Khác biệt giữa bản sửa đổi của “Sinh vật nhân thực”

Không có tóm lược sửa đổi Thẻ: Sửa đổi di động Sửa đổi từ trang di động |

Không có tóm lược sửa đổi Thẻ: Sửa đổi di động Sửa đổi từ trang di động |

||

| Dòng 49: | Dòng 49: | ||

* [[Vật liệu di truyền|Vật chất di truyền]] trong tế bào sinh vật nhân thực thường gồm một hoặc một số phân tử [[DNA]] mạch thẳng, được cô đặc bởi các protein [[histone]] tạo nên cấu trúc [[nhiễm sắc thể]]. Mọi phân tử [[DNA]] được lưu giữ trong [[nhân tế bào]] với một lớp màng nhân bao bọc. Một số bào quan của sinh vật nhân thực có chứa [[DNA]] riêng. |

* [[Vật liệu di truyền|Vật chất di truyền]] trong tế bào sinh vật nhân thực thường gồm một hoặc một số phân tử [[DNA]] mạch thẳng, được cô đặc bởi các protein [[histone]] tạo nên cấu trúc [[nhiễm sắc thể]]. Mọi phân tử [[DNA]] được lưu giữ trong [[nhân tế bào]] với một lớp màng nhân bao bọc. Một số bào quan của sinh vật nhân thực có chứa [[DNA]] riêng. |

||

* Một vài tế bào sinh vật nhân thực có thể di chuyển nhờ [[tiên mao]]. Những tiên mao thường có cấu trúc phức tạp hơn so với [[sinh vật nhân sơ]]. |

* Một vài tế bào sinh vật nhân thực có thể di chuyển nhờ [[tiên mao]]. Những tiên mao thường có cấu trúc phức tạp hơn so với [[sinh vật nhân sơ]]. |

||

{{Đang dịch}} |

|||

==Phát sinh loài<ref name="AdlBass2019">{{cite journal | vauthors = Adl SM, Bass D, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, Agatha S, Berney C, Brown MW, Burki F, Cárdenas P, Čepička I, Chistyakova L, Del Campo J, Dunthorn M, Edvardsen B, Eglit Y, Guillou L, Hampl V, Heiss AA, Hoppenrath M, James TY, Karnkowska A, Karpov S, Kim E, Kolisko M, Kudryavtsev A, Lahr DJ, Lara E, Le Gall L, Lynn DH, Mann DG, Massana R, Mitchell EA, Morrow C, Park JS, Pawlowski JW, Powell MJ, Richter DJ, Rueckert S, Shadwick L, Shimano S, Spiegel FW, Torruella G, Youssef N, Zlatogursky V, Zhang Q | display-authors = 6 | title = Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes | journal = The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology | volume = 66 | issue = 1 | pages = 4–119 | date = January 2019 | pmid = 30257078 | pmc = 6492006 | doi = 10.1111/jeu.12691 }}</ref><ref name="SchönZlatogursky2021">{{cite journal | vauthors = Schön ME, Zlatogursky VV, Singh RP, Poirier C, Wilken S, Mathur V, Strassert JF, Pinhassi J, Worden AZ, Keeling PJ, Ettema TJ | display-authors = 6 |title=Picozoa are archaeplastids without plastid| journal = Nature Communications |year=2021| volume = 12 | issue = 1 |doi=10.1101/2021.04.14.439778|s2cid=233328713| url = http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-189959 }}</ref>== |

|||

{{Clade|{{clade |

|||

|label1=[[Diphoda]] |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Hemimastigophora]] |

|||

| label2=[[Diaphoretickes]] |

|||

| 2={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Cryptista]] |

|||

|label2=[[Archaeplastida]] |

|||

|sublabel2=<small> (+ ''[[Gloeomargarita lithophora]]'') </small> |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

| 1={{clade |

|||

| 1=[[Red algae]] (Rhodophyta) [[File:Bangia.jpg|40 px]] |

|||

| 2=[[Picozoa]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

| 1=[[Glaucophyta]] [[File:Glaucocystis sp.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

| 2=[[Green plants]] (Viridiplantae) [[File:Pediastrum (cropped).jpg|60 px]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| 2={{clade |

|||

| 1={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Haptista]] [[File:Raphidiophrys contractilis.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

