Khác biệt giữa bản sửa đổi của “Quark”

Không có tóm lược sửa đổi |

Không có tóm lược sửa đổi |

||

| Dòng 52: | Dòng 52: | ||

}}</ref> Với lý do này, rất nhiều điều về các quark được biết đến đã được dẫn ra từ các hadron chúng tổ hợp lên. |

}}</ref> Với lý do này, rất nhiều điều về các quark được biết đến đã được dẫn ra từ các hadron chúng tổ hợp lên. |

||

Có 6 loại quark, còn được biết đến là ''[[ |

Có 6 loại quark, còn được biết đến là ''[[hương (vật lý hạt))|hương]]'': [[Quark trên|trên]] (u), [[Quark dưới|dưới]] (d), [[Quark duyên|duyên]] (c), [[Quark lạ|lạ]] (s), [[Quark đỉnh|đỉnh]] (t), và [[Quark đáy|đáy]] (b).<ref name="HyperphysicsQuark"> |

||

{{cite web |

{{cite web |

||

|author=R. Nave |

|author=R. Nave |

||

| Dòng 93: | Dòng 93: | ||

}}</ref> Cả 6 quark đều đã được quan sát trong các máy gia tốc thực nghiệm; quark cuối cùng được khám phá là quark đỉnh t được quan sát tại [[Fermilab]] năm 1995.<ref name="Carithers"/> |

}}</ref> Cả 6 quark đều đã được quan sát trong các máy gia tốc thực nghiệm; quark cuối cùng được khám phá là quark đỉnh t được quan sát tại [[Fermilab]] năm 1995.<ref name="Carithers"/> |

||

== Phân loại == |

|||

Xem thêm: [[Mô hình chuẩn]] |

|||

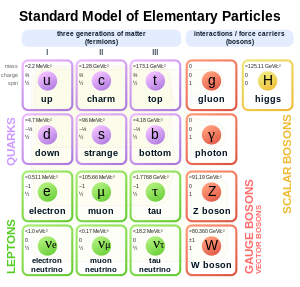

[[Image:Standard Model of Elementary Particles.svg|thumb|300px|Six of the particles in the [[Standard Model]] are quarks (shown in purple). Each of the first three columns forms a ''[[generation (particle physics)|generation]]'' of matter.|alt=A four-by-four table of particles. Columns are three generations of matter (fermions) and one of forces (bosons). In the first three columns, two rows contain quarks and two leptons. The top two rows' columns contain up (u) and down (d) quarks, charm (c) and strange (s) quarks, top (t) and bottom (b) quarks, and photon (γ) and gluon (g), respectively. The bottom two rows' columns contain electron neutrino (ν sub e) and electron (e), muon neutrino (ν sub μ) and muon (μ), and tau neutrino (ν sub τ) and tau (τ), and Z sup 0 and W sup ± weak force. Mass, charge, and spin are listed for each particle.]] |

|||

The [[Standard Model]] is the theoretical framework describing all the currently known [[elementary particle]]s, as well as the unobserved<ref group="nb">{{As of|2009|07}}.</ref> [[Higgs boson]].<ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|author=C. Amsler ''et al.'' ([[Particle Data Group]]) |

|||

|title= Higgs Bosons: Theory and Searches |

|||

|url=http://pdg.lbl.gov/2009/reviews/rpp2009-rev-higgs-boson.pdf |

|||

|journal=[[Physics Letters B]] |

|||

|volume=667 |issue=1 |pages=1–1340 |

|||

|year=2008 |

|||

|doi=10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018 |

|||

}}</ref> This model contains six [[flavour (particle physics)|flavor]]s of quarks ({{SubatomicParticle|quark}}), named [[up quark|up]] ({{SubatomicParticle|up quark}}), [[down quark|down]] ({{SubatomicParticle|down quark}}), [[charm quark|charm]] ({{SubatomicParticle|charm quark}}), [[strange quark|strange]] ({{SubatomicParticle|strange quark}}), [[top quark|top]] ({{SubatomicParticle|top quark}}), and [[bottom quark|bottom]] ({{SubatomicParticle|bottom quark}}).<ref name="HyperphysicsQuark"/> [[Antiparticle]]s of quarks are called ''antiquarks'', and are denoted by a bar over the symbol for the corresponding quark, such as {{SubatomicParticle|Up antiquark}} for an up antiquark. As with [[antimatter]] in general, antiquarks have the same mass, [[mean lifetime]], and spin as their respective quarks, but the electric charge and other [[charge (physics)|charges]] have the opposite sign.<ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|author=S.S.M. Wong |

