Thành viên:Guest001/translated colombia article

Colombia (/[invalid input: 'icon'][invalid input: 'en-us-Colombia.ogg']kəˈlʌmbiə/), tên chính thức là Cộng hòa Colombia (tiếng Tây Ban Nha: República de Colombia, phát âm [reˈpuβlika ðe koˈlombja] (![]() nghe)), là một nước cộng hòa lập hiến tại phái đông bắc Nam Mỹ. Colombia giáp về phía đông với Venezuela[1] và Brazil;[2] về phía nam với Ecuador và Peru;[3] về phía bắc với Biển Caribbe; về phái tây bắc với Panama; và về phái tây với Thái bình dương. Colombia cũng chia sẻ đường biên giới trên biển với Venezuela, Jamaica, Haiti, Cộng hòa Dominica, Honduras, Nicaragua và Costa Rica.[4][5] với một dân số hơn 45 triệu người, Colombia có dân số đông thứ 29 trên thế giới và thứ hai tại Nam Mỹ, sau Brazil. Colombia có dân số lớn thứ ba trong các nước nói tiếng tây ban nha trên thế giới, sau Mexico và tây ban nha.

nghe)), là một nước cộng hòa lập hiến tại phái đông bắc Nam Mỹ. Colombia giáp về phía đông với Venezuela[1] và Brazil;[2] về phía nam với Ecuador và Peru;[3] về phía bắc với Biển Caribbe; về phái tây bắc với Panama; và về phái tây với Thái bình dương. Colombia cũng chia sẻ đường biên giới trên biển với Venezuela, Jamaica, Haiti, Cộng hòa Dominica, Honduras, Nicaragua và Costa Rica.[4][5] với một dân số hơn 45 triệu người, Colombia có dân số đông thứ 29 trên thế giới và thứ hai tại Nam Mỹ, sau Brazil. Colombia có dân số lớn thứ ba trong các nước nói tiếng tây ban nha trên thế giới, sau Mexico và tây ban nha.

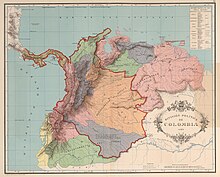

Lãnh thổ mà ngày nay là "Colombia" được cư dân bản địa bao gồm người Muisca, Quimbaya, và Tairona cư trú đầu tiên. Người tây ban nha đến vào năm 1499 bắt đầu thời kỳ xâm lược và thực dân thành lập Phó vương New Granada (Ngày nay bao gồm các nước Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, khu vực phía tây bắc Brazil và Panama) với thủ đô tại Bogotá.[6] Độc lập khỏi Tây ban nha vào năm 1819, but by 1830 "Đại Colombia" đã tan rã vì sự ly khai của Venezuela và Ecuador. Lãnh thổ ngày nay là Colombia và Panama nổi lên là Công hòa Tân Granada. Trước khi cuối cùng Cộng hòa Colombia tuyên bố thành lập năm 1863, Công hòa Tân Granada đã thử nghiệm với chế độ liên bang là Liên bang Granadine (1858), và sau đó là Hợp chúng quốc Colombia (1863).[7] Panama ly khai vào năm 1903 dưới áp lực phải thực hiện những trách nhiệm tài chính đối với chính phủ Mỹ nhằm xây dựng kênh đào Panama.

Colombia có truyền thống về chính thể lập hiến lâu đời. Đảng bảo thủ và đảng tự do, được thành lập lần lượt năm 1848 và 1849, là hai trong số các đảng phái chính trị lâu đời nhất tại châu mỹ. nhưng tình trạng căng thẳng giữa hai đảng phái này thường xuyên nổ ra trở thành bạo lực, đỉnh điểm là trong Chieenas tranh một nghìn ngày (1899–1902) và La Violencia, khởi đầu năm 1948. cho đến những năm 1960, các lực lượng chính phủ gồm phe nổi dậy cánh tả và lực lượng bán quân sự cánh hữu đã đánh nhau trở thành cuộc xung đột vũ trang diễn ra lâu nhất châu Mỹ. Cung cấp bởi việc buôn bán cocaine, đỉnh điểm của cuộc leo thang này là vào những năm 1980. Nhưng, trong thập niêm gần đây (những năm 2000) bạo lực đã giảm bớt đáng kể. Nhiều nhóm bán quân sự được cho giải giáp là một trong những biện pháp hòa bình có thể gây tranh cãi đối với chính phủ, và các nhóm du kích đã mất kiểm soát tại nhiều khu vực mà họ đã từng thống trị.[7] Trong khi tỷ lệ giết người của Colombia, sau nhiều năm là một trong số những tỷ lệ cao nhất trên thế giới, đã giảm một nửa từ năm 2002 đến 2006.[8] năm 2009 và 2010 chứng kiến mộ sự tăng lên trong tỷ lệ giết người tại đô thị, đặc biệt là thành phố Medellín, bị quy cho các băng đảng chiến tranh và những nhóm nối nghiệp bán quân sự.[9][10][11] theo viện nghiên cứu Maplecroft, năm 2010 Colombia có nguy cơ khủng bố cao thứ sáu trên thế giới.[12][13]

Colombia is a standing middle power[14] with the fourth largest economy in Latin America. Sự bất bình đẳng và sự phân phối không đề về sự giàu có là phổ biến.[15] Năm 1990, tỷ số thu nhập giữa 10 % người giàu nhấp và nghèo nhất là 40-to-one. Sau một thập niên của sự suy thoái và cải tổ kinh tế, tỷ số này leo lên đến 80-to-one năm 2000.[16]Năm 2009, Colombia đạt đến hệ số Gini là 0.587, một chỉ số cao nhất Mỹ Latin.[17] Theo văn phòng cao ủy liên hiệp quốc về các quyền con người, "đã có sự giảm bớt trong tỷ lệ nghèo khổ những năm gần đây, nhưng khoảng phân nửa dân số vẫn sống dưới mức nghèo" vào năm 2008-2009.[18] tính toán chính thức cho năm 2009 chỉ ra là khoảng 46% người Colombia sống dưới mức nghèo khổ và 17% sống "nghèo khổ vô cùng".[19][20]

Colombia rất đa dạng về mặt dân tộc, do sự tương tác giữa các con cháu của những dân cư bản địa, những người đi khai hoang người Tây ban nha, các nô lệ châu phi cùng với những người di cư từ Châu Âu trong thế kỷ 20 và Trung đông đã đem lại một di sản văn hóa giàu có. Điều này cũng bị ảnh hưởng bởi địa lý đa dạng của Colombia. Phần lớn các trung tâm đô thị nằm ở những vùng đất cao của dãy Andes, lãnh thổ colombia cũng bao gồm cả rừng rậm nhiệt đới Amazon, đồng cỏ nhiệt đới và cả hai bờ biển both Caribbea và thái bình dương. Về mặt sinh thái, Colombia là một trong số 17 quốc gia megadiverse trên thế giới (đa dạng sinh học nhất cho mỗi đơn vị khu vực).[21]

Etymology[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The word "Colombia" comes from Christopher Columbus (Spanish: Cristóbal Colón). It was conceived by the Venezuelan revolutionary Francisco de Miranda as a reference to all the New World, but especially to those territories and colonies under Spanish and Portuguese rule. The name was later adopted by the Republic of Colombia of 1819, formed out of the territories of the old Viceroyalty of New Granada (modern-day Colombia, Panama, Venezuela and Ecuador).[22]

In 1835, when Venezuela and Ecuador broke away, the Cundinamarca region that remained became a new country — the Republic of New Granada. In 1858 New Granada officially changed its name to the Grenadine Confederation, then in 1863 the United States of Colombia, before finally adopting its present name — the Republic of Colombia — in 1886.[22]

Geography[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Colombia is bordered to the east by Venezuela and Brazil; to the south by Ecuador and Peru; to the north by Panama and the Caribbean Sea; and to the west by Ecuador and the Pacific Ocean. Including its Caribbean islands, it lies between latitudes 14°N and 5°S, and longitudes 66° and 82°W.

Part of the Ring of Fire, a region of the world subject to earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, Colombia is dominated by the Andes mountains. Beyond the Colombian Massif (in the south-western departments of Cauca and Nariño) these are divided into three branches known as cordilleras (mountain ranges): the Cordillera Occidental, running adjacent to the Pacific coast and including the city of Cali; the Cordillera Central, running between the Cauca and Magdalena river valleys (to the west and east respectively) and including the cities of Medellín, Manizales, Pereira and Armenia; and the Cordillera Oriental, extending north east to the Guajira Peninsula and including Bogotá, Bucaramanga and Cúcuta. Peaks in the Cordillera Occidental exceed 13.000 ft (3.962 m), and in the Cordillera Central and Cordillera Oriental they reach 18.000 ft (5.486 m).[23] At 8.500 ft (2.591 m), Bogotá is the highest city of its size in the world.