|label2=[[TSAR]] |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Telonemia]] |

|||

| label2=[[SAR supergroup|SAR]] |

|||

| 2={{clade |

|||

| label1=[[Halvaria]] |

|||

| 1={{clade |

|||

| 1=[[Stramenopiles]] [[File:Ochromonas.png|40 px]] |

|||

| 2=[[Alveolata]] [[File:Ceratium furca.jpg|80 px]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| 2=[[Rhizaria]] [[File:Ammonia tepida.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|2=''[[Ancoracysta]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| 2=[[Discoba]] (Excavata) [[File:Euglena mutabilis - 400x - 1 (10388739803) (cropped).jpg|55px]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| label2=[[Amorphea]] |

|||

| 2={{clade |

|||

| 1=[[Amoebozoa]] [[File:Chaos carolinensis Wilson 1900.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

|label2=[[Obazoa]] |

|||

| 2={{clade |

|||

| 1=[[Apusomonadida]] [[File:Apusomonas.png|60 px]] |

|||

| label2=[[Opisthokonta]] |

|||

| 2={{clade |

|||

| 1=[[Holomycota]] (inc. fungi) [[File:Asco1013.jpg|60 px]] |

|||

| 2=[[Holozoa]] (inc. animals) [[File:Comb jelly.jpg|45 px]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} }}|label1=Eukaryotes|style1=font-size:80%; line-height:80%}} |

|||

In some analyses, the [[Hacrobia]] group ([[Haptophyta]] + [[Cryptophyta]]) is placed next to [[Archaeplastida]],<ref name="Burki2007">{{cite journal | vauthors = Burki F, Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Minge M, Skjaeveland A, Nikolaev SI, Jakobsen KS, Pawlowski J | title = Phylogenomics reshuffles the eukaryotic supergroups | journal = PLOS ONE| volume = 2 | issue = 8 | pages = e790 | date = August 2007 | pmid = 17726520 | pmc = 1949142 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0000790 | veditors = Butler G | bibcode = 2007PLoSO...2..790B | doi-access = free }}</ref> but in others it is nested inside the Archaeplastida.<ref name=KimGraham2008>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kim E, Graham LE | title = EEF2 analysis challenges the monophyly of Archaeplastida and Chromalveolata | journal = PLOS ONE| volume = 3 | issue = 7 | pages = e2621 | date = July 2008 | pmid = 18612431 | pmc = 2440802 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0002621 | veditors = Redfield RJ | bibcode = 2008PLoSO...3.2621K | doi-access = free }}</ref> However, several recent studies have concluded that Haptophyta and Cryptophyta do not form a monophyletic group.<ref name="BaurBrinPeteRodr10">{{cite journal | vauthors = Baurain D, Brinkmann H, Petersen J, Rodríguez-Ezpeleta N, Stechmann A, Demoulin V, Roger AJ, Burger G, Lang BF, Philippe H | title = Phylogenomic evidence for separate acquisition of plastids in cryptophytes, haptophytes, and stramenopiles | journal = Molecular Biology and Evolution | volume = 27 | issue = 7 | pages = 1698–1709 | date = July 2010 | pmid = 20194427 | doi = 10.1093/molbev/msq059 | doi-access = free }}</ref> The former could be a sister group to the [[SAR supergroup|SAR group]], the latter cluster with the [[Archaeplastida]] (plants in the broad sense).<ref name=Burki2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Burki F, Okamoto N, Pombert JF, Keeling PJ | title = The evolutionary history of haptophytes and cryptophytes: phylogenomic evidence for separate origins | journal = Proceedings: Biological Sciences | volume = 279 | issue = 1736 | pages = 2246–2254 | date = June 2012 | pmid = 22298847 | pmc = 3321700 | doi = 10.1098/rspb.2011.2301 }}</ref> |

