Khác biệt giữa bản sửa đổi của “Mặt Trăng”

nKhông có tóm lược sửa đổi |

|||

| Dòng 288: | Dòng 288: | ||

Ban ngày trên Mặt trăng, nhiệt độ trung bình là 107°C, còn ban đêm nhiệt độ là -153°C.<ref>[http://www.asi.org/adb/m/03/05/average-temperatures.html Artemis Project: Lunar Surface Temperatures<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

Ban ngày trên Mặt trăng, nhiệt độ trung bình là 107°C, còn ban đêm nhiệt độ là -153°C.<ref>[http://www.asi.org/adb/m/03/05/average-temperatures.html Artemis Project: Lunar Surface Temperatures<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

==Origin and geologic evolution== |

|||

== Quỹ đạo == |

|||

=== |

===Formation=== |

||

[[Image:The Moon Luc Viatour.jpg|right|thumb]] |

|||

Mặt Trăng quay quanh Trái Đất trên một [[quỹ đạo]] gần như một [[quỹ đạo tròn]]. Nó cần khoảng một [[tháng]] để quay một vòng quanh quỹ đạo. Mỗi [[giờ]], Mặt Trăng di chuyển so với nền [[sao]] một [[cung]] có độ lớn xấp xỉ bằng [[đường kính góc]] của nó tức là khoảng 0,5[[độ (góc)|°]]. |

|||

Several mechanisms have been suggested for the Moon's formation. The formation of the Moon is believed to have occurred 4.527 ± 0.010 billion years ago, about 30–50 million years after the origin of the Solar System.<ref>{{cite journal |doi= 10.1126/science.1118842 |journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |date=2005 |volume=310 |issue=5754 |pages=1671–1674 |title=Hf–W Chronometry of Lunar Metals and the Age and Early Differentiation of the Moon |last=Kleine |first=T. |coauthors=Palme, H.; Mezger, K.; Halliday, A.N. |accessdate=2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

Khi nhìn từ [[cực Bắc]] xuống, Trái Đất và Mặt Trăng quay quanh [[khối tâm]] của hệ, một điểm cách tâm Trái Đất chỉ 4700 [[kilômét|km]], [[ngược chiều kim đồng hồ]], cùng chiều với chiều quay của Trái Đất quanh Mặt Trời. |

|||

; [[Fission]] theory : Early speculation proposed that the Moon broke off from the Earth's crust because of [[centrifugal force]]s, leaving a basin{{ndash}} presumed to be the [[Pacific Ocean]]{{ndash}} behind as a scar.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Binder |first=A.B. |title=On the origin of the moon by rotational fission |journal=The Moon |date=1974 |volume=11 |issue=2 |pages=53–76 |url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1974Moon...11...53B |accessdate=2007-04-12}}</ref> This idea, however, would require too great an initial spin of the Earth; and, even had this been possible, the process should have resulted in the Moon's orbit following Earth's [[Celestial sphere|equatorial plane]]. This is not the case. |

|||

{| cellspacing=0 cellpadding=0 |

|||

| [[Hình:Moon PIA00302.jpg|nhỏ|200px|Nửa nhìn thấy từ Trái Đất của Mặt Trăng.]] |

|||

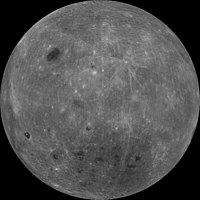

| [[Hình:Moon PIA00304.jpg|nhỏ|200px|Nửa không nhìn thấy từ Trái Đất của Mặt Trăng.]] |

|||

|} |

|||

; Capture theory : Other speculation has centered on the Moon being formed elsewhere and subsequently being captured by Earth's gravity.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Mitler |first=H.E. |title=Formation of an iron-poor moon by partial capture, or: Yet another exotic theory of lunar origin |journal=[[Icarus (journal)|Icarus]] |date=1975 |volume=24 |pages=256–268 |url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1975Icar...24..256M |accessdate=2007-04-12}}</ref> However, the conditions believed necessary for such a mechanism to work, such as an [[Earth's atmosphere|extended atmosphere of the Earth]] in order to [[Dissipation|dissipate]] the energy of the passing Moon, are improbable. |

|||

Khác với hầu hết các [[vệ tinh tự nhiên]] của các [[hành tinh]] khác trong [[hệ Mặt Trời]], Mặt Trăng có [[mặt phẳng quỹ đạo]] nằm gần với [[mặt phẳng hoàng đạo]] chứ không gần [[mặt phẳng xích đạo]] của hành tinh ([[Trái Đất]]). Mặt phẳng quỹ đạo của [[Mặt Trăng]] nghiêng khoảng 5° so với mặt phẳng hoàng đạo. Giao điểm của hai mặt phẳng này trên [[thiên cầu]] là 2 điểm [[nút mặt trăng]]. |

|||

; Co-formation theory : The co-formation hypothesis proposes that the Earth and the Moon formed together at the same time and place from the primordial [[accretion disk]]. The Moon would have formed from material surrounding the proto-Earth, similar to the formation of the planets around the Sun. Some suggest that this hypothesis fails adequately to explain the depletion of metallic iron in the Moon. |

|||

Hiện tượng [[nhật thực]] và [[nguyệt thực]] chỉ xảy ra khi Trái Đất, Mặt Trăng và Mặt Trời thẳng hàng. |

|||

A major deficiency in all these hypotheses is that they cannot readily account for the high [[angular momentum]] of the Earth–Moon system.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Stevenson |first=D.J. |title=Origin of the moon – The collision hypothesis |journal=Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences |date=1987 |volume=15 |pages=271–315 |url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1987AREPS..15..271S |accessdate=2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

*'''Nhật thực''' xảy ra khi Mặt Trăng nằm giữa Trái Đất và Mặt Trời. Lúc đó Mặt Trăng trên mặt phẳng hoàng đạo, tại một trong hai điểm nút mặt trăng, đồng thời ở vào [[pha trăng mới]] ([[mồng một]] [[âm lịch]], hay [[sóc (lịch)|sóc lịch]]). |

|||

{{main|Nhật thực}} |

|||

*'''Nguyệt thực''' xảy ra khi Trái Đất nằm giữa Mặt Trời và Mặt Trăng. Lúc đó Mặt Trăng trên mặt phẳng hoàng đạo, tại một trong hai điểm nút mặt trăng, đồng thời ở vào [[pha trăng tròn]] ([[rằm]] âm lịch). |

|||

{{main|Nguyệt thực}} |

|||

; Giant Impact theory : The prevailing hypothesis today is that the Earth–Moon system formed as a result of a [[Giant impact hypothesis|giant impact]]. A Mars-sized body (labelled "Theia") is believed to have hit the proto-Earth, blasting sufficient material into orbit around the proto-Earth to form the Moon through accretion.<ref name="worldbook"/> As accretion is the process by which all planetary bodies are believed to have formed, giant impacts are thought to have affected most if not all planets. Computer simulations modelling a giant impact are consistent with measurements of the [[angular momentum]] of the Earth–Moon system, as well as the small size of the lunar core.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Canup |first=R. |coauthors=Asphaug, E. |title=Origin of the Moon in a giant impact near the end of the Earth's formation |journal=Nature |volume=412 |pages=708–712 |date=2001}}</ref> Unresolved questions regarding this theory concern the determination of the relative sizes of the proto-Earth and Theia and of how much material from these two bodies formed the Moon. |

|||

===Biến đổi theo thời gian=== |

|||

===Lunar magma ocean=== |

|||

Các [[tham số quỹ đạo]] của Mặt Trăng thay đổi chậm theo thời gian, chủ yếu do tác động của lực [[thủy triều]] giữa Mặt Trăng và Trái Đất. Lực hấp dẫn của Mặt Trăng bóp méo [[thủy quyển]] trên Trái Đất, gây ra thủy triều. Chu kỳ lên xuống của thủy triều trùng với chu kỳ Mặt Trăng quay quanh Trái Đất, nhưng thủy triều bị [[trễ pha]] so với Mặt Trăng. Sự trễ pha này gây ra bởi việc Trái Đất tự quay quanh trục, và bề mặt cứng của nó gây [[ma sát]] cho thủy quyển. Kết quả là, một phần [[mômen động lượng]] tự quay của Trái Đất được chuyển dần sang cho mômen động lượng quỹ đạo của Mặt Trăng. Mặt Trăng dần đi xa ra khỏi Trái Đất, tốc độ ra xa hiện nay khoảng 38 [[milimét|mm]] một năm. Đồng thời Trái Đất cũng quay chậm lại, ngày trên Trái Đất sẽ dài thêm ra 15 [[micrôgiây|µs]] mỗi năm. |

|||

As a result of the large amount of energy liberated during both the giant impact event and the subsequent reaccretion of material in Earth orbit, it is commonly believed that a large portion of the Moon was once initially molten. The molten outer portion of the Moon at this time is referred to as a [[lunar magma ocean|magma ocean]], and estimates for its depth range from about 500 km to the entire radius of the Moon.<ref name="S06"/> |

|||

As the magma ocean cooled, it fractionally crystallised and [[planetary differentiation|differentiated]], giving rise to a geochemically distinct crust and mantle. The mantle is inferred to have formed largely by the precipitation and sinking of the minerals [[olivine]], [[clinopyroxene]], and [[orthopyroxene]]. After about three-quarters of magma ocean crystallisation was complete, the mineral [[anorthite]] is inferred to have precipitated and floated to the surface because of its low density, forming the crust.<ref name="S06"/> |

|||

Lực thủy triều trong quá khứ cũng đã làm chậm chuyển động tự quay của Mặt Trăng lại. Đến ngày nay, tốc độ tự quay này đã chậm lại đến một giá trị cân bằng đặc biệt, khiến Mặt Trăng đi vào trạng thái [[quay đồng bộ]], tức là luôn hướng một mặt về Trái Đất: [[tốc độ góc]] tự quay đúng bằng tốc độ góc quay trên quỹ đạo. |

|||

The final liquids to crystallise from the magma ocean would have been initially sandwiched between the crust and mantle, and would have contained a high abundance of incompatible and heat-producing elements. This geochemical component is referred to by the acronym [[KREEP]], for [[potassium]] (K), [[rare earth elements]] (REE), and [[phosphorus]] (P), and appears to be concentrated within the [[lunar terranes|Procellarum KREEP Terrane]], which is a small geologic province that encompasses most of [[Oceanus Procellarum]] and [[Mare Imbrium]] on the near side of the Moon.<ref name="W06"/> |

