Khác biệt giữa bản sửa đổi của “Kẽm”

→Ứng dụng: dịch |

|||

| Dòng 76: | Dòng 76: | ||

Với một thế điện cực chuẩn (SEP) 0,76 vôn, kẽm được sử dụng làm vật liệu anot cho pin. Bột kẽm được sử dụng theo cách này trong các loại pin kiềm và các tấm kẽm kim loại tạo thành vỏ bọc và cũng là anot trong pin kẽm-carbon.<ref>{{Cite book|first=Jürgen O.|last=Besenhard|title=Handbook of Battery Materials|accessdate=2008-10-08|publisher=Wiley-VCH|url=http://www.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/tocs/60178752.pdf|isbn=3-527-29469-4|year=1999}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|doi=10.1016/0378-7753(95)02242-2|year=1995|title=Recycling zinc batteries: an economical challenge in consumer waste management|first=J. -P.|last=Wiaux|coauthors=Waefler, J. -P.|journal=Journal of Power Sources|volume=57|issue=1–2|page=61}}</ref> Kẽm được sử dụng làm anot hoặc nhiên liệu cho tế bào nhiêu liệu kẽm/pin kẽm-không khí.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=A design guide for rechargeable zinc-air battery technology|last=Culter|first=T.|doi=10.1109/SOUTHC.1996.535134|journal=Southcon/96. Conference Record|isbn=0-7803-3268-7|year=1996|page=616}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.electric-fuel.com/evtech/papers/paper11-1-98.pdf| title=Zinc Air Battery-Battery Hybrid for Powering Electric Scooters and Electric Buses|first=Jonathan|last=Whartman|coauthors=Brown, Ian|publisher=The 15th International Electric Vehicle Symposium| accessdate=2008-10-08}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url =http://www.osti.gov/energycitations/product.biblio.jsp?osti_id=82465|title=A refuelable zinc/air battery for fleet electric vehicle propulsion|last=Cooper|first=J. F|coauthors=Fleming, D.; Hargrove, D.; Koopman, R.; Peterman, K|publisher=Society of Automotive Engineers future transportation technology conference and exposition|accessdate=2008-10-08}}</ref> |

Với một thế điện cực chuẩn (SEP) 0,76 vôn, kẽm được sử dụng làm vật liệu anot cho pin. Bột kẽm được sử dụng theo cách này trong các loại pin kiềm và các tấm kẽm kim loại tạo thành vỏ bọc và cũng là anot trong pin kẽm-carbon.<ref>{{Cite book|first=Jürgen O.|last=Besenhard|title=Handbook of Battery Materials|accessdate=2008-10-08|publisher=Wiley-VCH|url=http://www.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/tocs/60178752.pdf|isbn=3-527-29469-4|year=1999}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|doi=10.1016/0378-7753(95)02242-2|year=1995|title=Recycling zinc batteries: an economical challenge in consumer waste management|first=J. -P.|last=Wiaux|coauthors=Waefler, J. -P.|journal=Journal of Power Sources|volume=57|issue=1–2|page=61}}</ref> Kẽm được sử dụng làm anot hoặc nhiên liệu cho tế bào nhiêu liệu kẽm/pin kẽm-không khí.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=A design guide for rechargeable zinc-air battery technology|last=Culter|first=T.|doi=10.1109/SOUTHC.1996.535134|journal=Southcon/96. Conference Record|isbn=0-7803-3268-7|year=1996|page=616}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.electric-fuel.com/evtech/papers/paper11-1-98.pdf| title=Zinc Air Battery-Battery Hybrid for Powering Electric Scooters and Electric Buses|first=Jonathan|last=Whartman|coauthors=Brown, Ian|publisher=The 15th International Electric Vehicle Symposium| accessdate=2008-10-08}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url =http://www.osti.gov/energycitations/product.biblio.jsp?osti_id=82465|title=A refuelable zinc/air battery for fleet electric vehicle propulsion|last=Cooper|first=J. F|coauthors=Fleming, D.; Hargrove, D.; Koopman, R.; Peterman, K|publisher=Society of Automotive Engineers future transportation technology conference and exposition|accessdate=2008-10-08}}</ref> |

||

{{Đang dịch 2 (nguồn)|ngày=4 |

|||

|tháng=04 |

|||

|năm=2013 |

|||

|1 = |

|||

}} |

|||

===Hợp kim=== |

|||

A widely used alloy which contains zinc is brass, in which copper is alloyed with anywhere from 3% to 45% zinc, depending upon the type of brass.<ref name="Lehto1968p829"/> Brass is generally more [[ductile]] and stronger than copper and has superior [[corrosion resistance]].<ref name="Lehto1968p829"/> These properties make it useful in communication equipment, hardware, musical instruments, and water valves.<ref name="Lehto1968p829"/> |

|||

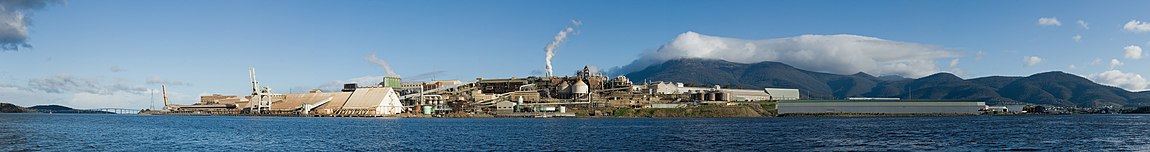

[[File:Macrostructure of rolled and annealed brass; magnification 400X.jpg|thumb|left|Cast brass microstructure at magnification 400x|alt=A mosaica pattern composed of components having various shapes and shades of brown.]] |

|||

Other widely used alloys that contain zinc include [[nickel silver]], typewriter metal, soft and aluminium [[solder]], and commercial [[bronze]].<ref name="CRCp4-41"/> Zinc is also used in contemporary pipe organs as a substitute for the traditional lead/tin alloy in pipes.<ref>{{Cite book|first=Douglas Earl|last=Bush|coauthor=Kassel, Richard|title=The Organ: An Encyclopedia|isbn=978-0-415-94174-7|url=http://books.google.com/?id=cgDJaeFFUPoC|publisher=Routledge|year=2006|page=679}}</ref> Alloys of 85–88% zinc, 4–10% copper, and 2–8% aluminium find limited use in certain types of machine bearings. Zinc is the primary metal used in making [[Lincoln cent|American one cent coins]] since 1982.<ref name="onecent">{{cite web|url=http://www.usmint.gov/about_the_mint/?action=coin_specifications|publisher=United States Mint|accessdate=2008-10-08|title=Coin Specifications}}</ref> The zinc core is coated with a thin layer of copper to give the impression of a copper coin. In 1994, {{convert|33200|t|ST}} of zinc were used to produce 13.6 billion pennies in the United States.<ref name="USGS-yb1994">{{cite web|url=http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/zinc/720494.pdf|publisher=United States Geological Survey|title=Mineral Yearbook 1994: Zinc|first=Stephen M|last=Jasinski|accessdate=2008-11-13}}</ref> |

|||

Alloys of primarily zinc with small amounts of copper, aluminium, and magnesium are useful in [[die casting]] as well as [[spin casting]], especially in the automotive, electrical, and hardware industries.<ref name="CRCp4-41"/> These alloys are marketed under the name [[Zamak]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.eazall.com/diecastalloys.aspx|title=Diecasting Alloys|author=Eastern Alloys contributors|publisher=Eastern Alloys|accessdate=2009-01-19|location=Maybrook, NY}}</ref> An example of this is [[zinc aluminium]]. The low melting point together with the low [[viscosity]] of the alloy makes the production of small and intricate shapes possible. The low working temperature leads to rapid cooling of the cast products and therefore fast assembly is possible.<ref name="CRCp4-41"/><ref>{{Cite journal|first=D.|last=Apelian|coauthors=Paliwal, M.; Herrschaft, D. C.|title=Casting with Zinc Alloys|journal=Journal of Metals|volume=33|year=1981|pages =12–19}}</ref> Another alloy, marketed under the brand name Prestal, contains 78% zinc and 22% aluminium and is reported to be nearly as strong as steel but as malleable as plastic.<ref name="CRCp4-41"/><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://books.google.com/?id=s0i32LSfrJ4C&pg=PA157|page=157|title=Materials for automobile bodies|author=Davies, Geoff|publisher=Butterworth-Heinemann|year=2003|isbn=0-7506-5692-1}}</ref> This [[superplasticity]] of the alloy allows it to be molded using die casts made of ceramics and cement.<ref name="CRCp4-41"/> |

