Khác biệt giữa bản sửa đổi của “Iridi”

→Sản xuất: tạm ngưng |

|||

| Dòng 136: | Dòng 136: | ||

| accessdate = 2014-01-10}} |

| accessdate = 2014-01-10}} |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

==Ứng dụng== |

|||

Nhu cầu iridi dao động trong khoảng từ 2,5 tấn năm 2009 đến 10,4 năm 2010, hầu hết là các ứng dụng liên quan đến điện tử làm tăng từ 0,2 đến 6 tấn – các nồi nấu kim loại iridi được sử dụng phổ biến để nuôi các tinh thế đơn lẻ chất lượng cao, làm cho nhu cầu tăng mạnh. Việc tăng lượng tiêu thụ iridi được dự đoán đạt bảo hòa vì được dồn vào các lò nấu kim loại, như đã diễn ra trước đây torng thập niên 2000. Các ứng dụng chính khác như làm bugi đánh lửa tiêu thụ 0,78 tấn iridi năm 2007, điện cực trong [[công nghệ chloralkali]] (1,1 tấn năm 2007) và xúc tác hóa học (0,75 năm 2007).<ref name=usgs/><ref name="platinum2008">{{cite book| first = D.| last = Jollie| title=Platinum 2008|publisher=Johnson Matthey|date=2008| issn = 0268-7305|url=http://www.platinum.matthey.com/uploaded_files/Pt2008/08_complete_publication.pdf| format = PDF|accessdate=2008-10-13}}</ref> |

|||

===Trong công nghiệp và y học=== |

|||

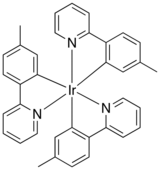

[[File:Ir(mppy)3.png|thumb|160px|right|Cấu trúc phân tử của {{chem|Ir(mppy)|3}}|alt=Khung của hợp chất hóa học với nguyên tử iridi ở giữa, liên kết với 6 vòng benzens. Các vòng này nối cặp với nhau.]] |

|||

Tính chống mòn, độ cứng và nóng chảy cao của iridi và các kim loại của nó định hình nên hầu hết các ứng dụng của chúng. Iridi và đặc biệt là hợp kim iridi-platin hoặc iridi-osmi có a low wear và được sử dụng, ví dụ for multi-pored [[Spinneret (polymers)|spinnerets]], qua đó polymer plastic tan chảy được đẩy ra tạo thành các sợi như [[rayon]].<ref>{{cite journal|title= Spinnerets for viscose rayon cord yarn| journal = Fibre Chemistry| volume =10| issue = 4| date = 1979| doi = 10.1007/BF00543390| pages = 377–378| first = R. V.| last = Egorova|author2=Korotkov, B. V. |author3=Yaroshchuk, E. G. |author4=Mirkus, K. A. |author5=Dorofeev N. A. |author6= Serkov, A. T. }}</ref> Osmi–iridi được dùng làm vòng la bàn và để giữa thăng bằng.<ref name="Emsley2">{{cite web| url = http://www.rsc.org/chemsoc/visualelements//PAGES/pdf/iridium.PDF| title = Iridium|publisher = Royal Society of Chemistry| work = Visual Elements Periodic Table| format = PDF| author = Emsley, J.| date = 2005-01-18| accessdate = 2008-09-17}}</ref> |

|||

{{Đang dịch 2 (nguồn)|ngày=5 |

|||

|tháng=02 |

|||

|năm=2017 |

|||

|1 = |

|||

}} |

|||

Their resistance to arc erosion makes iridium alloys ideal for electrical contacts for [[spark plug]]s,<ref name="Handley" /><ref>{{cite book| url = https://books.google.com/?id=I03qepnj2IwC| title = Euromat 99| author = Stallforth, H.| author2 = Revell, P. A.| publisher= Wiley-VCH| date = 2000| isbn = 978-3-527-30124-9}}</ref> and iridium-based spark plugs are particularly used in aviation. |

|||

Pure iridium is extremely brittle, to the point of being hard to weld because the heat-affected zone cracks, but it can be made more ductile by addition of small quantities of [[titanium]] and [[zirconium]] (0.2% of each apparently works well)<ref>{{cite patent|country=US |number=3293031A|invent1=Cresswell, Peter|invent2=Rhys, David|pridate=23/12/1963|fdate=27/11/1964|pubdate=20/12/1966}}</ref> |

|||

Corrosion and heat resistance makes iridium an important alloying agent. Certain long-life aircraft engine parts are made of an iridium alloy, and an iridium–[[titanium]] alloy is used for deep-water pipes because of its corrosion resistance.<ref name="Emsley"/> Iridium is also used as a hardening agent in platinum alloys. The [[Vickers hardness]] of pure platinum is 56 HV, whereas platinum with 50% of iridium can reach over 500 HV.<ref>{{cite journal| url = http://www.platinummetalsreview.com/pdf/pmr-v4-i1-018-026.pdf|format=PDF|accessdate=2008-10-13| journal = Platinum Metals Review| title = Iridium Platinum Alloys| first = A. S.|last = Darling| date = 1960| volume =4| issue =l| pages = 18–26}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|doi = 10.1595/147106705X24409| title = The Hardening of Platinum Alloys for Potential Jewellery Application| first = T.|last = Biggs| author2=Taylor, S. S.| author3=van der Lingen, E.| journal = Platinum Metals Review| date = 2005| volume = 49| issue = 1| pages = 2–15}}</ref> |

|||

Devices that must withstand extremely high temperatures are often made from iridium. For example, high-temperature [[crucible]]s made of iridium are used in the [[Czochralski process]] to produce oxide single-crystals (such as [[sapphire]]s) for use in computer memory devices and in solid state lasers.<ref name="Handley">{{cite journal|title= Increasing Applications for Iridium| first = J. R.| last = Handley| journal = Platinum Metals Review| volume = 30| issue = 1| date = 1986| pages = 12–13| url = http://www.platinummetalsreview.com/pdf/pmr-v30-i1-012-013.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title= On the Use of Iridium Crucibles in Chemical Operations| first = W.| last = Crookes|authorlink=William Crookes| journal = Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character| volume = 80| issue = 541| date = 1908| pages = 535–536| jstor = 93031|doi= 10.1098/rspa.1908.0046|bibcode = 1908RSPSA..80..535C }}</ref> The crystals, such as [[gadolinium gallium garnet]] and yttrium gallium garnet, are grown by melting pre-sintered charges of mixed oxides under oxidizing conditions at temperatures up to 2100 °C.<ref name="hunt" /> |

|||

Iridium compounds are used as [[catalysis|catalysts]] in the [[Cativa process]] for [[carbonylation]] of [[methanol]] to produce [[acetic acid]].<ref name="ullmann-acetic">{{cite book|first=H.|last= Cheung| author2=Tanke, R. S.| author3=Torrence, G. P.|chapter=Acetic acid|title=Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry|publisher=Wiley|date=2000|doi=10.1002/14356007.a01_045}}</ref> |

|||

The radioisotope [[iridium-192]] is one of the two most important sources of energy for use in industrial [[Industrial radiography#Radioisotope sources|γ-radiography]] for [[non-destructive testing]] of [[metal]]s.<ref>{{cite journal|title= The use and scope of Iridium 192 for the radiography of steel| first = R.| last = Halmshaw| date = 1954| journal = British Journal of Applied Physics| volume = 5| pages = 238–243| doi = 10.1088/0508-3443/5/7/302|bibcode = 1954BJAP....5..238H|issue= 7 }}</ref><ref name=Hellier>{{cite book|last = Hellier|first = Chuck|title = Handbook of Nondestructive Evlaluation|publisher = The McGraw-Hill Companies|date = 2001|isbn = 978-0-07-028121-9}}</ref> Additionally, <sup>192</sup>Ir is used as a source of [[gamma radiation]] for the treatment of cancer using [[brachytherapy]], a form of radiotherapy where a sealed radioactive source is placed inside or next to the area requiring treatment. Specific treatments include high-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy, bilary duct brachytherapy, and intracavitary cervix brachytherapy.<ref name="Emsley" /> |

|||

Iridium is a good catalyst for the decomposition of [[hydrazine]] (into hot nitrogen and ammonia), and this is used in practice in low-thrust rocket engines; there are more details in the [[monopropellant rocket]] article. |

|||

===Trong khoa học=== |

|||

[[File:Platinum-Iridium meter bar.jpg|right|thumb|[[International Prototype Metre]] bar|alt=NIST Library US Prototype meter bar]] |