East of the Andes lies the savanna of the Llanos, part of the Orinoco River basin, and, in the far south east, the jungle of the Amazon rainforest. Together these lowlands comprise over half Colombia's territory, but they contain less than 3% of the population. To the north the Caribbean coast, home to 20% of the population and the location of the major port cities of Barranquilla and Cartagena, generally consists of low-lying plains, but it also contains the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountain range, which includes the country's tallest peaks (Pico Cristóbal Colón and Pico Simón Bolívar), and the Guajira Desert. By contrast the narrow and discontinuous Pacific coastal lowlands, backed by the Serranía de Baudó mountains, are covered in dense vegetation and sparsely populated. The principal Pacific port is Buenaventura.

Colombian territory also includes a number of Caribbean and Pacific islands.

Environmental issues[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The environmental challenges faced by Colombia are caused by both natural and human hazards. Many natural hazards result from Colombia's position along the Pacific Ring of Fire and the consequent geological instability. Colombia has 15 major volcanoes, the eruptions of which have on occasion resulted in substantial loss of life, such as at Armero in 1985, and geological faults that have caused numerous devastating earthquakes, such as the 1999 Armenia earthquake. Heavy floods both in mountainous areas and in low-lying watersheds and coastal regions regularly cause deaths and considerable damage to property during the rainy seasons. Rainfall intensities vary with the El Niño-Southern Oscillation which occurs in unpredictable cycles, at times causing especially severe flooding.

Human induced deforestation has substantially changed the Andean landscape and has started to creep into the rainforests of Amazonia and the Pacific coast. Deforestation is also linked to the conversion of lowland tropical forests to oil palm plantations. However, compared to neighbouring countries rates of deforestation in Colombia are still relatively low.[24] In urban areas, the use of fossil fuels, and other human produced waste have contaminated the local environment. Demand from rapidly expanding cities has placed increasing stress on the water supply as watersheds are affected and ground water tables fall. Nonetheless, Colombia has large reserves of freshwater and is the fourth country in the world by magnitude of total freshwater supply.[25]

Participants in the country's armed conflict have also contributed to the pollution of the environment. Illegal armed groups have deforested large areas of land to plant illegal crops, with an estimated 99,000 hectares used for the cultivation of coca in 2007,[26] while in response the government has fumigated these crops using hazardous chemicals. Insurgents have also destroyed oil pipelines creating major ecological disasters[cần dẫn nguồn].

History[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Pre-Columbian era[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Approximately 10,000 BC, hunter-gatherer societies existed near present-day Bogotá (at "El Abra" and "Tequendama") which traded with one another and with cultures living in the Magdalena River Valley.[27] Beginning in the first millennium BC, groups of Amerindians developed the political system of "cacicazgos" with a pyramidal structure of power headed by caciques. Within Colombia, the two cultures with the most complex cacicazgo systems were the Tayronas in the Caribbean Region, and the Muiscas in the highlands around Bogotá, both of which were of the Chibcha language family. The Muisca people are considered to have had one of the most developed political systems in South America, after the Incas.[28]

Spanish discovery, conquest, and colonization[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Spanish explorers made the first exploration of the Caribbean littoral in 1499 led by Rodrigo de Bastidas. Christopher Columbus navigated near the Caribbean in 1502. In 1508, Vasco Núñez de Balboa started the conquest of the territory through the region of Urabá. In 1513, he was the first European to discover the Pacific Ocean, which he called Mar del Sur (or "Sea of the South") and which in fact would bring the Spaniards to Peru and Chile.

Alonso de Lugo (who had sailed with Columbus) reached the Guajira Peninsula in 1500. Santa Marta was founded in 1525, and Cartagena in 1533. Gonzalo Jiminez de Quesada led an expedition to the interior in 1535, and founded the "New City of Granada", the name soon changed to "Santa Fé de Bogotá." Two other notable journeys by Spaniards to the interior took place in the same period. Sebastian de Belalcazar, conqueror of Quito, traveled north and founded Cali in 1536 and Popayán in 1537; Nicolas Federman crossed Llanos Orientales and went over the Eastern Cordillera.[29]

The territory's main population was made up of hundreds of tribes of the Chibchan and Carib, currently known as the Caribbean people, whom the Spaniards conquered through warfare and alliances, while resulting disease such as smallpox, and the conquest and ethnic cleansing itself caused a demographic reduction among the indigenous people.[30] In the 16th century, Europeans began to bring slaves from Africa.

Independence from Spain[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Since the beginning of the periods of Conquest and Colonization, there were several rebel movements under Spanish rule, most of them either being crushed or remaining too weak to change the overall situation. The last one which sought outright independence from Spain sprang up around 1810, following the independence of St. Domingue in 1804 (present-day Haiti), who provided a non-negligible degree of support to the eventual leaders of this rebellion: Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Paula Santander.

A movement initiated by Antonio Nariño, who opposed Spanish centralism and led the opposition against the viceroyalty, led to the independence of Cartagena in November 1811. This led to the formation of two independent governments which fought a civil war, a period known as La Patria Boba. The following year Nariño proclaimed the United Provinces of New Granada, headed by Camilo Torres Tenorio. Despite the successes of the rebellion, the emergence of two distinct ideological currents among the liberators (federalism and centralism) gave rise to an internal clash between these two, thus contributing to the reconquest of territory by the Spanish, allowing restoration of the viceroyalty under the command of Juan de Samano, whose regime punished those who participated in the uprisings. This stoked renewed rebellion, which, combined with a weakened Spain, made possible a successful rebellion led by Simón Bolívar, who finally proclaimed independence in 1819. The pro-Spanish resistance was finally defeated in 1822 in the present territory of Colombia and in 1823 in Venezuela.

The territory of the Viceroyalty of New Granada became the Republic of Colombia organized as a union of Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela (Panama was then an integral part of Colombia). The Congress of Cucuta in 1821 adopted a constitution for the new Republic. The first President of Colombia was the Venezuelan-born Simón Bolívar, and Francisco de Paula Santander was Vice President. However, the new republic was very unstable and ended with the rupture of Venezuela in 1829, followed by Ecuador in 1830.

Post-independence and republicanism[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Sự chia rẽ chính trị và lãnh thổ trong nội bộ đã dẫn tới sự ly khai của Venezuela và Quito (Ecuador ngày nay) năm 1830. Cái gọi là "Khu Cundinamarca" đã chấp nhận cái tên "Nueva Granada", cacis tên mà nó giữ cho đến tận năm 1856 khi nó trở thanhg "Confederación Granadina" (liên bang Grenadine). Sau cuộc nội chiến kéo dài hai năm năm 1863, "Hợp chúng quốc Colombia" được thành lập và tồn tại tới năm 1886, khi cuối cùng đất nước này trở thành Cộng hòa Colombia. Sự chia rẽ nội bộ tiếp tục diễn ra giữa giữa các lực lượng chính trị lưỡng đảng, thingr thoảng bùng nổ những cuộc nội chiến rất đãm máu, nổi bật nhất là cuộc Nội chiến một nghìn ngày (1899–1902).

việc này, cùng với ý định chí phối khu vực của Mỹ (đặc biệt là sự xây dựng và quản lý kênh đào Panama) dẫn đến sự tách ra của vùng Panama năm 1903 sự thành lập của nó như là một quốc gia. Mỹ trả cho Colombia 25.000.000 đo la năm 1921, bảy năm sau sự hoàn thành kênh đào, cho sự đền bù vì vai trò của tổng thống Roosevelt trong sự thành lập của Panama, và Colombia công nhân Panama dưới các điều khoản của hiệp ước Thomson-Urrutia. Colombia bị sa lầy vào cuộc chiến tranh kéo dài một năm với Peru về tranh chấp lãnh thổ liên quan tới khu Amazonas và thủ phủ Leticia của nó.

Ngay sau đó, Colombia đạt được một mức độ tương đối về sự ổn định chính trị, nhưng nó bị gián đoạn bởi một cuộc xung đột đẫm máu that took place cuối năm những năm 1940 và đầu những năm 1950, một giai đoạn biết đến như La Violencia ("sự bạo lực"). nguyên nhân chính của nó sự căng thẳng tăng lên giữa hai đảng chính trị lớn nhất, sau đó bùng nổ sau cuộc ám sát ứng cử viên chủ tịch đảng tự do Jorge Eliécer Gaitán 9 tháng 4 năm 1948. sự ám sát này gây ra caused sự náo loạn tại Bogotá và trở nên được biết như El Bogotazo. bạo lực từ sự hỗn loạn này lan ra khắp đất nước và cuwpwos đi sinh mạng của ít nhất 180,000 người Colombia.

Từ năm 1953 đến 1964 tình trạng bạo lực giữa hai đảng phái chính trị lần đầu tiên giảm sút khi Gustavo Rojas lật đổ tổng thống Colombia trong một cuộc đảo chính và đàm phán với phe du kích, rồi sau đó dưới quyền điều hành hội đồng quân sự của tướng Gabriel París Gordillo.