|||

Similar alloys with the addition of a small amount of lead can be cold-rolled into sheets. An alloy of 96% zinc and 4% aluminium is used to make stamping dies for low production run applications for which ferrous metal dies would be too expensive.<ref name="samans">{{Cite book|last=Samans|first=Carl Hubert|title=Engineering Metals and Their Alloys|publisher=Macmillan Co|year=1949}}</ref> In building facades, roofs or other applications in which zinc is used as [[sheet metal]] and for methods such as [[deep drawing]], [[roll forming]] or [[bending (metalworking)|bending]], zinc alloys with [[titanium]] and copper are used.<ref name="ZincCorr">{{Cite book|url=http://books.google.com/?id=C-pAiedmqp8C|title=Corrosion Resistance of Zinc and Zinc Alloys|first=Frank|last=Porter|publisher =CRC Press|year=1994|isbn=978-0-8247-9213-8|chapter=Wrought Zinc|pages=6–7}}</ref> Unalloyed zinc is too brittle for these kinds of manufacturing processes.<ref name="ZincCorr"/> |

|||

As a dense, inexpensive, easily worked material, zinc is used as a [[lead]] replacement. In the wake of [[Lead poisoning|lead concerns]], zinc appears in weights for various applications ranging from fishing<ref>{{cite book|author=McClane, Albert Jules and Gardner, Keith |title=The Complete book of fishing: a guide to freshwater, saltwater & big-game fishing|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=b3nWAAAAMAAJ|accessdate=26 June 2012|year=1987|publisher=Gallery Books|isbn=978-0-8317-1565-6}}</ref> to [[tire balance]]s and flywheels.<ref name="minrecall">{{cite web | url=http://www.minourausa.com/english/support-e/recall-e.html |

|||

| title=Cast flywheel on old Magturbo trainer has been recalled since July 2000|work=Minoura}}</ref> |

|||

[[Cadmium zinc telluride]] (CZT) is a [[semiconductor|semiconductive]] alloy that can be divided into an array of small sensing devices.<ref name="Katz2002"/> These devices are similar to an [[integrated circuit]] and can detect the energy of incoming [[gamma ray]] photons.<ref name="Katz2002"/> When placed behind an absorbing mask, the CZT sensor array can also be used to determine the direction of the rays.<ref name="Katz2002">{{Cite book| title=The Biggest Bangs|last=Katz|first=Johnathan I.|page=18|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|year=2002|isbn=0-19-514570-4}}</ref> |

|||

===Các ứng dụng công nghiệp khác=== |

|||

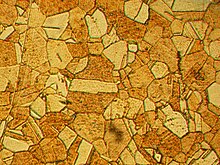

[[File:Zinc oxide.jpg|thumb|Zinc oxide is used as a white [[pigment]] in [[paint]]s.|alt=White powder on a glass plate]] |

|||

Roughly one quarter of all zinc output in the United States (2009), is consumed in the form of zinc compounds;<ref name="USGS-yb2006"/> a variety of which are used industrially. Zinc oxide is widely used as a white pigment in paints, and as a [[catalyst]] in the manufacture of rubber. It is also used as a heat disperser for the rubber and acts to protect its polymers from [[ultraviolet radiation]] (the same UV protection is conferred to plastics containing zinc oxide).<ref name="Emsley2001p503"/> The [[semiconductor]] properties of zinc oxide make it useful in [[varistor]]s and photocopying products.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Zhang|first=Xiaoge Gregory|title=Corrosion and Electrochemistry of Zinc|publisher=Springer|year=1996|page=93|isbn=0-306-45334-7|url=http://books.google.com/?id=Qmf4VsriAtMC}}</ref> The [[zinc zinc-oxide cycle]] is a two step [[Thermochemistry|thermochemical]] process based on zinc and zinc oxide for [[hydrogen production]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/pdfs/review06/pd_10_weimer.pdf|title=Development of Solar-powered Thermochemical Production of Hydrogen from Water|last=Weimer|first=Al|date=2006-05-17|accessdate=2009-01-10|publisher=[[U.S. Department of Energy]]}}</ref> |

|||

[[Zinc chloride]] is often added to lumber as a [[fire retardant]]<ref name="Heiserman1992p124">{{harvnb|Heiserman|1992|p=124}}</ref> and can be used as a wood [[preservative]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Wood preservatives|last=Blew|first=Joseph Oscar|year=1953|publisher=Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory|url=http://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1957/816/FPL_D149ocr.pdf|id={{hdl|1957/816}}}}</ref> It is also used to make other chemicals.<ref name="Heiserman1992p124"/> [[Zinc methyl]] ({{chem|Zn(CH<sub>3</sub>)|2}}) is used in a number of organic [[organic synthesis|syntheses]].<ref>{{Cite journal|first=Edward|last=Frankland|authorlink=Edward Frankland|journal=[[Liebigs Annalen|Liebig's Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie]]|title=Notiz über eine neue Reihe organischer Körper, welche Metalle, Phosphor u. s. w. enthalten|year=1849|volume=71|issue=2|page=213|doi=10.1002/jlac.18490710206|language=German}}</ref> [[Zinc sulfide]] (ZnS) is used in [[luminescence|luminescent]] pigments such as on the hands of clocks, [[X-ray]] and television screens, and [[luminous paint]]s.<ref name="CRCp4-42">{{harvnb|CRC|2006|p='''4'''-42<!-- sic "hyphen -" ; not a range!-->}}</ref> Crystals of ZnS are used in [[laser]]s that operate in the mid-[[infrared]] part of the spectrum.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Paschotta|first=Rüdiger|title=Encyclopedia of Laser Physics and Technology|publisher=Wiley-VCH|year=2008|page=798|isbn=3-527-40828-2|url=http://books.google.com/?id=BN026ye2fJAC}}</ref> [[Zinc sulfate]] is a chemical in [[dye]]s and pigments.<ref name="Heiserman1992p124"/> [[Zinc pyrithione]] is used in [[antifouling]] paints.<ref>{{Cite journal|journal=Environment International|volume=30|year=2004|issue=2|page=235|doi=10.1016/S0160-4120(03)00176-4|title=Worldwide occurrence and effects of antifouling paint booster biocides in the aquatic environment: a review|first=I. K.|last=Konstantinou|coauthors=Albanis, T. A.}}</ref> |

|||

Zinc powder is sometimes used as a [[propellant]] in [[model rocket]]s.<ref name="ZnS"/> When a compressed mixture of 70% zinc and 30% [[sulfur]] powder is ignited there is a violent chemical reaction.<ref name="ZnS"/> This produces zinc sulfide, together with large amounts of hot gas, heat, and light.<ref name="ZnS">{{cite web|url=http://www.angelo.edu/faculty/kboudrea/demos/zinc_sulfur/zinc_sulfur.htm|title=Zinc + Sulfur|last=Boudreaux|first=Kevin A|publisher=Angelo State University|accessdate=2008-10-08}}</ref> Zinc sheet metal is used to make zinc [[bar (counter)|bars]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Technical Information|year=2008|publisher=Zinc Counters| url=http://www.zinccounters.co.uk/html/tech/tech.htm|accessdate=2008-11-29}}</ref> |

|||

{{chem|64|Zn}}, the most abundant isotope of zinc, is very susceptible to [[neutron activation]], being [[Nuclear transmutation|transmuted]] into the highly radioactive {{chem|65|Zn}}, which has a half-life of 244 days and produces intense [[gamma ray|gamma radiation]]. Because of this, Zinc Oxide used in nuclear reactors as an anti-corrosion agent is depleted of {{chem|64|Zn}} before use, this is called [[depleted zinc oxide]]. For the same reason, zinc has been proposed as a [[Salted bomb|salting]] material for [[nuclear weapon]]s ([[cobalt]] is another, better-known salting material).<ref name="Win2003"/> A jacket of [[Isotope separation|isotopically enriched]] {{chem|64|Zn}} would be irradiated by the intense high-energy neutron flux from an exploding thermonuclear weapon, forming a large amount of {{chem|65|Zn}} significantly increasing the radioactivity of the weapon's [[Nuclear fallout|fallout]].<ref name="Win2003"/> Such a weapon is not known to have ever been built, tested, or used.<ref name="Win2003">{{Cite journal|title=Weapons of Mass Destruction|first=David Tin|last=Win|coauthors=Masum, Al|url=http://www.journal.au.edu/au_techno/2003/apr2003/aujt6-4_article07.pdf|year=2003|journal=Assumption University Journal of Technology|volume=6|issue=4|page=199|publisher=Assumption University|accessdate=2009-04-06}}</ref> {{chem|65|Zn}} is also used as a [[isotopic tracer|tracer]] to study how alloys that contain zinc wear out, or the path and the role of zinc in organisms.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3427000114.html|isbn=0-7876-2846-8|publisher=U. X. L. /Gale|year=1999|title=Chemical Elements: From Carbon to Krypton|author=David E. Newton|accessdate=2009-04-06}}</ref> |