|||

An alloy of 90% platinum and 10% iridium was used in 1889 to construct the [[International Prototype Metre]] and [[Kilogram#International prototype kilogram|kilogram]] mass, kept by the [[Bureau International des Poids et Mesures|International Bureau of Weights and Measures]] near [[Paris]].<ref name="Emsley" /> The meter bar was replaced as the definition of the fundamental unit of length in 1960 by a line in the [[atomic spectrum]] of [[Krypton#Metric role|krypton]],<ref group="note">The definition of the meter was changed again in 1983. The meter is currently defined as the distance traveled by light in a vacuum during a time interval of {{frac|299,792,458}} of a second.</ref><ref name="meter">{{cite web| url=http://www.mel.nist.gov/div821/museum/timeline.htm| publisher = National Institute for Standards and Technology|first =W. B.| last = Penzes|title=Time Line for the Definition of the Meter|date=2001|accessdate=2008-09-16}}</ref> but the kilogram prototype is still the international standard of mass.<ref>General section citations: ''Recalibration of the U.S. National Prototype Kilogram'', R.{{nbsp}}S.{{nbsp}}Davis, Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards, '''90''', No. 4, {{nowrap|July–August}} 1985 ([http://nvl.nist.gov/pub/nistpubs/jres/090/4/V90-4.pdf 5.5{{nbsp}}MB PDF, here]); and ''The Kilogram and Measurements of Mass and Force'', Z.{{nbsp}}J.{{nbsp}}Jabbour ''et al.'', J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. '''106''', 2001, {{nowrap|25–46}} ([http://nvl.nist.gov/pub/nistpubs/jres/106/1/j61jab.pdf 3.5{{nbsp}}MB PDF, here])<sub>{{nbsp}}</sub></ref> |

|||

Iridium has been used in the [[radioisotope thermoelectric generator]]s of unmanned spacecraft such as the ''[[Voyager program|Voyager]]'', ''[[Viking program|Viking]]'', ''[[Pioneer program|Pioneer]]'', ''[[Cassini-Huygens|Cassini]]'', ''[[Galileo (spacecraft)|Galileo]]'', and ''[[New Horizons]]''. Iridium was chosen to encapsulate the [[plutonium-238]] fuel in the generator because it can withstand the operating temperatures of up to 2000 °C and for its great strength.<ref name="hunt" /> |

|||

Another use concerns X-ray optics, especially X-ray telescopes.<ref name="Ziegler">{{cite journal| doi = 10.1016/S0168-9002(01)00533-2| title = High-efficiency tunable X-ray focusing optics using mirrors and laterally-graded multilayers| first = E.| last = Ziegler| author2=Hignette, O.| author3=Morawe, Ch.| author4=Tucoulou, R.| journal = Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment| volume = 467–468| date = 2001|pages = 954–957|bibcode = 2001NIMPA.467..954Z }}</ref> The mirrors of the [[Chandra X-ray Observatory]] are coated with a layer of iridium 60 [[nanometer|nm]] thick. Iridium proved to be the best choice for reflecting X-rays after nickel, gold, and platinum were also tested. The iridium layer, which had to be smooth to within a few atoms, was applied by depositing iridium vapor under [[vacuum|high vacuum]] on a base layer of [[chromium]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Face-to-Face with Jerry Johnston, CXC Program Manager & Bob Hahn, Chief Engineer at Optical Coating Laboratories, Inc., Santa Rosa, CA|publisher=Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics; Chandra X-ray Center|url=http://chandra.harvard.edu/press/bios/johnston.html|accessdate=2008-09-24|date=1995}}</ref> |

|||

Iridium is used in [[particle physics]] for the production of [[antiproton]]s, a form of [[antimatter]]. Antiprotons are made by shooting a high-intensity proton beam at a ''conversion target'', which needs to be made from a very high density material. Although [[tungsten]] may be used instead, iridium has the advantage of better stability under the [[shock wave]]s induced by the temperature rise due to the incident beam.<ref>{{cite journal|title = Production of low-energy antiprotons| journal =Zeitschrift Hyperfine Interactions| volume =109| date = 1997|doi = 10.1023/A:1012680728257| pages = 33–41| first = D.| last =Möhl|bibcode = 1997HyInt.109...33M }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:C-HactnBergGrah.png|450px|left|thumb|Oxidative addition to hydrocarbons in [[organoiridium chemistry]]<ref name=RGB>{{cite journal|title=Carbon-hydrogen activation in completely saturated hydrocarbons: direct observation of M + R-H -> M(R)(H)|author=Janowicz, A. H.|author2=Bergman, R. G.|journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society|date=1982|volume=104|issue=1|pages=352–354|doi=10.1021/ja00365a091}}</ref><ref name=WAGG>{{cite journal|title=Oxidative addition of the carbon-hydrogen bonds of neopentane and cyclohexane to a photochemically generated iridium(I) complex|author=Hoyano, J. K.|author2=Graham, W. A. G.|journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society|date=1982|volume=104|issue=13|pages=3723–3725|doi=10.1021/ja00377a032}}</ref>|alt=Skeletal formula presentation of a chemical transformation. The initial compounds have a C5H5 ring on their top and an iridium atom in the center, which is bonded to two hydrogen atoms and a P-PH3 group or to two C-O groups. Reaction with alkane under UV light alters those groups.]] |

|||

[[C-H bond activation|Carbon–hydrogen bond activation]] (C–H activation) is an area of research on reactions that cleave [[carbon–hydrogen bond]]s, which were traditionally regarded as unreactive. The first reported successes at activating C–H bonds in [[saturated hydrocarbon]]s, published in 1982, used organometallic iridium complexes that undergo an [[oxidative addition]] with the hydrocarbon.<ref name=RGB/><ref name=WAGG/> |

|||

Iridium complexes are being investigated as catalysts for [[asymmetric hydrogenation]]. These catalysts have been used in the synthesis of [[natural product]]s and able to hydrogenate certain difficult substrates, such as unfunctionalized alkenes, enantioselectively (generating only one of the two possible [[enantiomer]]s).<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1002/chem.200500755|date=2006|author=Källström, K|author2=Munslow, I|author3=Andersson, P. G.|title=Ir-catalysed asymmetric hydrogenation: Ligands, substrates and mechanism|volume=12|issue=12|pages=3194–3200|pmid=16304642|journal=Chemistry: A European Journal}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1021/ar700113g|date=2007|author=Roseblade, S. J.|author2=Pfaltz, A.|title=Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of olefins|volume=40|issue=12|pages=1402–1411|pmid=17672517|journal=[[Accounts of Chemical Research]]}}</ref> |

|||

Iridium forms a variety of [[Complex (chemistry)|complexes]] of fundamental interest in triplet harvesting.<ref>{{cite journal|title = Electrophosphorescence from substituted poly(thiophene) doped with iridium or platinum complex| doi = 10.1016/j.tsf.2004.05.095| date = 2004| journal = Thin Solid Films| volume = 468| issue = 1–2| pages = 226–233| first = X.| last = Wang| author2=Andersson, M. R.| author3=Thompson, M. E.| author4=Inganäsa, O.|bibcode = 2004TSF...468..226W }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|url=http://sa.rochester.edu/jur/issues/fall2002/tonzetich.pdf|title=Organic Light Emitting Diodes—Developing Chemicals to Light the Future|publisher=Rochester University|first=Zachary J.|last=Tonzetich|journal=Journal of Undergraduate Research|volume=1|issue=1|date=2002|format=PDF|accessdate=2008-10-10}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal| title=New Trends in the Use of Transition Metal-Ligand Complexes for Applications in Electroluminescent Devices| author = Holder, E.| author2=Langefeld, B. M. W.| author3=Schubert, U. S.| journal = Advanced Materials| volume = 17| issue = 9| pages = 1109–1121| date = 2005-04-25|doi=10.1002/adma.200400284}}</ref> |

|||

===Trong nghiên cứu lịch sử=== |

|||

[[File:Gama Supreme Flat Top ebonite eyedropper fountain pen 3.JPG|right|thumb|[[Fountain pen]] nib labeled ''Iridium Point'']] |

|||

Iridium–osmium alloys were used in [[fountain pen]] [[Nib_(pen)#Nib_tipping|nib tip]]s. The first major use of iridium was in 1834 in nibs mounted on gold.<ref name="hunt" /> Since 1944, the famous [[Parker 51]] fountain pen was fitted with a nib tipped by a ruthenium and iridium alloy (with 3.8% iridium). The tip material in modern fountain pens is still conventionally called "iridium", although there is seldom any iridium in it; other metals such as ruthenium, osmium and tungsten have taken its place.<ref>{{cite journal|url=http://www.nibs.com/ArticleIndex.html|journal=The PENnant|volume=XIII|issue=2|date=1999|title=Notes from the Nib Works—Where's the Iridium?|author=Mottishaw, J.}}</ref> |

|||

An iridium–platinum alloy was used for the [[touch hole]]s or vent pieces of [[cannon]]. According to a report of the [[Exposition Universelle (1867)|Paris Exhibition of 1867]], one of the pieces being exhibited by [[Johnson and Matthey]] "has been used in a Withworth gun for more than 3000 rounds, and scarcely shows signs of wear yet. Those who know the constant trouble and expense which are occasioned by the wearing of the vent-pieces of cannon when in active service, will appreciate this important adaptation".<ref>{{cite journal|editor=Crookes, W.|volume=XV|date=1867|journal=The Chemical News and Journal of Physical Science|title=The Paris Exhibition|pages=182 }}</ref> |