|||

|title=Introductory Nuclear Physics |

|||

|edition=2nd |

|||

|page=30 |

|||

|publisher=[[Wiley Interscience]] |

|||

|year=1998 |

|||

|isbn=0-471-23973-9 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Quarks are [[spin-½|spin-{{frac|1|2}}]] particles, implying that they are [[fermion]]s according to the [[spin-statistics theorem]]. They are subject to the [[Pauli exclusion principle]], which states that no two identical fermions can simultaneously occupy the same [[quantum state]]. This is in contrast to [[boson]]s (particles with integer spin), of which any number can be in the same state.<ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|author=K.A. Peacock |

|||

|title=The Quantum Revolution |

|||

|page=125 |

|||

|publisher=[[Greenwood Publishing Group]] |

|||

|year=2008 |

|||

|isbn=031333448X |

|||

}}</ref> Unlike [[lepton]]s, quarks possess [[color charge]], which causes them to engage in the [[strong interaction]]. The resulting attraction between different quarks causes the formation of composite particles known as ''[[hadron]]s'' (see "[[#Strong interaction and color charge|Strong interaction and color charge]]" below). |

|||

The quarks which determine the [[quantum number]]s of hadrons are called ''valence quarks''; apart from these, any hadron may contain an indefinite number of [[virtual particle|virtual]] (or ''[[#Sea quarks|sea]]'') quarks, antiquarks, and [[gluon]]s which do not influence its quantum numbers.<ref> |

|||

{{Đang dịch 2 (nguồn)|ngày=30 |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|tháng=04 |

|||

|author=B. Povh, C. Scholz, K. Rith, F. Zetsche |

|||

|năm=2010 |

|||

|title=Particles and Nuclei |

|||

|1 = tiếng Anh |

|||

|page=98 |

|||

}} |

|||

|publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |

|||

|year=2008 |

|||

|isbn=3540793674 |

|||

}}</ref> There are two families of hadrons: [[baryon]]s, with three valence quarks, and [[meson]]s, with a valence quark and an antiquark.<ref>Section 6.1. in |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|author=P.C.W. Davies |

|||

|title=The Forces of Nature |

|||

|publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |

|||

|year=1979 |

|||

|isbn=052122523X |

|||

}}</ref> The most common baryons are the proton and the neutron, the building blocks of the [[atomic nucleus]].<ref name="Knowing"> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|author=M. Munowitz |

|||

|title=Knowing |

|||

|page=35 |

|||

|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |

|||

|year=2005 |

|||

|isbn=0195167376 |

|||

}}</ref> A great number of hadrons are known (see [[list of baryons]] and [[list of mesons]]), most of them differentiated by their quark content and the properties these constituent quarks confer. The existence of [[exotic hadron|"exotic" hadrons]] with more valence quarks, such as [[tetraquark]]s ({{SubatomicParticle|quark}}{{SubatomicParticle|quark}}{{SubatomicParticle|antiquark}}{{SubatomicParticle|antiquark}}) and [[pentaquark]]s ({{SubatomicParticle|quark}}{{SubatomicParticle|quark}}{{SubatomicParticle|quark}}{{SubatomicParticle|quark}}{{SubatomicParticle|antiquark}}), has been conjectured<ref name="PDGTetraquarks"> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|author=W.-M. Yao ''et al.'' ([[Particle Data Group]]) |

|||

|title=Review of Particle Physics: Pentaquark Update |

|||

|url=http://pdg.lbl.gov/2006/reviews/theta_b152.pdf |

|||

|journal=[[Journal of Physics G]] |

|||

|volume=33 |issue=1 |pages=1–1232 |

|||

|year=2006 |

|||

|doi=10.1088/0954-3899/33/1/001 |

|||

}}</ref> but not proven.<ref group="nb">Several research groups claimed to have proven the existence of tetraquarks and pentaquarks in the early 2000s. While the status of tetraquarks is still under debate, all known pentaquark candidates have since been established as non-existent.</ref><ref name="PDGTetraquarks"/><ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|author=C. Amsler ''et al.'' ([[Particle Data Group]]) |