|||

Thực ra quỹ đạo Mặt Trăng không [[đường tròn|tròn]] tuyệt đối (có [[độ lệch tâm]] dương) và việc nói Mặt Trăng luôn quay một mặt về phía Trái Đất cũng là gần đúng. Mặt Trăng, như mọi vật chuyển động trên quỹ đạo Kepler, chuyển động nhanh hơn ở [[cận điểm quỹ đạo]] và chậm hơn ở [[viễn điểm quỹ đạo]]. Điều này giúp ta thấy thêm khoảng 8 [[kinh độ]] mặt ''bên kia'' của Mặt Trăng. Ngoài ra, quỹ đạo Mặt Trăng cũng nghiêng so với mặt phẳng xích đạo của Trái Đất, nên ta cũng thấy thêm 7 [[vĩ độ]] mặt bên kia. Cuối cùng, Mặt Trăng nằm đủ gần để một người quan sát ở [[xích đạo]] suốt một đêm, sau khi di chuyển khoảng cách bằng [[đường kính]] Trái Đất nhờ sự tự quay của Trái Đất, nhìn được thêm 1 kinh độ mặt bên kia. |

|||

== |

===Geologic evolution=== |

||

{{seealso|Geology of the Moon}} |

|||

[[Hình:Moon_Schematic_Cross_Section.png|nhỏ|trái|300px|Mô phỏng cấu trúc Mặt Trăng.]] |

|||

A large portion of the Moon's post–magma-ocean geologic evolution was dominated by impact cratering. The [[lunar geologic timescale]] is largely divided in time on the basis of prominent basin-forming impact events, such as [[Nectarian|Nectaris]], [[Lower Imbrian|Imbrium]], and [[Mare Orientale|Orientale]]. These impact structures are characterised by multiple rings of uplifted material, and are typically hundreds to thousands of kilometres in diameter. Each multi-ring basin is associated with a broad apron of ejecta deposits that forms a regional stratigraphic horizon. While only a few multi-ring basins have been definitively dated, they are useful for assigning relative ages on the basis of [[Stratigraphy|stratigraphic]] grounds. The continuous effects of impact cratering are responsible for forming the [[regolith]]. |

|||

The other major geologic process that affected the Moon's surface was [[lunar mare|mare volcanism]]. The enhancement of heat-producing elements within the [[lunar terranes|Procellarum KREEP Terrane]] is thought to have caused the underlying mantle to heat up, and eventually, to partially melt. A portion of these magmas rose to the surface and erupted, accounting for the high concentration of mare basalts on the near side of the Moon.<ref name="S06"/> Most of the Moon's [[lunar mare|mare basalts]] erupted during the Imbrian period in this geologic province 3.0–3.5 billion years ago. Nevertheless, some dated samples are as old as 4.2 billion years,<ref name = "Papike">{{cite journal | last = Papike | first = J. | coauthors = Ryder, G.; Shearer, C. | title = Lunar Samples | journal = Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry | volume = 36 | pages = 5.1–5.234 | date = 1998}}</ref> and the youngest eruptions, based on the method of [[crater counting]], are believed to have occurred only 1.2 billion years ago.<ref name = "Hiesinger">{{cite journal | last = Hiesinger | first = H. | coauthors = Head, J.W.; Wolf, U.; Jaumanm, R.; Neukum, G. | title = Ages and stratigraphy of mare basalts in Oceanus Procellarum, Mare Numbium, Mare Cognitum, and Mare Insularum | journal = J. Geophys. Res. | volume = 108 | pages = 1029 | date = 2003}}</ref> |

|||

===Khí quyển=== |

|||

Mặt Trăng có bầu [[khí quyển]] cực mỏng. Nguồn chính tạo các [[phân tử]] lơ lửng trên bề mặt là sự thải ra chất khí từ đất đá bên trong lòng, như [[radon]]. Một nguồn khác là [[gió mặt trời]], bị bắt tạm thời bởi [[trọng trường]] của Mặt Trăng. Các khí từ nguồn này không tồn tại lâu trên bề mặt Mặt Trăng mà thoát ra dần dần. Khi bề mặt Mặt Trăng tiếp xúc với [[ánh nắng]] Mặt Trời, [[nhiệt độ]] tăng lên đến chừng vài chục [[độ C]], đủ để cung cấp cho các phân tử khí [[tốc độ]] trung bình của [[chuyển động nhiệt]] lớn hơn [[tốc độ vũ trụ cấp 2]] của Mặt Trăng, vốn nhỏ do trọng trường yếu của thiên thể, và các chất khí thoát khỏi Mặt Trăng vĩnh viễn. |

|||

There has been controversy over whether features on the Moon's surface undergo changes over time. Some observers have claimed that craters either appeared or disappeared, or that other forms of transient phenomena had occurred. Today, many of these claims are thought to be illusory, resulting from observation under different lighting conditions, poor [[astronomical seeing]], or the inadequacy of earlier drawings. Nevertheless, it is known that the phenomenon of [[outgassing]] does occasionally occur, and these events could be responsible for a minor percentage of the reported [[transient lunar phenomenon|lunar transient phenomena]]. Recently, it has been suggested that a roughly 3 km diameter region of the lunar surface was modified by a gas release event about a million years ago.<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/Nov06/MoonGas.html | last = Taylor | first = G.J. | title = Recent Gas Escape from the Moon | publisher = Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology | date = [[2006-11-08]] | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last = Schultz | first = P.H. | coauthors = Staid, M.I.; Pieters, C.M. | date = 2006 | title = Lunar activity from recent gas release | journal= Nature |volume = 444 |pages = 184–186}}</ref> |

|||

Do gần như không có bầu khí quyển, trên Mặt Trăng không có các hiện tượng khí tượng như [[gió]], [[bão]] hay sự xói mòn bề mặt. Các vị trí trên bề mặt của Mặt Trăng hầu như giữ được trạng thái nguyên thủy của nó cho đến khi bị một [[thiên thạch]] bắn phá. |

|||

=== |

===Moon rocks=== |

||

{{main| |

{{main|Moon rocks}} |

||

Moon rocks fall into two main categories, based on whether they underlie the lunar highlands (terrae) or the maria. The lunar highlands rocks are composed of three suites: the ''ferroan anorthosite suite'', the ''magnesian suite'', and the ''alkali suite'' (some consider the alkali suite to be a subset of the mg-suite). The ferroan anorthosite suite rocks are composed almost exclusively of the mineral [[anorthite]] (a calic [[plagioclase feldspar]]), and are believed to represent plagioclase flotation cumulates of the lunar magma ocean. The ferroan anorthosites have been dated using radiometric methods to have formed about 4.4 billion years ago.<ref name = "Papike" /><ref name = "Hiesinger" /> |

|||

[[Hình:MoonTopoGeoidUSGS.jpg|nhỏ|trái|300px|Hình tô pô về Mặt Trăng.]] |

|||

The mg- and alkali-suite rocks are predominantly mafic plutonic rocks. Typical rocks are [[dunite]]s, [[troctolite]]s, [[gabbro]]s, alkali [[anorthosite]]s, and more rarely, [[granite]]. In contrast to the ferroan anorthosite suite, these rocks all have relatively high Mg/Fe ratios in their mafic minerals. In general, these rocks represent intrusions into the already-formed highlands crust (though a few rare samples appear to represent extrusive lavas), and they have been dated to have formed about 4.4–3.9 billion years ago. Many of these rocks have high abundances of, or are genetically related to, the geochemical component [[KREEP]]. |

|||

==Lịch sử, nguồn gốc== |

|||

The lunar maria consist entirely of mare basalts. While similar to terrestrial basalts, they have much higher abundances of iron, are completely lacking in hydrous alteration products, and have a large range of titanium abundances.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/April04/lunarAnorthosites.html | title = The Oldest Moon Rocks | last = Norman | first = M. | publisher = Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology | date = [[2004-04-21]] | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last = Varricchio | first = L. | title = Inconstant Moon | publisher = Xlibris Books | date = 2006 | isbn = 1-59926-393-9}}</ref> |

|||

==Các giả thuyết về tương lai của Mặt Trăng== |

|||

Astronauts have reported that the dust from the surface felt like snow and smelled like spent [[gunpowder]].<ref>[http://science.nasa.gov/headlines/y2006/30jan_smellofmoondust.htm The Smell of Moondust] from [[NASA]]</ref> The dust is mostly made of [[silicon dioxide]] glass (SiO<sub>2</sub>), most likely created from the meteors that have crashed into the Moon's surface. It also contains [[calcium]] and [[magnesium]]. |

|||

==Mặt Trăng trong nghệ thuật== |

|||

Trong tiếng Việt, Mặt Trăng có cách gọi khác: [[wikt:chị Hằng|chị Hằng]], [[wikt:trăng|trăng]], [[wikt:vầng trăng|vầng trăng]], [[wikt:cung Hàn|cung Hàn]]... |

|||

=== Văn học === |

|||

=== Âm nhạc === |

|||

=== Hội họa === |

|||

{{commonscat|Moon in art|Mặt Trăng trong hội họa}} |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

Image:Van der Neer - Moonlit Landscape with Bridge.jpg|[[Ánh trăng]] bên cầu Aert van der Neer. |

|||

Image:P S Krøyer 1899 - Sommeraften ved Skagens strand. Kunstneren og hans hustru.jpg |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==Orbit and relationship to Earth== |

|||

==Xem thêm== |

|||

{{main|Orbit of the Moon}} |

|||

*[[Biển Mặt Trăng]] |

|||

[[Image:NASA-Apollo8-Dec24-Earthrise.jpg|thumb|right|[[Earth]] as viewed from the Moon during the [[Apollo 8]] mission, [[Christmas Eve]], 1968]] |

|||

*[[Pha của Mặt Trăng]] |

|||

The Moon makes a complete orbit around the Earth with respect to the fixed stars (its [[sidereal period]]) about once every 27.3 days. However, since the Earth is moving in its orbit about the Sun at the same time, it takes slightly longer for the Moon to show its same [[lunar phase|phase]] to Earth, which is about 29.5 days (its [[synodic period]]).<ref name="worldbook" /> Unlike most satellites of other planets, the Moon orbits near the [[ecliptic]] and not the Earth's [[equatorial plane]]. It is the largest moon in the solar system relative to the size of its planet. ([[Charon (moon)|Charon]] is larger relative to the [[dwarf planet]] [[Pluto]].) The [[natural satellite]]s orbiting other planets are called "moons", after Earth's Moon. |

|||

*[[Ánh trăng]] |

|||

Most of the tidal effects seen on the Earth are caused by the Moon's gravitational pull, with the Sun making only a small contribution. Tidal effects result in an increase of the mean Earth-Moon distance of about 3.8 m per century, or 3.8 cm per year.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/SEhelp/ApolloLaser.html | title = Apollo Laser Ranging Experiments Yield Results | publisher = NASA | date = [[2005-07-11]] | accessdate = 2007-05-30}}</ref> As a result of the [[conservation of angular momentum]], the increasing semimajor axis of the Moon is accompanied by a gradual slowing of the Earth's rotation by about 0.002 seconds per day per century.<ref>{{cite web | last = Ray | first = R. | date = [[2001-05-15]] | url = http://bowie.gsfc.nasa.gov/ggfc/tides/intro.html | title = Ocean Tides and the Earth's Rotation | publisher = IERS Special Bureau for Tides | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

