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

On 4 February 2013, the University of Leicester confirmed that the skeleton was that of Richard III.[84][85][86] The identification was based on mitochondrial DNA evidence, soil analysis, dental tests, and physical characteristics of the skeleton consistent with contemporary accounts of Richard's appearance. Osteoarchaeologist Jo Appleby commented: "The skeleton has a number of unusual features: its slender build, the scoliosis, and the battle-related trauma. All of these are highly consistent with the information that we have about Richard III in life and about the circumstances of his death."[84]

Caroline Wilkinson, Professor of Craniofacial Identification at the University of Dundee, led the project to reconstruct the face, commissioned by the Richard III Society.[87] On 11 February 2014, the University of Leicester announced a project headed by Turi King to sequence the entire genome of Richard III and Michael Ibsen—a direct female-line descendant of Richard's sister, Anne of York—whose mitochondrial DNA confirmed the identification of the excavated remains. Richard III is thus the first ancient person with known historical identity whose genome has been sequenced.[88] A study published in Nature Communications in December 2014 confirmed a perfect whole-mitochondrial genome match between Richard's skeleton and Michael Ibsen and a near-perfect match between Richard and his other confirmed living relative. However, Y chromosome DNA inherited via the male line found no link with five other claimed living relatives, indicating that at least one "false-paternity event" occurred in the generations between Richard and these men. One of these five was found to be unrelated to the other four, showing that another false-paternity event had occurred in the four generations separating them.[89]

The story of the excavation and subsequent scientific investigation was told in a Channel 4 documentary, Richard III: The King in the Car Park, broadcast on 4 February 2013.[90] It proved a ratings hit for the channel, watched by up to 4.9 million viewers,[91] and won a Royal Television Society award.[92] Channel 4 subsequently screened a follow-up documentary on 27 February 2014, Richard III: The Untold Story, which detailed the scientific and archaeological analyses that led to the identification of the skeleton as Richard III.[91]

The site was re-excavated in July 2013 to learn more about the friary church, before building work on the adjacent disused school building. In a project co-funded by Leicester City Council and the University of Leicester, a single trench about twice the area of the 2012 trenches was excavated. It succeeded in exposing the entirety of the sites of the Greyfriars presbytery and choir sites, confirming archaeologists' earlier hypotheses about the layout of the church's east end. Three burials identified but not excavated in the 2012 project were tackled afresh. One burial was found to have been interred in a wooden coffin in a well-dug grave, while a second wooden-coffined burial was found under and astride the choir and presbytery; its position suggests that it pre-dates the church.[93]

A stone coffin found during the 2012 excavation was opened for the first time, revealing a lead coffin inside. An investigation with an endoscope revealed the presence of a skeleton along with some head hair and fragments of a shroud and cord.[93] The skeleton was at first assumed to be male, perhaps that of a knight called Sir William de Moton who was known to have been buried there, but later examination showed it to be of a woman—perhaps a high-ranking benefactor.[94] She may not necessarily have been local, as lead coffins were used to transport corpses over long distances.[93]

Plans and challenges[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The University of Leicester's plan to inter Richard's body in Leicester Cathedral was in keeping with British legal norms which hold that Christian burials excavated by archaeologists should be reburied in the nearest consecrated ground to the original grave[83] and was a condition of the licence granted by the Ministry of Justice to exhume any human remains found during the excavation.[95] The British royal family made no claim on the remains – Queen Elizabeth II was reportedly consulted but rejected the idea of a royal burial[83] – so the Ministry of Justice initially confirmed that the University of Leicester would make the final decision on where the bones should be re-buried.[96] David Monteith, Canon Chancellor of Leicester Cathedral, said Richard's skeleton would be reinterred at the cathedral in early 2014 in a "Christian-led but ecumenical service",[97] not a formal reburial but rather a service of remembrance, as a funeral service would have been held at the time of burial.[98]

The choice of burial site proved controversial and proposals were made for Richard to be buried in places which some felt were more fitting for a Roman Catholic and Yorkist monarch. Online petitions were launched calling for Richard to be buried in Westminster Abbey,[note 4] where 17 other English and British kings are interred; York Minster, which some claimed was Richard's own preferred burial site; the Roman Catholic Arundel Cathedral; or in the Leicester car park in which his body was found. Only two options received significant public support, with Leicester receiving 3,100 more signatures than York.[83] The issue was discussed in the Houses of Parliament; the Conservative MP and historian Chris Skidmore proposed that a state funeral should be held, while John Mann, the Labour MP for Bassetlaw, suggested that the body should be buried in Worksop in his constituency—halfway between York and Leicester. All options were rejected in Leicester, whose mayor Peter Soulsby retorted: "Those bones leave Leicester over my dead body."[100]