|||

|title=Review of Particle Physics: Pentaquarks |

|||

|url=http://pdg.lbl.gov/2008/reviews/pentaquarks_b801.pdf |

|||

|journal=[[Physics Letters B]] |

|||

|volume=667 |issue=1 |pages=1–1340 |

|||

|year=2008 |

|||

|doi=10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018 |

|||

}} <br />{{cite journal |

|||

|author=C. Amsler ''et al.'' ([[Particle Data Group]]) |

|||

|title=Review of Particle Physics: New Charmonium-Like States |

|||

|url=http://pdg.lbl.gov/2008/reviews/rpp2008-rev-new-charmonium-like-states.pdf |

|||

|journal=[[Physics Letters B]] |

|||

|volume=667 |issue=1 |pages=1–1340 |

|||

|year=2008 |

|||

|doi=10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018 |

|||

}} <br />{{cite book |

|||

|author=E.V. Shuryak |

|||

|title=The QCD Vacuum, Hadrons and Superdense Matter |

|||

|page=59 |

|||

|publisher=[[World Scientific]] |

|||

|year=2004 |

|||

|isbn=9812385746 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Elementary fermions are grouped into three [[generation (particle physics)|generation]]s, each comprising two leptons and two quarks. The first generation includes up and down quarks, the second charm and strange quarks, and the third top and bottom quarks. All searches for a fourth generation of quarks and other elementary fermions have failed,<ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|author=C. Amsler ''et al.'' ([[Particle Data Group]]) |

|||

|title=Review of Particle Physics: b′ (4th Generation) Quarks, Searches for |

|||

|url=http://pdg.lbl.gov/2008/listings/q008.pdf |

|||

|journal=[[Physics Letters B]] |

|||

|volume=667 |issue=1 |pages=1–1340 |

|||

|year=2008 |

|||

|doi=10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018 |

|||

}} <br /> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|author=C. Amsler ''et al.'' ([[Particle Data Group]]) |

|||

|title=Review of Particle Physics: t′ (4th Generation) Quarks, Searches for |

|||

|url=http://pdg.lbl.gov/2008/listings/q009.pdf |

|||

|journal=[[Physics Letters B]] |

|||

|volume=667 |issue=1 |pages=1–1340 |

|||

|year=2008 |

|||

|doi=10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018 |

|||

}}</ref> and there is strong indirect evidence that no more than three generations exist.<ref group="nb">The main evidence is based on the [[resonance width]] of the [[W and Z bosons|{{SubatomicParticle|Z boson0}} boson]], which constrains the 4th generation neutrino to have a mass greater than ~{{val|45|u=GeV/c2}}. This would be highly contrasting with the other three generations' neutrinos, whose masses cannot exceed {{val|2|u=MeV/c2}}.</ref><ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|author=D. Decamp |

|||

|title=Determination of the number of light neutrino species |

|||

|journal=[[Physics Letters B]] |

|||

|volume=231 |issue=4 |pages=519 |

|||

|year=1989 |

|||

|doi=10.1016/0370-2693(89)90704-1 |

|||

}} <br /> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|author=A. Fisher |

|||

|title=Searching for the Beginning of Time: Cosmic Connection |

|||

|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=eyPfgGGTfGgC&pg=PA70&dq=quarks+no+more+than+three+generations&lr=&as_brr=3&ei=BZjvSeDyKo7skwTFrPnvAw |

|||

|journal=[[Popular Science]] |

|||

|volume=238 |issue=4 |page=70 |

|||

|year=1991 |

|||

|doi= |

|||

}} <br /> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|author=J.D. Barrow |

|||

|title=The Origin of the Universe |

|||

|chapter=The Singularity and Other Problems |

|||

|pages= |

|||

|origyear=1994 |

|||

|edition=Reprint |

|||

|year=1997 |

|||

|publisher=[[Basic Books]] |

|||

|isbn=978-0465053148 |

|||

}}</ref> Particles in higher generations generally have greater mass and lesser stability, causing them to [[particle decay|decay]] into lower-generation particles by means of [[weak interaction]]s. Only first-generation (up and down) quarks occur commonly in nature. Heavier quarks can only be created in high-energy collisions (such as in those involving [[cosmic ray]]s), and decay quickly; however, they are thought to have been present during the first fractions of a second after the [[Big Bang]], when the universe was in an extremely hot and dense phase (the [[quark epoch]]). Studies of heavier quarks are conducted in artificially created conditions, such as in [[particle accelerators]].<ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|author=D.H. Perkins |