==Tham khảo== |

|||

(bằng [[tiếng Anh]]) |

|||

* [[Ben Bussey]] and [[Paul Spudlà]], ''The Clementine Atlas of the Moon'', Cambridge University Press, [[2004 in literature|2004]], ISBN 0521815282. |

|||

* [[Patrick Moore]], ''On the Moon'', Sterling Publlishing Co., [[2001 in literature|2001 edition]], ISBN 0304354694. |

|||

* Paul D. Spudis, ''The Once and Future Moon'', Smithsonian Institution Press, [[1996 in literature|1996]], ISBN 1-56098-634-4. |

|||

==Chú thích== |

|||

<references /> |

|||

The Earth–Moon system is sometimes considered to be a [[double planet]] rather than a planet–moon system. This is due to the exceptionally large size of the Moon relative to its host planet; the Moon is a quarter the diameter of Earth and 1/81 its mass. However, this definition is criticised by some, since the common centre of mass of the system (the [[barycentre]]) is located about 1,700 km beneath the surface of the Earth, or about a quarter of the Earth's radius. The surface of the Moon is less than 1/10<sup>th</sup> that of the Earth, and only about a quarter the size of the Earth's land area (or about as large as Russia, Canada, and the U.S. combined). |

|||

==Liên kết ngoài== |

|||

{{commons|Moon}} |

|||

*[http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2004/pdf/1469.pdf Hệ số phản xạ bề mặt Mặt Trăng] đo bởi [[tàu Clementine]] |

|||

*[http://moon.google.com/ Bề mặt Mặt Trăng] tại [[Google]] |

|||

*[http://www.vnexpress.net/Vietnam/Khoa-hoc/2001/11/3B9B6D53/ Giả thiết nguồn gốc Mặt trăng ra đời sau vụ đụng độ giữa hai hành tinh] |

|||

*[http://www.vnexpress.net/Vietnam/Khoa%2Dhoc/2001/08/3B9B3892/ Giả thiết Trái đất tạo ra mặt trăng như thế nào?] |

|||

In 1997, the asteroid [[3753 Cruithne]] was found to have an unusual Earth-associated [[horseshoe orbit]]. However, astronomers do not consider it to be a second moon of Earth, and its orbit is not stable in the long term.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.captaincosmos.clara.co.uk/cruithne.html | last = Vampew | first = A | title = No, it's not our "second" moon!!! | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> Three other [[near-Earth asteroid]]s, (54509) 2000 PH5, (85770) 1998 UP1 and [[2002 AA29]], which exist in orbits similar to Cruithne's, have since been discovered.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Morais | first = M.H.M. | coauthors = Morbidelli, A. | title = The Population of Near-Earth Asteroids in Coorbital Motion with the Earth | journal = Icarus | date = 2002 | volume = 160 | pages = 1–9 | url = http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002Icar..160....1M | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

{{Hệ Mặt Trời}} |

|||

[[Image:Speed of light from Earth to Moon.gif|thumb|600px|center|The relative sizes and separation of the Earth–Moon system are shown to scale above. The beam of light is depicted travelling between the Earth and the Moon in the same time it actually takes light to scale the real distance between them: 1.255 seconds at its mean orbital distance. The light beam helps provide the sense of scale of the Earth-Moon system relative to the Sun, which is 8.28 light-minutes away (photosphere to Earth surface).]] |

|||

[[Thể loại:Mặt Trăng| ]] |

|||

[[Thể loại:Vệ tinh tự nhiên]] |

|||

[[Thể loại:Thuật ngữ thiên văn học]] |

|||

==Ocean tides== |

|||

{{Liên kết chọn lọc|af}} |

|||

Earth’s [[tide|ocean tides]] are initiated by the ''[[tidal force]]'' (a gradient in intensity) of Moon’s gravity and are magnified by a host of effects in Earth’s oceans. The gravitational tidal force arises because the side of Earth facing the Moon (nearest it) is attracted more strongly by the Moon’s gravity than is the center of the Earth and—even less so—the Earth’s far side. The gravitational tide stretches the Earth’s oceans into an ellipse with the Earth in the center. The effect takes the form of two ''bulges''—elevated sea level relative to the Earth; one nearest the Moon and one farthest from it. Since these two bulges rotate around the Earth once a day as it spins on its axis, ocean water is continuously rushing towards the ever-moving bulges. The effects of the two bulges and the massive ocean currents chasing them are magnified by an interplay of other effects; namely frictional coupling of water to Earth’s rotation through the ocean floors, inertia of water’s movement, ocean basins that get shallower near land, and oscillations between different ocean basins. The magnifying effect is a bit like water sloshing high up the sloped end of a bathtub after a relatively small disturbance of one’s body in the deep part of the tub. |

|||

{{Liên kết chọn lọc|ar}} |

|||

{{Liên kết chọn lọc|bg}} |

|||

Gravitational coupling between the Moon and the ocean bulge nearest the Moon affects its orbit. The Earth rotates on its axis in the very same direction, and roughly 27 times faster, than the Moon orbits the Earth. Thus, frictional coupling between the sea floors and ocean waters, as well as water’s [[inertia]], drags the peak of the near-Moon tidal bulge slightly forward of the imaginary line connecting the centers of the Earth and Moon. From the Moon’s perspective, the center of mass of the near-Moon tidal bulge is perpetually slightly ''ahead'' of the point about which it is orbiting. Precisely the opposite effect occurs with the bulge farthest from the Moon; it lags ''behind'' the imaginary line. However it is 12,756 km farther away and has slightly less gravitational coupling to the Moon. Consequently, the Moon is constantly being gravitationally attracted forward in its orbit about the Earth. This gravitational coupling drains [[kinetic energy]] and [[angular momentum]] from the Earth’s rotation (see also, ''[[Day]]'' and ''[[Leap second]]''<span style="margin-left:0.2em">).</span> In turn, angular momentum is added to the [[Orbit of the Moon|Moon’s orbit]], which lifts the Moon into a higher orbit with a longer period. The effect on the Moon’s orbital radius is a small one, just 0.10 [[Parts-per notation|ppb]]/year, but results in a measurable 3.82 cm annual increase in the Earth-Moon distance.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/SEhelp/ApolloLaser.html | title = Apollo Laser Ranging Experiments Yield Results | publisher = NASA | date = [[2005-07-11]] | accessdate = 2007-05-30}}</ref> Cumulatively, this effect becomes ever more significant over time; since when [[Apollo 11|astronauts first landed on the Moon]] approximately {{age|1969|1|19}}<!-- NOTE TO EDITORS: This date, which is 182 days before the landing, rounds the elapsed time to the nearest year. --> years ago, it is now {{days elapsed times factor|1969|7|20|0.00010459|2}} metres<!-- NOTE TO EDITORS: The 0.00010459 factor is based on the 3.82-cm/year value (per Dickey et al.) and averages for the long-term effect of leap years by assuming 365.24 days/year. The resulting precision of the value in metres is less than that of the measured annual rate of change by a factor of two. --> farther away. |

|||

{{Liên kết chọn lọc|cs}} |

|||

{{Liên kết chọn lọc|de}} |

|||

==Eclipses== |

|||

{{Liên kết chọn lọc|en}} |

|||

{{main|Solar eclipse|Lunar eclipse}} |

|||

{{Liên kết chọn lọc|es}} |

|||

[[Image:Solar eclips 1999 4 NR.jpg|thumb|right|The 1999 solar eclipse]] |

|||

{{Liên kết chọn lọc|sk}} |

|||

[[Image:LunarEclipse20070303CRH.JPG|thumb|The 3 March 2007 [[lunar eclipse]]]] |

|||

{{Liên kết chọn lọc|sr}} |

|||

Eclipses can occur only when the Sun, Earth, and Moon are all in a straight line. [[Solar eclipse]]s occur near a [[new moon]], when the Moon is between the Sun and Earth. In contrast, [[lunar eclipse]]s occur near a [[full moon]], when the Earth is between the Sun and Moon. |

|||

Because the Moon's orbit around the Earth is inclined by about 5° with respect to the [[ecliptic|orbit of the Earth around the Sun]], eclipses do not occur at every full and new moon. For an eclipse to occur, the Moon must be near the intersection of the two orbital planes.<ref name="eclipse">{{cite web | last = Thieman | first = J. | coauthors = Keating, S. | date = [[2006-05-02]] | url = http://eclipse99.nasa.gov/pages/faq.html | title = Eclipse 99, Frequently Asked Questions | publisher = NASA | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

The periodicity and recurrence of eclipses of the Sun by the Moon, and of the Moon by the Earth, is described by the [[saros cycle]], which has a period of approximately 6,585.3 days (18 years 11 days 8 hours).<ref>{{cite web |url = http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/SEsaros/SEsaros.html | last = Espenak | first = F |title = Saros Cycle | publisher = NASA | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

The angular diameters of the Moon and the Sun as seen from Earth overlap in their variation, so that both [[total eclipse|total]] and [[annular eclipse|annular]] solar eclipses are possible.<ref>{{cite web | first = F | last = Espenak | date = 2000 | url = http://www.mreclipse.com/Special/SEprimer.html | title = Solar Eclipses for Beginners | publisher = MrEclipse | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> In a total eclipse, the Moon completely covers the disc of the Sun and the solar [[corona]] becomes visible to the [[naked eye]]. Since the distance between the Moon and the Earth is very slightly increasing over time, the angular diameter of the Moon is decreasing. This means that hundreds of millions of years ago the Moon could always completely cover the Sun on solar eclipses so that no annular eclipses were possible. Likewise, about 600 million years from now (assuming that the angular diameter of the Sun will not change), the Moon will no longer cover the Sun completely and only annular eclipses will occur.<ref name="eclipse" /> |

|||

A phenomenon related to eclipse is [[occultation]]. The Moon is continuously blocking our view of the sky by a 1/2 degree-wide circular area. When a bright star or planet ''passes behind'' the Moon it is ''occulted'' or hidden from view. A solar eclipse is an occultation of the Sun. Because the Moon is close to Earth, occultations of individual stars are not visible everywhere, nor at the same time. Because of the precession of the lunar orbit, each year different stars are occulted.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://occsec.wellington.net.nz/total/totoccs.htm | title = Total Lunar Occultations | publisher = Royal Astronomical Society of New Zealand | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