After legal action brought by the "Plantagenet Alliance", a group representing claimed descendants of Richard's siblings, his final resting place remained uncertain for nearly a year.[101] The group, which described itself as "his Majesty's representatives and voice",[93] called for Richard to be buried in York Minster, which they claimed was his "wish".[101][102] The Dean of Leicester called their challenge "disrespectful", and said that the cathedral would not invest any more money until the matter was decided.[103] Historians said there was no evidence that Richard III wanted to be buried in York.[93] Mark Ormrod of the University of York expressed scepticism over the idea that Richard had devised any clear plans for his own burial.[104] The standing of the Plantagenet Alliance was challenged. Mathematician Rob Eastaway calculated that Richard III's siblings may have millions of living descendants, saying that "we should all have the chance to vote on Leicester versus York".[105]

In August 2013 Mr. Justice Haddon-Cave granted permission for a judicial review since the original burial plans ignored the common law duty "to consult widely as to how and where Richard III's remains should appropriately be reinterred".[102] The judicial review opened on 13 March 2014 and was expected to last two days[106] but the decision was deferred for four to six weeks. Lady Justice Hallett, sitting with Mr. Justice Ouseley and Justice Haddon-Cave, said the court would take time to consider its judgment.[107] On 23 May the High Court ruled there was "no duty to consult" and "no public law grounds for the court to interfere", so reburial in Leicester could proceed.[108] The litigation cost the defendants £245,000 – far more than the cost of the original investigation.[83]

Reburial and commemorations[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In February 2013, Leicester Cathedral announced a procedure and timetable for the reinterment of Richard's remains. The cathedral authorities planned to bury him in a "place of honour" within the cathedral.[109] Initial plans for a flat ledger stone, perhaps modifying the memorial stone installed in the chancel in 1982,[110] proved unpopular. A table tomb was the most popular option among members of the Richard III Society and in polls of Leicester people.[111][112] In June 2014 the design was announced, in the form of a table tomb of Swaledale fossil stone on a Kilkenny marble plinth.[113] That month, the statue of Richard III that had stood in Leicester's Castle Gardens was moved to the redesigned Cathedral Gardens, which were reopened on 5 July 2014.[114]

The reburial took place during a week of events between 22 and 27 March 2015. The sequence of events included:

- Sunday 22 March 2015: Richard's bones were sealed in a lead-lined ossuary and placed in a wooden coffin.[115] The remains were moved from the University of Leicester to Leicester Cathedral via the site of the Battle of Bosworth at Fenn Lane Farm and through Dadlington, Sutton Cheney, Bosworth Battlefield Heritage Centre on Ambion Hill, and Market Bosworth retracing part of Richard's last journey.[83][116] The coffin, made from English oak from the Duchy of Cornwall estate by Michael Ibsen,[60] was transferred from a motor hearse to a four-horse-drawn hearse for entry into the city of Leicester.[117]

- Monday 23 – Wednesday 25 March 2015: Remains lay in repose in the cathedral. Waiting times to view the coffin were reported to exceed four hours.[118]

- Monday 23 March 2015: Cardinal Vincent Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster, celebrated Mass for Richard III's soul in Holy Cross Priory, Leicester, the Catholic parish church, and in Holy Cross Church.

- Thursday 26 March 2015: Reburial in the presence of Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury, and senior members of other Christian denominations. The service, shown live on Channel 4, included memorial prayers for Richard III and the victims of Bosworth and other conflicts. Actor Benedict Cumberbatch, a distant relative of Richard III, who would soon portray him in the BBC Shakespeare adaptation The Hollow Crown,[119] read a poem written for the service by the poet laureate, Carol Ann Duffy.[120][121] The royal family was represented by Sophie, Countess of Wessex, Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and Birgitte, Duchess of Gloucester—Richard III was Duke of Gloucester before his accession. Music during the service included a setting of Psalm 138 by Leonel Power; Ghostly Grace, an anthem composed for the service by Judith Bingham; a setting of Psalm 150 by Philip Moore; and an arrangement of "God Save the Queen" by Judith Weir.[122]