|||

Zinc dithiocarbamate complexes are used as agricultural [[fungicide]]s; these include [[Zineb]], Metiram, Propineb and Ziram.<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://books.google.com/?id=cItuoO9zSjkC&pg=PA591|title=Ullmann's Agrochemicals|year=2007|publisher=Wiley-Vch (COR)|isbn=3-527-31604-3|pages=591–592}}</ref> Zinc naphthenate is used as wood preservative.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Primary Wood Processing: Principles and Practice| last=Walker|first =J. C. F.|year=2006|publisher=Springer|isbn=1-4020-4392-9|page=317}}</ref> Zinc, in the form of [[Zinc dithiophosphate|ZDDP]], is also used as an anti-wear additive for metal parts in engine oil.<ref>{{cite web|title=ZDDP Engine Oil – The Zinc Factor|url=http://www.mustangmonthly.com/techarticles/mump_0907_zddp_zinc_additive_engine_oil/index.html|publisher=Mustang Monthly|accessdate=2009-09-19}}</ref> |

|||

===Bổ sung trong khẩu phần ăn=== |

|||

[[File:Zinc 50 mg.jpg|thumb|175px|[[General Nutrition Centers|GNC]] zinc 50 mg tablets ([[Australia|AU]])]] |

|||

Zinc is included in most single tablet over-the-counter daily vitamin and [[Dietary mineral|mineral]] supplements.<ref name="DiSilvestro2004">{{Cite book|last=DiSilvestro|first=Robert A.|title=Handbook of Minerals as Nutritional Supplements|year=2004|publisher=CRC Press|pages=135, 155|isbn=0-8493-1652-9}}</ref> Preparations include zinc oxide, zinc acetate, and [[zinc gluconate]].<ref name="DiSilvestro2004"/> It is believed to possess [[antioxidant]] properties, which may protect against accelerated aging of the skin and muscles of the body; studies differ as to its effectiveness.<ref name="Milbury2008">{{Cite book|last=Milbury|first=Paul E.|coauthors=Richer, Alice C.| title=Understanding the Antioxidant Controversy: Scrutinizing the "fountain of Youth"|page=99|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group|isbn=0-275-99376-0|year=2008}}</ref> Zinc also helps speed up the healing process after an injury.<ref name="Milbury2008"/> It is also beneficial to the body's immune system. Indeed, zinc deficiency may have effects on virtually all parts of the human immune system.<ref>{{cite journal|pmid=2200472|year=1990|last1=Keen|first1=CL|last2=Gershwin|first2=ME|title=Zinc deficiency and immune function|volume=10|pages=415–31|doi=10.1146/annurev.nu.10.070190.002215|journal=Annual review of nutrition}}</ref> |

|||

The efficacy of zinc compounds when used to reduce the duration or severity of [[Common cold|cold]] symptoms is [[Alternative treatments used for the common cold#Zinc preparations|controversial]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Zinc and Health : The Common Cold |url=http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/zinc/#h7 |publisher=Office of Dietary Supplements, [[National Institutes of Health]] |accessdate=2010-05-01}}</ref> A 2011 [[systematic review]] concludes that supplementation yields a mild decrease in duration and severity of cold symptoms.<ref>{{Cite journal| author=Singh M, Das RR.| title=Zinc for the common cold|journal=Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews| year=2011| issue=2| doi=10.1002/14651858.CD001364.pub3| pmid=21328251| volume=2| pages=CD001364| editor1-last=Singh| editor1-first=Meenu}}</ref> |

|||

Zinc serves as a simple, inexpensive, and critical tool for treating diarrheal episodes among children in the developing world. Zinc becomes depleted in the body during [[diarrhea]], but recent studies suggest that replenishing zinc with a 10- to 14-day course of treatment can reduce the duration and severity of diarrheal episodes and may also prevent future episodes for up to three months.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Therapeutic effects of oral zinc in acute and persistent diarrhea in children in developing countries: pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials|pmid=11101480|year=2000|last1=Bhutta|first1=ZA|last2=Bird|first2=SM|last3=Black|first3=RE|last4=Brown|first4=KH|last5=Gardner|first5=JM|last6=Hidayat|first6=A|last7=Khatun|first7=F|last8=Martorell|first8=R|last9=Ninh|first9=NX|volume=72|issue=6|pages=1516–22|journal=The American journal of clinical nutrition}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Zinc gluconate structure.svg|thumb|left|[[Zinc gluconate]] is one compound used for the delivery of zinc as a [[dietary supplement]].|alt=Skeletal chemical formula of a planar compound featuring a Zn atom in the center, symmetrically bonded to four oxygens. Those oxygens are further connected to linear COH chains.]] |

|||

The [[Age-Related Eye Disease Study]] determined that zinc can be part of an effective treatment for [[age-related macular degeneration]].<ref>{{Cite journal|title=A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Clinical Trial of High-Dose Supplementation With Vitamins C and E, Beta Carotene, and Zinc for Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Vision Loss: AREDS Report No. 8|author=Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group|journal=Arch Ophthalmology|year=2001|volume=119|issue=10|pmid=11594942|pmc=1462955|pages=1417–36|doi=10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417}}</ref> Zinc supplementation is an effective treatment for [[acrodermatitis enteropathica]], a genetic disorder affecting zinc absorption that was previously fatal to babies born with it.<ref name="Emsley2001p501"/> |

|||

[[Gastroenteritis]] is strongly attenuated by ingestion of zinc, and this effect could be due to direct antimicrobial action of the zinc ions in the [[gastrointestinal tract]], or to the absorption of the zinc and re-release from immune cells (all [[granulocyte]]s secrete zinc), or both.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Aydemir|first=T. B.|coauthor=Blanchard, R. K.; Cousins, R. J.|year=2006|title=Zinc supplementation of young men alters metallothionein, zinc transporter, and cytokine gene expression in leukocyte populations|journal=PNAS|pmid=16434472|volume=103|issue=6|pmc=1413653|doi=10.1073/pnas.0510407103|bibcode = 2006PNAS..103.1699A|pages=1699–704 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Valko|first=M.|coauthors=Morris, H.; Cronin, M. T. D.|year=2005|title=Metals, Toxicity and Oxidative stress|journal=Current Medicinal Chemistry|issue=10|volume=12|doi=10.2174/0929867053764635|pmid=15892631|pages=1161–208}}</ref><ref group=note>In [[clinical trial]]s, both zinc gluconate and zinc gluconate glycine (the formulation used in lozenges) have been shown to shorten the duration of symptoms of the common cold. |

|||

:{{cite journal|last=Godfrey|first=J. C.|coauthors=Godfrey, N. J.; Novick, S. G.|title=Zinc for treating the common cold: Review of all clinical trials since 1984|year=1996|pmid=8942045|journal=Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine|volume=2|issue=6|pages=63–72}} |

|||

The amount of glycine can vary from two to twenty moles per mole of zinc gluconate. One review of the research found that out of nine controlled experiments using zinc lozenges, the results were positive in four studies, and no better than placebo in five. |

|||

:{{cite web|url=http://web.archive.org/web/20081222105854/http://www.uspharmacist.com/oldformat.asp?url=newlook/files/alte/feat2.htm| work=US Pharmacist|title=Zinc and the Common Cold: What Pharmacists Need to Know|last=Hulisz|first=Darrell T|publisher=uspharmacist.com|accessdate=2012-04-09}} |

|||

This review also suggested that the research is characterized by methodological problems, including differences in the dosage amount used, and the use of self-report data. The evidence suggests that zinc supplements may be most effective if they are taken at the first sign of cold symptoms.</ref> |

|||

In 2011, researchers at [[John Jay College of Criminal Justice]] reported that dietary zinc supplements can mask the presence of drugs in urine. Similar claims have been made in web forums on that topic.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Venkatratnam|first=Abhishek|coauthors=Nathan Lents|title=Zinc Reduces the Detection of Cocaine, Methamphetamine, and THC by ELISA Urine Testing|journal=Journal of Analytical Toxicology|date=1 July 2011|volume=35|issue=6|pages=333–340|pmid=21740689|url=http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/pres/jat/2011/00000035/00000006/art00002|doi=10.1093/anatox/35.6.333}}</ref> |