The most recent lunar eclipse was on [[February 20]], [[2008]]. It was a total eclipse. The entire event was visible from South America and most of North America (on Feb. 20), as well as Western Europe, Africa, and western Asia (on Feb. 21). The most recent solar eclipse took place on [[September 11]], [[2007]], visible from southern South America and parts of Antarctica. The next total solar eclipse, on [[August 1]], [[2008]], will have a path of totality beginning in northern Canada and passing through Russia and China.<ref name="Espenak">{{cite web | last = Espenak | first = F. | date = 2007 | url = http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/eclipse.html |title = NASA Eclipse Home Page | publisher = NASA | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

==Observation== |

|||

{{see also|Lunar phase|Earthshine|Observing the Moon}} |

|||

During its brightest phase, at "full moon", the Moon has an [[apparent magnitude]] of about −12.6. By comparison, the Sun has an apparent magnitude of −26.8. When the Moon is in a quarter phase, its brightness is not half of a full moon, but only about a tenth. This is because the lunar surface is not a perfect [[Lambertian reflectance|Lambertian reflector]]. When the Moon is full the [[opposition effect]] makes it appear brighter, but away from full there are shadows projected onto the surface which diminish the amount of reflected light. |

|||

The Moon appears larger when close to the horizon. This is a purely psychological effect (see [[Moon illusion]]). It is actually about 1.5% smaller when the Moon is near the horizon than when it is high in the sky (because it is farther away by up to one Earth radius). |

|||

The moon appears as a relatively bright object in the sky, in spite of its low [[albedo]]. The Moon is about the poorest [[reflector]] in the [[solar system]] and reflects only about 7% of the light incident upon it (about the same proportion as is reflected by a lump of coal).<ref name=Moon>{{cite web | title=How Bright is the Moon? | author=Mike Luciuk | url=http://www.asterism.org/tutorials/tut26-1.htm | accessdate=7/3/08}}</ref> |

|||

[[Color constancy]] in the [[visual system]] recalibrates the relations between the colours of an object and its surroundings, and since the surrounding sky is comparatively dark the sunlit Moon is perceived as a bright object. |

|||

[[Image:Halo around moon.jpg|right|thumb|A [[Halo (optical phenomenon)|halo]] around the Moon]] |

|||

The highest [[altitude (astronomy)|altitude]] of the Moon on a day varies and has nearly the same limits as the Sun. It also depends on the Earth season and lunar phase, with the full moon being highest in winter. Moreover, the 18.6 year nodes cycle also has an influence, as when the ascending node of the lunar orbit is in the vernal equinox, the lunar declination can go as far as 28° each month (which happened most recently in 2006). This results that the Moon can go overhead on latitudes till 28 degrees (e.g. [[Florida]], [[Canary Islands]] or in the southern hemisphere [[Brisbane]]). Slightly more than 9 years later (next time in 2015) the declination reaches only 18° N or S each month. |

|||

The orientation of the Moon's crescent also depends on the latitude of the observation site. Close to the equator, an observer can see a ''boat'' Moon.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://curious.astro.cornell.edu/question.php?number=393 | publisher = Curious About Astronomy | title = Is the Moon seen as a crescent (and not a "boat") all over the world? | date = [[2002-10-18]] | first = K.| last = Spekkens | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

Like the Sun, the Moon can give rise to atmospheric effects, including a 22° [[Halo (optical phenomenon)|halo]] ring, and the smaller [[Corona (meteorology)|coronal rings]] seen more often through thin clouds. For more information on how the Moon appears in Earth's sky, see [[lunar phase]]. |

|||

==Exploration== |

|||

{{main|Exploration of the Moon|Apollo program|Moon landing}} |

|||

{{see also|Robotic exploration of the Moon|Future lunar missions|Colonization of the Moon}} |

|||

The first leap in lunar observation was prompted by the invention of the telescope. [[Galileo Galilei]] made good use of this new instrument and observed mountains and craters on the Moon's surface. |

|||

The [[Cold War]]-inspired [[space race]] between the Soviet Union and the U.S. led to an acceleration of interest in the Moon. Unmanned probes, both flyby and impact/lander missions, were sent almost as soon as launcher capabilities would allow. The Soviet Union's [[Luna programme|Luna program]] was the first to reach the Moon with unmanned [[spacecraft]]. The first man-made object to escape Earth's gravity and pass near the Moon was [[Luna 1]], the first man-made object to impact the lunar surface was [[Luna 2]], and the first photographs of the normally occluded far side of the Moon were made by [[Luna 3]], all in 1959. The first spacecraft to perform a successful lunar soft landing was [[Luna 9]] and the first unmanned vehicle to orbit the Moon was [[Luna 10]], both in 1966.<ref name="worldbook" /> Moon samples have been brought back to Earth by three Luna missions ([[Luna 16]], [[Luna 20|20]], and [[Luna 24|24]]) and the Apollo missions 11 to 17 (except [[Apollo 13]], which aborted its planned lunar landing). |

|||

[[Image:Luna3mosaic.jpg|thumb|left|First images of the [[far side of the Moon]] taken from [[Luna 3]]]] |

|||

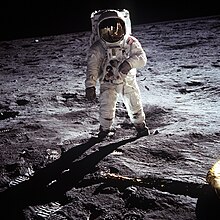

The landing of the first humans on the Moon in 1969 is seen as the culmination of the space race.<ref name=CNN>{{cite news | last = Coren | first = M | title = 'Giant leap' opens world of possibility | publisher = CNN.com | date = [[2004-07-26]] | url = http://edition.cnn.com/2004/TECH/space/07/16/moon.landing/index.html | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

</ref> [[Neil Armstrong]] became the first person to walk on the Moon as the commander of the American mission [[Apollo 11]] by first setting foot on the Moon at 02:56 UTC on [[21 July]], [[1969]]. The American [[Moon landing]] and return was enabled by considerable technological advances, in domains such as [[ablation]] chemistry and [[atmospheric re-entry]] technology, in the early 1960s. |

|||

Scientific instrument packages were installed on the lunar surface during all of the ''Apollo'' missions. Long-lived [[ALSEP]] stations (Apollo lunar surface experiment package) were installed at the [[Apollo 12]], [[Apollo 14|14]], [[Apollo 15|15]], [[Apollo 16|16]], and [[Apollo 17|17]] landing sites, whereas a temporary station referred to as EASEP (Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package) was installed during the Apollo 11 mission. The ALSEP stations contained, among others, heat flow probes, seismometers, magnetometers, and corner-cube retroreflectors. Transmission of data to Earth was terminated on [[30 September]], [[1977]] because of budgetary considerations.<ref>{{cite press release | title = NASA news release 77-47 page 242| date = [[1977-09-01]] | url = http://www.nasa.gov/centers/johnson/pdf/83129main_1977.pdf | accessdate = 2007-08-29 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news | url = http://www.ast.cam.ac.uk/~ipswich/Miscellaneous/Archived_spaceflight_news.htm | accessdate = 2007-08-29 | location = NASA Turns A Deaf Ear To The Moon | date = 1977 | title = OASI Newsletters Archive | last = Appleton | first = James | coauthors = Charles Radley, John Deans, Simon Harvey, Paul Burt, Michael Haxell, Roy Adams, N Spooner and Wayne Brieske }}</ref> Since the [[Lunar laser ranging experiment|lunar laser ranging]] (LLR) corner-cube arrays are passive instruments, they are still being used. Ranging to the LLR stations is routinely performed from earth-based stations with an accuracy of a few centimetres, and data from this experiment are being used to place constraints on the size of the lunar core.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Dickey | first = J. | coauthors = et al. | date = 1994 | title = Lunar laser ranging: a continuing legacy of the Apollo program | journal = Science | volume = 265 |pages = 482–490 | doi = 10.1126/science.265.5171.482 <!--Retrieved from Yahoo! by DOI bot-->}}</ref> |

|||

{{age in years and days|1972|12|14}} have now passed since [[Eugene Cernan]], as part of the mission [[Apollo 17]], left the surface of the Moon on [[14 December]] [[1972]] and no one has set foot on it since. |

|||

[[Image:Aldrin Apollo 11.jpg|thumb|[[Astronaut]] [[Buzz Aldrin]] photographed by [[Neil Armstrong]] during the [[moon landing|first moon landing]] on [[20 July]] [[1969]].]] |

|||

From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, there were 65 instances of artificial objects reaching the Moon (both manned and robotic, with ten in 1971 alone), with the last being [[Luna 24]] in 1976. Only 18 of these were controlled [[moon landings]], with nine completing a round trip from Earth and returning samples of [[moon rocks]]. The Soviet Union then turned its primary attention to [[Venus]] and [[space station]]s, and the U.S. to [[Mars]] and beyond. In 1990, Japan orbited the Moon with the ''[[Hiten]]'' spacecraft, becoming the third country to place a spacecraft into lunar orbit. The spacecraft released a smaller probe, ''Hagormo'', in lunar orbit, but the transmitter failed, thereby preventing further scientific use of the mission. |

|||

In 1994, the U.S. finally returned to the Moon, robotically at least, sending the Joint Defense Department/NASA spacecraft [[Clementine mission|Clementine]]. This mission obtained the first near-global topographic map of the Moon, and the first global [[multispectral]] images of the lunar surface. This was followed by the ''[[Lunar Prospector]]'' mission in 1998. The [[neutron]] [[spectrometer]] on ''Lunar Prospector'' indicated the presence of excess hydrogen at the lunar poles, which is likely to have been caused by the presence of water ice in the upper few metres of the regolith within permanently shadowed craters. The European spacecraft ''[[Smart 1]]'' was launched [[September 27]], [[2003]] and was in lunar orbit from [[November 15]], [[2004]] to [[September 3]], [[2006]]. |

|||

On [[January 14]], [[2004]], U.S. President [[George W. Bush]] called for a plan to return manned missions to the Moon by 2020 (see [[Vision for Space Exploration]]).<ref>{{cite press release|url = http://www.nasa.gov/missions/solarsystem/bush_vision.html| title = President Bush Offers New Vision For NASA | date = [[2004-12-14]] | publisher = NASA | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> NASA is now planning for the construction of a permanent outpost at one of the lunar poles.<ref>{{cite press release | title = |