|||

The division of the eukaryotes into two primary clades, [[bikonts]] ([[Archaeplastida]] + [[SAR supergroup|SAR]] + [[Excavata]]) and [[unikonts]] ([[Amoebozoa]] + [[Opisthokonta]]), derived from an ancestral biflagellar organism and an ancestral uniflagellar organism, respectively, had been suggested earlier.<ref name="KimGraham2008"/><ref name="CavalierSmith2006">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cavalier-Smith T |s2cid=84403388 | name-list-style = vanc |author-link=Thomas Cavalier-Smith |title=Protist phylogeny and the high-level classification of Protozoa |journal=European Journal of Protistology |year=2006 |volume=39 |issue=4 |pages=338–348 |doi=10.1078/0932-4739-00002}}</ref><ref name="pmid16829542">{{cite journal | vauthors = Burki F, Pawlowski J | title = Monophyly of Rhizaria and multigene phylogeny of unicellular bikonts | journal = Molecular Biology and Evolution | volume = 23 | issue = 10 | pages = 1922–1930 | date = October 2006 | pmid = 16829542 | doi = 10.1093/molbev/msl055 | doi-access = free }}</ref> A 2012 study produced a somewhat similar division, although noting that the terms "unikonts" and "bikonts" were not used in the original sense.<ref name=ZhaoBurkBratKeel12>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zhao S, Burki F, Bråte J, Keeling PJ, Klaveness D, Shalchian-Tabrizi K | title = Collodictyon – an ancient lineage in the tree of eukaryotes | journal = Molecular Biology and Evolution | volume = 29 | issue = 6 | pages = 1557–1568 | date = June 2012 | pmid = 22319147 | pmc = 3351787 | doi = 10.1093/molbev/mss001 | author-link5 = Dag Klaveness (limnologist) }}</ref> |

|||

A highly converged and congruent set of trees appears in Derelle et al. (2015), Ren et al. (2016), Yang et al. (2017) and Cavalier-Smith (2015) including the supplementary information, resulting in a more conservative and consolidated tree. It is combined with some results from Cavalier-Smith for the basal Opimoda.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ren R, Sun Y, Zhao Y, Geiser D, Ma H, Zhou X | title = Phylogenetic Resolution of Deep Eukaryotic and Fungal Relationships Using Highly Conserved Low-Copy Nuclear Genes | journal = Genome Biology and Evolution | volume = 8 | issue = 9 | pages = 2683–2701 | date = September 2016 | pmid = 27604879 | pmc = 5631032 | doi = 10.1093/gbe/evw196 }}</ref><ref name="Cavalier-Smith_2018"/><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Derelle R, Torruella G, Klimeš V, Brinkmann H, Kim E, Vlček Č, Lang BF, Eliáš M | title = Bacterial proteins pinpoint a single eukaryotic root | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 112 | issue = 7 | pages = E693–699 | date = February 2015 | pmid = 25646484 | pmc = 4343179 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.1420657112 | bibcode = 2015PNAS..112E.693D | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yang J, Harding T, Kamikawa R, Simpson AG, Roger AJ | title = Mitochondrial Genome Evolution and a Novel RNA Editing System in Deep-Branching Heteroloboseids | journal = Genome Biology and Evolution | volume = 9 | issue = 5 | pages = 1161–1174 | date = May 2017 | pmid = 28453770 | pmc = 5421314 | doi = 10.1093/gbe/evx086 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cavalier-Smith T, Fiore-Donno AM, Chao E, Kudryavtsev A, Berney C, Snell EA, Lewis R | title = Multigene phylogeny resolves deep branching of Amoebozoa | journal = Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution | volume = 83 | pages = 293–304 | date = February 2015 | pmid = 25150787 | doi = 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.011 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name = "Brown_2018" /><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Torruella G, de Mendoza A, Grau-Bové X, Antó M, Chaplin MA, del Campo J, Eme L, Pérez-Cordón G, Whipps CM, Nichols KM, Paley R, Roger AJ, Sitjà-Bobadilla A, Donachie S, Ruiz-Trillo I | title = Phylogenomics Reveals Convergent Evolution of Lifestyles in Close Relatives of Animals and Fungi | journal = Current Biology | volume = 25 | issue = 18 | pages = 2404–2410 | date = September 2015 | pmid = 26365255 | doi = 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.053 | doi-access = free }}</ref> The main remaining controversies are the root, and the exact positioning of the Rhodophyta and the [[bikont]]s Rhizaria, Haptista, Cryptista, Picozoa and Telonemia, many of which may be endosymbiotic eukaryote-eukaryote hybrids.<ref name="López-García_2017"/> Archaeplastida acquired [[chloroplast]]s probably by endosymbiosis of a prokaryotic ancestor related to a currently extant [[Cyanobacteria|cyanobacterium]], ''[[Gloeomargarita lithophora]]''.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ponce-Toledo RI, Deschamps P, López-García P, Zivanovic Y, Benzerara K, Moreira D | title = An Early-Branching Freshwater Cyanobacterium at the Origin of Plastids | journal = Current Biology | volume = 27 | issue = 3 | pages = 386–391 | date = February 2017 | pmid = 28132810 | pmc = 5650054 | doi = 10.1016/j.cub.2016.11.056 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = de Vries J, Archibald JM | title = Endosymbiosis: Did Plastids Evolve from a Freshwater Cyanobacterium? | journal = Current Biology | volume = 27 | issue = 3 | pages = R103–105 | date = February 2017 | pmid = 28171752 | doi = 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.006 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="López-García_2017">{{cite journal | vauthors = López-García P, Eme L, Moreira D | title = Symbiosis in eukaryotic evolution | journal = Journal of Theoretical Biology | volume = 434 | pages = 20–33 | date = December 2017 | pmid = 28254477 | pmc = 5638015 | doi = 10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.02.031 | bibcode = 2017JThBi.434...20L }}</ref> |