- Friday 27 March 2015: Unveiling the tomb to the public, in a Service of Reveal at Leicester Cathedral, followed by commemorations across Leicester.[123]

Reactions[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

After the discovery, Leicester City Council set up a temporary exhibition about Richard III in the city's medieval guildhall.[124] The council announced it would create a permanent attraction and subsequently spent £850,000 to buy the freehold of St Martin's Place, formerly part of Leicester Grammar School, in Peacock Lane, across the road from the cathedral. The site adjoins the car park where the body was found, and overlies the chancel of Greyfriars Friary Church.[100][125] It was converted into the £4.5 million King Richard III Visitor Centre, telling the story of Richard's life, death, burial and rediscovery, with artefacts from the dig including Philippa Langley's Wellington boots and the hard hat and high-visibility jacket worn by archaeologist Mathew Morris on the day he found Richard's skeleton. Visitors can see the grave site under a glass floor.[126] The council anticipated that the visitor centre, which opened in July 2014, would attract 100,000 visitors a year.[124]

In Norway, archaeologist Øystein Ekroll hoped that the interest in the discovery of the English king would spill over to Norway. In contrast to England where, with the possible exceptions of Henry I, and Edward V, all the gravesites of English and British monarchs since the 11th century have now been discovered, in Norway about 25 medieval kings are buried in unmarked graves around the country. Ekroll proposed to start with Harald Hardrada, who was probably buried anonymously in Trondheim, beneath what is today a public road. A previous attempt to exhume Harald in 2006 was blocked by the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage (Riksantikvaren).[127]

Richard Buckley of the University of Leicester Archaeological Services, who said he would "eat his hat" if Richard was discovered, fulfilled his promise by eating a hat-shaped cake baked by a colleague.[98] Buckley later said:

Cutting-edge research has been used in the project and the work has really only just begun. The discoveries, such as the very precise carbon dating and medical evidence, will serve as a benchmark for other studies. And it is, of course, an incredible story. He's a controversial figure; people love the idea he was found under a car park; the whole thing unfolded in the most amazing way. You couldn't make it up.[128]

Some commentators suggested the discovery and subsequent positive exposure and good morale around the city contributed to Leicester City F.C.'s shock Premier League victory in 2016. A few days after the burial, Leicester City began a winning streak to take them from bottom of the league to comfortably avoiding relegation, and they went on to win the league the following year. Mayor Peter Soulsby said:

For too long, people in Leicester have been modest about their achievements and the city they live in. Now – thanks first to the discovery of King Richard III and the Foxes' phenomenal season – it's our time to step into the international limelight.[129]

The two events inspired Michael Morpurgo's 2016 children's book, The Fox and the Ghost King, in which the ghost of Richard III promises to help the football team in return for being released from his car park grave.[130]

In popular culture[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- Directed by Stephen Frears, the upcoming British comedy-drama film The Lost King follows Philippa Langley's search for King Richard III's body.[131]

Notes[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- ^ A desk-based assessment involves gathering together the written, graphic, photographic and electronic information that already exists about a site to help identify the likely character, extent, and quality of the known or suspected remains or structures being researched.

- ^ Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (SUERC)

- ^ University of Oxford's Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit

- ^ Richard's wife Anne Neville is buried within Westminster Abbey; it is uncertain where their only child Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales, is buried; theories have included Sheriff Hutton Church, or Middleham, both in North Yorkshire.[99]

References[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- ^ Rees (2008), tr. 212.

- ^ “King Richard III killed by blows to skull”. BBC News. London. 17 tháng 9 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 3 tháng 12 năm 2014.

- ^ Hipshon (2009), tr. 25.

- ^ Rhodes (1997), tr. 45.

- ^ “The Newarke and the Church of the Annunciation”. University of Leicester. Truy cập ngày 27 tháng 3 năm 2015.

- ^ Morris & Buckley, p. 22.

- ^ a b Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 8.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 19.

- ^ Baldwin (1986), tr. 21–22.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 17.

- ^ Morris & Buckley, p. 26.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 20.

- ^ Halsted (1844), tr. 401.

- ^ Morris & Buckley, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e Morris & Buckley, p. 29.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 22.

- ^ a b Langley & Jones (2014), tr. 7, 10.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, pp. 35, 46.