Sau cuộc đảo chính của Rojas hai đảng chính trị là đảng bảo thủ Colombia và đảng tụ do Colombia đồng ý với sự thành lập một "mặt trận quốc gia", theo đó hai đảng tự do và bảo thủ sẽ cùng nhau cầm quyền. Vị trí tổng thổng sẽ được quyết định bởi một sự luân phiên chủ tịch tự do và bảo thủ mỗi 4 năm trong mười sáu năm; hai đảng sẽ có sự bình đẳng trong mọi cơ quan bầu cử. Hỗi đồng quốc gia đã chấm dứt "La Violencia", chính phủ hội đồng quốc gia cố gắng xây dựng các cuộc cải cách kinh tế xã hội sâu rộng trong sự hợp tác bằng khối liên minh vì tiến bộ. Cuối cùng, sự mâu thuẫn giữa mỗi chính phủ tự do và bảo thủ kế tiếp nhau đã tạo ra những kết quả lẫn lộn rõ rệt. Mặc dù có sự phát triển trong các lĩnh vực đôi chút, nhưng nhiều vấn chính trị và xã hội vẫn tồn tại, và nhiều nhóm du kích được chính thức thành lập như FARC, ELN và M-19 để chống lại bộ máy chính quyền và chính phủ. những nhóm du kích này bị chế nự bởi học thuyết Mác.

nổi bất trong cuối những năm 1970 là các tổ chức ma túy hung tợn và đầy quyền lực phát triển thêm trong những năm 1980 và 1990. Tổ chức ma túy Medellín dưới quyền Pablo Escobar và Tổ chức ma túy Cali nói riêng, cố gắng chi phối chính trị, kinh tế và xã hội Colombia trong giai đoạn này. Các tổ chức này cũng tài trợ và chi phối các nhóm vũ trang bất hợp pháp khác khắp phạm vi chính trị. Vài kẻ thù trong số những liên minh này với các nhóm du kích và tọa thành hay chi phối các nhóm bán quân sự.

Hiến pháp mới của Colombia năm 1991 được thông qua sau khi được dự thảo bởi hội đồng lập hiến Colombia. Hiến pháp bao gồm các điều khoản chính về các quyền giới tính, con người, dân tộc và chính trị. Ban đầu hiến pháp mới ngăn cấm sự dẫn độ công dân Colombia, các cáo trạng khiến các tổ chức ma túy đã vận động hành lang cho những điều khoản hiến pháp; sự dẫn độ được chấp nhận lại năm 1996 khi các điều khoản bị bãi bỏ. Các tổ chức ma túy trước đây đã xúc tiến một chiến dịch hung bạo chống lại sự dẫn độ, cầm đầu nhiều cuộc tấn công khủng bố và hành hình kiểu mafia. Họ cũng cố gắng chi phối kết cấu chính trị và chính phủ Colombia bằng sự tham nhũng, như trong vụ scandal 8000 Process.

trong những năm gần đây, Colombia vẫn bị quây rầy bởi tác động của việc buôn bán ma túy, những sự nổi loạn du kích như FARC, and và các nhóm bán quân sự ví dụ AUC, những tổ chức này cùng với các đảng phái nhỏ đã tham gia vào một cuộc xung đột vũ trang nội bộ đẫm máu. Tổng thống Andrés Pastrana và FARC cố gắng dàn xếp một giải pháp cuộc xung đột từ năm 1999 đến 2002. Chính phủ dựng lên một khu vực "phi quân sự", nhưng tình trạng căng thẳng lặp lại và sự khủng hoảng dẫn đến chính quyền Pastrana phải kết thúc sự mà cuộc đàm phán đã trở nên vô ích. Pastrana cũng bắt đầu thi hành sáng kiến kế hoạch Colombia, với hai mục tiêu châm dứt cuộc xung đột vũ trang và đề xướng một chiến lược chống ma túy toàn diện.

During the presidency of Álvaro Uribe, the government applied more military pressure on the FARC and other outlawed groups. After the offensive, which was supported by foreign aid provided by the United States, many security indicators improved. Reported kidnappings showed a steep decrease (from 3,700 in the year 2000 to 172 in 2009 (Jan.-Oct.)) and so did intentional homicides (from 28,837 in 2002 to 15,817 in 2009, according to police, while the health system reported a decline from 28,534 to 17,717 during the same period). Kidnappings suffered a steady decline for almost a decade until a 2010 increase saw 280 cases reported between January and October, most of which were concentrated in the Medellín area.[31][32][33][34] According to official statistics, guerrillas were reduced from 24,000 fighters in 2002 to 9,500 in 2010.[35] While rural areas and jungles remained dangerous, the overall reduction of violence led to the growth of internal travel and tourism after security conditions improved.[36]

The 2006–2007 Colombian parapolitics scandal emerged from the revelations and judicial implications of past and present links between paramilitary groups, mainly the AUC, and some government officials and many politicians, most of them allied to the governing administration.[37]

Government[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The government of Colombia takes place within the framework of a presidential representative democratic republic as established in the Constitution of 1991. In accordance with the principle of separation of powers, government is divided into three branches: the executive branch, the legislative branch and the judicial branch.

The head of the executive branch is the President of Colombia who serves as both head of state and head of government, followed by the Vice President and the Council of Ministers. The president is elected by popular vote to serve four-year terms and is currently limited to a maximum of two such terms (increased from one in 2005). At the provincial level executive power is vested in department governors, municipal mayors and local administrators for smaller administrative subdivisions, such as corregidores or corregimientos.

The legislative branch of government is composed by the Senate and the House of Representatives. The 102-seat Senate is elected nationally and the Representatives are elected by every region and minority groups.[38] Members of both houses are elected two months before the president, also by popular vote and to serve four-year terms. At the provincial level the legislative branch is represented by department assemblies and municipal councils. All regional elections are held one year and five months after the presidential election. The judicial branch is headed by the Supreme Court, consisting of 23 judges divided into three chambers (Penal, Civil and Agrarian, and Labour). The judicial branch also includes the Council of State, which has special responsibility for administrative law and also provides legal advice to the executive, the Constitutional Court, responsible for assuring the integrity of the Colombian constitution, and the Superior Council of Judicature, responsible for auditing the judicial branch. Colombia operates a system of civil law, which since 2005 has been applied through an adversarial system.

Administrative divisions[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Click on a department on the map below to go to its article. Bản mẫu:Colombia map clickable

|

|

Colombia is divided into 32 departments and one capital district, which is treated as a department (Bogotá also serves as the capital of the department of Cundinamarca). Departments are subdivided into municipalities, each of which is assigned a municipal seat, and municipalities are in turn subdivided into corregimientos. Each department has a local government with a governor and assembly directly elected to four-year terms. Each municipality is headed by a mayor and council, and each corregimiento by an elected corregidor, or local leader.

In addition to the capital nine other cities have been designated districts (in effect special municipalities), on the basis of special distinguishing features. These are Barranquilla, Cartagena, Santa Marta, Cúcuta, Popayán, Bucaramanga, Tunja, Turbo, Buenaventura and Tumaco. Some departments have local administrative subdivisions, where towns have a large concentration of population and municipalities are near each other (for example in Antioquia and Cundinamarca). Where departments have a low population and there are security problems (for example Amazonas, Vaupés and Vichada), special administrative divisions are employed, such as "department corregimientos", which are a hybrid of a municipality and a corregimiento.

Foreign affairs[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The foreign affairs of Colombia are headed by the President of Colombia and managed by the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Colombia has diplomatic missions in all continents and is also represented in multilateral organizations at the following locations:

- Brussels (Mission to the European Union)

- Geneva (Permanent Missions to the United Nations and other international organizations)

- Montevideo (Permanent Missions to the Latin American Integration Association and Mercosur)

- Nairobi (Permanent Missions to the United Nations and other international organizations)

- New York (Permanent Mission to the United Nations)

- Paris (Permanent Mission to UNESCO)

- Rome (Permanent Mission to the Food and Agriculture Organization)

- Washington, D.C. (Permanent Mission to the Organization of American States)

The foreign relations of Colombia are mostly concentrated on combating the illegal drug trade, the fight against terrorism, improving Colombia's image in the international community, expanding the international market for Colombian products, and environmental issues. Colombia receives special military and commercial co-operation and support in its fight against internal armed groups from the United States, mainly through Plan Colombia, as well as special financial preferences from the European Union in certain products.

Colombia was one of the 12 countries that joined the UNASUR when it was created. UNASUR is supposed to be modeled like the European Union having free trade agreements with the members, free movement of people, a common currency, and also a common passport. Colombia as well as all the other members of UNASUR have had some problems with the integration due to the 2008 Andean diplomatic crisis.

Colombia is a member of the Andean Community of Nations and the Union of South American Nations.