|||

{{Clade|{{clade |

|||

|label1=[[Diphoda]] |

|||

|1={{Clade |

|||

|2=[[Hemimastigophora]] |

|||

|3=[[Discoba]] |

|||

|label1=[[Diaphoretickes]] |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|label1=[[Archaeplastida]] |sublabel1=<small> (+ ''[[Gloeomargarita lithophora]]'') </small> |

|||

|1={{Clade |

|||

| 1=[[Glaucophyta]] |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Rhodophyta]] |

|||

| 2=[[Viridiplantae]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|label2=[[Hacrobia]] |

|||

| 2={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Haptista]] |

|||

| 2=[[Cryptista]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| label2=[[SAR supergroup|SAR]] |

|||

| 2={{clade |

|||

|label1=[[Halvaria]] |

|||

| 1={{clade |

|||

| 1=[[Stramenopiles]] |

|||

| 2=[[Alveolata]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| 2=[[Rhizaria]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|label2=[[Opimoda]] |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Loukozoa]] |

|||

| label2=[[Podiata]] |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|label1=[[CRuMs]] |

|||

|1=[[Varisulca|Diphyllatea]], [[Rigifilida]], [[Varisulca|Mantamonas]] |

|||

|label2=[[Amorphea]] |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

| 1=[[Amoebozoa]] |

|||

|label2=[[Obazoa]] |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Breviata]] |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Apusomonadida]] |

|||

| 2=[[Opisthokonta]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} }}}}}}}}}}}}|style=font-size:80%; line-height:80%|label1=Eukaryotes}} |

|||

==== Cavalier-Smith's tree ==== |

|||

[[Thomas Cavalier-Smith]] 2010,<ref name="Cavalier-Smith2010b">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cavalier-Smith T | title = Kingdoms Protozoa and Chromista and the eozoan root of the eukaryotic tree | journal = Biology Letters | volume = 6 | issue = 3 | pages = 342–345 | date = June 2010 | pmid = 20031978 | pmc = 2880060 | doi = 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0948 }}</ref> 2013,<ref name="Cavalier-Smith2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cavalier-Smith T | title = Early evolution of eukaryote feeding modes, cell structural diversity, and classification of the protozoan phyla Loukozoa, Sulcozoa, and Choanozoa | journal = European Journal of Protistology | volume = 49 | issue = 2 | pages = 115–178 | date = May 2013 | pmid = 23085100 | doi = 10.1016/j.ejop.2012.06.001}}</ref> 2014,<ref name="cavalier2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE, Snell EA, Berney C, Fiore-Donno AM, Lewis R | title = Multigene eukaryote phylogeny reveals the likely protozoan ancestors of opisthokonts (animals, fungi, choanozoans) and Amoebozoa | journal = Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution | volume = 81 | pages = 71–85 | date = December 2014 | pmid = 25152275 | doi = 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.012 | doi-access = free }}</ref> 2017<ref name="Cavalier-Smith_2018">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cavalier-Smith T | title = Kingdom Chromista and its eight phyla: a new synthesis emphasising periplastid protein targeting, cytoskeletal and periplastid evolution, and ancient divergences | journal = Protoplasma | volume = 255 | issue = 1 | pages = 297–357 | date = January 2018 | pmid = 28875267 | pmc = 5756292 | doi = 10.1007/s00709-017-1147-3 }}</ref> and 2018<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE, Lewis R | title = Multigene phylogeny and cell evolution of chromist infrakingdom Rhizaria: contrasting cell organisation of sister phyla Cercozoa and Retaria | journal = Protoplasma | volume = 255 | issue = 5 | pages = 1517–1574 | date = April 2018 | pmid = 29666938 | pmc = 6133090 | doi = 10.1007/s00709-018-1241-1 }}</ref> places the eukaryotic tree's root between [[Excavata]] (with ventral feeding groove supported by a microtubular root) and the grooveless [[Euglenozoa]], and monophyletic Chromista, correlated to a single endosymbiotic event of capturing a red-algae. He et al.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = He D, Fiz-Palacios O, Fu CJ, Fehling J, Tsai CC, Baldauf SL | title = An alternative root for the eukaryote tree of life | journal = Current Biology | volume = 24 | issue = 4 | pages = 465–470 | date = February 2014 | pmid = 24508168 | doi = 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.036 | doi-access = free }}</ref> specifically supports rooting the eukaryotic tree between a monophyletic [[Discoba]] ([[Discicristata]] + [[Jakobidae|Jakobida]]) and an [[Amorphea]]-[[Diaphoretickes]] clade. |