- ^ a b c d Langley, Philippa (tháng 6 năm 2012). “The Man Himself: Looking for Richard: In Search of a King”. Ricardian Bulletin. Richard III Society: 26–28.

- ^ Strange, Audrey (tháng 9 năm 1975). “The Grey Friars, Leicester”. The Ricardian. Richard III Society. 3 (50): 3–7.

- ^ Baldwin (1986), tr. 24.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 25.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 31.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 32.

- ^ Langley & Jones (2014), tr. 11.

- ^ a b “Meet Philippa Langley: the woman who discovered Richard III in a car park”. Radio Times. 2 tháng 4 năm 2013. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 25 tháng 3 năm 2015. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 36.

- ^ Langley & Jones (2014), tr. 22, 26.

- ^ Langley & Jones (2014), tr. 21, 24.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 48.

- ^ “Where we dug”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Langley & Jones (2014), tr. 56.

- ^ Langley, Philippa (tháng 9 năm 2012). “Update: Looking for Richard: In Search of a King”. Ricardian Bulletin. Richard III Society: 14–15.

- ^ Rainey, Sarah (25 tháng 8 năm 2012). “Digging for dirt on the Hunchback King”. The Daily Telegraph. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 26 tháng 8 năm 2012. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Langley & Jones (2014), tr. 21.

- ^ “Saturday 25 August 2012”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Sunday 26 August 2012”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ a b “Monday 27 to Friday 31 August 2012”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “1 September”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Lead archaeologist Richard Buckley gives key evidence from the dig site”. University of Leicester. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Wednesday 5 September 2012”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Wednesday 5 September 2012 (continued)”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013.

- ^ a b “Osteology”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Saturday 8 to Friday 14 September 2012”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Richard III Society pays tribute to exemplary archaeological research”. University of Leicester. 15 tháng 10 năm 2012. Truy cập ngày 12 tháng 2 năm 2013.

- ^ “Richard III dig: Eyes of world on Leicester as Greyfriars skeleton find revealed”. Leicester Mercury. 13 tháng 9 năm 2012. Bản gốc lưu trữ 8 Tháng hai năm 2013. Truy cập 23 Tháng hai năm 2015.

- ^ Wainwright, Martin (13 tháng 9 năm 2012). “Richard III: Could the skeleton under the car park be the king's?”. The Guardian. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Richard III – University of Leicester press statement following permission judgment”. University of Leicester. 16 tháng 8 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 22 tháng 8 năm 2013.

- ^ a b Ashdown-Hill, John (tháng 12 năm 2012). “The Search for Richard III – DNA, documentary evidence and religious knowledge”. Ricardian Bulletin. Richard III Society: 31–32.

- ^ a b “Family tree: Cecily Neville (1415–1495) Duchess of York”. University of Leicester. Truy cập ngày 4 tháng 2 năm 2013.

- ^ “Richard III dig: 'It does look like him'”. BBC News. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Ibsen's mtDNA sequence: 16069T, 16126C, 73G, 146C, 185A, 188G, 263G, 295T, 315.1C in Ashdown-Hill, John (2013), p. 161.

- ^ “Detailed Genealogical Information” (PDF). University of Leicester. Truy cập ngày 26 tháng 10 năm 2021.

- ^ “Living Relatives”. The Discovery of Richard III. University of Leicester. Truy cập ngày 26 tháng 3 năm 2015.

- ^ “Lines of descent”. The Discovery of Richard III. University of Leicester. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 3 năm 2015.

- ^ a b Rowley, Tom (23 tháng 3 năm 2015). “Richard III burial: Five centuries on, the last medieval king finally gets honour in death”. Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. tr. 3. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 3 năm 2015.

- ^ Boswell, Randy (27 tháng 8 năm 2012). “Canadian family holds genetic key to Richard III puzzle”. Postmedia News. Bản gốc lưu trữ 31 Tháng tám năm 2012. Truy cập 30 Tháng tám năm 2012.

- ^ a b “Results of the DNA analysis”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Geneticist Dr. Turi King and genealogist Professor Kevin Schürer give key evidence on the DNA testing”. University of Leicester. Truy cập ngày 5 tháng 2 năm 2013.

- ^ Burns, John F. (4 tháng 2 năm 2013). “Bones under parking lot belonged to Richard III”. The New York Times. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 2 năm 2013.

- ^ Ehrenberg, Rachel (6 tháng 2 năm 2013). “A king's final hours, told by his mortal remains”. Science News. Society for Science & the Public. Truy cập ngày 8 tháng 2 năm 2013.