|||

|title=Particle Astrophysics |

|||

|page=4 |

|||

|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |

|||

|year=2003 |

|||

|isbn=0198509529 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Having electric charge, mass, color charge, and flavor, quarks are the only known elementary particles that engage in all four [[fundamental interaction]]s of contemporary physics: electromagnetism, gravitation, strong interaction, and weak interaction.<ref name="Knowing" /> Gravitation, however, is usually irrelevant at subatomic scales, and is not described by the Standard Model. |

|||

See the [[#Table of properties|table of properties below]] for a more complete overview of the six quark flavors' properties. |

|||

== Các quark tự do == |

|||

<gallery></gallery> |

|||

== Cấu trúc quark của các hạt cơ bản == |

== Cấu trúc quark của các hạt cơ bản == |

||

| Dòng 221: | Dòng 361: | ||

[[ur:کوارک]] |

[[ur:کوارک]] |

||

[[zh:夸克]] |

[[zh:夸克]] |

||

{{Đang dịch 2 (nguồn)|ngày=30 |

|||

|tháng=04 |

|||

|năm=2010 |

|||

|1 = tiếng Anh |

|||

}} |

|||

Phiên bản lúc 05:51, ngày 30 tháng 4 năm 2010

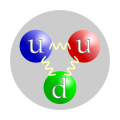

Proton, tổ hợp của 2 quark trên và 1 quark dưới | |

| Cấu trúc | Hạt cơ bản |

|---|---|

| Loại hạt | Fermion |

| Thế hệ | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| Tương tác cơ bản | Điện từ, Hấp dẫn, Mạnh, Yếu |

| Phản hạt | Phản quark |

| Lý thuyết | Murray Gell-Mann (1964) George Zweig (1964) |

| Thực nghiệm | SLAC (~1968) |

| Ký hiệu | q |

| Số loại | 6 (trên, dưới, duyên, lạ, đỉnh, và đáy) |

| Điện tích | +2⁄3 e, −1⁄3 e |

| Màu tích | Có |

| Spin | 1⁄2 |

Quark (phát âm /ˈkwɔrk/ hay /ˈkwɑrk/) là một hạt cơ bản và là một thành phần cơ bản của vật chất. Các quark kết hợp với nhau tạo lên các hạt tổ hợp còn gọi là các hadron, với những hạt ổn định nhất là proton và neutron, những hạt thành phần của hạt nhân nguyên tử.[1] Do một hiệu ứng gọi là sự giam hãm màu, các quark không bao giờ tìm thấy đứng riêng rẽ; chúng chỉ có thể tìm thấy bên trong các hadron..[2][3] Với lý do này, rất nhiều điều về các quark được biết đến đã được dẫn ra từ các hadron chúng tổ hợp lên.

Có 6 loại quark, còn được biết đến là hương: trên (u), dưới (d), duyên (c), lạ (s), đỉnh (t), và đáy (b).[4] Các quark trên (u) và quark dưới (d) có khối lượng nhỏ nhất trong các quark. Các quark nặng hơn nhanh chóng biến đổi sang các quark u và d thông qua một quá trình phân rã hạt: sự biến đổi từ một trạng thái khối lượng cao hơn sang trạng thái khối lượng thấp hơn. Vì điều này, các quark u và d nói chung là ổn định và thường gặp nhất trong vũ trụ, trong khi các quark duyên (c), lạ (s), đỉnh (t), và đáy (b) chỉ có thể được tạo ra trong va chạm năng lượng cao (như trong các tia vũ trụ và trong các máy gia tốc hạt).

Các quark có rất nhiều tính chất nội tại, bao gồm điện tích, tích màu (color charge), spin, và khối lượng. Các quark là những hạt cơ bản duy nhất trong mô hình chuẩn của vật lý hạt đều tham gia vào bốn tương tác cơ bản, hay còn được biết đến là "các lực cơ bản" (tương tác điện từ, tương tác hấp dẫn, tương tác mạnh, và tương tác yếu), cũng như là các hạt cơ bản có điện tích không phải là một số nguyên lần của điện tích nguyên tố. Đối với mỗi vị quark có tương ứng với một loại phản hạt, gọi là phản quark, mà chỉ khác với các quark ở một số tính chất có độ lớn bằng nhau nhưng ngược dấu.