|||

{{Clade |

|||

|style= font-size:80%; line-height:80% |

|||

|label1=Eukaryotes |

|||

|1={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Euglenozoa]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Percolozoa]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|label1=[[Eolouka]] |

|||

|1={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Tsukubea|''Tsukubamonas globosa'']] |

|||

|2=[[Jakobea]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|label2=[[Neokaryotes|Neokaryota]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|label1=[[Corticata]] |

|||

|1={{Clade |

|||

|label1=[[Archaeplastida]] |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Glaucophytes]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Rhodophytes]] |

|||

|2=[[Viridiplantae]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|label2=[[Chromista]] |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Hacrobia]] |

|||

|2=[[SAR supergroup|SAR]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|label2=[[Scotokaryotes|Scotokaryota]] |

|||

|sublabel2=[[Opimoda]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Malawimonadea|''Malawimonas'']] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Metamonada]] |

|||

|label2=[[Podiata]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Ancyromonadida]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Mantamonadidae|''Mantamonas plastica'']] |

|||

|2=[[Varisulca|Diphyllatea]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|label2=[[Amorphea]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Amoebozoa]] |

|||

|label2=[[Obazoa]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Breviatea]] |

|||

|2={{Clade |

|||

|1=[[Apusomonadida]] |

|||

|2=[[Opisthokonta]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

== Xem thêm == |

== Xem thêm == |

||

Phiên bản lúc 04:41, ngày 10 tháng 1 năm 2022

Bài viết này cần thêm chú thích nguồn gốc để kiểm chứng thông tin. |

| Sinh vật nhân thực | |

|---|---|

| Thời điểm hóa thạch: Liên đại Nguyên sinh - gần đây | |

Ostreococcus - Sinh vật nhân thực nhỏ nhất được ghi nhận còn tồn tại với đường kính cỡ 0,8 µm. | |

| Phân loại khoa học | |

| Liên vực (superdomain) | Neomura |

| Vực (domain) | Eukarya/Eukaryota Whittaker & Margulis,1978 |

| Giới[2] | |

Danh sách

| |

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

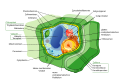

Sinh vật nhân thực, còn gọi là sinh vật nhân chuẩn, sinh vật nhân điển hình hoặc sinh vật có nhân chính thức (danh pháp: Eukaryota hay Eukarya)[3] là một sinh vật gồm các tế bào phức tạp, trong đó vật liệu di truyền được sắp đặt trong nhân có màng bao bọc. Eukaryote là chữ Latin có nghĩa là có nhân thật sự.