|||

Although not yet tested as a therapy in humans, a growing body of evidence indicates that zinc may preferentially kill prostate cancer cells. Because zinc naturally homes to the prostate and because the prostate is accessible with relatively non-invasive procedures, its potential as a chemotherapeutic agent in this type of cancer has shown promise.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Shah|first=Maulik|coauthors=Christopher Kriedt, Nathan H. Lents, Mary K. Hoyer, Nimah Jamaluddin, Claudette Kelin, Joseph J. Baldassare|title=Direct intra-tumoral injection of zinc-acetate halts tumor growth in a xenograft model of prostate cancer|journal=Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research|date=17|year=2009|month=June|volume=28|issue=84|doi=10.1186/1756-9966-28-84|pmid=19534805|url=http://www.jeccr.com/content/28/1/84|page=84|pmc=2701928}}</ref> However, other studies have demonstrated that chronic use of zinc supplements in excess of the recommended dosage may actually increase the chance of developing prostate cancer, also likely due to the natural buildup of this heavy metal in the prostate.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1093/jnci/95.13.1004|url=http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/95/13/1004.short|title=Zinc Supplement Use and Risk of Prostate Cancer|year=2003|last1=Leitzmann|first1=M. F.|last2=Stampfer|first2=M. J.|last3=Wu|first3=K.|last4=Colditz|first4=G. A.|last5=Willett|first5=W. C.|last6=Giovannucci|first6=E. L.|journal=JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute|volume=95|issue=13|page=1004}}</ref> |

|||

===Dùng làm thuốc ngoài da=== |

|||

{{further|Zinc oxide#Medical}} |

|||

[[Topical administration]] of zinc preparations include ones used on the skin, often in the form of [[zinc oxide]]. Zinc preparations can protect against [[sunburn]] in the summer and [[windburn]] in the winter.<ref name="Emsley2001p501"/> Applied thinly to a baby's diaper area ([[perineum]]) with each diaper change, it can protect against [[diaper rash]].<ref name="Emsley2001p501"/> |

|||

Zinc lactate is used in toothpaste to prevent [[halitosis]].<ref>{{Cite journal|volume =30|issue =5|page=427|year=2003|title=The effects of a new mouthrinse containing chlorhexidine, cetylpyridinium chloride and zinc lactate on the microflora of oral halitosis patients: a dual-centre, double-blind placebo-controlled study|author=Roldán, S.; Winkel, E. G.; Herrera, D.; Sanz, M.; Van Winkelhoff, A. J.|doi=10.1034/j.1600-051X.2003.20004.x|journal =Journal of Clinical Periodontology}}</ref> [[Zinc pyrithione]] is widely applied in shampoos because of its anti-dandruff function.<ref>{{cite journal|journal=British Journal of Dermatology|volume=112|issue=4|page=415|title=The effects of a shampoo containing zinc pyrithione on the control of dandruff|first=R.|last=Marks|coauthors=Pearse, A. D.; Walker, A. P.|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02314.x|year=1985}}</ref> |

|||

Zinc ions are effective [[antimicrobial agent]]s even at low concentrations.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=McCarthy|first=T J|coauthors=Zeelie, J J: Krause, D J|date=1992 Feb|title=The antimicrobial action of zinc ion/antioxidant combinations|journal=Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics|publisher=American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics|volume=17|issue=1|page=5}}</ref> |

|||

===Hóa hữu cơ=== |

|||

[[Image:DiphenylzincCarbonylAddition.png|thumb|350px|Addition of diphenylzinc to an aldehyde]] |

|||

There are many important [[organozinc compounds]]. Organozinc chemistry is the science of organozinc compounds describing their physical properties, synthesis and reactions.<ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1002/0471264180.or066.01 | chapter = The Allylic Trihaloacetimidate Rearrangement | title = Organic Reactions | year = 2005 | last1 = Overman | first1 = Larry E. | last2 = Carpenter | first2 = Nancy E. | isbn = 0-471-26418-0 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | isbn = 0-470-09337-4| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=Y3wYEmIHlqUC | title = The Chemistry of Organozinc Compounds: R-Zn | author1 = Rappoport | first1 = Zvi | last2 = Marek | first2 = Ilan | date = 2007-12-17}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | isbn = 0-19-850121-8 | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=UH5tQgAACAAJ | title = Organozinc reagents: A practical approach | author1 = Knochel | first1 = Paul | last2 = Jones | first2 = Philip | year = 1999}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=hgUqZkG23PAC| isbn = 3-13-103061-5 | title = Synthetic Methods of Organometallic and Inorganic Chemistry: Catalysis | author1 = Herrmann | first1 = Wolfgang A | date = 2002-01}}</ref> |

|||

Among important applications is the Frankland-Duppa Reaction in which an [[oxalate]] [[ester]](ROCOCOOR) reacts with an [[alkyl halide]] R'X, zinc and [[hydrochloric acid]] to the α-hydroxycarboxylic esters RR'COHCOOR,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.drugfuture.com/OrganicNameReactions/ONR144.htm|title=Frankland-Duppa Reaction|accessdate=2012-02-13}}</ref> the [[Reformatskii reaction]] which converts α-halo-esters and aldehydes to β-hydroxy-esters, the [[Simmons–Smith reaction]] in which the carbenoid (iodomethyl)zinc iodide reacts with alkene(or alkyne) and converts them to cyclopropane, the [[Addition reaction]] of organozinc compounds to [[carbonyl]] compounds. The [[Barbier reaction]] (1899) which is the zinc equivalent of the magnesium [[Grignard reaction]] and is better of the two. In presence of just about any water the formation of the organomagnesium halide will fail whereas the Barbier reaction can even take place in water. On the downside organozincs are much less nucleophilic than Grignards, are expensive and difficult to handle. Commercially available diorganozinc compounds are [[dimethylzinc]], [[diethylzinc]] and diphenylzinc. In one study<ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1002/anie.200600741 | title = From Aryl Bromides to Enantioenriched Benzylic Alcohols in a Single Flask: Catalytic Asymmetric Arylation of Aldehydes | year = 2006 | last1 = Kim | first1 = Jeung Gon | last2 = Walsh | first2 = Patrick J. | journal = Angewandte Chemie International Edition | volume = 45 | issue = 25 | pages = 4175}}</ref><ref>In this [[one-pot reaction]] [[bromobenzene]] is converted to [[phenyllithium]] by reaction with 4 equivalents of [[N-Butyllithium|''n''-butyllithium]], then transmetalation with [[zinc chloride]] forms diphenylzinc which continues to react in an [[asymmetric reaction]] first with the [[MIB ligand]] and then with 2-naphthylaldehyde to the [[alcohol]]. In this reaction formation of diphenylzinc is accompanied by that of [[lithium chloride]], which unchecked, catalyses the reaction without MIB involvement to the [[racemic]] [[alcohol]]. The salt is effectively removed by [[chelation]] with [[tetraethylethylene diamine]] (TEEDA) resulting in an [[enantiomeric excess]] of 92%.</ref> the active organozinc compound is obtained from much cheaper [[organobromine compound|organobromine]] precursors: |

|||

The [[Negishi coupling]] is also an important reaction for the formation of new carbon carbon bonds between unsaturated carbon atoms in alkenes, arenes and alkynes. The catalysts are nickel and palladium. A key step in the [[catalytic cycle]] is a [[transmetalation]] in which a zinc halide exchanges its organic substituent for another halogen with the palladium (nickel) metal center. The [[Fukuyama coupling]] is another coupling reaction but this one with a thioester as reactant forming a ketone. |

|||

<!-- NEEDS CITE |

|||

Organozinc compounds usually contain zinc in +2 oxidation state, but compounds in +1 state are also known such as [[decamethyldizincocene]]. --> |

|||

=== Hợp chất === |

=== Hợp chất === |

||

Phiên bản lúc 14:37, ngày 4 tháng 4 năm 2013

| Kẽm, 30Zn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Các mảnh và khối kẽm với độ tinh khiết 99,995% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Quang phổ vạch của kẽm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tính chất chung | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tên, ký hiệu | Kẽm, Zn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hình dạng | Ánh kim bạc xám | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kẽm trong bảng tuần hoàn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Số nguyên tử (Z) | 30 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khối lượng nguyên tử chuẩn (±) (Ar) | 65,38(2)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phân loại | kim loại chuyển tiếp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nhóm, phân lớp | 12, d | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chu kỳ | Chu kỳ 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cấu hình electron | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

mỗi lớp | 2, 8, 18, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tính chất vật lý | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Màu sắc | Ánh kim bạc xám | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trạng thái vật chất | Chất rắn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nhiệt độ nóng chảy | 692,68 K (419,53 °C, 787,15 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nhiệt độ sôi | 1.180 K (907 °C, 1.665 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mật độ | 7,14 g·cm−3 (ở 0 °C, 101.325 kPa) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mật độ ở thể lỏng | ở nhiệt độ nóng chảy: 6,57 g·cm−3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nhiệt lượng nóng chảy | 7,32 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nhiệt bay hơi | 123,6 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nhiệt dung | 25,470 J·mol−1·K−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Áp suất hơi