|||

The pigment ''iridium black'', which consists of very finely divided iridium, is used for painting [[porcelain]] an intense black; it was said that "all other porcelain black colors appear grey by the side of it".<ref>{{cite book|title=The Playbook of Metals: Including Personal Narratives of Visits to Coal, Lead, Copper, and Tin Mines, with a Large Number of Interesting Experiments Relating to Alchemy and the Chemistry of the Fifty Metallic Elements|author=Pepper, J. H.|publisher=Routledge, Warne, and Routledge|date=1861|page=455}}</ref> |

|||

==Ứng dụng== |

==Ứng dụng== |

||

Phiên bản lúc 14:56, ngày 5 tháng 2 năm 2017

Bản mẫu:Iridi Iridi là một nguyên tố hóa học với số nguyên tử 77 và kí hiệu là Ir. Là một kim loại chuyển tiếp, cứng, màu trắng bạc thuộc nhóm platin, iridi là nguyên tố đặc thứ 2 (sau osmi) và là kim loại có khả năng chống ăn mòn nhất, thậm chí ở nhiệt độ cao khoảng 2000 °C. Mặc dù chỉ các muối nóng chảy và halogen nhất định mới ăn mòn iridi rắn, bụi iridi mịn thì phản ứng mạnh hơn và thậm chí có thể cháy. Các hợp chất iridi quan trọng nhất được sử dụng là các muối và axit tạo thành với clo, mặc dù iridi cũng tạo thành một số các hợp chất kim loại hữu cơ được dùng làm chất xúc tác và nghiên cứu.191Ir và 193Ir là hai đồng vị tự nhiên của iridi và cũng là hai đồng vị bền; trong đó đồng vị 193Ir phổ biến hơn.

Iridi được Smithson Tennant phát hiện năm 1803 ở Luân Đôn, Anh, trong số các tạp chất không hòa tan trong platin tự nhiên ở Nam Mỹ. Mặc dù nó là một trong những nguyên tố hiếm nhất trong vỏ Trái Đất, với sản lượng và tiêu thụ hàng năm chỉ 3 tấn, nó có nhiều ứng dụng trong công nghiệp đặc thù và trong khoa học. Iridi được dùng với chức năng chống ăn mòn cao ở nhiệt độ cao như nồi nung làm tái kết tinh của các chất bán dẫn ở nhiệt độ cao, các điện cực trong sản xuất clo, và máy phát nhiệt điện đồng vị phóng xạ được dùng trong phi thuyền không người lái. Các hợp chất iridi cũng được dùng làm các chất xúc tác trong sản xuất axit axetic. Trong công nghiệp ôtô, iridi được dùng làm bugi đánh lửa (high-end after-market sparkplugs) với vai trò điện cực trung tâm, thay thế việc sử dụng các kim loại thông thường.

Các dị thường iridi cao trong lớp sét thuộc ranh giới địa chất K-T (kỷ Creta-kỷ Trias) đã đưa đến giả thuyết Alvarez, mà theo đó sự ảnh hưởng của một vật thể lớn ngoài không gian đã gây ra sự tiệt chủng của khủng long và các loài khác cách đây 65 triệu năm. Iridi được tìm thấy trong các thiên thạch với hàm lượng cao hơn hàm lượng trung bình trong vỏ Trái Đất. Người ta cho rằng lượng iridi trong Trái Đất cao hơn hàm lượng được tìm thấy trong lớp vỏ đá của nó, nhưng có mật độ cao và khuynh hướng của iridi liên kết với sắt, hầu hết iridi giảm theo chiều từ bên dưới lớp vỏ đi vào tâm Trái Đất khi Trái Đất còn trẻ và vẫn nóng chảy.

Iridi có thể được làm thành dải hoặc dây mảnh bằng cách cán hoặc chuốt kéo.

Tính chất

Tính chất vật lý

Là thành viên của các kim loại nhóm platin, iridi có màu trắng tương tự platin nhưng chơi ngả sang màu vàng nhạt. Do độ cứng, giòn, và điểm nóng chảy rất cao của nó, iridi rắn khó gia công, định hình, và thường được sử dụng ở dạng bột luyện kim.[1] Nó là kim loại duy nhất duy trì được các đặc điểm cơ học tốt trong không khí ở nhiệt độ trên 1600 °C.[2] Iridi có điểm nóng chảy cao và trở thành chất siêu dẫn ở nhiệt độ dưới 0,14 K.[3]

Mô đun đàn hồi của iridi lớn thứ 2 trong các kim loại, sau osmi.[2] Điều này kết hợp với mô đun độ cứng cao và hệ số Poisson thấp cho thấy cấp độ của độ cứng và khả năng chống biến dạng lớn nên để chế tạo các bộ phận hữu ích là vấn đề rất khó khăn. Mặc dù có những hạn chế và giá cao, nhiều ứng dụng đã được triển khai trong các môi trường cần độ bền cơ học cao đặc biệt trong công nghệ hiện đại.[2]

Mật độ được đo đạc của iridi chỉ thấp hơn của osmi một ít (khoảng 0,1%).[4][5] Có một số nhập nhằng liên quan đến hai nguyên tố này là nguyên tố nào đặc hơn, do kích thước nhỏ khác nhau về mật độ và khó khăn về độ chính xác của phép đo,[6] nhưng, khi độ chính xác tăng khi tính mật độ bằng dữ liệu tinh thể học tia X thì mật độ của iridi là 22,56 g/cm3 và của osmi là 22,59 g/cm3.[7]

Tính chất hóa học

Iridi là kim loại có khả năng chống ăn mòn lớn nhất:[8] nó không phản ứng với hầu hết axit, nước cường toan, kim loại nóng chảy hay các silicat ở nhiệt độ cao. Tuy nhiên, nó có thể phản ứng với một số muối nóng chảy như natri xyanua và kali xyanua,[8] cũng như oxy và các halogen (đặc biệt flo)[9] ở nhiệt độ cao hơn.[10]

Các hợp chất

| Các trạng thái ôxy hóa[note 1] | |

|---|---|

| −3 | [Ir(CO) 3]3− |

| −1 | [Ir(CO) 3(PPh)] 3 |

| 0 | Ir 4(CO) 12 |

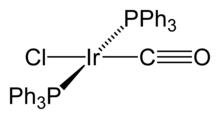

| +1 | [Ir(CO)Cl(PPh 3) 2] |

| +2 | IrCl 2 |

| +3 | IrCl 3 |

| +4 | IrO 2 |

| +5 | Ir 4F 20 |

| +6 | IrF 6 |

Iridi tạo thành các hợp chất ở dạng ôxit có trạng thái ôxi hóa từ −3 đến +6; trạng thái ôxy hóa phổ biến nhất là +3 và +4.[1] Các mẫu có tính chất đặc trưng tốt của các trạng thái ôxy hóa cao nhất thì hiếm có, nhưng có một số dạng như IrF

6 và 2 ôxit hỗn hợp Sr

2MgIrO

6 và Sr

2CaIrO

6.[1][11] Ngoài ra, năm 2009, iridi(VIII) tetroxit (IrO

4) đã được điều chế ở dạng matrix isolation conditions (6 K trong Ar) bằng cách chiếu tia cực tím vào phức iridium-peroxo. Tuy nhiên, mẫu này không ổn định như mong đợi khi mà trạng thái rắn của nó phải được duy trì ở nhiệt độ cao hơn.[12] Trạng thái ôxy hóa cao nhất (+9) cũng là điểm mà nhiệt độ cao nhất được ghi nhận đối với bất kỳ nguyên tố này, chỉ được biết đến ở một cation IrO+

4; đó là loại pha khí duy nhất được biết đến và không hình thành bất kỳ muối nào.[13]

Iridi điôxít, IrO

2, một chất bột màu nâu, là ôxít của iridi được mô tả chi tiết nhất.[1] Sesquioxit, Ir

2O

3, đã được mô tả là một chất bộ màu xanh-đen bị ô-xy hóa thành IrO

2 bởi HNO

3.[9] Disulfua, diselenua, sesquisulfua, và sesquiselenua tương ứng cũng đã được biết đến, và IrS

3 cũng đã được nghiên cứu.[1] Iridi cũng tạo thành các iridat có trạng thái ô-xy hóa +4 và +5, như K

2IrO

3 và KIrO

3, các chất này có thể được điều chế từ phản ứng của kali ô-xít hoặc kali superoxit với iridi ở nhiệt độ cao.[14]

Mặc dù các hydrua hai cấu tử của iridi, Ir

xH

y đã được biết đến, các phức được cho là có chứa IrH4−

5 và IrH3−

6, trong các phức này iridi có trạng thái ô-xy hóa tương ứng là +1 và +3.[15] Hydrua ba cấu tử Mg

6Ir

2H

11 được tin là chứa cả IrH4−

5 và IrH5−

4 18-electron.[16]

Không monohalua hoặc dihalua nào tồn tại trong khi trihalua, IrX

3, kết hợp với tất cả halogen.[1] Đối với trạng thái ô-xy hóa +4 và cao hơn, chỉ có tetrafluorua, pentafluorua và hexafluorua là tồn tại.[1] Iridi hexafluorua, IrF

6, là chất rắn màu vàng có tính phản ứng mạnh, bao gồm các phân tử tám mặt. Nó phân hủy trong nước và bị khử thành IrF

4, chất rắn kết tinh, by iridium black.[1] Iridi pentafluorua có tính chất tương tự nhưng thật sự là một tetramer, Ir

4F

20, được tạo thành bởi bát diện dùng chung 4 góc.[1] Kim loại iridi tan trong cyanua-kali kim loại nóng chảy tạo ra ion Ir(CN)3+

6 (hexacyanoiridat).