Colombians need tourist visa for 180 countries[39] and do not need tourist visa for 15 countries.[40]

Defense[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The executive branch of government has responsibility for managing the defense of Colombia, with the President commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

The Colombian military is divided into three branches: the National Army of Colombia; the Colombian Air Force; and the Colombian National Armada. The National Police functions as a gendarmerie, operating independently from the military as the law enforcement agency for the entire country. Each of these operates with their own intelligence apparatus separate from the national intelligence agency, the Administrative Department of Security.

The National Army is formed by divisions, regiments and special units; the National Armada by the Colombian Naval Infantry, the Naval Force of the Caribbean, the Naval Force of the Pacific, the Naval Force of the South, Colombia Coast Guards, Naval Aviation and the Specific Command of San Andres y Providencia; and the Air Force by 13 air units. The National Police has a presence in all municipalities.

Politics[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

For over a century Colombian politics were monopolized by the Liberal Party (founded in 1848 on an anti-clerical, broadly economically liberal and federalist platform), and the Conservative Party (founded in 1849 espousing Catholicism, protectionism, and centralism). This culminated in the formation of the National Front (1958–1974), which formalized arrangements for an alternation of power between the two parties and excluded non-establishment alternatives (thereby fueling the nascent armed conflict).

By the time of the dissolution of the National Front, traditional political alignments had begun to fragment. This process has continued since, and the consequences of this are exemplified by the results of the presidential election of 28 May 2006, which was won with 62% of the vote by the incumbent, Álvaro Uribe. President Uribe was from a Liberal background but he campaigned as part of the Colombia First movement with the support of the Conservative Party, and his hard line on security issues and liberal economics place him on the right of the modern political spectrum[cần dẫn nguồn].

In second place with 22% was Carlos Gaviria of the Alternative Democratic Pole, a newly formed social democratic alliance which includes elements of the former M-19 guerrilla movement. Horacio Serpa of the Liberal Party achieved third place with 12%. Meanwhile in the congressional elections held earlier that year the two traditional parties secured only 93 out of 268 seats available.

Despite a number of controversies, most notably the ongoing parapolitics scandal, dramatic improvements in security and continued strong economic performance have ensured that former President Álvaro Uribe remained popular among Colombian people, with his approval rating peaking at 85%, according to a poll in July 2008.[41] However, having served two terms, he was constitutionally barred from seeking re-election in 2010. The Colombian Congress, with overwhelming support of the Colombian people, had attempted to hold a referendum allowing a vote that would overturn the 2-term limit for presidents, but this attempt was ruled unconstitutional by the Colombian constitutional court on February 27, 2010. President Uribe stated that he respects the decision, one that cannot be appealed.

On presidential elections performed as of May 30, 2010 people voted 46% [42] for the former Minister of defense Juan Manuel Santos for being the president from 2010 to 2014, but according to the current laws, since he does not have 50% of the votes, there was a second round on June 20, 2010 against the second most voted candidate, Antanas Mockus with 21%.[42] The winning candidate was Juan Manuel Santos, who became Colombia's president beginning on August 7, 2010.

Economy[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In spite of the difficulties presented by serious internal armed conflict, Colombia's market economy grew steadily in the latter part of the twentieth century, with gross domestic product (GDP) increasing at an average rate of over 4% per year between 1970 and 1998. The country suffered a recession in 1999 (the first full year of negative growth since the Great Depression), and the recovery from that recession was long and painful. However, in recent years growth has been impressive, reaching 8.2% in 2007, one of the highest rates of growth in Latin America. Meanwhile the Colombian stock exchange climbed from 1,000 points at its creation in July 2001 to over 7,300 points by November 2008.[43]

According to International Monetary Fund estimates, in 2010 Colombia's GDP (PPP) was US$429.866 billion (28th in the world and third in South America). Adjusted for purchasing power parity, GDP per capita stands at $7,968, placing Colombia 82nd in the world. However, in practice this is relatively unevenly distributed among the population, and, in common with much of Latin America, Colombia scores poorly according to the Gini coefficient, with UN figures placing it 119th out of 126 countries. In 2003 the richest 20% of the population had a 62.7% share of income/consumption and the poorest 20% just 2.5%, and 17.8% of Colombians live on less than $2 a day.[44]

Government spending is 37.9% of GDP.[7] Almost a quarter of this goes towards servicing the country's relatively high government debt, estimated at 52.8% of GDP in 2007.[7][44] Other problems facing the economy include weak domestic and foreign demand, the funding of the country's pension system, and unemployment (10.8% in November 2008).[43] Inflation has remained relatively low in recent years, standing at 5.5% in 2007.[7]

Historically an agrarian economy, Colombia urbanised rapidly in the twentieth century, by the end of which just 22.7% of the workforce were employed in agriculture, generating just 11.5% of GDP. 18.7% of the workforce are employed in industry and 58.5% in services, responsible for 36% and 52.5% of GDP respectively.[7] Colombia is rich in natural resources, and its main exports include petroleum, coal, coffee and other agricultural produce, and gold.[45] Colombia is also known as the world's leading source of emeralds,[46] while over 70% of cut flowers imported by the United States are Colombian.[47] Principal trading partners are the United States (a controversial free trade agreement with the United States is currently awaiting approval by the United States Congress), Venezuela and China.[7] All imports, exports, and the overall balance of trade are at record levels, and the inflow of export dollars has resulted in a substantial re-valuation of the Colombian peso.

Economic performance has been aided by liberal reforms introduced in the early 1990s and continued during the presidency of Álvaro Uribe, whose policies included measures designed to bring the public sector deficit below 2.5% of GDP. In 2008, The Heritage Foundation assessed the Colombian economy to be 61.9% free, an increase of 2.3% since 2007, placing it 67th in the world and 15th out of 29 countries within the region.[48]

Meanwhile the improvements in security resulting from President Uribe's controversial "democratic security" strategy have engendered an increased sense of confidence in the economy. On 28 May 2007 the American magazine BusinessWeek published an article naming Colombia "the most extreme emerging market on Earth".[49] Colombia's economy has improved in recent years. Investment soared, from 15% of GDP in 2002 to 26% in 2008. private business has retooled. However unemployment at 12 % and the poverty rate at 46% in 2009 are above the regional average.[50]

According to a recent World Bank report, doing business is easiest in Manizales, Ibagué and Pereira, and more difficult in Cali and Cartagena. Reforms in custom administration have helped reduce the amount of time it takes to prepare documentation by over 60% for exports and 40% for imports compared to the previous report. Colombia has taken measures to address the backlog in civil municipal courts. The most important result was the dismissal of 12.2% of inactive claims in civil courts thanks to the application of Law 1194 of 2008 (Ley de Desistimiento Tácito).[51]

Tourism[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

For many years serious internal armed conflict deterred tourists from visiting Colombia, with official travel advisories warning against travel to the country. However, in recent years numbers have risen sharply, thanks to improvements in security resulting from President Álvaro Uribe's "democratic security" strategy, which has included significant increases in military strength and police presence throughout the country and pushed rebel groups further away from the major cities, highways and tourist sites likely to attract international visitors. Foreign tourist visits were predicted to have risen from 0.5 million in 2003 to 1.3 million in 2007,[52] while Lonely Planet picked Colombia as one of their top ten world destinations for 2006.[53] Colombia Minister for Industry, Trade and Tourism Luis Guillermo Plata said his country had received 2,348,948 visitors in 2008. In 2010 Colombia recieved less than 1,5 million foreign visitors, according to official statistics.[54]

In November 2010 the U.S. State Department travel warning for the country stated that security conditions had improved significantly in recent years and kidnappings had been noticeably reduced from their previous peak, but cautioned travelers about continuing terrorist threats and the dangers of common crime, including hostage-taking. Rising murder rates in Cali and Medellín were also highlighted and U.S. citizens were urged to travel between cities by air instead of using ground transportation.[55]>

-

Fortifications of the old city of Cartagena, one of the seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Colombia.

-

Arrecifes beach in the Tayrona National Natural Park, one of the main ecotourist destinations.

-

Downtown Bogotá.

-

Pueblito Paisa. (Medellín)

-

The "Eje Cafetero"

-

Cali night.

-

La Candelaria, Bogotá's historic district.

Popular tourist attractions include the historic Candelaria district of central Bogotá, the walled city and beaches of Cartagena, the colonial towns of Santa Fe de Antioquia, Popayán, Villa de Leyva and Santa Cruz de Mompox, and the Las Lajas Sanctuary and the Salt Cathedral of Zipaquirá. Tourists are also drawn to Colombia's numerous festivals, including Medellín's Festival of the Flowers, the Barranquilla Carnival, the Carnival of Blacks and Whites in Pasto and the Ibero-American Theater Festival in Bogotá. Meanwhile, because of the improved security, Caribbean cruise ships now stop at Cartagena and Santa Marta.