- ^ Bower, Dick (Director) (27 tháng 2 năm 2013). Richard III: The Unseen Story (Television documentary). Darlow Smithson Productions.

- ^ Hicks, M. (2017). “The Family of Richard III”. Amberley: 55–56, 187–190.

- ^ Mason, Emma (23 tháng 3 năm 2015). “Was the skeleton in the Leicester car park really Richard III?”. BBC History Magazine.

- ^ “Injuries to the skull 1 – 2”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Injuries to the skull 3 – 6”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013.

- ^ a b “Injuries to the skull 7 – 8”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Nick (17 tháng 9 năm 2014). “King Richard III was probably hacked and stabbed to death in battle, according to a new study”. Washington Post. Truy cập ngày 18 tháng 9 năm 2014.

- ^ a b Appleby, J; và đồng nghiệp (17 tháng 9 năm 2014). “Perimortem trauma in King Richard III: a skeletal analysis”. The Lancet. Elsevier. 385 (9964): 253–259. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60804-7. hdl:2381/33280. PMID 25238931. S2CID 13248948.

- ^ a b “Injuries to the body 9 – 10”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ a b c d “What the bones can and can't tell us”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Graphic: Richard III's injuries and how he died”. The Telegraph. 5 tháng 2 năm 2013. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 5 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 7 tháng 9 năm 2013.

- ^ a b “Armouries finds King in the Car Park”. Royal Armouries. Bản gốc lưu trữ 26 Tháng hai năm 2015. Truy cập 27 Tháng Một năm 2015.

- ^ a b “Richard III wounds match medieval Welsh poem description”. BBC News. 15 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Skidmore, Chris (2014). Bosworth: The Birth of the Tudors. Phoenix. tr. 309. ISBN 978-0-7538-2894-6.

- ^ “Spine”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Radiocarbon dating and analysis”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Quenqua, Douglas (25 tháng 8 năm 2014). “Richard III's rich diet of fish and exotic birds”. The New York Times. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 9 năm 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Pitts, Mike (March–April 2015). “The reburial of Richard III”. British Archaeology (141). tr. 26–33.

- ^ a b “University of Leicester announces discovery of King Richard III”. University of Leicester. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “The search for Richard III – completed”. University of Leicester. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “Richard III dig: DNA confirms bones are king's”. BBC. 4 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Cullinane, Susannah (5 tháng 2 năm 2013). “Richard III: Is this the face that launched 1,000 myths?”. CNN.com. Truy cập ngày 7 tháng 2 năm 2013.

- ^ “Genomes of Richard III and his proven relative to be sequenced”. University of Leicester. 11 tháng 2 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 3 năm 2014.

- ^ King, Gonzalez Fortes, Balaresque et al (2014)

- ^ “Richard III: The King in the Car Park”. Channel 4. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ a b “Following hit doc, More4 to screen Richard III: The Unseen Story”. Channel 4 News. 13 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ “'King in the Car Park' documentary wins top television award”. University of Leicester. 20 tháng 3 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Pitts, Mike (November–December 2013). “Richard III update: a coffin, walls and reburial”. British Archaeology (133). tr. 6–7.

- ^ “New twist in mystery of lead coffin found near Richard III's grave”. Leicester Mercury. 17 tháng 10 năm 2013. Bản gốc lưu trữ 21 Tháng hai năm 2015. Truy cập 23 Tháng hai năm 2015.

- ^ Carson, Ashdown-Hill, Johnson, Johnson & Langley, p. 85.

- ^ “Richard III set to be buried in Leicester as university makes final decision”. Leicester Mercury. 7 tháng 2 năm 2013. Bản gốc lưu trữ 25 Tháng mười hai năm 2014. Truy cập 11 Tháng hai năm 2013.

- ^ “Richard III: New battle looms over final resting place”. CNN. 6 tháng 2 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 6 năm 2013.

- ^ a b Britten, Nick; Hough, Andrew (4 tháng 2 năm 2013). “Richard III to be re-interred in major ceremony at Leicester Cathedral”. The Daily Telegraph. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 7 tháng 2 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 12 năm 2002.

- ^ Pollard, AJ (2004). “Edward [Edward of Middleham], prince of Wales (1474x6–1484)”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography . Oxford University Press (xuất bản tháng 9 năm 2010). doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/38659. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 8 năm 2013. (yêu cầu Đăng ký hoặc có quyền thành viên của thư viện công cộng Anh.)