A-xít hexachloroiridic(IV), H

2IrCl

6, và các muối của nó là những hợp chất iridi quan trong nhất trong lĩnh vực công nghiệp.[17] Chúng liên quan đến việc làm tinh khiết iridi và được sử dụng như các tiền chất để tạo các hợp chất iridi quan trọng khác, cũng như trong việc pha chế áo a-nốt. Ion IrCl2−

6 có màu nâu sẫm, và có thể dễ dàng bị khử thành IrCl3−

6 nhạt màu hơn và ngược lại.[17] Iridi trichlorua, IrCl

3, có thể thu được ở dạng anhydrat từ sự ô-xy hóa trực tiếp bột iridi bằng clo ở 650 °C,[17] hoặc dạng hydrat bằng cách hòa tan Ir

2O

3 trong axít hydrochloric, thường được dùng làm vật liệu ban đầu trong việc tổng hợp các hợp chất Ir(III) khác.[1] Hợp chất khác được sử dụng làm tiến chất là ammoni hexachloroiridat(III), (NH

4)

3IrCl

6. Các phức iridi(III) là nghịch từ (spin thấp) và thường có phân tử tám mặt đối xứng.[1]

Các hợp chất iridi hữu cơ chứa các liên kết iridi–carbon trong đó kim loại thường có trạng thái ô-xy hóa thấp hơn. Ví dụ, trong thái ô-xy hóa zero được phát hiện trong tetrairidi dodecacarbonyl, Ir

4(CO)

12, đây là một carbonyl của iridi hai cấu tử bền ổn định và phổ biến nhất.[1] Trong hợp chất này, mỗi nguyên tử iridi được liên kết đến 3 nguyên tử khác, tạo thành ô mạng tứ diện. Một vài hợp chất kim loại hữu cơ Ir(I) không đủ nổi tiếng để đặt tên sau khi được phát hiện ra. Ví dụ một chất là phức Vaska, IrCl(CO)[P(C

6H

5)

3]

2, nó có tính chất liên kết bất thường với phân tử ôxy, O

2.[18] Một chất khác là xúc tác Crabtree, xúc tác đồng nhất trong các phản ứng tạo hydro.[19] Các hợp chất này là đều là phẳng vuông?, phức d8, có tổng cộng 16 electron liên kết, chúng liên quan đến tính hoạt động của chất này.[20]

Một vật liệu hữu cơ gốc iridi LED đã được ghi nhận, và được phát hiện là sáng hơn nhiều so với DPA hoặc PPV, vì vậy nó có thể là nền tảng cho ánh sáng OLED chủ động trong tương lai.[21]

Đồng vị

Iridi có hai đồng vị bền trong tự nhiên là 191Ir và 193Ir, với thành phần thứ tự 37,3% và 62,7%.[22] Có ít nhất 34 đồng vị phóng xạ đã được tổng hợp có số khối từ 164 đến 199. 192Ir, nằm giữa hai đồng vị bền là đồng vị phóng xạ bề nhất với chu kỳ bán rã là 73,827 ngày, và được ứng dụng trong liệu pháp phóng xạ (điều trị bằng phóng xạ trong y học)[23] và trong chụp ảnh phóng xạ công nghiệp, đặc biệt trong các thí nghiệm không phá hủy các mối hàn của thép và trong công nghiệp dầu khí; các nguồn iridi-192 liên quan đến nhiều sự cố phóng xạ. Ba đồng vị khác có chu kỳ bán rã ít nhất một ngày—188Ir, 189Ir, và 190Ir.[22] Các đồng vị có số khối dưới 191 phân rã theo cách kết hợp giữa phân rã β+, α, và (hiếm hơn) phát xạ proton, ngoại trừ 189Ir phân rã bằng cách bắt giữ electron. Các đồng vị tổng hợp nặng hơn 191 phân rã β−, mặc dù 192Ir cũng có bắt giữ một ít electron.[22] Tất cả các đồng vị đã biết của iridi đã được phát hiện trong khoảng thời gian 1934 và 2001; đồng vị được phát hiện gần đây nhất là 171Ir.[24]

Ít nhất có 32 đồng phân hạt nhân đã được mô tả có số khối từ 164 đến 197. Đồng phân ổn định nhất là 192m2Ir, nó phân rã thành đồng phân chuyển tiếp với chu kỳ bán rã 241 năm,[22] nên nó là đồng phân ở định hơn trong tất cả các đồng vị tổng hợp ở trạng thái ổn định. Đồng phân kém bền nhất là 190m3Ir có chu kỳ bán rã chỉ 2 µ giây.[22] Đồng vị 191Ir là đồng vị đầu tiên trong bất kỳ nguyên tổ nào thể hiện hiệu ứng Mössbauer. Điều này rất hữu ích trong kính quang phổ Mössbauer trong nghiên cứu vật lý, hóa học, sinh hóa, luyện kim và khoáng vật học.[25]

Lịch sử

Việc phát hiện ra iridi đan xen với việc phát hiện ra platin và các kim loại khác trong nhóm platin. Platin tự sinh được sử dụng bởi người Ethiopia cổ đại[26] và trong các nền văn hóa Nam Mỹ[27] cũng có chứa một lượng nhỏ các kim loại khác thuộc nhóm platin bao gồm cả iridi. Platin đến Châu Âu với tên gọi là platina ("silverette"), được tìm thấy trong thế kỷ 17 bởi những kẻ xâm lược người Tây Ban Nha trong vùng mà ngày nay được gọi là Chocó ở Colombia.[28] Việc phát hiện kim loại này không ở dạng hợp kim của các nguyên tố đã biết, nhưng thay vào đó là một nguyên tố hoàn toàn mới, mà đã không được biết đến cho mãi tới năm 1748.[29]

Các nhà hóa học nghiên cứu platin đã hòa tan nó trong nước cường toan để tạo ra các muối tan. Chúng được quan sát từ một lượng nhỏ có màu sẫm, chất còn lại không tan.[2] Joseph Louis Proust đã nghĩ rằng chất không tan này là graphit.[2] Các nhà hóa học Pháp Victor Collet-Descotils, Antoine François, comte de Fourcroy, và Louis Nicolas Vauquelin cũng đã quan sát chất cặn này năm 1803, nhưng không thu thập đủ cho các thí nghiệm sau đó.[2]

Năm 1803, nhà khoa học Anh Smithson Tennant (1761–1815) đã phân tích chất cặn không tan và kết luận rằng nó phải chứa một kim loại mới. Vauquelin đã xử lý bột trộnvo71i7 kiềm và các axit[8] và thu được một ôxit dễ bay hơn mới, mà từ đó ông tin rằng đây là kim loại mới, ông đặt tên nó là ptene, trong tiếng Hy Lạp πτηνός ptēnós nghĩa là "cánh chim".[30][31] Tennant đã có thuận lợi hơn trong việc thu được lượng cặn lớn hơn, và ông tiếp tục nghiên cứu của mình và xác định hai nguyên tố mà trước đó chưa được phát hiện trong chất cặn đen, là iridi và osmi.[2][8] Ông thu được các tinh thể màu đỏ sẫm (có lẽ là Na

2[IrCl

6]·nH

2O) bằng một chuỗi các phản ứng với natri hydroxit và axit clohydric.[31] Ông đặt tên iridium theo tên Iris (Ἶρις), the Greek winged goddess of the rainbow and the messenger of the Olympian gods, bởi vì nhiều muối mà ông thu được có nhiều màu.[note 2][32] Việc phát hiện ra nguyên tố mới được ghi nhận trong một lá thư gởi Hiệp hội hoàng gia ngày 21 tháng 6 năm 1804.[2][33]

Nhà khoa học người Anh John George Children là người đầu tiên nấu chảy mẫu iridi năm 1813 với sự trợ giúp của "pin mạ lớn nhất từng được chế tạo" (vào lúc đó).[2] Lần đầu tiên thu nhận được iridi độ tinh khiết cao do Robert Hare thực hiện năm 1842. Ông đã phát hiện nó có tỉ trọng khoảng 21,8 g/cm3 và ghi nhận rằng kim lọai này gần như không thể uốn và rất cứng. Việc nấu chảy đầu tiên với số lượng đáng kể được thực hiện bởi Henri Sainte-Claire Deville và Jules Henri Debray năm 1860. Họ đã đốt hơn 300 lit khí O

2 và H

2 tinh khiết để thu được mỗi kg iridi.[2]