Sinh vật nhân thực gồm có động vật, thực vật và nấm - hầu hết chúng là sinh vật đa bào - cũng như các nhóm đa dạng khác được gọi chung là nguyên sinh vật (đa số là sinh vật đơn bào, bao gồm động vật nguyên sinh và thực vật nguyên sinh). Trái lại, các sinh vật khác, chẳng hạn như vi khuẩn, không có nhân và các cấu trúc tế bào phức tạp khác; những sinh vật như thế được gọi là sinh vật tiền nhân hoặc sinh vật nhân sơ (prokaryote). Sinh vật nhân thực có cùng một nguồn gốc và thường được xếp thành một siêu giới hoặc vực (domain).

Các sinh vật này thường lớn gấp 10 lần (về kích thước) so với sinh vật nhân sơ, do đó gấp khoảng 1000 lần về thể tích. Điểm khác biệt quan trọng giữa sinh vật nhân sơ và sinh vật nhân thực là tế bào nhân thực có các xoang tế bào được chia nhỏ do các lớp màng tế bào để thực hiện các hoạt động trao đổi chất riêng biệt. Trong đó, điều tiến bộ nhất là việc hình thành nhân tế bào có hệ thống màng riêng để bảo vệ các phân tử DNA (?) của tế bào. Tế bào sinh vật nhân thực thường có những cấu trúc chuyên biệt để tiến hành các chức năng nhất định, gọi là các bào quan. Các đặc trưng gồm:

- Tế bào chất của sinh vật nhân thực thường không nhìn thấy những thể hạt như ở sinh vật nhân sơ vì rằng phần lớn ribosome của chúng được bám trên mạng lưới nội chất.

- Màng tế bào cũng có cấu trúc tương tự như ở sinh vật nhân sơ tuy nhiên thành phần cấu tạo chi tiết lại khác nhau một vài điểm nhỏ. Chỉ một số tế bào sinh vật nhân thực có thành tế bào.

- Vật chất di truyền trong tế bào sinh vật nhân thực thường gồm một hoặc một số phân tử DNA mạch thẳng, được cô đặc bởi các protein histone tạo nên cấu trúc nhiễm sắc thể. Mọi phân tử DNA được lưu giữ trong nhân tế bào với một lớp màng nhân bao bọc. Một số bào quan của sinh vật nhân thực có chứa DNA riêng.

- Một vài tế bào sinh vật nhân thực có thể di chuyển nhờ tiên mao. Những tiên mao thường có cấu trúc phức tạp hơn so với sinh vật nhân sơ.

Bài viết này là công việc biên dịch đang được tiến hành từ bài viết ArticleName từ một ngôn ngữ khác sang tiếng Việt. Bạn có thể giúp Wikipedia bằng cách hỗ trợ dịch và trau chuốt lối hành văn tiếng Việt theo cẩm nang của Wikipedia. |

Phát sinh loài[4][5]

| Eukaryotes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In some analyses, the Hacrobia group (Haptophyta + Cryptophyta) is placed next to Archaeplastida,[6] but in others it is nested inside the Archaeplastida.[7] However, several recent studies have concluded that Haptophyta and Cryptophyta do not form a monophyletic group.[8] The former could be a sister group to the SAR group, the latter cluster with the Archaeplastida (plants in the broad sense).[9]

The division of the eukaryotes into two primary clades, bikonts (Archaeplastida + SAR + Excavata) and unikonts (Amoebozoa + Opisthokonta), derived from an ancestral biflagellar organism and an ancestral uniflagellar organism, respectively, had been suggested earlier.[7][10][11] A 2012 study produced a somewhat similar division, although noting that the terms "unikonts" and "bikonts" were not used in the original sense.[12]

A highly converged and congruent set of trees appears in Derelle et al. (2015), Ren et al. (2016), Yang et al. (2017) and Cavalier-Smith (2015) including the supplementary information, resulting in a more conservative and consolidated tree. It is combined with some results from Cavalier-Smith for the basal Opimoda.[13][14][15][16][17][18][19] The main remaining controversies are the root, and the exact positioning of the Rhodophyta and the bikonts Rhizaria, Haptista, Cryptista, Picozoa and Telonemia, many of which may be endosymbiotic eukaryote-eukaryote hybrids.[20] Archaeplastida acquired chloroplasts probably by endosymbiosis of a prokaryotic ancestor related to a currently extant cyanobacterium, Gloeomargarita lithophora.[21][22][20]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