|||

NASA Unveils Global Exploration Strategy and Lunar Architecture | publisher = NASA | date = [[2006-12-04]] | url = http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2006/dec/HQ_06361_ESMD_Lunar_Architecture.html | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> The People's Republic of China has expressed ambitious plans for exploring the Moon and has started the [[Chang'e program]] for lunar exploration, successfully launching its first spacecraft, [[Chang'e-1]], on [[October 24]], 2007.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://news3.xinhuanet.com/tech/2007-07/07/content_6340313.htm|title =“嫦娥一号”发射时间确定 但未到公布时机|publisher= [[XINHUA Online]]|date=July 7, 2007|accessdate=July 12|accessyear=2007}}</ref> [[India]] intends to launch several unmanned missions, beginning with ''[[Chandrayaan|Chandrayaan I]]'' in February 2008, followed by ''Chandrayaan II'' in 2010 or 2011; the latter is slated to include a robotic lunar rover. India also has expressed its hope for a manned mission to the Moon by 2030.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.hindu.com/thehindu/holnus/008200609212240.htm| publisher = The Hindu | title = Kalam visualises establishing space industry| date = [[2006-09-21]] | accessdate = 2007-08-28}}</ref> The U.S. will launch the ''[[Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter]]'' in 2008. Russia also announced to resume its previously frozen project ''[[Luna-Glob]]'', consisting of an unmanned lander and orbiter, which is slated to land in 2012.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.aviationnow.com/avnow/news/channel_awst_story.jsp?id=news/aw060506p2.xml | title = Russia Plans Ambitious Robotic Lunar Mission | last = Covault | first = C. | publisher = Aviation Week | date = [[2006-06-04]] | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Google Lunar X Prize]], announced [[13 September]] [[2007]], hopes to boost and encourage privately funded lunar exploration. The [[X Prize Foundation]] is offering anyone 20 million dollars US who can land a robotic rover on the Moon and meet other specified criteria. |

|||

On [[September 14]], [[2007]] the [[Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency]] launched [[SELENE]] a lunar orbiter which is fitted with a [[High-definition video|high-definition camera]] and two small satellites. The mission is expected to last one year.<ref>[http://en.epochtimes.com/news/7-10-1/60291.html Japan Embarks on the Largest Moon Mission Since Apollo]</ref> |

|||

==Human understanding== |

|||

{{see also|The Moon in mythology|Moon in art and literature|Lunar effect|Artemis}} |

|||

[[Image:Hevelius Map of the Moon 1647.jpg|thumb|Map of the Moon by [[Johannes Hevelius]] (1647)]] |

|||

The Moon has been the subject of many works of art and literature and the inspiration for countless others. It is a motif in the visual arts, the performing arts, poetry, prose and music. A 5,000-year-old rock carving at [[Knowth]], [[Ireland]] may represent the Moon, which would be the earliest depiction discovered.<ref name=spacetoday>{{cite web | url = http://www.spacetoday.org/SolSys/Earth/OldStarCharts.html | title = Carved and Drawn Prehistoric Maps of the Cosmos | publisher = Space Today Online | date = 2006 | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> In many prehistoric and ancient cultures, the Moon was thought to be a [[lunar deity|deity]] or other [[supernatural]] phenomenon, and [[Moon (astrology)|astrological views]] of the Moon continue to be propagated today. |

|||

Among the first in the Western world to offer a scientific explanation for the Moon was the [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] philosopher [[Anaxagoras]] (d. 428 BC), who reasoned that the Sun and Moon were both giant spherical rocks, and that the latter reflected the light of the former. His atheistic view of the heavens was one cause for his imprisonment and eventual exile.<ref>{{cite web | last = O'Connor | first = J.J. | coauthors = Robertson, E.F. | date = February 1999 | url = http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Anaxagoras.html | title = Anaxagoras of Clazomenae | publisher = University of St Andrews | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

In [[Aristotle]]'s (384–322 BC) description of the universe, the Moon marked the boundary between the spheres of the mutable elements (earth, water, air and fire), and the imperishable stars of [[aether]]. This separation was held to be part of physics for many centuries after.<ref>{{cite book | last = [[C. S. Lewis|Lewis, C.S.]] | title = The Discarded Image | pages = 108 | publisher = Cambridge University Press | date = 1964 | location = Cambridge | isbn = 0-521047735-2}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Moon and red blue haze.jpg|left|thumb|Moon against the [[Belt of Venus]]]] |

|||

During the [[Warring States]] of [[China]], astronomer [[Shi Shen]] (fl. 4th century BC) gave instructions for predicting solar eclipse and lunar eclipse based on the relative positions of the moon and sun.<ref>Needham, Joseph. (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and Earth''. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Page 411.</ref> Although the Chinese of the [[Han Dynasty]] (202 BC–202 AD) believed the moon to be energy equated to ''[[qi]]'', their 'radiating influence' theory recognized that the light of the moon was merely a reflection of the sun (mentioned by Anaxagoras above).<ref name="needham volume 3 413 414">Needham, Joseph. (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and Earth''. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Page 413–414.</ref> This was supported by mainstream thinkers such as [[Jing Fang]] (78–37 BC) and [[Zhang Heng]] (78–139 AD), but it was also opposed by the influential philosopher [[Wang Chong]] (27–97 AD).<ref name="needham volume 3 413 414"/> Jing Fang noted the sphericity of the moon, while Zhang Heng accurately described lunar eclipse and solar eclipse.<ref name="needham volume 3 413 414"/><ref>Needham, Joseph. (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and Earth''. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Page 227.</ref> These assertions were supported by [[Shen Kuo]] (1031–1095) of the [[Song Dynasty]] (960–1279) who created an allegory equating the waxing and waning of the moon to a round ball of reflective silver that, when doused with white powder and viewed from the side, would appear to be a crescent.<ref name="needham volume 3 415 416">Needham, Joseph. (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and Earth''. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Page 415–416.</ref> He also noted that the reason for the sun and moon not eclipsing every time their paths met was because of a small obliquity in their orbital paths.<ref name="needham volume 3 415 416"/> |

|||

By the [[Middle Ages]], before the invention of the telescope, more and more people began to recognise the Moon as a sphere, though they believed that it was "perfectly smooth".<ref>{{cite web | last = Van Helden | first = A. | date = 1995 | url = http://galileo.rice.edu/sci/observations/moon.html | title = The Moon | publisher = Galileo Project | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> In 1609, [[Galileo Galilei]] drew one of the first telescopic drawings of the Moon in his book {{lang|la|''[[Sidereus Nuncius]]''}} and noted that it was not smooth but had mountains and craters. Later in the 17th century, [[Giovanni Battista Riccioli]] and [[Francesco Maria Grimaldi]] drew a map of the Moon and gave many craters the names they still have today. |

|||

[[Image:Le Voyage dans la lune.jpg|thumb|Still from silent film ''{{lang|fr|[[Le Voyage dans la Lune]]}}'' (1902) by [[Georges Méliès]]]] |

|||

On maps, the dark parts of the Moon's surface were called ''maria'' (singular ''mare'') or seas, and the light parts were called ''terrae'' or continents. |

|||

The possibility that the Moon contains vegetation and is inhabited by selenites was seriously considered by major astronomers even into the first decades of the 19th century. The contrast between the brighter highlands and darker maria create the patterns seen by different cultures as the [[Man in the Moon]], the rabbit and the buffalo, among others. |

|||

In 1835, the [[Great Moon Hoax]] fooled some people into thinking that there were exotic animals living on the Moon.<ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.museumofhoaxes.com/moonhoax.html | title = The Great Moon Hoax | last = Boese | first = A. | publisher = Museum of Hoaxes | date = 2002 | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> Almost at the same time however (during 1834–1836), [[Wilhelm Beer]] and [[Johann Heinrich Mädler]] were publishing their four-volume {{lang|la|''Mappa Selenographica''}} and the book {{lang|de|''Der Mond''}} in 1837, which firmly established the conclusion that the Moon has no bodies of water nor any appreciable atmosphere. |

|||

The far side of the Moon remained completely unknown until the [[Luna 3]] probe was launched in 1959, and was extensively mapped by the [[Lunar Orbiter program]] in the 1960s. |

|||

==Legal status== |

|||

{{main|Space law}} |

|||

Although several pennants of the [[Soviet Union]] were scattered by [[Luna 2]] in 1959 and by later landing missions, and [[U.S. flag]]s have been symbolically planted on the Moon, no nation currently claims ownership of any part of the Moon's surface. Russia and the U.S. are party to the [[Outer Space Treaty]], which places the Moon under the same jurisdiction as [[international waters]] ({{lang|la|''[[res communis]]''}}). This treaty also restricts the use of the Moon to peaceful purposes, explicitly banning military installations and [[weapons of mass destruction]] (including [[nuclear weapons]]).<ref>{{cite web | title = International Space Law | publisher = United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs | url = http://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/SpaceLaw/index.html | date = 2006 | accessdate = 2007-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

A second treaty, the [[Moon Treaty]], was proposed to restrict the exploitation of the Moon's resources by any single nation, but it has not been signed by any of the [[space-faring nations]]. Several individuals have made [[Extraterrestrial real estate|claims]] to the Moon in whole or in part, although none of these is generally considered credible.<ref>[http://www.theregister.co.uk/2006/12/08/nasa_real_estate/ theregister.co.uk] "NASA crushes lunar real estate industry"</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{portal|Solar System|Solar system.jpg}} |

|||

<div style="-moz-column-count:3; column-count:3;"> |

|||

* [[3753 Cruithne]] |

|||

* [[Blue moon]] |

|||

* [[Extraterrestrial real estate]] |

|||

* [[Google Lunar X Prize]] |

|||

* [[Late Heavy Bombardment]] |

|||

* [[List of artificial objects on the Moon]] |

|||

* [[List of craters on the Moon]] |

|||

* [[List of features on the Moon]] |

|||

* [[List of maria on the Moon]] |

|||

* [[List of mountains on the Moon]] |

|||

* [[List of valleys on the Moon]] |

|||

* [[List of Apollo astronauts]] (includes list of people who have landed on the Moon) |