Những điểm cực kỳ khó trong việc nung chảy kim loại đã làm hạn chế khả năng xử lý iridi. John Isaac Hawkins was looking to obtain a fine and hard point for fountain pen nibs, và năm 1834 đã kiểm soát việc tạo ra bút vàng có đầu iridi. Năm 1880, John Holland và William Lofland Dudley đã có thể nấu chảy iridi bằng cách cho thêm phốt pho vào và nhận được bằng sáng chế công nghệ này ở Hoa Kỳ; Công ty Anh Johnson Matthey sau đó đã chỉ ra họ đã đang sử dụng công nghệ tương tự từ năm 1837 và đã trình diễn nấu chảy iridi tại nhiều hội chợ Thế Giới.[2] Ứng dụng đầu tiên của hợp kim iridi và rutheni là làm cặp nhiệt điện, nó được tạo ra bởi Otto Feussner năm 1933. Cặp nhiệt điện này cho phép đo nhiệt độ trong không khí lên đến 2000 °C.[2]

Ở Munich, Đức vào năm 1957 Rudolf Mössbauer, trong bối cảnh được gọi là "một trong những thí nghiệm ấn tượng của vật lý thế kỷ 20",[34] đã phát hiện ra sự cộng hưởng và recoil-phát xạ và hấp thụ tự do các tia gama bởi các nguyên tử trong kim loại rắn chỉ chứa 191Ir.[35] Hiện tượng này được gọi là hiệu ứng Mössbauer (từng được quan sát trên các hạt nhân khác như 57Fe), và đã phát triển thành quang phổ Mössbauer, đã có những đóng góp quan trọng trong nghiên cứu vật lý, hóa học, sinh hóa, luyện kim, và khoáng vật học.[25] Mössbauer đã nhận giải Giải Nobel vật lý năm 1961 ở tuổi 32, chỉ 3 năm sau khi phát hiện của ông được công bố.[36] Năm 1986 Rudolf Mössbauer đã được vinh dự nhận được huy chương Albert Einstein và Elliot Cresson từ thành tựu này.

Phân bố

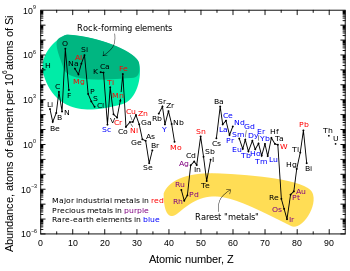

Iridi là một trong 9 nguyên tố bền ít phổ biến nhất trong vỏ trái đất, có tỉ lệ khối trung bình 0,001 ppm trong đá của vỏ; trong khi vàng phổ biến hơn gấp 40 lần, platin gấp 10 lần, và bạc và thủy ngân gấp 80 lần.[1] Telluri có độ phổ biến bằng với iridi.[1] Ngược lại với tính phố biến thấp của nó trong đá của vỏ, iridi tương đối phổ biến trong các thiên thạch, với hàm lượng 0,5 ppm hoặc hơn.[38] Tổng hàm lượng iridi trên Trái đất được cho rằng lớn hơn nhiều so với những gì đã quan sát được trong đá của vỏ, nhưng do mật độ và tính siderophilic ("ái sắt") của iridi, nó chìm xuống bên dưới vỏ và đi vào trong lõi Trái đất khi hành tinh còn ở trạng thái nói chảy.[17]

Iridi được tìm thấy trong tự nhiên ở dạng nguyên tố không kết hợp hoặc trong dạng hợp kim tự nhiên; đặc biệt là các hợp kim iridi–osmis, osmiridi (giàu osmi), và iridosmi (giàu iridi).[8] Trong các mỏ nikel và đồng, các kim loại platin tồn tại ở dạng sulfua (như (Pt,Pd)S), tellurua (như PtBiTe), antimonua (PdSb), và arsenua (như PtAs

2). Trong tất cả các hợp chất này, platin là được trao đổi bởi môt lượng nhỏ iridi và osmi. Cũng như với tất cả các kim loại nhóm platin, iridi có thể được tìm thấy trong tự nhiên ở dạng hợp kim với nikel tự sinh hoặc đồng tự sinh.[39]

Trong vỏ Trái đất, iridi được tìm thấy với hàm lượng cao nhất trong ba kiểu cấu trúc địa chất: quặng mácma (các thể mácma xâm nhập từ bên dưới), các hố va chạm, và quặng tái lắng đọng từ một trong các cấu trúc vừa kể trên. Trữ lượng nguyên sinh lớn nhất từng được biết là trong [[phức hệ mácma Bushveld[[ ở Nam Phi,[40] mặc dù các lớn khác là mỏ đồng-nikel lớn gần Norilsk ở Nga, và bồn trũng Sudbury ở Canada cũng có một lượng đáng kể iridi. Các trữ lượng nhỏ hơn được tìm thấy ở Hoa Kỳ.[40] Iridi cũng được tìm thấy ở dạng mỏ thứ sinh cùng với platin và các kim loại nhóm platin trong các trầm tích sông. Mỏ nguồn gốc sông được sử dụng bởi người tiền Columbia vùng Chocó, Colombia vẫn là nguồn cung cấp kim loại nhóm platin. Cho đến năm 2003, trữ lượng trên thế giới vẫn chưa được ước lượng.[8]

Có mặt trong ranh giới tuyệt chủng Creta-Paleogen

Ranh giới Kỷ Creta-Paleogen cách đây 66 triệu năm, đánh dấu mốc thời gian giữa Kỷ Creta và Paleogen trong thang thời gian địa chất, được xác định từ một lớp địa tầng mỏng là sét giàu iridi.[41] Một nhóm nghiên cứu dẫn đầu là Luis Alvarez đã đề xuất năm 1980 về nguồn gốc ngoài trái đất của lượng iridi này, đó là do sự va chạm của một tiểu hành tinh hay sao chỗi.[41] Giả thuyết của họ, được gọi là giả thiết Alvarez, hiện được chấp nhận rộng rãi để giải thích sự kiện tuyệt chủng các loài khủng long phi chim. Một hố va chạm lớn bị chôn vùi với tuổi ước tính khoảng 66 triệu năm sau đó được xác định nằm ở nơi mà ngày nay là bán đảo Yucatán (tên gọi hố va chạm Chicxulub).[42][43] Dewey M. McLean và những người khác đã tranh luận rằng iridi có thể có nguồn gốc phun trào, do lõi Trái đất giàu iridi, và các núi lửa hoạt động như Piton de la Fournaise, ở đảo Réunion, vẫn đang giải phóng iridi.[44][45]

Sản xuất

| Năm | Tiêu thụ (tấn) |

Price (USD/ozt)[46] |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2.6 | 415.25 |

| 2002 | 2.5 | 294.62 |

| 2003 | 3.3 | 93.02 |

| 2004 | 3.60 | 185.33 |

| 2005 | 3.86 | 169.51 |

| 2006 | 4.08 | 349.45 |

| 2007 | 3.70 | 444.43 |

| 2008 | 3.10 | 448.34 |

| 2009 | 2.52 | 420.4 |

| 2010 | 10.40 | 642.15 |

Iridi được sản xuất thương mại ở dạng sản phẩm phụ của quá trình khai thác mỏ và chế biến nickel và đồng. Trong quá trình điện luyện đồng và nickel, các kim loại hiếm như bạc, vàng và kim loại nhóm platin cũng như selenium và tellurium lắng đọng ở đáy lò ở dạng "bùn anốt", là điểm khởi đầu của việc tách chúng.[46] Để tách các kim loại này, chúng phải được chuyển thành dung dịch. Nhiều phương pháp tách khách nhau có thể áp dụng tùy theo thành phần của hỗn hợp; hai phương pháp điển hình là phản ứng với natri peroxit sau khi hòa tan bằng nước cường toan, và phương pháp hòa tan vào hỗn hợp clo bằng axit hydrochloric.[17][40]

Sau khi hỗn hợp được hòa tan, iridi được tách ra khỏi nhóm kim loại platin bằng cách tạo kết tủa ammonium hexachloroiridate ((NH

4)

2IrCl

6) hoặc tách IrCl2−

6 bằng các amin hữu hơ.[47] Phương pháp kết tủa tương tự như quy trình Tennant và Wollaston sử dụng để tách chúng. Phương pháp thứ 2 có thể được thực hiện bằng cách chiết tách chất lỏng-chất lỏng liên tục và thích hợp hơn với sản xuất quy mô công nghiệp. Trong cả hai trường hợp, sản phẩm được khử bằng hydro, tạo ra kim loại ở dạng bột hoặc kim loại dạng bọt, loại này có thể được xử lý bằng các kỹ thuật luyện kim bột.[48][49]