- ^ a b Brown, John Murray (3 tháng 2 năm 2013). “Tug-of-war brews over 'king in car park'”. Financial Times. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ a b “King Richard III burial row heads to High Court”. BBC News. 1 tháng 5 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ a b “Richard III: King's reburial row goes to judicial review”. BBC News. 16 tháng 8 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 19 tháng 8 năm 2013.

- ^ “Richard III remains: Reinterment delay 'disrespectful'”. BBC News. 16 tháng 7 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 27 tháng 7 năm 2013.

- ^ Ormrod, Mark (5 tháng 2 năm 2013). “A burial fit for a King”. University of York. Truy cập ngày 7 tháng 5 năm 2013.

- ^ “Richard III: More or Less examines how many descendents he could have”. BBC News. 19 tháng 8 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 8 năm 2013.

- ^ “Richard III remains: Judicial review hearing starts”. BBC News. 13 tháng 3 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 5 năm 2014.

- ^ “Richard III: Judicial review bones decision deferred”. BBC News. 14 tháng 3 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 3 năm 2014.

- ^ “Richard III reburial court bid fails”. BBC News. 23 tháng 5 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 5 năm 2014.

- ^ “Cathedral announces first step in interment process”. Leicester.anglican.org. 12 tháng 2 năm 2013. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 14 tháng 4 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 8 tháng 8 năm 2013.

- ^ “Brief for Architects: Grave for King Richard III” (PDF). Leicester Cathedral. Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ 30 tháng Năm năm 2013. Truy cập 7 tháng Năm năm 2013.

- ^ “Response to the Architects' Brief produced by Leicester Cathedral for King Richard III's reburial: press release”. Richard III Society. 4 tháng 5 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 6 năm 2013.

- ^ Stone, Phil (tháng 7 năm 2013). “From Darkness into Light”. Military History Monthly. London: Current Publishing. 34: 10.

- ^ “Richard III tomb design unveiled in Leicester”. BBC News. 16 tháng 6 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 17 tháng 1 năm 2015.; Kennedy, Maev (16 tháng 6 năm 2014). “Richard III's bones will be reburied in a coffin made by his descendant”. The Guardian. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 11 năm 2019.

- ^ “Leicester's Richard III statue reinstated at Cathedral Gardens”. BBC News. 26 tháng 6 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 17 tháng 1 năm 2015.

- ^ “Richard III's remains sealed inside coffin at Leicester University – BBC News”. Bbc.co.uk. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 3 năm 2015.

- ^ “Reburial TImetable Archives – King Richard III in Leicester”. Kingrichardinleicester.com. 16 tháng 2 năm 2015. Bản gốc lưu trữ 24 Tháng Ba năm 2015. Truy cập 25 Tháng Ba năm 2015.

- ^ Channel 4 television program Richard III, The Return of the King, 5.10 pm to 8 pm, Sunday 22 March 2015 in Britain.

- ^ Anon (23 tháng 3 năm 2015). “Richard III: More than 5,000 people visit Leicester Cathedral coffin”. BBC News. BBC. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 3 năm 2015.

- ^ “About the Series”. PBS. 11 tháng 12 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 5 năm 2018.

- ^ “Benedict Cumberbatch to read poem at Richard III's reburial”. CNN. 25 tháng 3 năm 2015. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 3 năm 2015.

- ^ “Richard III: The Reburial”. Channel Four. 23 tháng 3 năm 2015. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 3 năm 2015.

- ^ “Order of Service for the Reinterment of the Remains of King Richard III” (PDF). 26 tháng 3 năm 2015. Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 26 tháng 3 năm 2015. Truy cập ngày 26 tháng 3 năm 2015.

- ^ “Public to attend Richard III reburial at Leicester Cathedral”. BBC News. 5 tháng 12 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ a b Watson, Grieg (22 tháng 7 năm 2014). “Does Leicester's Richard III centre live up to the hype?”. BBC News. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Warzynski, Peter (3 tháng 12 năm 2012). “Leicester City Council buys the site of its Richard III centre for £850,000”. Leicester Mercury. Bản gốc lưu trữ 2 Tháng sáu năm 2013. Truy cập 23 Tháng hai năm 2015.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (22 tháng 7 năm 2013). “Richard III visitor centre in Leicester opens its doors to the public”. The Guardian. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Landrø, Juliet; Zahl, Hilde (5 tháng 2 năm 2013). “Ønsker å grave opp de norske "asfaltkongene"”. NRK (bằng tiếng Na Uy). Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Watson, Grieg (12 tháng 2 năm 2013). “Richard III: Greatest archaeological discovery of all?”. BBC News. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 3 năm 2015.