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tính chất nguyên tử | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trạng thái oxy hóa | 2, 1, 0, -2 Lưỡng tính | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Độ âm điện | 1,65 (Thang Pauling) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Năng lượng ion hóa | Thứ nhất: 906,4 kJ·mol−1 Thứ hai: 1.733,3 kJ·mol−1 Thứ ba: 3.833 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bán kính cộng hoá trị | thực nghiệm: 134 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bán kính liên kết cộng hóa trị | 122±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bán kính van der Waals | 139 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thông tin khác | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cấu trúc tinh thể | Lục phương | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vận tốc âm thanh | que mỏng: (Cuộn dây) 3850 m·s−1 (ở r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Độ giãn nở nhiệt | 30,2 µm·m−1·K−1 (ở 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Độ dẫn nhiệt | 116 W·m−1·K−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Điện trở suất | ở 20 °C: 59,0 n Ω·m | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tính chất từ | Nghịch từ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mô đun Young | 108 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mô đun cắt | 43 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mô đun khối | 70 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hệ số Poisson | 0,25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Độ cứng theo thang Mohs | 2,5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Độ cứng theo thang Brinell | 412 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Số đăng ký CAS | 7440-66-6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Đồng vị ổn định nhất | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bài chính: Đồng vị của Kẽm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Kẽm là một nguyên tố kim loại lưỡng tính, kí hiệu là Zn và có số nguyên tử là 30. Nó là nguyên tố đầu tiên trong nhóm 12 của bảng tuần hoàn nguyên tố. Kẽm, trên một số phương diện, có tính chất hóa học giống với magiê, vì ion của chúng có bán kính giống nhau và có trạng thái oxi hóa duy nhất ở điều kiện bình thường là +2. Kẽm là nguyên tố phổ biến thứ 24 trong lớp vỏ Trái Đất và có 5 đồng vị bền. Quặng kẽm phổ biến nhất là quặng sphalerit, một loại sulfua kẽm. Những mỏ khai thác lớn nhất nằm ở Úc, Canada và Hoa Kỳ. Công nghệ sản xuất kẽm bao gồm tuyển nổi quặng, thiêu kết, và cuối cùng là chiết tách bằng dòng điện.

Đồng thau là một hợp kim của đồng và kẽm đã bắt đầu được sử dụng muộn nhất từ thế kỷ 10 TCN. Mãi cho đến thế kỷ 13 thì kẽm nguyên chất mới được sản xuất quy mô lớn ở Ấn Độ, và đến cuối thế kỷ 16 thì người châu Âu mới biết đến kẽm kim loại. Các nhà giả kim thuật đốt kẽm trong không khí để tạo thành một chất mà họ gọi là "len của nhà triết học" hay "tuyết trắng". Nhà hóa học người Đức Andreas Sigismund Marggraf được công nhận đã tách được kẽm kim loại tinh khiết năm 1746. Luigi Galvani và Alessandro Volta đã phát hiện ra các đặc tính hóa điện của kẽm năm vào 1800. Ứng dụng chính của kẽm là làm lớp phủ chống ăn mòn trên thép. Các ứng dụng khác như làm pin kẽm, và hợp kim như đồng thau. Nhiều hợp chất kẽm cũng được sử dụng phổ biến như kẽm cacbonat và kẽm gluconat (bổ sung dinh dưỡng), kẽm clorua (chất khử mùi), kẽm pyrithion (dầu gội đầu trị gàu), kẽm sulfua (sơn huỳnh quang), và kẽm methyl hay kẽm diethyl sử dụng trong hóa hữu cơ ở phòng thí nghiệm.

Kẽm là một chất khoáng vi lượng thiết yếu cho sinh vật và sức khỏe con người.[4] Thiếu kẽm ảnh hưởng đến khoảng 2 tỷ người ở các nước đang phát triển và liên quan đến nguyên nhân một số bệnh.[5] Ở trẻ em, thiếu kẽm gây ra chứng chậm phát triển, phát dục trễ, dễ nhiễm trùng và tiêu chảy, các yếu tố này gây thiệt mạng khoảng 800.000 trẻ em trên toàn thế giới mỗi năm.[4] Các enzym liên kết với kẽm trong trung tâm phản ứng có vai trò sinh hóa quan trọng như alcohol dehydrogenase ở người. Ngược lại việc tiêu thụ quá mức kẽm có thể gây ra một số chứng như hôn mê, bất động cơ và thiếu đồng.

Tính chất

Kẽm là một kim loại hoạt động trung bình có thể kết hợp với ôxy và các á kim khác, có phản ứng với axít loãng để giải phóng hiđrô. Trạng thái ôxi hóa phổ biến của kẽm là +2.

Vật lý

Kẽm có màu trắng xanh, óng ánh và nghịch từ,[6] mặc dù hầu hết kẽm phẩm cấp thương mại có màu xám xỉn.[7] Nó hơi nhẹ hơn sắt và có cấu trúc tinh thể sáu phương.[8]

Kẽm kim loại cứng và giòn ở hầu hết cấp nhiệt độ nhưng trở nên dễ uốn từ 100 đến 150 °C.[6][7] Trên 210 °C, kim loại kẽm giòn trở lại và có thể được tán nhỏ bằng lực.[9] Kẽm dẫn điện khá.[6] So với các kim loại khác, kẽm có độ nóng chảy (419,5 °C, 787,1F) và điểm sôi (907 °C) tương đối thấp.[10] Điểm sôi của nó là một trong số những điểm sôi thấp nhất của các kim loại chuyển tiếp, chỉ cao hơn thủy ngân và cadmi.[10]

Một số hợp kim với kẽm như đồng thau, là hợp kim của kẽm và đồng. Các kim loại khác có thể tạo hợp kim 2 phần với kẽm như nhôm, antimon, bitmut, vàng, sắt, chì, thủy ngân, bạc, thiếc, magiê, coban, niken, telua và natri.[11] Tuy cả kẽm và zirconi không có tính sắt từ, nhưng hợp kim của chúng ZrZn

2 lại thể hiện tính chất sắt từ dưới 35 K.[6]

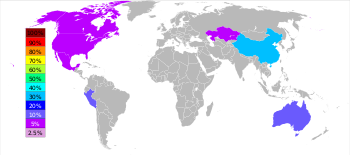

Phân bố

Kẽm chiếm khoảng 75 ppm (0,0075%) trong vỏ Trái Đất, là nguyên tố phổ biến thứ 24. Đất chứa 5–770 ppm kẽm với giá trị trung bình 64 ppm. Nước biển chỉ chứa 30 ppb kẽm và trong khí quyển chứa 0,1–4 µg/m3.[12]

Nguyên tố này thường đi cùng với các nguyên tố kim loại thông thường khác như đồng và chì ở dạng quặng.[13] Kẽm là một nguyên tố ưa tạo quặng (chalcophile), nghĩa là nguyên tố có ái lực thấp với ôxy và thường liên kết với lưu huỳnh để tạo ra các sulfua. Các nguyên tố ưa tạo quặng hình thành ở dạng lớp vỏ hóa cứng trong các điều kiện khử của khí quyển Trái Đất.[14] Sphalerit là một dạng kẽm sulfua, và là loại quặng chứa nhiều kẽm nhất với hàm lượng kẽm lên đến 60–62%.[13]

Các loại quặng khác có thể thu hồi được kẽm như smithsonit (kẽm cacbonat), hemimorphit (kẽm silicat), wurtzit (loại kẽm sulfua khác), và đôi khi là hydrozincit (kẽm cacbonat).[15] Ngoại trừ wurtzit, tất cả các khoáng trên được hình thành từ các quá trình phong hóa kẽm sulfua nguyên sinh.[14]

Tổng tài nguyên kẽm trên thế giới đã được xác nhận vào khoảng 1,9 tỉ tấn.[16] Các mỏ kẽm lớn phân bố ở Úc và Mỹ, và trữ lượng kẽm lớn nhất ở Iran.[14][17][18] Với tốc độ tiêu thụ như hiện nay thì nguồn tài nguyên này ước tính sẽ cạn kiệt vào khoảng năm từ 2027 đến 2055.[19][20] Khoảng 346 triệu tấn kẽm đã được sản xuất trong suốt chiều dài lịch sử cho đến năm 2002, và theo một ước lượng cho thấy khoảng 109 triệu tấn tồn tại ở các dạng đang sử dụng.[21]

Đồng vị

Kẽm trong tự nhiên là hỗn hợp của 5 đồng vị ổn định 64Zn, 66Zn, 67Zn, 68Zn và 70Zn, trong đó đồng vị 64 là phổ biến nhất (48,6% trong tự nhiên)[22] với chu kỳ bán rã 43×1018 năm,[23] do đó tính phóng xạ của nó có thể bỏ qua.[24] Tương tự, 70

30Zn

(0,6%), có chu kỳ bán rã 13×1016 năm thường không được xem là có tính phóng xạ. Các đồng vị khác là 66

Zn (28%), 67

Zn (4%) và 68

Zn (19%).