}}|style=font-size:80%; line-height:80%|label1=Eukaryotes}}

Cavalier-Smith's tree

Thomas Cavalier-Smith 2010,[23] 2013,[24] 2014,[25] 2017[14] and 2018[26] places the eukaryotic tree's root between Excavata (with ventral feeding groove supported by a microtubular root) and the grooveless Euglenozoa, and monophyletic Chromista, correlated to a single endosymbiotic event of capturing a red-algae. He et al.[27] specifically supports rooting the eukaryotic tree between a monophyletic Discoba (Discicristata + Jakobida) and an Amorphea-Diaphoretickes clade.

| Eukaryotes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Xem thêm

Hình ảnh

Tham khảo

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, T. 2009: Megaphylogeny, cell body plans, adaptive zones: causes and timing of eukaryote basal radiations. Journal of eukaryotic microbiology, 56: 26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00373.x

- ^ Adl, S.M. et al. 2005: The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists. Journal of eukaryotic microbiology, 52: 399–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.

- ^ “Eukaryota.Uniprot.org(Taxonomy 2759)”.

- ^ Adl SM, Bass D, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, và đồng nghiệp (tháng 1 năm 2019). “Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes”. The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ Schön ME, Zlatogursky VV, Singh RP, Poirier C, Wilken S, Mathur V, và đồng nghiệp (2021). “Picozoa are archaeplastids without plastid”. Nature Communications. 12 (1). doi:10.1101/2021.04.14.439778. S2CID 233328713.

- ^ Burki F, Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Minge M, Skjaeveland A, Nikolaev SI, Jakobsen KS, Pawlowski J (tháng 8 năm 2007). Butler G (biên tập). “Phylogenomics reshuffles the eukaryotic supergroups”. PLOS ONE. 2 (8): e790. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..790B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000790. PMC 1949142. PMID 17726520.

- ^ a b Kim E, Graham LE (tháng 7 năm 2008). Redfield RJ (biên tập). “EEF2 analysis challenges the monophyly of Archaeplastida and Chromalveolata”. PLOS ONE. 3 (7): e2621. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2621K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002621. PMC 2440802. PMID 18612431.

- ^ Baurain D, Brinkmann H, Petersen J, Rodríguez-Ezpeleta N, Stechmann A, Demoulin V, Roger AJ, Burger G, Lang BF, Philippe H (tháng 7 năm 2010). “Phylogenomic evidence for separate acquisition of plastids in cryptophytes, haptophytes, and stramenopiles”. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 27 (7): 1698–1709. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq059. PMID 20194427.

- ^ Burki F, Okamoto N, Pombert JF, Keeling PJ (tháng 6 năm 2012). “The evolutionary history of haptophytes and cryptophytes: phylogenomic evidence for separate origins”. Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 279 (1736): 2246–2254. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.2301. PMC 3321700. PMID 22298847.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (2006). “Protist phylogeny and the high-level classification of Protozoa”. European Journal of Protistology. 39 (4): 338–348. doi:10.1078/0932-4739-00002. S2CID 84403388.

- ^ Burki F, Pawlowski J (tháng 10 năm 2006). “Monophyly of Rhizaria and multigene phylogeny of unicellular bikonts”. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (10): 1922–1930. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl055. PMID 16829542.

- ^ Zhao S, Burki F, Bråte J, Keeling PJ, Klaveness D, Shalchian-Tabrizi K (tháng 6 năm 2012). “Collodictyon – an ancient lineage in the tree of eukaryotes”. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (6): 1557–1568. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss001. PMC 3351787. PMID 22319147.

- ^ Ren R, Sun Y, Zhao Y, Geiser D, Ma H, Zhou X (tháng 9 năm 2016). “Phylogenetic Resolution of Deep Eukaryotic and Fungal Relationships Using Highly Conserved Low-Copy Nuclear Genes”. Genome Biology and Evolution. 8 (9): 2683–2701. doi:10.1093/gbe/evw196. PMC 5631032. PMID 27604879.

- ^ a b Cavalier-Smith T (tháng 1 năm 2018). “Kingdom Chromista and its eight phyla: a new synthesis emphasising periplastid protein targeting, cytoskeletal and periplastid evolution, and ancient divergences”. Protoplasma. 255 (1): 297–357. doi:10.1007/s00709-017-1147-3. PMC 5756292. PMID 28875267.