- ^ “Richard III and Raneiri inspire Leicester City to English Premiership title”. Herald Scotland (bằng tiếng Anh). Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 3 năm 2017.

- ^ Michael Morpurgo (2016). “The Fox and the Ghost King”. michaelmorpurgo.com. HarperCollins.

- ^ Vlessing, Etan (10 tháng 8 năm 2022). “IFC Films Nabs Stephen Frears' 'The Lost King'”. The Hollywood Reporter (bằng tiếng Anh). Truy cập ngày 17 tháng 8 năm 2022.

Bibliography[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- Ashdown-Hill, John (2013). The Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA. Stroud, England: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-9205-6.

- Ashdown-Hill, John; David Johnson; Wendy Johnson; Pippa Langley (2014). Carson, Annette (biên tập). Finding Richard III: The Official Account of Research by the Retrieval & Reburial Project. Horstead: Imprimis Imprimatur. ISBN 978-0-9576840-2-7.

- Baldwin, David (1986). “King Richard's Grave in Leicester” (PDF). Transactions. Leicester Archaeological and Historical Society. 60.

- Bennett, Michael John (1985). The Battle of Bosworth. Gloucester: Alan Sutton. ISBN 978-0-8629-9053-4.

- Buckley, Richard; Mathew Morris; Jo Appleby; Turi King; Deirdre O'Sullivan; Lin Foxhall (2013). “"The King in the Car Park": New Light on the Death and Burial of Richard III in the Grey Friars Church, Leicester, in 1485”. Antiquity. 87 (336): 519–538. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00049103.

- Halsted, Caroline Amelia (1844). Richard III, as Duke of Gloucester and King of England. Volume 2. Carey and Hart. OCLC 2606580.

- The Grey Friars Research Team; Kennedy, Maev; Foxhall, Lin (2015). The Bones of a King: Richard III Rediscovered. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1118783146.

- Hipshon, David (2009). Richard III and the Death of Chivalry. History Press. ISBN 978-0750950749.

- King, TE; Gonzalez Fortes, G; Balaresque, P; Thomas, MG; Balding, D; Maisano Delser, P; Neumann, Rita; Parson, Walther; Knapp, Michael; Walsh, Susan; Tonasso, Laure; Holt, John; Kayser, Manfred; Appleby, Jo; Forster, Peter; Ekserdjian, David; Hofreiter, Michael; Schürer, Kevin (2014). “Identification of the remains of King Richard III”. Nature Communications. 5 (5631): 5631. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.5631K. doi:10.1038/ncomms6631. PMC 4268703. PMID 25463651.

- Langley, Philippa; Jones, Michael (2014). The Search for Richard III: The King's Grave. John Murray. ISBN 978-1-84854-893-0.

- Mathew, Morris; Richard Buckley (2013). Richard III: The King Under the Car Park. Leicester: University of Leicester Archaeological Services. ISBN 978-0-9574792-2-7.

- Penn, Thomas (2011). Winter King – Henry VII and the Dawn of Tudor England. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-9156-9.

- Pitts, Mike (2014). Digging for Richard III: How Archaeology Found the King. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-25200-0.

- Rees, EA (2008). A Life of Guto'r Glyn. Tal-y-bont, Ceredigion: Y Lolfa. ISBN 978-0-86243-971-2.

- Rhodes, Neil (1997). English Renaissance Prose: History, Language, and Politics. Tempe, AZ: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies. ISBN 978-0-8669-8205-4.

Further reading[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- Schwyzer, Philip (2013). Shakespeare and the Remains of Richard III. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199676101.

External links[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

| Wikimedia Commons có thêm hình ảnh và phương tiện truyền tải về GDAE/Khai quật và cải táng vua Richard III của Anh. |

- University of Leicester Richard III website (University of Leicester)

- Videos and links about the discovery of Richard III's body (University of Leicester)

- About the facial reconstruction (University of Dundee)

- Timetable of reburial week events 22–28 March 2015