Mô hình quark đã được độc lập đề xuất bởi các nhà vật lý Murray Gell-Mann và George Zweig năm 1964.[5] Các quark được đưa ra như là một phần trong biểu đồ sắp xếp cho các hadron, và có rất ít chứng cứ về sự tồn tại của chúng cho đến tận năm 1968..[6][7] Cả 6 quark đều đã được quan sát trong các máy gia tốc thực nghiệm; quark cuối cùng được khám phá là quark đỉnh t được quan sát tại Fermilab năm 1995.[5]

Phân loại

Xem thêm: Mô hình chuẩn

The Standard Model is the theoretical framework describing all the currently known elementary particles, as well as the unobserved[nb 1] Higgs boson.[8] This model contains six flavors of quarks (q), named up (u), down (d), charm (c), strange (s), top (t), and bottom (b).[4] Antiparticles of quarks are called antiquarks, and are denoted by a bar over the symbol for the corresponding quark, such as u for an up antiquark. As with antimatter in general, antiquarks have the same mass, mean lifetime, and spin as their respective quarks, but the electric charge and other charges have the opposite sign.[9]

Quarks are spin-1⁄2 particles, implying that they are fermions according to the spin-statistics theorem. They are subject to the Pauli exclusion principle, which states that no two identical fermions can simultaneously occupy the same quantum state. This is in contrast to bosons (particles with integer spin), of which any number can be in the same state.[10] Unlike leptons, quarks possess color charge, which causes them to engage in the strong interaction. The resulting attraction between different quarks causes the formation of composite particles known as hadrons (see "Strong interaction and color charge" below).

The quarks which determine the quantum numbers of hadrons are called valence quarks; apart from these, any hadron may contain an indefinite number of virtual (or sea) quarks, antiquarks, and gluons which do not influence its quantum numbers.[11] There are two families of hadrons: baryons, with three valence quarks, and mesons, with a valence quark and an antiquark.[12] The most common baryons are the proton and the neutron, the building blocks of the atomic nucleus.[13] A great number of hadrons are known (see list of baryons and list of mesons), most of them differentiated by their quark content and the properties these constituent quarks confer. The existence of "exotic" hadrons with more valence quarks, such as tetraquarks (qqqq) and pentaquarks (qqqqq), has been conjectured[14] but not proven.[nb 2][14][15]

Elementary fermions are grouped into three generations, each comprising two leptons and two quarks. The first generation includes up and down quarks, the second charm and strange quarks, and the third top and bottom quarks. All searches for a fourth generation of quarks and other elementary fermions have failed,[16] and there is strong indirect evidence that no more than three generations exist.[nb 3][17] Particles in higher generations generally have greater mass and lesser stability, causing them to decay into lower-generation particles by means of weak interactions. Only first-generation (up and down) quarks occur commonly in nature. Heavier quarks can only be created in high-energy collisions (such as in those involving cosmic rays), and decay quickly; however, they are thought to have been present during the first fractions of a second after the Big Bang, when the universe was in an extremely hot and dense phase (the quark epoch). Studies of heavier quarks are conducted in artificially created conditions, such as in particle accelerators.[18]

Having electric charge, mass, color charge, and flavor, quarks are the only known elementary particles that engage in all four fundamental interactions of contemporary physics: electromagnetism, gravitation, strong interaction, and weak interaction.[13] Gravitation, however, is usually irrelevant at subatomic scales, and is not described by the Standard Model.

See the table of properties below for a more complete overview of the six quark flavors' properties.

Cấu trúc quark của các hạt cơ bản

-

Cấu trúc quark của proton

-

Cấu trúc quark của proton

-

Cấu trúc quark của neutron

-

Cấu trúc quark của phản pion (π+)

-

Cấu trúc quark của proton

-

Cấu trúc quark của neutron

-

Cấu trúc quark của phản pion

-

Hai định dạng của các hạt Two possible Spin-combinations for a Nukleon.

Chế ngự và các tính chất của quark

Hương

Spin

Màu

Khối lượng của các quark

Khối lượng quark phổ thông

Khối lượng quark hóa trị

Khối lượng quark nặng

Phản quark

Hạ cấu trúc

Lịch sử

Tham khảo

- ^ “Quark (subatomic particle)”. Encyclopedia Britannica. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 6 năm 2008.