Giá iridi dao động trong khoảng đáng kể. Với khối lượng tương đối nhỏ trên thị trường thế giới (so với các kim loại công nghiệp khác như nhôm hay đồng), giá iridi thay đổi mạnh với sự không ổn định về sản lượng, nhu cầu, speculation, tích trữ, và tình hình chính trong ở các quốc gia sản xuất. Là một chất có các tính chất hiếm, giá của nó đặc biệt bị ảnh hưởng bởi những thay đổi của công nghệ hiện đại: Giá nó giảm liên tục trong khoảng 2001 và 2003 liên quan đến tình trạng thừa cung từ các lò nấu Ir được sử dụng trong phát triển công nghiệp các tinh thể lớn đơn lẻ.[46][50] Tương tự giá đạt trên 1000 USD/oz trong khoảng 2010 và 2014 được giải thích là do việc lắp đặt các nhà máy tổng hợp tinh thể sapphire đơn dùng trong LED TV.[51]

Ứng dụng

Nhu cầu iridi dao động trong khoảng từ 2,5 tấn năm 2009 đến 10,4 năm 2010, hầu hết là các ứng dụng liên quan đến điện tử làm tăng từ 0,2 đến 6 tấn – các nồi nấu kim loại iridi được sử dụng phổ biến để nuôi các tinh thế đơn lẻ chất lượng cao, làm cho nhu cầu tăng mạnh. Việc tăng lượng tiêu thụ iridi được dự đoán đạt bảo hòa vì được dồn vào các lò nấu kim loại, như đã diễn ra trước đây torng thập niên 2000. Các ứng dụng chính khác như làm bugi đánh lửa tiêu thụ 0,78 tấn iridi năm 2007, điện cực trong công nghệ chloralkali (1,1 tấn năm 2007) và xúc tác hóa học (0,75 năm 2007).[46][52]

Trong công nghiệp và y học

3

Tính chống mòn, độ cứng và nóng chảy cao của iridi và các kim loại của nó định hình nên hầu hết các ứng dụng của chúng. Iridi và đặc biệt là hợp kim iridi-platin hoặc iridi-osmi có a low wear và được sử dụng, ví dụ for multi-pored spinnerets, qua đó polymer plastic tan chảy được đẩy ra tạo thành các sợi như rayon.[53] Osmi–iridi được dùng làm vòng la bàn và để giữa thăng bằng.[54]

Bài viết này là công việc biên dịch đang được tiến hành từ bài viết [[:FromLanguage:|]] từ một ngôn ngữ khác sang tiếng Việt. Bạn có thể giúp Wikipedia bằng cách hỗ trợ dịch và trau chuốt lối hành văn tiếng Việt theo cẩm nang của Wikipedia. |

Their resistance to arc erosion makes iridium alloys ideal for electrical contacts for spark plugs,[55][56] and iridium-based spark plugs are particularly used in aviation.

Pure iridium is extremely brittle, to the point of being hard to weld because the heat-affected zone cracks, but it can be made more ductile by addition of small quantities of titanium and zirconium (0.2% of each apparently works well)[57]

Corrosion and heat resistance makes iridium an important alloying agent. Certain long-life aircraft engine parts are made of an iridium alloy, and an iridium–titanium alloy is used for deep-water pipes because of its corrosion resistance.[8] Iridium is also used as a hardening agent in platinum alloys. The Vickers hardness of pure platinum is 56 HV, whereas platinum with 50% of iridium can reach over 500 HV.[58][59]

Devices that must withstand extremely high temperatures are often made from iridium. For example, high-temperature crucibles made of iridium are used in the Czochralski process to produce oxide single-crystals (such as sapphires) for use in computer memory devices and in solid state lasers.[55][60] The crystals, such as gadolinium gallium garnet and yttrium gallium garnet, are grown by melting pre-sintered charges of mixed oxides under oxidizing conditions at temperatures up to 2100 °C.[2]

Iridium compounds are used as catalysts in the Cativa process for carbonylation of methanol to produce acetic acid.[61]

The radioisotope iridium-192 is one of the two most important sources of energy for use in industrial γ-radiography for non-destructive testing of metals.[62][63] Additionally, 192Ir is used as a source of gamma radiation for the treatment of cancer using brachytherapy, a form of radiotherapy where a sealed radioactive source is placed inside or next to the area requiring treatment. Specific treatments include high-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy, bilary duct brachytherapy, and intracavitary cervix brachytherapy.[8]

Iridium is a good catalyst for the decomposition of hydrazine (into hot nitrogen and ammonia), and this is used in practice in low-thrust rocket engines; there are more details in the monopropellant rocket article.

Trong khoa học

An alloy of 90% platinum and 10% iridium was used in 1889 to construct the International Prototype Metre and kilogram mass, kept by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures near Paris.[8] The meter bar was replaced as the definition of the fundamental unit of length in 1960 by a line in the atomic spectrum of krypton,[note 3][64] but the kilogram prototype is still the international standard of mass.[65]

Iridium has been used in the radioisotope thermoelectric generators of unmanned spacecraft such as the Voyager, Viking, Pioneer, Cassini, Galileo, and New Horizons. Iridium was chosen to encapsulate the plutonium-238 fuel in the generator because it can withstand the operating temperatures of up to 2000 °C and for its great strength.[2]

Another use concerns X-ray optics, especially X-ray telescopes.[66] The mirrors of the Chandra X-ray Observatory are coated with a layer of iridium 60 nm thick. Iridium proved to be the best choice for reflecting X-rays after nickel, gold, and platinum were also tested. The iridium layer, which had to be smooth to within a few atoms, was applied by depositing iridium vapor under high vacuum on a base layer of chromium.[67]

Iridium is used in particle physics for the production of antiprotons, a form of antimatter. Antiprotons are made by shooting a high-intensity proton beam at a conversion target, which needs to be made from a very high density material. Although tungsten may be used instead, iridium has the advantage of better stability under the shock waves induced by the temperature rise due to the incident beam.[68]

Carbon–hydrogen bond activation (C–H activation) is an area of research on reactions that cleave carbon–hydrogen bonds, which were traditionally regarded as unreactive. The first reported successes at activating C–H bonds in saturated hydrocarbons, published in 1982, used organometallic iridium complexes that undergo an oxidative addition with the hydrocarbon.[69][70]

Iridium complexes are being investigated as catalysts for asymmetric hydrogenation. These catalysts have been used in the synthesis of natural products and able to hydrogenate certain difficult substrates, such as unfunctionalized alkenes, enantioselectively (generating only one of the two possible enantiomers).[71][72]

Iridium forms a variety of complexes of fundamental interest in triplet harvesting.[73][74][75]

Trong nghiên cứu lịch sử

Iridium–osmium alloys were used in fountain pen nib tips. The first major use of iridium was in 1834 in nibs mounted on gold.[2] Since 1944, the famous Parker 51 fountain pen was fitted with a nib tipped by a ruthenium and iridium alloy (with 3.8% iridium). The tip material in modern fountain pens is still conventionally called "iridium", although there is seldom any iridium in it; other metals such as ruthenium, osmium and tungsten have taken its place.[76]

An iridium–platinum alloy was used for the touch holes or vent pieces of cannon. According to a report of the Paris Exhibition of 1867, one of the pieces being exhibited by Johnson and Matthey "has been used in a Withworth gun for more than 3000 rounds, and scarcely shows signs of wear yet. Those who know the constant trouble and expense which are occasioned by the wearing of the vent-pieces of cannon when in active service, will appreciate this important adaptation".[77]

The pigment iridium black, which consists of very finely divided iridium, is used for painting porcelain an intense black; it was said that "all other porcelain black colors appear grey by the side of it".[78]

Ứng dụng

Iridi được sử dụng như một thành phần của các hợp kim dùng cho các cặp nhiệt điện; nồi nấu kim loại, hoặc các điện cực cho các buji động cơ máy bay.

- Hợp kim bạch kim - iridi: các công tắc điện; đồ trang sức; kim khâu dưới da

- Hợp kim rodi - iridi: cặp nhiệt điện

- Hợp kim iridi - osimi: đầu bút

- Hợp kim iridi - vonfram: dây tóc nhiệt độ cao

Chú ý

Iridi ở dạng khối kim loại không có vai trò sinh học quan trọng hoặc nguy hiểm đối với sức khỏe do nó không phản ứng với các tế bào; chỉ có khoảng 20 ppt (một phần tỉ) iridi có mặt trong tế bào.[8] Tuy nhiên, bột iridi mịn có thể nguy hiểm khi tiếp xúc, vì nó là một chất kích thích và có thể cháy trong không khí.[40] Có rất ít thông tin về độc tính của các hợp chất iridi do chúng được sử dụng với số lượng rất nhỏ, nhưng các muối hòa tan như iridi halua, có thể nguy hiểm do các nguyên tố khác trong hợp chất hơn là do iridi.[23] Hầu hết các hợp chất iridi không hòa tan nên nó khó hấp thụ vào trong cơ thể.[8]

Đồng vị phóng xạ của iridi, 192Ir thì nguy hiểm giống như các đồng vị phóng xạ khác. Tổn thương được thông báo duy nhất liên quan đến việc tiếp xúc 192Ir là loại được dùng trong liệu pháp tia phóng xạ để gần.[23] Bức xạ gama năng lượng cao của 192Ir có thể làm tăng nguy cơ gây ung thư. Tiếp xúc bên ngoài có thể gây bỏng, nhiễm độc phóng xạ, và chết. Ăn 192Ir vào có thể đốt cháy lớp lót dạ dày và ruột.[79] 192Ir, 192mIr, và 194mIr có xu hướng tích tụ trong gan, và có thể gây nguy hiểm cho sức khỏe do bức xạ beta và gamma.[38]

Chú thích

- ^ Các trạng thái ôxy hóa phổ biến nhất của iridi được in đậm. Cột bên phải liệt kê một hợp chất đặc trưng cho trạng thái ôxy hóa đó.