- ^ Derelle R, Torruella G, Klimeš V, Brinkmann H, Kim E, Vlček Č, Lang BF, Eliáš M (tháng 2 năm 2015). “Bacterial proteins pinpoint a single eukaryotic root”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (7): E693–699. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112E.693D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420657112. PMC 4343179. PMID 25646484.

- ^ Yang J, Harding T, Kamikawa R, Simpson AG, Roger AJ (tháng 5 năm 2017). “Mitochondrial Genome Evolution and a Novel RNA Editing System in Deep-Branching Heteroloboseids”. Genome Biology and Evolution. 9 (5): 1161–1174. doi:10.1093/gbe/evx086. PMC 5421314. PMID 28453770.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T, Fiore-Donno AM, Chao E, Kudryavtsev A, Berney C, Snell EA, Lewis R (tháng 2 năm 2015). “Multigene phylogeny resolves deep branching of Amoebozoa”. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 83: 293–304. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.011. PMID 25150787.

- ^ Lỗi chú thích: Thẻ

<ref>sai; không có nội dung trong thẻ ref có tênBrown_2018 - ^ Torruella G, de Mendoza A, Grau-Bové X, Antó M, Chaplin MA, del Campo J, Eme L, Pérez-Cordón G, Whipps CM, Nichols KM, Paley R, Roger AJ, Sitjà-Bobadilla A, Donachie S, Ruiz-Trillo I (tháng 9 năm 2015). “Phylogenomics Reveals Convergent Evolution of Lifestyles in Close Relatives of Animals and Fungi”. Current Biology. 25 (18): 2404–2410. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.053. PMID 26365255.

- ^ a b López-García P, Eme L, Moreira D (tháng 12 năm 2017). “Symbiosis in eukaryotic evolution”. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 434: 20–33. Bibcode:2017JThBi.434...20L. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.02.031. PMC 5638015. PMID 28254477.

- ^ Ponce-Toledo RI, Deschamps P, López-García P, Zivanovic Y, Benzerara K, Moreira D (tháng 2 năm 2017). “An Early-Branching Freshwater Cyanobacterium at the Origin of Plastids”. Current Biology. 27 (3): 386–391. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.11.056. PMC 5650054. PMID 28132810.

- ^ de Vries J, Archibald JM (tháng 2 năm 2017). “Endosymbiosis: Did Plastids Evolve from a Freshwater Cyanobacterium?”. Current Biology. 27 (3): R103–105. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.006. PMID 28171752.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (tháng 6 năm 2010). “Kingdoms Protozoa and Chromista and the eozoan root of the eukaryotic tree”. Biology Letters. 6 (3): 342–345. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0948. PMC 2880060. PMID 20031978.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (tháng 5 năm 2013). “Early evolution of eukaryote feeding modes, cell structural diversity, and classification of the protozoan phyla Loukozoa, Sulcozoa, and Choanozoa”. European Journal of Protistology. 49 (2): 115–178. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2012.06.001. PMID 23085100.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE, Snell EA, Berney C, Fiore-Donno AM, Lewis R (tháng 12 năm 2014). “Multigene eukaryote phylogeny reveals the likely protozoan ancestors of opisthokonts (animals, fungi, choanozoans) and Amoebozoa”. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 81: 71–85. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.012. PMID 25152275.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE, Lewis R (tháng 4 năm 2018). “Multigene phylogeny and cell evolution of chromist infrakingdom Rhizaria: contrasting cell organisation of sister phyla Cercozoa and Retaria”. Protoplasma. 255 (5): 1517–1574. doi:10.1007/s00709-018-1241-1. PMC 6133090. PMID 29666938.

- ^ He D, Fiz-Palacios O, Fu CJ, Fehling J, Tsai CC, Baldauf SL (tháng 2 năm 2014). “An alternative root for the eukaryote tree of life”. Current Biology. 24 (4): 465–470. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.036. PMID 24508168.

Liên kết ngoài

Dữ liệu liên quan tới Eukaryota tại Wikispecies

Dữ liệu liên quan tới Eukaryota tại Wikispecies Tư liệu liên quan tới Eukaryota tại Wikimedia Commons

Tư liệu liên quan tới Eukaryota tại Wikimedia Commons- Eukaryote tại Encyclopædia Britannica (tiếng Anh)

- Eukaryotes (Tree of Life web site)

- Prokaryote versus eukaryote, BioMineWiki