The great variety in geography, flora and fauna across Colombia has also resulted in the development of an ecotourist industry, concentrated in the country's national parks. Popular ecotourist destinations include: along the Caribbean coast, the Tayrona National Natural Park in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountain range and Cabo de la Vela on the tip of the Guajira Peninsula; the Nevado del Ruiz volcano, the Cocora valley and the Tatacoa Desert in the central Andean region; Amacayacu National Park in the Amazon River basin; and the Pacific islands of Malpelo and Gorgona. Colombia is home to seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Transportation[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Colombia has a network of national highways maintained by the Instituto Nacional de Vías or INVIAS (National Institute of Roadways) government agency under the Ministry of Transport. The Pan-American Highway travels through Colombia, connecting the country with Venezuela to the east and Ecuador to the south.

Colombia's main airports are El Dorado International Airport in Bogotá, Jose Maria Cordova International Airport in Medellín, Alfonso Bonilla Aragon International Airport in Cali, Ernesto Cortissoz International Airport in Barranquilla, Matecaña International Airport in Pereira, and Rafael Nuñez International Airport in Cartagena. El Dorado International Airportis the busiest airport in Latin America based upon the number of flights and the weight of goods transported.[56] Several national airlines (Avianca, AeroRepública, AIRES, SATENA and EasyFly,), and international airlines (such as Iberia, American Airlines, Varig, Copa, Continental, Delta, Air Canada, Spirit, Lufthansa, Air France, Aerolíneas Argentinas, Aerogal, TAME, TACA, JetBlue Airways, LAN Airlines) operate from El Dorado. Because of its central location in Colombia and America, it is preferred by national land transportation providers, as well as national and international air transportation providers.

Urban transport systems have been developed in Bogotá and Medellín. Traffic congestion in Bogotá has been greatly exacerbated by the lack of rail transport. However, this problem has been alleviated somewhat by the development of the TransMilenio Bus Rapid System and the restriction of vehicles through a daily, rotating ban on private cars depending on plate numbers. Bogotá's system consists of bus and minibus services managed by both private- and public-sector enterprises. Since 1995 Medellín has had a modern urban railway referred to as the Metro de Medellín, which also connects with the cities of Itagüí, Envigado, and Bello. An elevated cable car system, Metrocable, was added in 2004 to link some of Medellín's poorer mountainous neighborhoods with the Metro de Medellín. A bus rapid-transit system called Transmetro, similar to Bogotá's TransMilenio, will begin operating in Barranquilla by late 2007. Cali's streets remain under construction as a new public-transit system called the Massive Integration of the West is being built.

Colombia dry canal[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Trung Quốc and Colombia have discussed a Panama Canal rival, a 'Dry Canal' a 220 km rail link between the Pacific and a new city near Cartagena. China is Colombia's second largest trade partner after the USA. Colombia is also the world's fifth-largest coal producer, but most is currently exported via Atlantic ports while demand is growing fastest across the Pacific. A dry canal could make Colombia a hub where imported Chinese goods would be assembled for re-export throughout the Americas and Latin American raw materials would begin the return journey to China.[57]

Demographics[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

With an estimated 46 million people in 2008, Colombia is the third-most populous country in Latin America, after Brazil and Mexico. It is also home to the fourth-largest number of Spanish speakers in the world after Mexico, the United States, and Spain. It is slightly ahead of Argentina. The population increased at a rate of 1.9% between 1975 and 2005, predicted to drop to 1.2% over the next decade. Colombia is projected to have a population of 50.7 million by 2015. These trends are reflected in the country's age profile. In 2005 over 30% of the population was under 15 years old, compared to just 5.1% aged 65 and over.

The population is concentrated in the Andean highlands and along the Caribbean coast. The nine eastern lowland departments, comprising about 54% of Colombia's area, have less than 3% of the population and a density of less than one person per square kilometer (two persons per square mile). Traditionally a rural society, movement to urban areas was very heavy in the mid-twentieth century, and Colombia is now one of the most urbanized countries in Latin America. The urban population increased from 31% of the total in 1938 to 60% in 1975, and by 2005 the figure stood at 72.7%.[44][58] The population of Bogotá alone has increased from just over 300,000 in 1938 to approximately 8 million today. In total thirty cities now have populations of 100,000 or more. As of 2010 Colombia has the world's largest populations of internally displaced persons (IDPs), estimated up to 4.5 million people.[59][60]

| Thành thị lớn nhất của Colombia Source? | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hạng | Tên | Department | Dân số | ||||||

Bogotá  Medellín |

1 | Bogotá | Distrito Capital | 8,840,116 |  Cali  Barranquilla | ||||

| 2 | Medellín | Antioquia | 3,374,340 | ||||||

| 3 | Cali | Valle del Cauca | 2,728,431 | ||||||

| 4 | Barranquilla | Atlántico | 1,946,359 | ||||||

| 5 | Cartagena, Colombia | Bolívar | 1,198,665 | ||||||

| 6 | Cúcuta | Norte de Santander | 918,942 | ||||||

| 7 | Pereira, Colombia | Risaralda | 576,329 | ||||||

| 8 | Bucaramanga | Santander | 566,598 | ||||||

| 9 | Ibagué | Tolima | 518,401 | ||||||

| 10 | Santa Marta | Magdalena | 455,270 | ||||||

Colombia is ranked sixth in the world in the Happy Planet Index.

Ethnic groups[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The census data in Colombia does not record ethnicity, other than that of those identifying themselves as members of particular minority ethnic groups, so overall percentages are essentially estimates from other sources and can vary from one to another.[61] According to the CIA World Factbook, the majority of the population (58%) is Mestizo, or of mixed European and Amerindian ancestry. Approximately 20% of the population is of European ancestry (predominantly Spanish, partly Italian, Portuguese, and German). The CIA World Factbook also states that 14% of Colombia's total population is of mixed African and European ancestry, with 3% being of mixed African and Amerindian ancestry, and 4% having primarily African ancestry. Indigenous Amerindians comprise only 1% of the population.[7] Other sources claim that up to 29% of Colombians (13 million people) have some African ancestry.[62]

The overwhelming majority of Colombians speak Spanish (see also Colombian Spanish), but in total 101 languages are listed for Colombia in the Ethnologue database, of which 80 are spoken today. Most of these belong to the Chibchan, Arawak and Cariban language families. The Quechua language, spoken in the Andes region of the country, has also extended more northwards into Colombia, mainly in urban centers of major cities. There are currently about 500,000 speakers of indigenous languages.[63]

Indigenous peoples[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Before the Spanish colonization of what is now Colombia, the territory was home to a significant number of indigenous peoples. Many of these were absorbed into the mestizo population, but the remainder currently represents over eighty-five distinct cultures. 567 reserves (resguardos) established for indigenous peoples occupy 365,004 square kilometres (over 30% of the country's total) and are inhabited by more than 800,000 people in over 67,000 families.[65] The 1991 constitution established their native languages as official in their territories, and most of them have bilingual education (native and Spanish).

Some of the largest indigenous groups are the Wayuu,[66] the Arhuacos, the Muisca, the Kuna, the Paez, the Tucano and the Guahibo. Cauca, La Guajira and Guainia have the largest indigenous populations.

The Organización Nacional Indígena de Colombia (ONIC) is an organization representing the indigenous peoples of Colombia, who comprise some 800,000 people or approximately 2% of the population. The organization was founded at the first National Indigenous Congress in 1982.

In 1991, Colombia signed and ratified the current international law concerning indigenous peoples, Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989.[67]

Immigrant groups[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The first and most substantial wave of modern immigration to Colombia consisted of Spanish colonists, following the arrival of Europeans in 1499. However a low number of other Europeans and North Americans migrated to the country in the late 19th and early twentieth centuries, and, in smaller numbers, Poles, Lithuanians, English, Irish, and Croats during and after the Second World War.

Many immigrant communities have settled on the Caribbean coast, in particular recent immigrants from the Middle East. Barranquilla (the largest city of the Colombian Caribbean) and other Caribbean cities have the largest populations of Lebanese and Arabs, Sephardi Jews, Roma. There are also important communities of Chinese and Japanese[cần dẫn nguồn].