|||

* [[Lunar space elevator]] |

|||

* [[Month]] |

|||

* [[Moon in art and literature]] |

|||

* [[Selenography]] |

|||

* [[Space weathering]] |

|||

</div> |

|||

==References== |

|||

;Cited |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

;General |

|||

<div class="references-small"> |

|||

* {{cite book| title=The Clementine Atlas of the Moon | last = Bussey | first = B. | coauthors = [[Paul Spudis|Spudis, P.D.]] | publisher = Cambridge University Press | date = 2004 | isbn = 0-521-81528-2}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | last = Jolliff | first = B. | coauthors = Wieczorek, M.; Shearer, C.; Neal, C. (eds.) | title = New views of the Moon | journal = Rev. Mineral. Geochem. |publisher = Min. Soc. Amer. | location = Chantilly, Virginia | pages = 721 | date = 2006 | volume = 60 | url = http://www.minsocam.org/msa/RIM/Rim60.html | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite book| title = The Big Splat, or How Our Moon Came to Be | last = Mackenzie | first = Dana | publisher = John Wiley & Sons, Inc | location = Hoboken, New Jersey | date = 2003 }} |

|||

* {{cite book| title = On the Moon | last = [[Patrick Moore|Moore, P.]] | publisher = Sterling Publishing Co. | location = Tucson, Arizona | date = 2001 | isbn = 0-304-35469-4}} |

|||

* {{cite book| title = The Once and Future Moon | last = Spudis | first = P.D. | publisher = Smithsonian Institution Press | date = 1996 | isbn = 1-56098-634-4}} |

|||

* {{cite book | last = Taylor | first = S.R. | title = Solar system evolution | publisher = Cambridge Univ. Press | pages = 307 | date = 1992}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | last = Wilhelms | first = D.E. | title = Geologic History of the Moon | journal = U.S. Geological Survey Professional paper | date = 1987 | volume = 1348 | url = http://ser.sese.asu.edu/GHM/ | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite book| title = To a Rocky Moon: A Geologist's History of Lunar Exploration | last = Wilhelms | first = D.E. | publisher = University of Arizona Press | location = Tucson, Arizona | date = 1993}} |

|||

</div> |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{sisterlinks|Moon}} |

|||

;Images and maps |

|||

* {{cite web | last = Constantine | first = M. | title = Apollo Panoramas | publisher = moonpans.com | date = 2004 | url = http://moonpans.com/missions.htm | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Clementine Lunar Image Browser 1.5 | publisher = U.S. Navy | date = [[2003-10-15]] | url = http://www.cmf.nrl.navy.mil/clementine/clib/ | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Digital Lunar Orbiter Photographic Atlas of the Moon | publisher = Lunar and Planetary Institute | url = http://www.lpi.usra.edu/resources/lunar_orbiter/ | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Google Moon | publisher = Google | date = 2007 | url = http://moon.google.com | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Lunar Atlases | publisher = Lunar and Planetary Institute | url = http://www.lpi.usra.edu/resources/lunar_atlases/ | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | last = Aeschliman | first = R. | title = Lunar Maps | work = Planetary Cartography and Graphics | url = http://ralphaeschliman.com/id26.htm | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Lunar Photo of the Day | date = 2007 | url = http://www.lpod.org/ | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Moon | work = World Wind Central | publisher = NASA | date = 2007 | url = http://www.worldwindcentral.com/wiki/Moon | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = The Moon: 50 fantastic features | publisher = Skymania | date = 2007 | url = http://moon.skymania.com/ | accessdate = 2007-09-29}} |

|||

* [http://wms.selene.jaxa.jp/data/en/hdtv/007/earth-rise.html Video of Earth rising from moon orbit] by the camera of the JAXA (Japanese) satellite [[Kaguya]]. (The [[Earth]] only appearse to rise because of the orbiting satellite. Seen from the moon surface, the earth doesn't move since the moon always shows the same side to the earth.) |

|||

;Exploration |

|||

* {{cite web | last = Jones | first = E.M. | title = Apollo Lunar Surface Journal | publisher = NASA | date = 2006 | url = http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/alsj/ | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Exploring the Moon | publisher = Lunar and Planetary Institute | url = http://www.lpi.usra.edu/expmoon/ | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | last = Teague | first = K. | title = The Project Apollo Archive | date = 2006 | url = http://www.apolloarchive.com/apollo_archive.html | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

;Moon phases |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Current Moon Phase | date = 2007 | url = http://www.moonphaseinfo.com/ | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = NASA's SKYCAL - Sky Events Calendar | publisher = NASA Eclipse Home Page | url = http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/SKYCAL/SKYCAL.html | accessdate = 2007-08-27}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Virtual Reality Moon Phase Pictures | publisher = U.S. Naval Observatory | url = http://tycho.usno.navy.mil/vphase.html | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Find moonrise, moonset and moonphase for a location | date = 2008 | url = |

|||

http://www.timeanddate.com/worldclock/moonrise.html | accessdate = 2008-02-18}} |

|||

;Others |

|||

* {{cite web | title = All About the Moon | publisher = Space.com | date = 2007 | url = http://www.space.com/moon/ | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* [http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/profile.cfm?Object=Moon Earth's Moon Profile] by [http://solarsystem.nasa.gov NASA's Solar System Exploration] |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Archive of Moon Articles | publisher = Planetary Science Research Discoveries | date = 2007 | url = http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/Archive/Archive-Moon.html | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | last = Williams | first = D.R. | title = Moon Fact Sheet | publisher = NASA | date = 2006 | url = http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/moonfact.html | accessdate = 2007-04-12}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title = Moon Wiki | date = 2007 | url = http://the-moon.wikispaces.com/ | accessdate = 2007-09-06}} |

|||

* {{cite web | last = Cain | first = Fraser | title= Where does the Moon Come From? | publisher = Universe Today | url= http://www.astronomycast.com/astronomy/episode-17-where-does-the-moon-come-from/ | accessdate = 2008-04-01}} |

|||

* [http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/Archive/Archive-Moon.html Moon articles from Planetary Science Research Discoveries] |

|||

;Cartographic resources |

|||

* [http://planetologia.elte.hu/1cikkeke.phtml?cim=holdmapinte.html Map of the Moon] |

|||

* [http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/jsp/FeatureTypes2.jsp?system=Earth&body=Moon&systemID=3&bodyID=11 Lunar nomenclature] |

|||

* [http://pdsmaps.wr.usgs.gov/PDS/public/explorer/html/moonpick.htm PDS Map-a-Planet] |

|||

{{The Moon}} |

|||

{{Solar System moons (compact)}} |

|||

{{Solar System}} |

|||

<!--Categories--> |

|||

[[Category:Moon| ]] |

|||

[[Category:Moons]] |

|||

<!--Other languages--> |

|||

{{Link FA|af}} |

|||

{{Link FA|bg}} |

|||

{{Link FA|de}} |

|||

{{Link FA|es}} |

|||

{{Link FA|hu}} |

|||

{{Link FA|mr}} |

|||

{{Link FA|sk}} |

|||

{{Link FA|tr}} |

|||

[[af:Maan]] |

[[af:Maan]] |

||

| Dòng 388: | Dòng 545: | ||

[[ay:Phaxsi]] |

[[ay:Phaxsi]] |

||

[[az:Ay]] |

[[az:Ay]] |

||

[[id:Bulan]] |

|||

[[ms:Bulan (satelit)]] |

|||

[[bn:চাঁদ]] |

[[bn:চাঁদ]] |

||

[[zh-min-nan:Go̍eh-niû]] |

[[zh-min-nan:Go̍eh-niû]] |

||

[[jv:Bulan]] |

|||

[[be:Месяц, спадарожнік Зямлі]] |

[[be:Месяц, спадарожнік Зямлі]] |

||

[[bs:Mjesec (mjesec)]] |

[[bs:Mjesec (mjesec)]] |

||

| Dòng 408: | Dòng 562: | ||

[[et:Kuu]] |

[[et:Kuu]] |

||

[[el:Σελήνη]] |

[[el:Σελήνη]] |

||

[[en:Moon]] |

|||

[[es:Luna]] |

[[es:Luna]] |

||

[[eo:Luno]] |

[[eo:Luno]] |

||

| Dòng 428: | Dòng 581: | ||

[[io:Luno]] |

[[io:Luno]] |

||

[[ilo:Bulan]] |

[[ilo:Bulan]] |

||

[[id:Bulan]] |

|||

[[ia:Luna]] |

[[ia:Luna]] |

||

[[iu:ᑕᖅᑭᖅ/taqqiq]] |

[[iu:ᑕᖅᑭᖅ/taqqiq]] |

||

| Dòng 433: | Dòng 587: | ||

[[it:Luna]] |

[[it:Luna]] |

||

[[he:הירח]] |

[[he:הירח]] |

||

[[jv:Bulan]] |

|||

[[pam:Bulan]] |

[[pam:Bulan]] |

||

[[kn:ಚಂದ್ರ]] |

[[kn:ಚಂದ್ರ]] |

||

| Dòng 452: | Dòng 607: | ||

[[mt:Qamar]] |

[[mt:Qamar]] |

||

[[mr:चंद्र]] |

[[mr:चंद्र]] |

||

[[ms:Bulan (satelit)]] |

|||

[[mn:Сар]] |

[[mn:Сар]] |

||

[[nah:Mētztli]] |

[[nah:Mētztli]] |

||

Phiên bản lúc 00:34, ngày 19 tháng 5 năm 2008

| Đặc điểm quỹ đạo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bán trục lớn | 384.400 km (0,0026 AU) | ||||||

| Chu vi quỹ đạo | 2.413.402 km (0,016 AU) | ||||||

| Độ lệch tâm | 0,0554 | ||||||

| Cận điểm | 363.104 km (0,0024 AU) | ||||||

| Viễn điểm | 405.696 km (0,0027 AU) | ||||||

| Chu kỳ | 27,321 66155 ngày (27 ngày 7 giờ 43,2 phút) | ||||||

| Chu kỳ biểu kiến | 29.530 588 ngày (29 ngày 12 giờ 44,0 phút) | ||||||

| Tốc độ quỹ đạo trung bình |

1,022 km/s | ||||||

| Tốc độ quỹ đạo cực đại |

1,082 km/s | ||||||

| Tốc độ quỹ đạo cực tiểu |

0,968 km/s | ||||||

| Độ nghiêng | thay đổi giữa 28,60° và 18,30° (5,145 396° so với mặt phẳng hoàng đạo) xem quỹ đạo | ||||||