Một số đồng vị phóng xạ đã được nhận dạng. 65

Zn có chu kỳ bán rã 243,66 ngày, là đồng vị tồn tại lâu nhất, theo sau là 72

Zn có chu kỳ bán rã 46,5 giờ.[22] Kẽm có 10 đồng phân hạt nhân. 69mZn có chu kỳ bán rã 13,76 giờ.[22] (tham số mũ m chỉ đồng vị giả ổn định). Các hạt nhân của đồng vị giả ổn định ở trong trạng thái kích thích và sẽ trở về trạng thái bình thường khi phát ra photon ở dạng tia gamma. 61

Zn có 3 trạng thái kích thích và 73

Zn có 2 trạng thái.[25] Mỗi đồng vị 65

Zn, 71

Zn, 77

Zn và 78

Zn chỉ có một trạng thái kích thích.[22]

Cơ chế phân rã phổ biến của đồng vị phóng xạ kẽm có số khối nhỏ hơn 66 là bắt electron, sản phẩm tạo thành là một đồng vị của đồng.[22]

- n

30Zn

+ e⁻

→ n

29Cu

Cơ chế phân rã phổ biến của đồng vị phóng xạ kẽm có số khối lớn hơn 66 là phân rã beta (β–), sản phẩm tạo ra là đồng vị của gali.[22]

Hợp chất và tính chất hóa học

Khả năng phản ứng

Kẽm có cấu hình electron là [Ar]3d104s2 và là nguyên tố thuộc nhóm 12 trong bảng tuần hoàn. Nó là kim loại có độ hoạt động trung bình và là chất ôxi hóa mạnh.[26] Bề mặt của kim loại kẽm tinh khiết xỉn nhanh, thậm chí hình thành một lớp thụ động bảo vệ là kẽm cacbonat, Zn

5(OH)

6(CO3)

2, khi phản ứng với cacbon điôxít trong khí quyển.[27] Lớp này giúp chống lại quá trình phản ứng tiếp theo với nước và không khí.

Kẽm cháy trong không khí cho ngọn lửa màu xanh lục tạo ra khói kẽm ôxít.[28] Kẽm dễ dàng phản ứng với các axít, kiềm và các phi kim khác.[29] Kẽm cực kỳ tinh khiết chỉ phản ứng một cách chậm chạp với các axít ở nhiệt độ phòng.[28] Các axít mạnh như axít clohydric hay axít sulfuric có thể hòa tan lớp vảo vệ bên ngoài và sau đó kẽm phản ứng với nước giải phóng khí hydro.[28]

Tính chất hóa học của kẽm đặc trưng bởi trạng thái ôxi hóa +2. Khi các hợp chất ở trạng thái này được hình thành thì các electron lớp s bị mất đi, và ion kẽm có cấu hình electron [Ar]3d10.[30] Quá trình này cho phép tạo 4 liên kết bằng cách tiếp nhận thêm 4 cặp electron theo quy tắc bộ tám. Dạng cấu tạo hóa học lập thể là tứ diện và các liên kết có thể được miêu tả như sự tạo thành của các orbitan lai ghép sp3 của ion kẽm.[31] Trong dung dịch, nó tạo phức phổ biến dạng bát diện là [Zn(H

2O)6]2+

.[32] Sự bay hơi của kẽm khi kết hợp với kẽm clorua ở nhiệt độ trên 285 °C chỉ ra sự hình thành Zn

2Cl

2, một hợp chất kẽm có trạng thái ôxi hóa +1.[28] Không có hợp chất kẽm nào mà kẽm có trạng thái ôxi hóa khác +1 hoặc +2.[33] Các tính toán chỉ ra rằng hợp chất kẽm có trạng thái ôxi hóa +4 không thể tồn tại.[34]

Tính chất hóa học của kẽm tương tự tính chất của các kim loại chuyển tiếp nằm ở vị trí cuối cùng của hàng đầu tiên như niken và đồng, mặc dù nó có lớp d được lấp đầy electron, do đó các hợp chất của nó là nghịch từ và hầu như không màu.[35] Bán kính ion của kẽm và magiê gần như bằng nhau. Do đó một số muối của chúng có cùng cấu trúc tinh thể[36] và trong một số trường hợp khi bán kính ion là yếu tố quyết định thì tính chất hóa học của kẽm và magiê là rất giống nhau.[28] còn nếu không thì chúng có rất ít nét tương đồng. Kẽm có khuynh hướng tạo thành các liên kết cộng hóa trị với cấp độ cao hơn và nó tạo thành các phức bền hơn với các chất cho N- và S.[35] Các phức của kẽm hầu hết là có phối vị 4 hoặc 6, tuy nhiên phức phối vị 5 cũng có.[28]

Hợp chất

Hợp chất hai nguyên tố của kẽm được tạo ra với hầu hết á kim và tất cả các phi kim trừ khí hiếm. ZnO là chất bột màu trắng và hầu như không tan trong các dung dịch trung tính, vì là một chất trung tính nó tan trong cả dung dịch axit và bazơ.[28] Các chalcogenua khác (ZnS, ZnSe, và ZnTe) có nhiều ứng dụng khác nhau trong điện tử và quang học.[37] Pnictogenua (Zn

3N

2, Zn

3P

2, Zn

3As

2 và Zn

3Sb

2),[38][39] peroxit (ZnO

2), hydrua (ZnH

2), và cacbua (ZnC

2) cũng tồn tại.[40] Trong số 4 halua, ZnF

2 có đặc trưng ion nhiều nhất, trong khi các hợp chất halua khác (ZnCl

2, ZnBr

2, và ZnI

2) có điểm nóng chảy tương đối thấp và được xem là có nhiều đặc trưng cộng hóa trị hơn.[41]

Trong các dung dịch bazơ yếu chứa các ion Zn2+

, hydroxit Zn(OH)

2 tạo thành ở dạng kết tủa màu trắng. Trong các dung dịch kiềm mạnh hơn, hydroxit này bị hòa tan và tạo zincat ([Zn(OH)4]2−

).[28] Nitrat Zn(NO3)

2, clorat Zn(ClO3)

2, sulfat ZnSO

4, photphat Zn

3(PO4)

2, molybdat ZnMoO

4, cyanua Zn(CN)

2, asenit Zn(AsO2)

2, asenat Zn(AsO4)

2·8H

2O và cromat ZnCrO

4 (một trong những hợp chất kẽm có màu) là một vài ví dụ về các hợp chất vô cơ phổ biến của kẽm.[42][43] Một trong những ví dụ đơn giản nhất về hợp chất hữu cơ của kẽm là acetat (Zn(O

2CCH3)

2).

Các hợp chất hữu cơ của kẽm là dạng hợp chất mà trong đó có các liên kết cộng hóa trị kẽm-cacbon. Diethyl kẽm ((C

2H5)

2Zn) là một thuốc thử trong hóa tổng hợp. Nó được công bố đầu tiên năm 1848 từ phản ứng của kẽm và ethyl iodua, và là hợp chất đầu tiên chứa liên kết sigma kim loại-cacbon.[44] Decamethyldizincocen chứa một liên kết mạnh kẽm-kẽm ở nhiệt độ phòng.[45]

Ứng dụng

Kẽm là kim loại được sử dụng phổ biến hàng thứ tư sau sắt, nhôm, đồng tính theo lượng sản xuất hàng năm.