Black Africans were brought as slaves, mostly to the coastal lowlands, beginning early in the 16th century and continuing into the 19th century. Large Afro-Colombian communities are found today on the Caribbean and Pacific coasts. The population of the department of Chocó, running along the northern portion of Colombia's Pacific coast, is over 80% black.[68]

Impact of armed conflict on civilians[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Around one third of the people in Colombia have been affected in some way by the ongoing armed conflict. Those with direct personal experience make up 10% of the population and many others also report suffering a range of serious hardships. Overall, 31% have been affected on a personal level or as a result of the wider consequences of the conflict.[69]

During the 1990s, an estimated 35,000 people died as a result of the armed conflict.[70] Trade unions in Colombia are included among the victimized groups with over 2,800 of their members being murdered between 1986 and 2010.[71]

Religion[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) does not collect religious statistics, and accurate reports are difficult to obtain. However, based on various studies, more than 95% of the population adheres to Christianity,[72] the vast majority of which (between 81% and 90%) are Roman Catholic. About 1% of Colombians adhere to indigenous religions and under 1% to Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism. However, despite high numbers of adherents, around 60% of respondents to a poll by El Tiempo reported that they did not practice their faith actively.[73]

While Colombia remains an overwhelmingly Roman Catholic country, the Colombian constitution guarantees freedom and equality of religion.[74] Religious groups are readily able to obtain recognition as organized associations, although some smaller ones have faced difficulty in obtaining the additional recognition required to offer chaplaincy services in public facilities and to perform legally recognised marriages.[73]

Health[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Life expectancy at birth in 2005 was 72.3; 2.1% would not reach the age of 5, 9.2% would not reach the age of 40.[44] Health standards in Colombia have improved greatly since the 1980s. A 1993 reform transformed the structure of public health-care funding by shifting the burden of subsidy from providers to users. As a result, employees have been obligated to pay into health plans to which employers also contribute. Although this new system has widened population coverage by the social and health security system from 21 percent (pre-1993) to 56 percent in 2004 and 66 percent in 2005, health disparities persist, with the poor continuing to suffer relatively high mortality rates. In 2002 Colombia had 58,761 physicians, 23,950 nurses, and 33,951 dentists; these numbers equated to 1.35 physicians, 0.55 nurses, and 0.78 dentists per 1,000 population, respectively. In 2005 Colombia was reported to have only 1.1 physicians per 1,000 population, as compared with a Latin American average of 1.5. The health sector reportedly is plagued by rampant corruption, including misallocation of funds and evasion of health-fund contributions.[75]

Education[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The educational experience of many Colombian children begins with attendance at a preschool academy until age 6 (Educación preescolar). Basic education (Educación básica) is compulsory by law.[76] It has two stages: Primary basic education (Educación básica primaria) which goes from 1st to 5th grade and usually it encompasses children from 6 to 10 years old, and Secondary basic education (Educación básica secundaria), which goes from 6th to 9th grade. Basic education is followed by Middle vocational education (Educación media vocacional) that comprehends 10th and 11th grade. It may have different vocational training modalities or specialties (academic, technical, business, and so on.) according to the curriculum adopted by each school. However in many rural areas, teachers are poorly qualified, and only the five years of primary schooling are offered. The school year can extend from February to November or from August to June, and in many public schools attendance is split into morning and afternoon "shifts", in order to accommodate the large numbers of children.[77]

After the successful completion of all the basic and middle education years, a high-school diploma is granted. The high-school graduate is known as a bachiller, because secondary basic school and middle education are traditionally considered together as a unit called bachillerato (6th to 11th grade). Students in their final year of middle education take the ICFES test in order to gain access to Superior education (Educación superior). This superior education includes undergraduate professional studies, technical, technological and intermediate professional education, and post-graduate studies.

Bachilleres (high-school graduates) may enter into a professional undergraduate career program offered by a university; these programs last up to 5 years (or less for technical, technological and intermediate professional education, and post-graduate studies), even up to 6–7 years for some careers, such as medicine. In Colombia, there is not an institution such as college; students go directly into a career program at a university or any other educational institution to obtain a professional, technical or technological title. Once graduated from the university, people are granted a (professional, technical or technological) diploma and licensed (if required) to practice the career they have chosen. For some professional career programs, students are required to take the SABER-PRO test in their final year of undergraduate academic education.[78]

Public spending on education as a proportion of gross domestic product in 2006 was 4.7% — one of the highest rates in Latin America — as compared with 2.4% in 1991. This represented 14.2% of total government expenditure.[44][79] In 2006, the primary and secondary net enrollment rates stood at 88% and 65% respectively, slightly below the regional average. School life expectancy was 12.4 years.[79] A total of 92.3% of the population aged 15 and older were recorded as literate, including 97.9% of those aged 15–24, both figures slightly higher than the regional average.[79] However, literacy levels are considerably lower in rural areas.[80]

-

Ernesto Guhl library in the National University of Colombia. The National University is the largest state-run university in Colombia.

-

Universidad Externado de Colombia in Bogotá

Culture[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Colombia lies at the crossroads of Latin America and the broader American continent, and as such has been hit by a wide range of cultural influences. Native American, Spanish and other European, African, American, Caribbean, and Middle Eastern influences, as well as other Latin American cultural influences, are all present in Colombia's modern culture. Urban migration, industrialization, globalization, and other political, social and economic changes have also left an impression.

Historically, the country's imposing landscape left its various regions largely isolated from one another, resulting in the development of very strong regional identities, in many cases stronger than the national. Modern transport links and means of communication have mitigated this and done much to foster a sense of nationhood, but social and political instability, and in particular fears of armed groups and bandits on intercity highways, have contributed to the maintenance of very clear regional differences. Accent, dress, music, food, politics and general attitude vary greatly between the Bogotanos and other residents of the central highlands, the paisas of Antioquia and the coffee region, the costeños of the Caribbean coast, the llaneros of the eastern plains, and the inhabitants of the Pacific coast and the vast Amazon region to the south east.

-

Colombians dancing Salsa

-

Fiesta in Palenque. Afro-Colombian tradition from San Basilio de Palenque, a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity since 2005.

-

A "Chiva" in New York city

An inheritance from the colonial era, Colombia remains a deeply Roman Catholic country and maintains a large base of Catholic traditions which provide a point of unity for its multicultural society. Colombia has many celebrations and festivals throughout the year, and the majority are rooted in these Catholic religious traditions. However, many are also infused with a diverse range of other influences. Prominent examples of Colombia's festivals include the Barranquilla Carnival, the Carnival of Blacks and Whites, Medellín's Festival of the Flowers and Bogotá's Ibero-American Theater Festival

The mixing of various different ethnic traditions is reflected in Colombia's music and dance. The most well-known Colombian genres are cumbia and vallenato, the latter now strongly influenced by global pop culture. A powerful and unifying cultural medium in Colombia is television. Most famously, the telenovela Betty La Fea has gained international success through localized versions in the United States, Mexico, and elsewhere. Television has also played a role in the development of the local film industry.

As in many Latin American countries, Colombians have a passion for football. The Colombian national football team is seen as a symbol of unity and national pride, though local clubs also inspire fierce loyalty and sometimes-violent rivalries. Colombia has "exported" many famous players, such as Freddy Rincón, Carlos Valderrama, Iván Ramiro Córdoba, and Faustino Asprilla. Other Colombian athletes have also achieved success, including Formula 1 Racing's Juan Pablo Montoya, Major League Baseball's Edgar Rentería and Orlando Cabrera, and the PGA Tour's Camilo Villegas.

Other famous Colombians include the Nobel Prize winning author Gabriel García Márquez, the artist Fernando Botero, the writers Fernando Vallejo, Laura Restrepo, Álvaro Mutis and James Cañón, the musicians Shakira, Juanes, Carlos Vives and Juan Garcia-Herreros, and the actors Catalina Sandino Moreno, John Leguizamo, Catherine Siachoque and Sofía Vergara.

The Colombian cuisine developed mainly from the food traditions of European countries. Spanish, Italian and French culinary influences can all be seen in Colombian cooking. The cuisine of neighboring Latin American countries, Mexico, the United States and the Caribbean, as well as the cooking traditions of the country's indigenous inhabitants, have all influenced Colombian food. For example, cuy or guinea pig, which is an indigenous cuisine, is eaten in the Andes region of south-western Colombia.

Many national symbols, both objects and themes, have arisen from Colombia's diverse cultural traditions and aim to represent what Colombia, and the Colombian people, have in common. Cultural expressions in Colombia are promoted by the government through the Ministry of Culture.

Popular culture[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The depiction of Colombia in popular culture, especially the portrayal of Colombian people in film and fiction, has been asserted by Colombian organizations[81][82][83] and government to be largely negative and has raised concerns that it reinforces, or even engenders, societal prejudice and discrimination due to association with narco-trafficking, terrorism and other criminal elements, and poverty.[84] These stereotypes are considered unfair by many Colombians.[85][86] The Colombian government funded the "Colombia es Pasión" advertisement campaign as an attempt to improve Colombia's image abroad, with mixed results.[87][88]

Cuisine[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

-

Sancocho de mondongo.

Colombia's cuisine, influenced heavily by the Spanish and Indigenous populations, is not as widely known as other Latin American cuisines such as Peruvian or Brazilian, but to the adventurous traveler there are plenty of delectable dishes to try, not to mention fruits, rum, and especially Colombian coffee.