| Kinh độ điểm mọc | 125,08° | ||||||

| Góc cận điểm | 318,15° | ||||||

| Là vệ tinh của | Trái Đất | ||||||

| Đặc điểm vật lý | |||||||

| Đường kính tại xích đạo |

3.476,2 km (0,273 Trái Đất) | ||||||

| Đường kính tại cực | 3.472,0 km (0,273 Trái Đất) | ||||||

| Độ dẹp | 0,0012 | ||||||

| Diện tích bề mặt | 3,793×107 km2 (0,074 Trái Đất) | ||||||

| Thể tích | 2,197×1010 km3 (0,020 Trái Đất) | ||||||

| Khối lượng | 7,347 673×1022 kg (0.0123 Trái Đất) | ||||||

| Tỉ trọng trung bình | 3,344 g/cm3 | ||||||

| Gia tốc trọng trường tại xích đạo |

1,622 m/s2, (0,1654 g) | ||||||

| Tốc độ thoát | 2,38 km/s | ||||||

| Chu kỳ tự quay | 27,321 661 ngày | ||||||

| Vận tốc tự quay | 16,655 km/h (tại xích đạo) | ||||||

| Độ nghiêng trục quay | thay đổi giữa 3,60° và 6,69° (1,5424° so với mặt phẳng hoàng đạo) xem quỹ đạo | ||||||

| Xích kinh độ của cực bắc |

266,8577° (17 h 47 m 26 s) | ||||||

| Thiên độ | 65,6411° | ||||||

| Độ phản xạ | 0,12 | ||||||

| Độ sáng biểu kiến | -12,74 | ||||||

| Nhiệt độ bề mặt |

| ||||||

| Thành phần thạch quyển | |||||||

| Ôxy | 43% | ||||||

| Silíc | 21% | ||||||

| Nhôm | 10% | ||||||

| Canxi | 9% | ||||||

| Sắt | 9% | ||||||

| Magiê | 5% | ||||||

| Titan | 2% | ||||||

| Niken | 0,6% | ||||||

| Natri | 0,3% | ||||||

| Crôm | 0,2% | ||||||

| Kali | 0,1% | ||||||

| Mangan | 0.1% | ||||||

| Lưu huỳnh | 0,1% | ||||||

| Phốtpho | 500 ppm | ||||||

| Cácbon | 100 ppm | ||||||

| Nitơ | 100 ppm | ||||||

| Hiđrô | 50 ppm | ||||||

| Hêli | 20 ppm | ||||||

| Đặc điểm khí quyển | |||||||

| Áp suất khí quyển | 3 × 10-13kPa | ||||||

| Hêli | 25% | ||||||

| Neon | 25% | ||||||

| Hiđrô | 23% | ||||||

| Argon | 20% | ||||||

| Mêtan |

rất ít | ||||||

Mặt trăng (Tiếng Latinh: Luna, ký hiệu bởi hình Unicode: ☾) là vệ tinh tự nhiên duy nhất của Trái đất và là vệ tinh tự nhiên lớn thứ năm trong Hệ mặt trời.

Khoảng cách từ tâm tới tâm giữa Trái đất và Mặt trăng là 384,403 km, khoảng ba mươi lần đường kính Trái đất. Đường kính Mặt trăng là 3,474 km,[1] hơi nhỏ hơn một phần tư đường kính Trái đất. Điều này có nghĩa khối lượng Mặt trăng khoảng bằng 2 phần trăm khối lượng Trái đất và lực hút hấp dẫn tại bề mặt Mặt trăng bằng 17 phần trăm lực hấp dẫn trên bề mặt Trái đất. Mặt trăng thực hiện hết một vòng quỹ đạo quanh Mặt đất trong 27.3 ngày (giai đoạn quỹ đạo), và các biến đổi định kỳ trong hình học hệ Trái đất-Mặt trăng–Mặt trời là nguyên nhân gây ra các pha mặt trăng lặp lại sau mỗi 29.5 ngày (giai đoạn giao hội).

Mặt trăng là vật thể vũ trụ duy nhất đã từng được con người đặt chân tới. Vật thể nhân tạo đầu tiên thoát khỏi lực hấp dẫn Trái đất tới gần Mặt trăng là Luna 1 của Liên bang Xô viết, vật thể nhân tạo đầu tiên lao xuống bề mặt Mặt trăng là Luna 2, và những bức ảnh đầu tiên về phần bề mặt phía sau của Mặt trăng đã được Luna 3 chụp, tất cả đều diễn ra năm 1959. Tàu vũ trụ đầu tiên thực hiện hạ cánh mềm thành công là Luna 9, và tàu vũ trụ không người lái đầu tiên bay quanh Mặt trăng là Luna 10, cả hai đều diễn ra năm 1966.[1] Chương trình Apollo của Hoa Kỳ đã thực hiện được những cuộc đổ bộ duy nhất của con người xuống Mặt trăng cho tới thời điểm này, tổng cộng gồm sáu lần hạ cánh trong giai đoạn từ 1969 tới 1972. Việc thám hiểm Mặt trăng của loài người đã dừng lại với sự chấm dứt của chương trình Apollo, dù nhiều quốc gia đã thông báo các kế hoạch gửi người hay tàu vũ trụ robot tới Mặt trăng.

Tên gọi và từ nguyên

Không giống như vệ tinh của những hành tinh khác, Mặt trăng -vệ tinh của Trái đất- không có tên riêng nào khác trong tiếng Anh ngoài cái tên "the Moon" (viết hoa[2]).

Từ moon (Mặt trăng trong tiếng Anh) là một từ thuộc ngôn ngữ Germanic, liên quan tới từ mensis trong tiếng Latinh; từ này lại xuất phát từ gốc Proto-Indo-European me-, cũng xuất hiện trong measure (đo lường)[3] (thời gian), với sự gợi nhớ tới tầm quan trọng của nó trong việc đo đạc thời gian trong những từ có nguồn gốc từ nó như Monday (thứ hai trong tiếng Anh), month (tháng trong tiếng Anh) và menstrual (hàng tháng). Trong tiếng Anh, từ moon chỉ có nghĩa "Mặt trăng" cho tới tận năm 1665, khi nó được mở rộng nghĩa để chỉ những vệ tinh tự nhiên mới được khám phá của các hành tinh khác.[3] Mặt trăng thỉnh thoảng cũng được gọi theo tên tiếng Latinh của nó, Luna, để phân biệt với các vệ tinh tự nhiên khác, tính từ có liên quan là lunar, và một tiền tố tính từ seleno- hay hậu tố -selene (theo vị thần Hy Lạp Selene).

Bề mặt Mặt trăng

Hai phía Mặt trăng

Mặt trăng nằm trên quỹ đạo quay đồng bộ, có nghĩa là nó hầu như giữ nguyên một mặt hướng về Trái đất ở tất cả mọi thời gian. Buổi đầu mới hình thành, Mặt trăng quay chậm dần và bị khoá ở vị trí hiện tại vì những hiệu ứng ma sát xuất hiện cùng hiện tượng biến dạng thuỷ triều do Trái đất gây ra.[4]

Từ đã rất lâu khi Mặt trăng còn quay nhanh hơn hiện tại rất nhiều, bướu thuỷ triều của nó chạy trước đường nối Trái đất-Mặt trăng bởi nó không thể làm xẹp bướu đủ nhanh để giữ bướu này luôn ở trên đường thẳng đó.[5] Lực quay khiến bướu luôn vượt quá đường nối này. Hiện tượng này gây ra mô men xoắn, làm giảm tốc độ quay của Mặt trăng, như một lực vặn siết chặt đai ốc. Khi tốc độ quay của Mặt trăng giảm xuống đủ để cân bằng với tốc độ quỹ đạo của nó, khi ấy bướu luôn hướng về phía Trái đất, bướu nằm trên đường thẳng nối Trái đất-Mặt trăng, và lực xoắn biến mất. Điều này giải thích tại sao Mặt trăng quay với tốc độ bằng tốc độ quỹ đạo và chúng ta luôn chỉ nhìn thấy một phía của Mặt trăng.

Các biến đổi nhỏ (đu đưa) trong góc quan sát cho phép chúng ta nhìn thấy được khoảng 59% bề mặt Mặt trăng (nhưng luôn chỉ là một nửa ở một thời điểm).[1]

|

| |

| Phần bề mặt nhìn thấy được của Mặt trăng | Phần bề mặt không nhìn thấy được của Mặt trăng |

Mặt quay về phía Trái đất được gọi là phần nhìn thấy, và phía đối diện được gọi là phần không nhìn thấy. Phần không nhìn thấy thỉnh thoảng còn được gọi là "phần tối," nhưng trên thực tế nó cũng được chiếu sáng thường xuyên như phần nhìn thấy: một lần trong mỗi ngày Mặt trăng, trong tuần trăng mới chúng ta quan sát nó từ Trái đất khi phần không nhìn thấy đang tối. Phần không nhìn thấy của Mặt trăng lần đầu tiên được tàu thăm dò Xô viết Luna 3 chụp ảnh năm 1959. Một đặc điểm phân biệt của phần không nhìn thấy được là nó hầu như không có các vùng tối Mặt trăng.

Các vùng tối trên Mặt trăng

Các đồng bằng tối và hầu như không có đặc điểm riêng trên Mặt trăng có thể được nhìn thấy rõ bằng mặt thường được gọi là các vùng tối, từ tiếng Latinh có nghĩa là biển, bởi chúng được các nhà thiên văn học cổ đại cho là những nơi chứa đầy nước. Hiện chúng đã được biết chỉ là những bề dung nham basalt cổ lớn đã đông đặc. Đa số các dung nham này đã được phun ra hay chảy vào những chỗ lõm hình thành nên sau các vụ va chạm thiên thạch hay sao chổi vào bề mặt Mặt trăng. (Oceanus Procellarum là trường hợp khác bởi nó không được hình thành do va chạm). Các biển xuất hiện dày đặc phía bề mặt nhìn thấy được của Mặt trăng, phía không nhìn thấy có rất ít biển và chúng chỉ chiếm khoảng 2% bề mặt,[6] so với khoảng 31% ở phía đối diện.[1] Cách giải thích có vẻ đúng đắn nhất cho sự khác biệt này liên quan tới sự tập trung cao của các yếu tố sinh nhiệt phía bề mặt nhìn thấy được, như đã được thể hiện bởi các bản đồ địa hóa học có được từ những máy quang phổ tia gamma.[7][8] Nhiều vùng có chứa những núi lửa hình vòng cung (shield vocano) và núi xuất hiện bên trong các biển ở phía có thể nhìn thấy.[9]

Terrae

Các vùng có màu sáng trên Mặt trăng được gọi là terrae, hay theo cách thông thường hơn là các cao nguyên, bởi chúng cao hơn hầu hết các biển. Nhiều rặng núi cao ở phía bề mặt nhìn thấy được chạy dọc theo bờ ngoài các vùng trũng do va chạm lớn, nhiều vùng trũng này đã được basalt lấp kín. Chúng được cho là các tàn tích còn lại của các vòng tròn bên ngoài của vùng trũng do va chạm.[10] Không giống Trái đất, không một ngọn núi lớn nào trên Mặt trăng được cho là được hình thành từ các sự kiện kiến tạo.[11]