Chống ăn mòn và pin

Kim loại kẽm chủ yếu được dùng làm chất chống ăn mòn,[46] ở dạng mạ. Năm 2009 ở Hoa Kỳ, 55% tương đương 893 tấn kẽm kim loại được dùng để mạ.[47]

Kẽm phản ứng mạnh hơn sắt hoặc thép và do đó nó sẽ dễ bị ô xy hóa cho đến khi nó bị ăn mòn hoàn toàn.[48] Một lớp tráng bề mặt ở dạng bằng ôxít và carbonat (Zn

5(OH)

6(CO

3)

2) là một chất ăn mòn từ kẽm.[49] Lớp bảo vệ này tồn tại kéo dài ngay cả sau khi lớp kẽm bị trầy xướt, nhưng nó sẽ giảm theo thời gian khi lớp ăn mòn kẽm bị tróc đi.[49] Kẽm được phủ lên theo phương pháp hóa điện bằng cách phun hoặc mạ nhúng nóng.[12] Mạ được sử dụng trên rào kẽm gai, rào bảo vệ, cầu treo, mái kim loại, thiết bị trao đổi nhiệt, và bộ phận của ô tô.[12]

Độ hoạt động tương đối của kẽm và khả năng của nó bị ôxy hóa làm nó có hiệu quả trong việc hi sinh anot để bảo vệ ăn mòn catot. Ví dụ, bảo vệ catot của một đường ống được chôn dưới đất có thể đạt hiệu quả bằng cách kết nối các anot được làm bằng kẽm với các ống này.[49] Kẽm có vai trò như một anot (âm) bằng các ăn mòn một cách chậm chạp khi dòng điện chạy qua nó đến ống dẫn bằng thép.[49][note 1] Kẽm cũng được sử dụng trong việt bảo vệ các kim loại được dùng làm catot khi chúng bị ăn mòn khi tiếp xúc với nước biển.[50] Một đĩa kẽm được gắn với một bánh lái bằng sắt của tàu sẽ làm chậm tốc độ ăn mòn so với không gắn tấm kẽm này.[48] Các ứng dụng tương tự như gắn kẽm vào chân vịt hoặc lớp kim loại bảo vệ lườn tàu.

Với một thế điện cực chuẩn (SEP) 0,76 vôn, kẽm được sử dụng làm vật liệu anot cho pin. Bột kẽm được sử dụng theo cách này trong các loại pin kiềm và các tấm kẽm kim loại tạo thành vỏ bọc và cũng là anot trong pin kẽm-carbon.[51][52] Kẽm được sử dụng làm anot hoặc nhiên liệu cho tế bào nhiêu liệu kẽm/pin kẽm-không khí.[53][54][55]

Bài viết này là công việc biên dịch đang được tiến hành từ bài viết [[:FromLanguage:|]] từ một ngôn ngữ khác sang tiếng Việt. Bạn có thể giúp Wikipedia bằng cách hỗ trợ dịch và trau chuốt lối hành văn tiếng Việt theo cẩm nang của Wikipedia. |

Hợp kim

A widely used alloy which contains zinc is brass, in which copper is alloyed with anywhere from 3% to 45% zinc, depending upon the type of brass.[49] Brass is generally more ductile and stronger than copper and has superior corrosion resistance.[49] These properties make it useful in communication equipment, hardware, musical instruments, and water valves.[49]

Other widely used alloys that contain zinc include nickel silver, typewriter metal, soft and aluminium solder, and commercial bronze.[6] Zinc is also used in contemporary pipe organs as a substitute for the traditional lead/tin alloy in pipes.[56] Alloys of 85–88% zinc, 4–10% copper, and 2–8% aluminium find limited use in certain types of machine bearings. Zinc is the primary metal used in making American one cent coins since 1982.[57] The zinc core is coated with a thin layer of copper to give the impression of a copper coin. In 1994, 33.200 tấn (36.600 tấn Mỹ) of zinc were used to produce 13.6 billion pennies in the United States.[58]

Alloys of primarily zinc with small amounts of copper, aluminium, and magnesium are useful in die casting as well as spin casting, especially in the automotive, electrical, and hardware industries.[6] These alloys are marketed under the name Zamak.[59] An example of this is zinc aluminium. The low melting point together with the low viscosity of the alloy makes the production of small and intricate shapes possible. The low working temperature leads to rapid cooling of the cast products and therefore fast assembly is possible.[6][60] Another alloy, marketed under the brand name Prestal, contains 78% zinc and 22% aluminium and is reported to be nearly as strong as steel but as malleable as plastic.[6][61] This superplasticity of the alloy allows it to be molded using die casts made of ceramics and cement.[6]

Similar alloys with the addition of a small amount of lead can be cold-rolled into sheets. An alloy of 96% zinc and 4% aluminium is used to make stamping dies for low production run applications for which ferrous metal dies would be too expensive.[62] In building facades, roofs or other applications in which zinc is used as sheet metal and for methods such as deep drawing, roll forming or bending, zinc alloys with titanium and copper are used.[63] Unalloyed zinc is too brittle for these kinds of manufacturing processes.[63]

As a dense, inexpensive, easily worked material, zinc is used as a lead replacement. In the wake of lead concerns, zinc appears in weights for various applications ranging from fishing[64] to tire balances and flywheels.[65]

Cadmium zinc telluride (CZT) is a semiconductive alloy that can be divided into an array of small sensing devices.[66] These devices are similar to an integrated circuit and can detect the energy of incoming gamma ray photons.[66] When placed behind an absorbing mask, the CZT sensor array can also be used to determine the direction of the rays.[66]

Các ứng dụng công nghiệp khác

Roughly one quarter of all zinc output in the United States (2009), is consumed in the form of zinc compounds;[47] a variety of which are used industrially. Zinc oxide is widely used as a white pigment in paints, and as a catalyst in the manufacture of rubber. It is also used as a heat disperser for the rubber and acts to protect its polymers from ultraviolet radiation (the same UV protection is conferred to plastics containing zinc oxide).[12] The semiconductor properties of zinc oxide make it useful in varistors and photocopying products.[67] The zinc zinc-oxide cycle is a two step thermochemical process based on zinc and zinc oxide for hydrogen production.[68]

Zinc chloride is often added to lumber as a fire retardant[69] and can be used as a wood preservative.[70] It is also used to make other chemicals.[69] Zinc methyl (Zn(CH3)

2) is used in a number of organic syntheses.[71] Zinc sulfide (ZnS) is used in luminescent pigments such as on the hands of clocks, X-ray and television screens, and luminous paints.[72] Crystals of ZnS are used in lasers that operate in the mid-infrared part of the spectrum.[73] Zinc sulfate is a chemical in dyes and pigments.[69] Zinc pyrithione is used in antifouling paints.[74]

Zinc powder is sometimes used as a propellant in model rockets.[75] When a compressed mixture of 70% zinc and 30% sulfur powder is ignited there is a violent chemical reaction.[75] This produces zinc sulfide, together with large amounts of hot gas, heat, and light.[75] Zinc sheet metal is used to make zinc bars.[76]

64

Zn, the most abundant isotope of zinc, is very susceptible to neutron activation, being transmuted into the highly radioactive 65

Zn, which has a half-life of 244 days and produces intense gamma radiation. Because of this, Zinc Oxide used in nuclear reactors as an anti-corrosion agent is depleted of 64

Zn before use, this is called depleted zinc oxide. For the same reason, zinc has been proposed as a salting material for nuclear weapons (cobalt is another, better-known salting material).[77] A jacket of isotopically enriched 64

Zn would be irradiated by the intense high-energy neutron flux from an exploding thermonuclear weapon, forming a large amount of 65

Zn significantly increasing the radioactivity of the weapon's fallout.[77] Such a weapon is not known to have ever been built, tested, or used.[77] 65

Zn is also used as a tracer to study how alloys that contain zinc wear out, or the path and the role of zinc in organisms.[78]

Zinc dithiocarbamate complexes are used as agricultural fungicides; these include Zineb, Metiram, Propineb and Ziram.[79] Zinc naphthenate is used as wood preservative.[80] Zinc, in the form of ZDDP, is also used as an anti-wear additive for metal parts in engine oil.[81]

Bổ sung trong khẩu phần ăn

Zinc is included in most single tablet over-the-counter daily vitamin and mineral supplements.[82] Preparations include zinc oxide, zinc acetate, and zinc gluconate.[82] It is believed to possess antioxidant properties, which may protect against accelerated aging of the skin and muscles of the body; studies differ as to its effectiveness.[83] Zinc also helps speed up the healing process after an injury.[83] It is also beneficial to the body's immune system. Indeed, zinc deficiency may have effects on virtually all parts of the human immune system.[84] The efficacy of zinc compounds when used to reduce the duration or severity of cold symptoms is controversial.[85] A 2011 systematic review concludes that supplementation yields a mild decrease in duration and severity of cold symptoms.[86]

Zinc serves as a simple, inexpensive, and critical tool for treating diarrheal episodes among children in the developing world. Zinc becomes depleted in the body during diarrhea, but recent studies suggest that replenishing zinc with a 10- to 14-day course of treatment can reduce the duration and severity of diarrheal episodes and may also prevent future episodes for up to three months.[87]

The Age-Related Eye Disease Study determined that zinc can be part of an effective treatment for age-related macular degeneration.[88] Zinc supplementation is an effective treatment for acrodermatitis enteropathica, a genetic disorder affecting zinc absorption that was previously fatal to babies born with it.[89]