See also[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- Index of Colombia-related articles

- National Library of Colombia

- United Nations Development Programme

- CIVETS

- South America Life Quality Rankings

Tham khảo[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- ^ Gerhar Sandner, Beate Ratter, Wolf Dietrich Sahr and Karsten Horsx (1993). “Conflictos Territoriales en el Mar Caribe: El conflicto fronterizo en el Golfo de Venezuela”. Biblioteca Luis Angel Arango (bằng tiếng Tây Ban Nha). Truy cập ngày 5 tháng 1 năm 2008.Quản lý CS1: nhiều tên: danh sách tác giả (liên kết)

- ^ The Geographer Office of the Geographer Bureau of Intelligence and Research (15 tháng 4 năm 1985). “Brazil-Colombia boundary” (PDF). International Boundary Study. Truy cập ngày 5 tháng 1 năm 2008.

- ^ CIA (13 tháng 12 năm 2007). “Ecuador”. World Fact Book. Truy cập ngày 5 tháng 1 năm 2008.

- ^ (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Tratados Internacionales limítrofes de Colombia

- ^ (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Colombia – Limites territoriales

- ^ Nicolás del Castillo Mathieu (1992). “La primera vision de las costas Colombianas, Repaso de Historia”. Revista Credencial (bằng tiếng Tây Ban Nha). Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 2 năm 2008. Đã bỏ qua tham số không rõ

|month=(trợ giúp) - ^ a b c d e f g h CIA world fact book (14 tháng 5 năm 2009). “Colombia”. CIA. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 5 năm 2009.

- ^ “Violence, Crime, and Illegal Arms Trafficking in Colombia” (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. tháng 11 năm 2006.

- ^ Mike Giglio (9 tháng 9 năm 2010). “Colombia Wrestling to Quell Local Drug Gangs”. Newsweek. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011.

- ^ “Gangs tied to paramilitaries cited in Colombia violence”. CNN. 3 tháng 2 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011.

- ^ McDermott, Jeremy (31 tháng 7 năm 2010). “Colombia sees crime rise in major cities”. BBC. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011.

- ^ “Verisk Maplecroft”. Truy cập 13 tháng 10 năm 2015.

- ^ “Colombia ranks 6 on terrorism risk list”. Colombia Reports. 15 tháng 11 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011.

- ^ David R. Davis, Brett Ashley Leeds and Will H. Moore (21 tháng 11 năm 1998). “Measuring Dissident and state behaviour: The Intranational Political Interactions (IPI) Project” (PDF). Florida State University. Truy cập ngày 5 tháng 1 năm 2008.

- ^ Jan Kippers Black (2005). Latin America, its problems and its promise: a multidisciplinary introduction. Westview Press. tr. 406. ISBN 9780813341644.

- ^ Stokes, Doug (2005). “America's Other War: Terrorizing Colombia”. Canadian Dimension. 39 (4): 26. Đã bỏ qua tham số không rõ

|month=(trợ giúp); Chú thích có tham số trống không rõ:|coauthors=(trợ giúp) - ^ Rudolf Hommes (22 de noviembre de 2009). “La otra seguridad democrática”. El Colombiano (bằng tiếng Tây Ban Nha). Kiểm tra giá trị ngày tháng trong:

|date=(trợ giúp) - ^ “OHCHR in Colombia (2008-2009)”. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 7 năm 2010.

- ^ “Almost Half of 43.7 Million Colombians Live Below the Poverty Line”. MercoPress. 4 tháng 5 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 7 năm 2010.

- ^ “¿Por qué Colombia no sale del club de los pobres?”. Revista Semana. 13 tháng 3 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 7 năm 2010.

- ^ “en Colombia Paisajes naturales de Colombia”. Telepolis.com. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ a b Carlos Restrepo Piedrahita (1992). “El nombre "Colombia", El único país que lleva el nombre del Descubrimiento”. Revista Credencial (bằng tiếng Tây Ban Nha). Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 2 năm 2008. Đã bỏ qua tham số không rõ

|month=(trợ giúp) - ^ “Tallest mountains by continent”. Mountainpeaks.net. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ “Human Development Report: Deforestation, 2007/2008”. Hdrstats.undp.org. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ “The World's Water”. Pacific Institute. 2008. tr. tables 1. Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 2 năm 2009.

- ^ “UNODC 2008 World Drug Report, Executive Summary” (PDF). Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ Van der Hammen, T. and Correal, G. 1978: "Prehistoric man on the Sabana de Bogotá: data for an ecological prehistory"; Paleography, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology 25:179–190

- ^ Broadbent, Sylvia 1965: Los Chibchas: organización socio-política. Série Latinoamericana 5. Bogotá: Facultad de Sociología, Universidad Nacional de Colombia

- ^ Simons, Geoff. Colombia: A Brutal History (London: Saqi, 2004), p. 19.

- ^ “The Story Of... Smallpox — and other Deadly Eurasian Germs”. Pbs.org. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ “Kidnapping on the rise for 1st time in decade”. Colombia Reports. 17 tháng 11 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011.

- ^ “Disminuir la tasa anual de homicidios por cada 100. 000 habitantes ( Sin accidentes de transito)” (bằng tiếng Tây Ban Nha). SIGOB. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 3 năm 2010.

- ^ “Homicidios 2002” (PDF) (bằng tiếng Tây Ban Nha). Medicina Legal. tr. 38, 42. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2009.[liên kết hỏng]

- ^ “Homicidios 2009” (PDF) (bằng tiếng Tây Ban Nha). Medicina Legal. tr. 30, 35–37, 65. Truy cập ngày 19 tháng 11 năm 2010.[liên kết hỏng]

- ^ “FARC, ELN have less than 10,000 members: government”. Colombia Reports. 24 tháng 7 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011.

- ^ Come to Sunny Colombia The Economist, June 29, 2006.

- ^ “Polo Democratico Alternativo ¿Por qué la parapolítica?” (bằng tiếng Tây Ban Nha). Polodemocratico.net. 26 tháng 2 năm 2007. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.[liên kết hỏng]

- ^ Colombian Constitution. 1991

- ^ “Portal del Estado Colombiano - Inicio”. Gobiernoenlinea.gov.co. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011.

- ^ [1][liên kết hỏng]

- ^ Bronstein, Hugh (6 tháng 7 năm 2008). “Reuters, Popularity of Colombia's Uribe soars after rescue”. Reuters.com. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ a b “Registraduria, Registraduria Nacional del Estado Civil”. Registraduria.gov.co. Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 6 năm 2010.

- ^ a b “Banco de la República, Economic and Financial Data for Colombia”. Banrep.gov.co. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ a b c d e “Human Development Report for Colombia, 2007/2008”. Hdrstats.undp.org. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ International Trade Centre: Colombia Exports[liên kết hỏng]

- ^ “International Colored Gemstone Association: Emerald”. Gemstone.org. 28 tháng 9 năm 2001. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 21 tháng 8 năm 2008. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ America's Flower Basket: Colombian Flowers and the American Marketplace[liên kết hỏng]

- ^ “Heritage Foundation, Index of Economic Freedom”. Heritage.org. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ BusinessWeek, Colombia, The Most Extreme Emerging Market on Earth May 28, 2007

- ^ The Economist, Colombia's resilient economy, October 17, 2009

- ^ “Doing Business in Colombia”. Doingbusiness.org. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ By Marián Hens (7 tháng 12 năm 2007). “BBC News, A new hot-spot for the tourism industry”. BBC News. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ “Hot Destination: Colombia”. Christian Science Monitor. 9 tháng 5 năm 2006.

- ^ El Espectador (spanish) http://elespectador.com/noticias/bogota/articulo-269115-bogota-ocupa-sexto-puesto-america-latina-ranking-de-turismo

- ^ 'Travel Warning: Colombia' U.S. State Department, 2010

- ^ Infraero.gov.br[liên kết hỏng]

- ^ “China in talks over Panama Canal rival”. Ft.com. 13 tháng 2 năm 2011. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011.

- ^ “Colombia: A Country Study”. Countrystudies.us. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ “Colombia has most displaced in world: UN”. Colombia Reports. 9 tháng 11 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011.

- ^ Number of internally displaced people remains stable at 26 million. Source: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). May 4, 2009.

- ^ “Colombia una nación multicultural: su diversidad étnica” (PDF). Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011.

- ^ “Comunidades Negras: Poblacion Negra Afrocolombiana”. Todacolombia.com. 28 tháng 3 năm 2007. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 11 năm 2010.

- ^ “The Languages of Colombia”. Ethnologue.com. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ EPM (2005). “La etnia Wayuu”. Empresas Publicas de Medellín (bằng tiếng Tây Ban Nha). Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 19 tháng 2 năm 2008. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 2 năm 2008.

- ^ “Los Resguardos Indígenas”. Etniasdecolombia.org. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 5 năm 2011.

- ^ EPM (2005). “La etnia Wayuu”. Empresas Publicas de Medellín (bằng tiếng Tây Ban Nha). Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 19 tháng 2 năm 2008. Truy cập ngày 29 tháng 2 năm 2008.