- ^ Iridium literally means "of rainbows".

- ^ The definition of the meter was changed again in 1983. The meter is currently defined as the distance traveled by light in a vacuum during a time interval of 1⁄299,792,458 of a second.

Tham khảo

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Greenwood, N. N. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (ấn bản 2). Oxford: Butterworth–Heinemann. tr. 1113–1143, 1294. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4. OCLC 213025882 37499934 41901113 Kiểm tra giá trị

|oclc=(trợ giúp). Đã bỏ qua tham số không rõ|coauthors=(gợi ý|author=) (trợ giúp) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hunt, L. B. (1987). “A History of Iridium” (PDF). Platinum Metals Review. 31 (1): 32–41. Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>không hợp lệ: tên “hunt” được định rõ nhiều lần, mỗi lần có nội dung khác - ^ Kittel, C. (2004). Introduction to Solid state Physics, 7th Edition. Wiley-India. ISBN 8126510455.

- ^ Arblaster, J. W. (1995). “Osmium, the Densest Metal Known”. Platinum Metals Review. 39 (4): 164.

- ^ Cotton, Simon (1997). Chemistry of Precious Metals. Springer-Verlag New York, LLC. tr. 78. ISBN 9780751404135.

- ^ Lide, D. R. (1990). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (70th Edn.). Boca Raton (FL):CRC Press.

- ^ Arblaster, J. W. (1989). “Densities of osmium and iridium: recalculations based upon a review of the latest crystallographic data” (PDF). Platinum Metals Review. 33 (1): 14–16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Emsley, J. (2003). “Iridium”. Nature's Building Blocks: An A–Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press. tr. 201–204. ISBN 0-19-850340-7. Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>không hợp lệ: tên “Emsley” được định rõ nhiều lần, mỗi lần có nội dung khác - ^ a b Perry, D. L. (1995). Handbook of Inorganic Compounds. CRC Press. tr. 203–204. ISBN 0-8492-8671-3 Kiểm tra giá trị

|isbn=: giá trị tổng kiểm (trợ giúp). - ^ Lagowski, J. J. biên tập (2004). Chemistry Foundations and Applications. 2. Thomson Gale. tr. 250–251. ISBN 0-02-865732-3 Kiểm tra giá trị

|isbn=: giá trị tổng kiểm (trợ giúp). - ^ Jung, D.; Demazeau, Gérard (1995). “High Oxygen Pressure and the Preparation of New Iridium (VI) Oxides with Perovskite Structure: Sr

2MIrO

6 (M = Ca, Mg)”. Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 115 (2): 447–455. Bibcode:1995JSSCh.115..447J. doi:10.1006/jssc.1995.1158. - ^ Gong, Y.; Zhou, M.; Kaupp, M.; Riedel, S. (2009). “Formation and Characterization of the Iridium Tetroxide Molecule with Iridium in the Oxidation State +VIII”. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 48: 7879–7883. doi:10.1002/anie.200902733.Quản lý CS1: nhiều tên: danh sách tác giả (liên kết)

- ^ Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>sai; không có nội dung trong thẻ ref có tênIrIX - ^ Gulliver, D. J; Levason, W. (1982). “The chemistry of ruthenium, osmium, rhodium, iridium, palladium and platinum in the higher oxidation states”. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 46: 1–127. doi:10.1016/0010-8545(82)85001-7.

- ^ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E.; Wiberg, N. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry (ấn bản 1). Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-352651-5. OCLC 47901436.

- ^ Černý, R.; Joubert, J.-M.; Kohlmann, H.; Yvon, K. (2002). “Mg

6Ir

2H

11, a new metal hydride containing saddle-like IrH5−

4 and square-pyramidal IrH4−

5 hydrido complexes”. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 340 (1–2): 180–188. doi:10.1016/S0925-8388(02)00050-6. - ^ a b c d e Renner, H.; Schlamp, G.; Kleinwächter, I.; Drost, E.; Lüschow, H. M.; Tews, P.; Panster, P.; Diehl, M.; và đồng nghiệp (2002). “Platinum group metals and compounds”. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_075.

- ^ Vaska, L.; DiLuzio, J.W. (1961). “Carbonyl and Hydrido-Carbonyl Complexes of Iridium by Reaction with Alcohols. Hydrido Complexes by Reaction with Acid”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 83 (12): 2784–2785. doi:10.1021/ja01473a054.

- ^ Crabtree, R. H. (1979). “Iridium compounds in catalysis”. Accounts of Chemical Research. 12 (9): 331–337. doi:10.1021/ar50141a005.

- ^ Crabtree, R. H. (2005). The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals (PDF). Wiley. ISBN 0471662569. OCLC 224478241.

- ^ Research and Development. furuyametals.co.jp

- ^ a b c d e Audi, G.; Bersillon, O.; Blachot, J.; Wapstra, A.H. (2003). “The NUBASE Evaluation of Nuclear and Decay Properties”. Nuclear Physics A. Atomic Mass Data Center. 729: 3–128. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001.

- ^ a b c Mager Stellman, J. (1998). “Iridium”. Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety. International Labour Organization. tr. 63.19. ISBN 9789221098164. OCLC 35279504 45066560 Kiểm tra giá trị

|oclc=(trợ giúp). - ^ Arblaster, J. W. (2003). “The discoverers of the iridium isotopes: the thirty-six known iridium isotopes found between 1934 and 2001”. Platinum Metals Review. 47 (4): 167–174.

- ^ a b Chereminisoff, N. P. (1990). Handbook of Ceramics and Composites. CRC Press. tr. 424. ISBN 0-8247-8006-X.

- ^ Ogden, J. M. (1976). “The So-Called 'Platinum' Inclusions in Egyptian Goldwork”. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 62: 138–144. doi:10.2307/3856354. JSTOR 3856354.

- ^ Chaston, J. C. (1980). “The Powder Metallurgy of Platinum” (PDF). Platinum Metals Rev. 24 (21): 70–79.

- ^ McDonald, M. (1959). “The Platinum of New Granada: Mining and Metallurgy in the Spanish Colonial Empire”. Platinum Metals Review. 3 (4): 140–145.

- ^ Juan, J.; de Ulloa, A. (1748). Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional (bằng tiếng Spanish). 1. tr. 606.Quản lý CS1: ngôn ngữ không rõ (liên kết)

- ^ Thomson, T. (1831). A System of Chemistry of Inorganic Bodies. Baldwin & Cradock, London; and William Blackwood, Edinburgh. tr. 693.

- ^ a b Griffith, W. P. (2004). “Bicentenary of Four Platinum Group Metals. Part II: Osmium and iridium – events surrounding their discoveries”. Platinum Metals Review. 48 (4): 182–189. doi:10.1595/147106704X4844.

- ^ Weeks, M. E. (1968). Discovery of the Elements (ấn bản 7). Journal of Chemical Education. tr. 414–418. ISBN 0-8486-8579-2. OCLC 23991202.

- ^ Tennant, S. (1804). “On Two Metals, Found in the Black Powder Remaining after the Solution of Platina”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 94: 411–418. doi:10.1098/rstl.1804.0018. JSTOR 107152.

- ^ Trigg, G. L. (1995). Landmark Experiments in Twentieth Century Physics. Courier Dover Publications. tr. 179–190. ISBN 0-486-28526-X. OCLC 31409781.

- ^ Mössbauer, R. L. (1958). “Gammastrahlung in Ir191”. Zeitschrift für Physik A (bằng tiếng German). 151 (2): 124–143. Bibcode:1958ZPhy..151..124M. doi:10.1007/BF01344210.Quản lý CS1: ngôn ngữ không rõ (liên kết)

- ^ Waller, I. (1964). “The Nobel Prize in Physics 1961: presentation speech”. Nobel Lectures, Physics 1942–1962. Elsevier.

- ^ Scott, E. R. D.; Wasson, J. T.; Buchwald, V. F. (1973). “The chemical classification of iron meteorites—VII. A reinvestigation of irons with Ge concentrations between 25 and 80 ppm”. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 37 (8): 1957–1983. Bibcode:1973GeCoA..37.1957S. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(73)90151-8.

- ^ a b “Iridium” (PDF). Human Health Fact Sheet. Argonne National Laboratory. 2005. Truy cập ngày 20 tháng 9 năm 2008.

- ^ Xiao, Z.; Laplante, A. R. (2004). “Characterizing and recovering the platinum group minerals—a review”. Minerals Engineering. 17 (9–10): 961–979. doi:10.1016/j.mineng.2004.04.001.