- ^ R. Nave. “Confinement of Quarks”. HyperPhysics. Georgia State University, Department of Physics and Astronomy. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 6 năm 2008.

- ^ R. Nave. “Bag Model of Quark Confinement”. HyperPhysics. Georgia State University, Department of Physics and Astronomy. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 6 năm 2008.

- ^ a b R. Nave. “Quarks”. HyperPhysics. Georgia State University, Department of Physics and Astronomy. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 6 năm 2008.

- ^ a b B. Carithers, P. Grannis (1995). “Discovery of the Top Quark” (PDF). Beam Line. SLAC. 25 (3): 4–16. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 9 năm 2008.

- ^ E.D. Bloom (1969). “High-Energy Inelastic e–p Scattering at 6° and 10°”. Physical Review Letters. 23 (16): 930–934. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.23.930.

- ^ M. Breidenbach (1969). “Observed Behavior of Highly Inelastic Electron–Proton Scattering”. Physical Review Letters. 23 (16): 935–939. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.23.935.

- ^ C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). “Higgs Bosons: Theory and Searches” (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667 (1): 1–1340. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

- ^ S.S.M. Wong (1998). Introductory Nuclear Physics (ấn bản 2). Wiley Interscience. tr. 30. ISBN 0-471-23973-9.

- ^ K.A. Peacock (2008). The Quantum Revolution. Greenwood Publishing Group. tr. 125. ISBN 031333448X.

- ^ B. Povh, C. Scholz, K. Rith, F. Zetsche (2008). Particles and Nuclei. Springer. tr. 98. ISBN 3540793674.Quản lý CS1: nhiều tên: danh sách tác giả (liên kết)

- ^ Section 6.1. in P.C.W. Davies (1979). The Forces of Nature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052122523X.

- ^ a b M. Munowitz (2005). Knowing. Oxford University Press. tr. 35. ISBN 0195167376.

- ^ a b W.-M. Yao et al. (Particle Data Group) (2006). “Review of Particle Physics: Pentaquark Update” (PDF). Journal of Physics G. 33 (1): 1–1232. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/33/1/001.

- ^

C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). “Review of Particle Physics: Pentaquarks” (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667 (1): 1–1340. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). “Review of Particle Physics: New Charmonium-Like States” (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667 (1): 1–1340. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

E.V. Shuryak (2004). The QCD Vacuum, Hadrons and Superdense Matter. World Scientific. tr. 59. ISBN 9812385746. - ^

C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). “Review of Particle Physics: b′ (4th Generation) Quarks, Searches for” (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667 (1): 1–1340. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). “Review of Particle Physics: t′ (4th Generation) Quarks, Searches for” (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667 (1): 1–1340. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. - ^

D. Decamp (1989). “Determination of the number of light neutrino species”. Physics Letters B. 231 (4): 519. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(89)90704-1.

A. Fisher (1991). “Searching for the Beginning of Time: Cosmic Connection”. Popular Science. 238 (4): 70.

J.D. Barrow (1997) [1994]. “The Singularity and Other Problems”. The Origin of the Universe . Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465053148. - ^ D.H. Perkins (2003). Particle Astrophysics. Oxford University Press. tr. 4. ISBN 0198509529.

- ^ Tính đến tháng 7 năm 2009[cập nhật].

- ^ Several research groups claimed to have proven the existence of tetraquarks and pentaquarks in the early 2000s. While the status of tetraquarks is still under debate, all known pentaquark candidates have since been established as non-existent.

- ^ The main evidence is based on the resonance width of the Z⁰

boson, which constrains the 4th generation neutrino to have a mass greater than ~45 GeV/c2. This would be highly contrasting with the other three generations' neutrinos, whose masses cannot exceed 2 MeV/c2.

Xem thêm

Liên kết ngoài

| Wikimedia Commons có thêm hình ảnh và phương tiện truyền tải về Quark. |

- Thí nghiệm vật lý "kỳ lạ" khám phá cấu trúc của proton

- Nobel Vật lý 2004 dành cho thuyết tương tác mạnh

Bài viết này là công việc biên dịch đang được tiến hành từ bài viết tiếng Anh từ một ngôn ngữ khác sang tiếng Việt. Bạn có thể giúp Wikipedia bằng cách hỗ trợ dịch và trau chuốt lối hành văn tiếng Việt theo cẩm nang của Wikipedia. |