- ^ “ILOLEX: submits English query”. Ilo.org. 9 tháng 1 năm 2004. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Colombia una Los grupos étnicos colombianos

- ^ Colombia, Opinion survey 2009, by ICRC and Ipsos

- ^ “Colombia in Crisis”. Jon Lottman, Center for Defense Information. Truy cập ngày 8 tháng 9 năm 2010.

- ^ International Trade Union Confederation, 11 June 2010, ITUC responds to the press release issued by the Colombian Interior Ministry concerning its survey

- ^ “Religious Intelligence — Country Profile: Colombia”. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 27 tháng 9 năm 2007. Truy cập ngày 3 tháng 10 năm 2007.

- ^ a b International Religious Freedom Report 2005, by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State, November 8, 2005.

- ^ Constitution of Colombia, 1991 (Article 19)

- ^ Colombia country profile. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (February 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Artículo 67, Constitución Política de Colombia

- ^ Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos: Sistemas Educativos Nacionales, Colombia, OEI.es

- ^ “Ministerio de Educación de Colombia, Estructura del sistema educativo”. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ a b c “UNESCO Institute for Statistics Colombia Profile”. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ “US Department of State Background Note: Colombia”. State.gov. 24 tháng 2 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 5 năm 2010.

- ^ Fohr, D. Mythes et rélatéis del'Amérique Latine a travers le dépliantpublicitaire touristique. Thásedu 3ecy-de, Université de París III, 1981.

- ^ Bouroon, J. "Les étrangers au primetime ou, la télévision est-elle xénophobe? Télévision d'Europe et Immigration. INA et Association Dialogue entre cultures, 1993

- ^ Marketing internacional de lugares y destinos: estrategias para la atracción de clientes y negocios en Latinoamérica. Authors: Philip Kotler, Víctor Campos Olguín, Matthew G. Whitehouse. Editor Pearson Educación, 2 hotdog 007. ISBN 970-26-0852-X, 9789702608523

- ^ AC Zentella. "'José, can you see?': Latino Responses to Racist Discourse.". Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- ^ (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Rodriguez, P. Estereotipos denacionalidad en estudiantes colombianos y venezolanos. Boletín de la VEPSO,Vol. XV, Nos. 1–3,65–74,1992

- ^ Wetherell, M. «Cross-culturalstudies ofminimal groups: implicationsfor the social identity theory of inter-group relations», 1982. Tajfel, H. Social identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge University Press, 1982

- ^ Tiempoviajes.com[liên kết hỏng]

- ^ Jenkins, Simon (2 tháng 2 năm 2007). “Passion alone won't rescue Colombia from its narco-economy stigma”. The Guardian. London. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 4 năm 2010.

Further reading[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- (English) Mellander, Gustavo A.; Nelly Maldonado Mellander (1999). Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1-56328-155-4. OCLC 42970390.

- (English) Mellander, Gustavo A. (1971). The United States in Panamanian Politics: The Intriguing Formative Years. Danville, Ill.: Interstate Publishers. OCLC 138568.

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Academia Colombiana de Historia (1986), Historia extensa de Colombia (41 volumes). Bogotá: Ediciones Lerner, 1965–1986. ISBN 958-95013-3-8 (Complete work)

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Barrios, Luis (1984), Historia de Colombia. Fifth edition, Bogotá: Editorial Cultural

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Bedoya F., Víctor A. (1944), Historia de Colombia: independencia y república con bases fundamentales en la colonia. Colección La Salle, Bogotá: Librería Stella

- Bushnell, David (1993), The Making of Modern Colombia: A Nation in Spite of Itself. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08289-3

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Caballero Argaez, Carlos (1987), 50 años de economía: de la crisis del treinta à la del ochenta. Second edition, Colección Jorge Ortega Torres, Bogotá: Editorial Presencia, Asociación Bancaria de Colombia. ISBN 958-9040-03-9

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Cadavid Misas, Roberto (2004), Cursillo de historia de Colombia: de la conquista à la independencia. Bogotá: Intermedio Editores. ISBN 958-709-134-5

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Calderón Schrader, Camilo; Gil, Antonio; Torras, Daniel (2001), Enciclopedia de Colombia (4 volumes). Barcelona: Céano Grupo Editorial, 2001. ISBN 84-494-1947-6 (Complete work)

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Calderón Schrader, Camilo (1993), Gran enciclopedia de Colombia (11 volumes). Bogotá: Círculo de Lectores. ISBN 958-28-0294-4 (Complete work)

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Cavelier Gaviria, Germán (2003), Centenario de Panamá: una historia de la separación de Colombia en 1903. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia. ISBN 958-616-718-6

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Forero, Manuel José (1946), Historia analítica de Colombia desde los orígenes de la independencia nacional. Second edition, Bogotá: Librería Voluntad.

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Gómez Hoyos, Rafael (1992), La independencia de Colombia. Madrid: Editorial Mapfre, Colecciones Mapfre 1492. ISBN 84-7100-596-4

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Granados, Rafael María (1978), Historia general de Colombia: prehistoria, conquista, colonia, independencia y Repúbica. Eighth edition, Bogotá: Imprenta Departamental Antonio Nariño.

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Hernández de Alba, Guillermo (2004), Como nació la República de Colombia. Colección Bolsilibros. Bogotá: Academia Colombiana de Historia. ISBN 958-8040-35-3

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Hernández Becerra, Augusto (2001), Ordenamiento y desarreglo territorial en Colombia. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia, ISBN 958-616-555-8

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Hernández Rodríguez, Guillermo (1949), De los chibchas à la colonia y à la república. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Sección de Extensión Cultural.

- Hylton, Forrest (2006), Evil Hour in Colombia. New York: Verso Books. ISBN 1-84467-551-3

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Jaramillo Uribe, Jaime; Tirado Mejía, Álvaro; Calderón Schrader, Camilo (2000), Nueva historia de Colombia (12 volumes). Bogotá: Planeta Colombiana Editorial. ISBN 958-614-251-5 (Complete work)

- Kirk, Robin (2004), More Terrible Than Death: Drugs, Violence, and America's War in Colombia. United States: PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-58648-207-6

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Ocampo López, Javier (1999), El proceso ideológico de la emancipación en Colombia. Colección La Línea de Horizonte, Bogotá: Editorial Planeta. ISBN 958-614-792-4

- Ospina, William (2006), Once Upon a Time There Was Colombia. Colombia: Villegas Asociados. ISBN 958-8156-64-5

- Palacios, Marco (2006), Between Legitimacy and Violence: A History of Colombia, 1875–2002. United States of America: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3767-3

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo (1998), Colombia indígena. Medellín: Hola Colina. ISBN 958-638-276-1

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Restrepo, José Manuel (1974), Historia de la revolución de la República de Colombia. Medellín: Editorial Bedout.

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Rivadeneira Vargas, Antonio José (2002), Historia constitucional de Colombia 1510–2000. Third edition, Tunja: Editorial Bolivariana Internacional.

- Simons, Geoff (2004), Colombia: A Brutal History. London: Saqi Books. ISBN 0-86356-758-4

- Smith, Stephen (1999), Cocaine Train: Travels in Colombia. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-64749-7

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Tovar Pinzón, Hermes (1975), El movimiento campesino en Colombia durante los siglos XIX y XX. Second edition, Bogotá: Ediciones Libres.

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Trujillo Muñoz Augusto (2001), Descentralización, regionalización y autonomía local. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Vidal Perdomo Jaime (2001), La Región en la Organización Territorial del Estado. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario.

Liên kết ngoài[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

| Từ điển từ Wiktionary | |

| Tập tin phương tiện từ Commons | |

| Tin tức từ Wikinews | |

| Danh ngôn từ Wikiquote | |

| Văn kiện từ Wikisource | |

| Tủ sách giáo khoa từ Wikibooks | |

| Tài nguyên học tập từ Wikiversity | |

| Wikivoyage có cẩm nang du lịch về Colombia. |

- Colombia Travel – Colombia: Official Tourism Portal (tiếng Anh)

- Colombia Investment – Colombia: Official Investment Portall (tiếng Anh)

- Portal del Estado – Colombia Online Government web site (tiếng Tây Ban Nha)

- Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi – Maps of Colombia (tiếng Tây Ban Nha)

- Colombia at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Mục “Colombia” trên trang của CIA World Factbook.

- News on Colombia in English

- Colombia History Geography and Culture

- Colombia at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Guest001/translated colombia article trên DMOZ

- Witness for Peace: Colombia Program

- Satellital view of all cities of Colombia

- Mexican Decree recognizing the National sovereignty of Colombia as a free and independent power, 2 May 1822

- The Colombia Report - informative articles in English

- UNDP.org

- Colombia: a top emerging country - Official investment portal report

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadistica – National Administrative Department of Statistics (tiếng Tây Ban Nha)

- The ICRC in Colombia

Related information[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Bản mẫu:Colombia topics Bản mẫu:Symbols of Colombia [[Thể loại:Member states of the Union of South American N