Các bức ảnh được chụp bởi Clementine mission năm 1994 cho thấy bốn vùng núi thuộc vòng tròn núi lửa Peary rộng 73 km tại cực bắc Mặt trăng luôn được chiếu sáng trong cả ngày mặt trăng. Những đỉnh sáng vĩnh cửu này có thể bởi độ nghiêng trục rất nhỏ trên mặt phẳng hoàng đạo của Mặt trăng. Không vùng sáng vĩnh cửu nào được phát hiện ở phía cực nam, dù vòng tròn của núi lửa Shackleton được chiếu sáng khoảng 80% trong ngày mặt trăng. Một hậu quả khác từ việc Mặt trăng có độ nghiêng trục nhỏ là một số vùng đáy của các núi lửa cực luôn ở trong bóng tối.[12]

Miệng núi lửa do va chạm

Bề mặt Mặt trăng cho thấy bằng chứng rõ ràng rằng nó đã bị ảnh hưởng nhiều bởi các sự kiện va chạm thiên thạch.[13] Các núi lửa do va chạm hình thành khi các thiên tạch và sao chổi va chạm vào bề mặt Mặt trăng, và nói chung có khoảng nửa triệu núi lửa với đường kính hơn 1 km. Bởi các núi lửa do va chạm hình thành với tỷ lệ bất biến, số lượng miệng núi lửa trên một đơn vị diện tích có thể được sử dụng để ước tính tuổi của bề mặt (xem Đếm miệng núi lửa). Vì không có khí quyển, thời tiết và các hoạt động địa lý gần đây nên nhiều miệng núi lửa được bảo tồn trong trạng thái khá tốt so với những miệng núi lửa va chạm trên bề mặt Trái đất.

Miệng núi lửa lớn nhất trên Mặt trăng, cũng là miệng núi lửa lớn nhất đã được biết trong Hệ mặt trời, là Vùng trũng Nam cực-Aitken. Vùng này nằm ở phía bề mặt không nhìn thấy, giữa Nam Cực và Xích đạo, và có đường kính khoảng 2,240 km và sâu 13 km.[14] Các vùng trũng va chạm lớn ở phía bề mặt nhìn thấy được gồm Imbrium, Serenitatis, Crisium, và Nectaris.

Regolith

Bao trùm phía ngoài bề mặt Mặt trăng là một lớp bụi rất mịn (vật chất vỡ thành các phần tử rất nhỏ) và lớp bề mặt vỡ vụn do va chạm này được gọi là regolith. Bởi regolith được hình thành từ các quá trình va chạm, regolith của các bề mặt già hơn thường dày hơn tại các nơi bề mặt trẻ khác. Đặc biệt, người ta đã ước tính rằng regolith có độ dày thay đổi từ khoảng 3–5 m tại các biển, và khoảng 10–20 m trên các cao nguyên.[15] Bên dưới lớp regolith mịn là cái thường được gọi là megaregolith. Lớp này dày hơn rất nhiều (khoảng hàng chục km) và gồm lớp nền đá đứt gãy.[16]

Nước trên Mặt trăng

Những vụ bắn phá liên tiếp của các sao chổi và các thiên thạch có lẽ đã mang tới một lượng nước nhỏ vào bề mặt Mặt trăng. Nếu như vậy, ánh sáng mặt trời sẽ phân chia đa phần lượng nước này thành các nguyên tố cấu tạo là hydro và oxy, cả hai chất này theo thời gian nói chung lại bay vào vũ trụ, vì lực hấp dẫn của Mặt trăng yếu. Tuy nhiên, vì trục nghiêng của Mặt trăng so với trục quay trên mặt phẳng hoàng đạo chỉ chênh 1.5°, có một số miệng núi lửa sâu ở các cực không bao giờ bị ánh sáng Mặt trời trực tiếp chiếu tới (xem Núi lửa Shackleton). Các phân tử nước ở trong các núi lửa này có thể ổn định trong một thời gian dài.

Clementine đã vẽ bản đồ các miệng núi lửa tại cực nam Mặt trăng[17] nơi luôn ở trong bóng tối, và các cuộc thử nghiệm mô phỏng máy tính cho thấy có thể có tới 14,000 km² luôn ở trong bóng tối.[12] Các kết quả thám sát radar từ phi vụ Clementine cho rằng có một số túi nước nhỏ, đóng băng nằm gần bề mặt, và dữ liệu từ máy quang phổ neutron của Lunar Prospector cho thấy sự tập trung lớn dị thường của hydro ở vài mét phía trên của regolith gần các vùng cực.[18] Các ước tính tổng số lượng băng gần một kilômét khổi.

Băng có thể được khai thác và phân chia thành nguyên tử cấu tạo ra nó là hydro và oxy bằng các lò phản ứng hạt nhân hay các trạm điện mặt trời. Sự hiện diện của lượng nước sử dụng được trên Mặt trăng là yếu tố quan trọng để việc thực hiện tham vọng đưa con người lên sinh sống trên Mặt trăng có thể trở thành sự thực, bởi việc chuyên chở nước từ Trái đất lên quá tốn kém. Tuy nhiên, những quan sát gần đây bằng radar hành tinh Arecibo cho thấy một số dữ liệu thám sát radar của chương trình Clementine gần vùng cực trước kia được cho là dấu hiệu quả sự hiện diện của băng thực tế có thể chỉ là hậu quả từ những tảng đá được phun ra từ các núi lửa va chạm gần đây.[19] Câu hỏi về lượng nước thực sự có trên Mặt trăng vẫn chưa có lời giải đáp.

Các đặc điểm vật lý

Cấu trúc bên trong

Mặt trăng là một vật thể khác biệt, về mặt địa hoá học gồm một lớp vò, áo, và lõi. Cấu trúc này được cho là kết quả của sự kết tinh nứt gãy của một biển magma chỉ một thời gian ngắn sau khi nó hình thành khoảng 4.5 tỷ năm trước. Năng lượng cần thiết để làm tan chảy phần phía ngoài của Mặt trăng thường được cho là xuất phát từ một sự kiện va chạm lớn được cho là đã hình thành nên hệ thống Trái đất-Mặt trăng, và sự bồi đắp sau đó của vật chất trong quỹ đạo Trái đất. Sự kết tinh của biển magma khiếnxuất hiện áo mafic và một lớp vỏ giàu plagioclase (xem Nguồn gốc và tiến hoá địa chất bên dưới).

Việc vẽ bản đồ địa hoá học từ quỹ đạo cho thấy lớp vỏ Mặt trăng gồm phanà lớn thành phần là anorthositic,[20] phù hợp với giả thuyết biển magma. Về các nguyên tố, lớp vỏ gồm chủ yếu là oxy, silicon, magiê, sắt, canxi, và nhôm. Dựa trên các kỹ thuật địa vật lý, chiều dày của nó được ước tính trung bình khoảng 50 km.[21]

Sự tan chảy một phần bên trong lớp áo Mặt trăng khiến xuất hiện sự sụp đổ của biển basalt trên bề mặt Mặt trăng. Các phân tích basalt này cho thấy áo gồm chủ yếu là các khoáng chất olivine, orthopyroxene và clinopyroxene, và rằng áo mặt trăng có nhiều sắt hơn Trái đất. Một số basalt Mặt trăng chứa rất nhiều titan (hiện diện trong khoáng chất ilmenite), cho thấy áo sự không đồng nhất lớn trong thành phần. Các trận động đất trên Mặt trăng được phát hiện xảy ra sâu bên dưới lớp áo khoảng 1,000 km dưới bề mặt. Chúng diễn ra theo chu kỳ hàng tháng và liên quan tới các ứng suất thuỷ triều gây ra bởi quỹ đạo lệch tâm của Mặt trăng quanh Trái đất.[21]

Mặt trăng có mật độ trung bình 3,346.4 kg/m³, khiến nó trở thành mặt trăng có mật độ lớn thứ hai trong Hệ mặt trời sau Io. Tuy nhiên, nhiều bằng chứng cho thấy có thể lõi Mặt trăng nhỏ, với bán kính khoảng 350 km hay ít hơn.[21] Nó chỉ bằng khoảng 20% kích thước Mặt trăng, trái ngược so với 50% của đa số các thiên thể khác. Thành phần lõi Mặt trăng không đặc chắc, nhưng đa số mọi người tin rằng nó gồm lõi sắt với một lượng nhỏ sulfur và nickel. Các phân tích về sự khác biệt trong thời gian quay của Mặt trăng cho thấy ít nhất lõi Mặt trăng cũng nóng chảy một phần.[22]

Địa hình

Địa hình Mặt trăng đã được đo đạc bằng các biện pháp đo độ cao laser và phân tích hình stereo, đa số được thực hiện gần đây từ các dữ liệu thu thập được trong phi vụ Clementine. Đặc điểm địa hình dễ nhận thấy nhất là Vùng trũng Nam cực-Aitken phía bề mặt không nhìn thấy, nơi có những điểm thấp nhất của Mặt trăng. Các địa điểm cao nhất ở ngay phía đông bắc vùng trũng này, và nó cho thấy vùng này có thể có những trầm tích núi lửa phun dày đã xuất hiện trong sự kiện va chạm xiên vào vùng trũng Nam cực-Aitken. Các vùng trũng do va chạm lớn khác, như Imbrium, Serenitatis, Crisium, Smythii, và Orientale, cũng có địa hình vùng khá thấp và các gờ vòng tròn nổi. Một đặc điểm phân biệt khác của hình thể Mặt trăng là độ cao trung bình khoảng 1.9 km phía không nhìn thấy so với phía nhìn thấy.[21]

Trường hấp dẫn

Trường hấp dẫn của Mặt trăng đã được xác định qua việc thám sát các tín hiệu radio do các tàu vũ trụ bay trên quỹ đạo phát ra. Nguyên tắc sử dụng dựa trên Hiệu ứng Doppler, theo đó việc tàu vũ trụ tăng tốc theo hướng đường quan sát có thể được xác định bằng những thay đổi tăng nhỏ trong tần số tín hiệu radio, và khoảng cách từ tàu vũ trụ tới một trạm trên Trái đất. Tuy nhiên, vì sự quay đồng bộ của Mặt trăng vẫn không thể thám sát tàu vũ trụ vượt quá các rìa của Mặt trăng, và trường hấp dẫn phía bề mặt không nhìn thấy được vì thế vẫn còn chưa được biết rõ.[23]