- ^ a b c d Seymour, R. J. (2001). “Platinum-group metals”. Kirk Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Wiley. doi:10.1002/0471238961.1612012019052513.a01.pub2. Đã bỏ qua tham số không rõ

|coauthors=(gợi ý|author=) (trợ giúp) - ^ a b Alvarez, L. W.; Alvarez, W.; Asaro, F.; Michel, H. V. (1980). “Extraterrestrial cause for the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction”. Science. 208 (4448): 1095–1108. Bibcode:1980Sci...208.1095A. doi:10.1126/science.208.4448.1095. PMID 17783054.

- ^ Hildebrand, A. R.; Penfield, Glen T.; Kring, David A.; Pilkington, Mark; Zanoguera, Antonio Camargo; Jacobsen, Stein B.; Boynton, William V. (1991). “Chicxulub Crater; a possible Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary impact crater on the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico”. Geology. 19 (9): 867–871. Bibcode:1991Geo....19..867H. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1991)019<0867:CCAPCT>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ Frankel, C. (1999). The End of the Dinosaurs: Chicxulub Crater and Mass Extinctions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47447-7. OCLC 40298401.

- ^ Ryder, G.; Fastovsky, D. E.; Gartner, S. (1996). The Cretaceous-Tertiary Event and Other Catastrophes in Earth History. Geological Society of America. tr. 47. ISBN 0-8137-2307-8.

- ^ Toutain, J.-P.; Meyer, G. (1989). “Iridium-Bearing Sublimates at a Hot-Spot Volcano (Piton De La Fournaise, Indian Ocean)”. Geophysical Research Letters. 16 (12): 1391–1394. Bibcode:1989GeoRL..16.1391T. doi:10.1029/GL016i012p01391.

- ^ a b c d Platinum-Group Metals. U.S. Geological Survey Mineral Commodity Summaries

- ^ Gilchrist, Raleigh (1943). “The Platinum Metals”. Chemical Reviews. 32 (3): 277–372. doi:10.1021/cr60103a002.

- ^ Ohriner, E. K. (2008). “Processing of Iridium and Iridium Alloys”. Platinum Metals Review. 52 (3): 186–197. doi:10.1595/147106708X333827.

- ^ Hunt, L. B.; Lever, F. M. (1969). “Platinum Metals: A Survey of Productive Resources to industrial Uses” (PDF). Platinum Metals Review. 13 (4): 126–138.

- ^ Hagelüken, C. (2006). “Markets for the catalysts metals platinum, palladium, and rhodium” (PDF). Metall. 60 (1–2): 31–42.

- ^ “Platinum 2013 Interim Review” (PDF). Platinum Today. Johnson Matthey Plc. Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 1 năm 2014.

- ^ Jollie, D. (2008). Platinum 2008 (PDF). Johnson Matthey. ISSN 0268-7305. Truy cập ngày 13 tháng 10 năm 2008.

- ^ Egorova, R. V.; Korotkov, B. V.; Yaroshchuk, E. G.; Mirkus, K. A.; Dorofeev N. A.; Serkov, A. T. (1979). “Spinnerets for viscose rayon cord yarn”. Fibre Chemistry. 10 (4): 377–378. doi:10.1007/BF00543390.

- ^ Emsley, J. (18 tháng 1 năm 2005). “Iridium” (PDF). Visual Elements Periodic Table. Royal Society of Chemistry. Truy cập ngày 17 tháng 9 năm 2008.

- ^ a b Handley, J. R. (1986). “Increasing Applications for Iridium” (PDF). Platinum Metals Review. 30 (1): 12–13.

- ^ Stallforth, H.; Revell, P. A. (2000). Euromat 99. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-30124-9.

- ^ Đăng ký phát minh US 3293031A, "{{{title}}}", trao vào [[{{{gdate}}}]]

- ^ Darling, A. S. (1960). “Iridium Platinum Alloys” (PDF). Platinum Metals Review. 4 (l): 18–26. Truy cập ngày 13 tháng 10 năm 2008.

- ^ Biggs, T.; Taylor, S. S.; van der Lingen, E. (2005). “The Hardening of Platinum Alloys for Potential Jewellery Application”. Platinum Metals Review. 49 (1): 2–15. doi:10.1595/147106705X24409.

- ^ Crookes, W. (1908). “On the Use of Iridium Crucibles in Chemical Operations”. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 80 (541): 535–536. Bibcode:1908RSPSA..80..535C. doi:10.1098/rspa.1908.0046. JSTOR 93031.

- ^ Cheung, H.; Tanke, R. S.; Torrence, G. P. (2000). “Acetic acid”. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_045.

- ^ Halmshaw, R. (1954). “The use and scope of Iridium 192 for the radiography of steel”. British Journal of Applied Physics. 5 (7): 238–243. Bibcode:1954BJAP....5..238H. doi:10.1088/0508-3443/5/7/302.

- ^ Hellier, Chuck (2001). Handbook of Nondestructive Evlaluation. The McGraw-Hill Companies. ISBN 978-0-07-028121-9.

- ^ Penzes, W. B. (2001). “Time Line for the Definition of the Meter”. National Institute for Standards and Technology. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 9 năm 2008.

- ^ General section citations: Recalibration of the U.S. National Prototype Kilogram, R. S. Davis, Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards, 90, No. 4, July–August 1985 (5.5 MB PDF, here); and The Kilogram and Measurements of Mass and Force, Z. J. Jabbour et al., J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 106, 2001, 25–46 (3.5 MB PDF, here)

- ^ Ziegler, E.; Hignette, O.; Morawe, Ch.; Tucoulou, R. (2001). “High-efficiency tunable X-ray focusing optics using mirrors and laterally-graded multilayers”. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment. 467–468: 954–957. Bibcode:2001NIMPA.467..954Z. doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(01)00533-2.

- ^ “Face-to-Face with Jerry Johnston, CXC Program Manager & Bob Hahn, Chief Engineer at Optical Coating Laboratories, Inc., Santa Rosa, CA”. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics; Chandra X-ray Center. 1995. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 9 năm 2008.

- ^ Möhl, D. (1997). “Production of low-energy antiprotons”. Zeitschrift Hyperfine Interactions. 109: 33–41. Bibcode:1997HyInt.109...33M. doi:10.1023/A:1012680728257.

- ^ a b Janowicz, A. H.; Bergman, R. G. (1982). “Carbon-hydrogen activation in completely saturated hydrocarbons: direct observation of M + R-H -> M(R)(H)”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 104 (1): 352–354. doi:10.1021/ja00365a091.

- ^ a b Hoyano, J. K.; Graham, W. A. G. (1982). “Oxidative addition of the carbon-hydrogen bonds of neopentane and cyclohexane to a photochemically generated iridium(I) complex”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 104 (13): 3723–3725. doi:10.1021/ja00377a032.

- ^ Källström, K; Munslow, I; Andersson, P. G. (2006). “Ir-catalysed asymmetric hydrogenation: Ligands, substrates and mechanism”. Chemistry: A European Journal. 12 (12): 3194–3200. doi:10.1002/chem.200500755. PMID 16304642.

- ^ Roseblade, S. J.; Pfaltz, A. (2007). “Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of olefins”. Accounts of Chemical Research. 40 (12): 1402–1411. doi:10.1021/ar700113g. PMID 17672517.

- ^ Wang, X.; Andersson, M. R.; Thompson, M. E.; Inganäsa, O. (2004). “Electrophosphorescence from substituted poly(thiophene) doped with iridium or platinum complex”. Thin Solid Films. 468 (1–2): 226–233. Bibcode:2004TSF...468..226W. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2004.05.095.

- ^ Tonzetich, Zachary J. (2002). “Organic Light Emitting Diodes—Developing Chemicals to Light the Future” (PDF). Journal of Undergraduate Research. Rochester University. 1 (1). Truy cập ngày 10 tháng 10 năm 2008.

- ^ Holder, E.; Langefeld, B. M. W.; Schubert, U. S. (25 tháng 4 năm 2005). “New Trends in the Use of Transition Metal-Ligand Complexes for Applications in Electroluminescent Devices”. Advanced Materials. 17 (9): 1109–1121. doi:10.1002/adma.200400284.

- ^ Mottishaw, J. (1999). “Notes from the Nib Works—Where's the Iridium?”. The PENnant. XIII (2).

- ^ Crookes, W. biên tập (1867). “The Paris Exhibition”. The Chemical News and Journal of Physical Science. XV: 182.

- ^ Pepper, J. H. (1861). The Playbook of Metals: Including Personal Narratives of Visits to Coal, Lead, Copper, and Tin Mines, with a Large Number of Interesting Experiments Relating to Alchemy and the Chemistry of the Fifty Metallic Elements. Routledge, Warne, and Routledge. tr. 455.

- ^ “Radioisotope Brief: Iridium-192 (Ir-192)” (PDF). Radiation Emergencies. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. ngày 18 tháng 8 năm 2004. Truy cập ngày 20 tháng 9 năm 2008.

Liên kết ngoài

| Wikimedia Commons có thêm hình ảnh và phương tiện truyền tải về Iridi. |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn |

| 7 | Fr | Ra | Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Nh | Fl | Mc | Lv | Ts | Og |