Gastroenteritis is strongly attenuated by ingestion of zinc, and this effect could be due to direct antimicrobial action of the zinc ions in the gastrointestinal tract, or to the absorption of the zinc and re-release from immune cells (all granulocytes secrete zinc), or both.[90][91][note 2] In 2011, researchers at John Jay College of Criminal Justice reported that dietary zinc supplements can mask the presence of drugs in urine. Similar claims have been made in web forums on that topic.[92]

Although not yet tested as a therapy in humans, a growing body of evidence indicates that zinc may preferentially kill prostate cancer cells. Because zinc naturally homes to the prostate and because the prostate is accessible with relatively non-invasive procedures, its potential as a chemotherapeutic agent in this type of cancer has shown promise.[93] However, other studies have demonstrated that chronic use of zinc supplements in excess of the recommended dosage may actually increase the chance of developing prostate cancer, also likely due to the natural buildup of this heavy metal in the prostate.[94]

Dùng làm thuốc ngoài da

Topical administration of zinc preparations include ones used on the skin, often in the form of zinc oxide. Zinc preparations can protect against sunburn in the summer and windburn in the winter.[89] Applied thinly to a baby's diaper area (perineum) with each diaper change, it can protect against diaper rash.[89]

Zinc lactate is used in toothpaste to prevent halitosis.[95] Zinc pyrithione is widely applied in shampoos because of its anti-dandruff function.[96] Zinc ions are effective antimicrobial agents even at low concentrations.[97]

Hóa hữu cơ

There are many important organozinc compounds. Organozinc chemistry is the science of organozinc compounds describing their physical properties, synthesis and reactions.[98][99][100][101] Among important applications is the Frankland-Duppa Reaction in which an oxalate ester(ROCOCOOR) reacts with an alkyl halide R'X, zinc and hydrochloric acid to the α-hydroxycarboxylic esters RR'COHCOOR,[102] the Reformatskii reaction which converts α-halo-esters and aldehydes to β-hydroxy-esters, the Simmons–Smith reaction in which the carbenoid (iodomethyl)zinc iodide reacts with alkene(or alkyne) and converts them to cyclopropane, the Addition reaction of organozinc compounds to carbonyl compounds. The Barbier reaction (1899) which is the zinc equivalent of the magnesium Grignard reaction and is better of the two. In presence of just about any water the formation of the organomagnesium halide will fail whereas the Barbier reaction can even take place in water. On the downside organozincs are much less nucleophilic than Grignards, are expensive and difficult to handle. Commercially available diorganozinc compounds are dimethylzinc, diethylzinc and diphenylzinc. In one study[103][104] the active organozinc compound is obtained from much cheaper organobromine precursors:

The Negishi coupling is also an important reaction for the formation of new carbon carbon bonds between unsaturated carbon atoms in alkenes, arenes and alkynes. The catalysts are nickel and palladium. A key step in the catalytic cycle is a transmetalation in which a zinc halide exchanges its organic substituent for another halogen with the palladium (nickel) metal center. The Fukuyama coupling is another coupling reaction but this one with a thioester as reactant forming a ketone.

Hợp chất

Ô xít kẽm có lẽ là hợp chất được sử dụng rộng rãi nhất của kẽm, do nó tạo ra nền trắng tốt cho chất liệu màu trắng trong sản xuất sơn. Nó cũng có ứng dụng trong công nghiệp cao su, và nó được mua bán như là chất chống nắng mờ. Các loại hợp chất khác cũng có ứng dụng trong công nghiệp, chẳng hạn như clorua kẽm (chất khử mùi), sulfua kẽm (lân quang), methyl kẽm trong các phòng thí nghiệm về chất hữu cơ. Khoảng một phần tư sản lượng kẽm sản xuất hàng năm được tiêu thụ dưới dạng các hợp chất của nó.

- Ôxít kẽm được sử dụng như chất liệu có màu trắng trong màu nước và sơn cũng như chất hoạt hóa trong công nghiệp ô tô. Sử dụng trong thuốc mỡ, nó có khả năng chống cháy nắng cho các khu vực da trần. Sử dụng như lớp bột mỏng trong các khu vực ẩm ướt của cơ thể (bộ phận sinh dục) của trẻ em để chống hăm.

- Clorua kẽm được sử dụng làm chất khử mùi và bảo quản gỗ.

- Sulfua kẽm được sử dụng làm chất lân quang, được sử dụng để phủ lên kim đồng hồ hay các đồ vật khác cần phát sáng trong bóng tối.

- Methyl kẽm (Zn(CH3)2) được sử dụng trong một số phản ứng tổng hợp chất hữu cơ.

- Stearat kẽm được sử dụng làm chất độn trong sản xuất chất dẻo (plastic) từ dầu mỏ.

- Các loại nước thơm sản xuất từ calamin, là hỗn hợp của(hydroxy-)cacbonat kẽm và silicat, được sử dụng để chống phỏng da.

- Trong thực đơn hàng ngày, kẽm có trong thành phần của các loại khoáng chất và vitamin. Người ta cho rằng kẽm có thuộc tính chống ôxi hóa, do vậy nó được sử dụng như là nguyên tố vi lượng để chống sự chết yểu của da và cơ trong cơ thể (lão hóa). Trong các biệt dược chứa một lượng lớn kẽm, người ta cho rằng nó có tác dụng nhanh làm lành vết thương.

- Gluconat glycin kẽm trong các viên nang hình thoi có tác dụng chống cảm.

Lịch sử

Thời kỳ cổ đại

Các mẫu vật riêng biệt sử dụng kẽm không nguyên chất trong thời kỳ cổ đại đã được phát hiện. Một bức tượng nhỏ có thể từ thời tiền sử chứa 87,5% kẽm được tìm thấy ở di chỉ khảo cổ Dacia ở Transylvania (Romania ngày nay).[105] Các đồ trang trí bằng hợp kim chứa 80–90% kẽm với chì, sắt, antimon và các kim loại khác cấu thành phần còn lại, đã được phát hiện có độ tuổi là 2.500 năm.[13] Bảng kẽm Bern là một tấm thẻ tạ ơn có niên đại tới thời kỳ Gaul La Mã được làm bằng hợp kim bao gồm phần lớn là kẽm.[106] Một số văn bản cổ đại dường như cũng đề cập đến kẽm. Sử gia Hy Lạp Strabo, trong một đoạn văn lấy từ nhà văn trước đó trong thế kỷ 4 TCN, đề cập tới "những giọt bạc giả", được trộn lẫn với đồng để làm đồng thau. Điều này có thể đề cập đến một lượng nhỏ kẽm là phụ phẩm của quá trình nung chảy quặng sulfua.[107] Charaka Samhita, cho là đã được viết vào 500 TCN hay trước đó nữa, đề cập đến một kim loại mà khi bị ôxi hóa, tạo ra pushpanjan, sản phẩm được cho là kẽm ôxít.[108]

Các loại quặng kẽm đã được sử dụng để làm hợp kim đồng-kẽm là đồng thau vài thế kỷ trước khi phát hiện ra kẽm ở dạng nguyên tố riêng biệt. Đồng thau Palestin có từ thế kỷ 14 TCN đến thế kỷ 10 TCN chứa 23% kẽm.[109]

Việc sản xuất đồ đồng thau đã được người La Mã biết đến vào khoảng năm 30 TCN,[89] họ sử dụng công nghệ nấu calamin (kẽm silicat hay cacbonat) với than củi và đồng trong các nồi nấu.[89] Lượng ôxít kẽm giảm xuống và kẽm tự do bị đồng giữ lại, tạo ra hợp kim là đồng thau. Đồng thau sau đó được đúc hay rèn thành các chủng loại đồ vật và vũ khí.[110] Một số tiền xu từ người La Mã trong thời đại Công giáo được làm từ loại vật liệu có thể là đồng thau calamin.[111] Ở phương Tây, kẽm lẫn tạp chất từ thời cổ đại tồn tại ở dạng tàn dư trong lò nung chảy, nhưng nó thường bị bỏ đi vì người ta nghĩ nó không có giá trị.[112]

Các mỏ kẽm ở Zawar, gần Udaipur, Ấn Độ đã từng hoạt động từ thời đại Maurya vào cuối thiên niên kỷ 1 TCN. Việc nấu chảy và phân lập kẽm nguyên chất đã được những người Ấn Độ thực hiện sớm nhất vào thế kỷ 12.[113][114] Một ước tính cho thấy rằng khu vực này đã sản xuất ra khoảng vài triệu tấn kẽm kim loại và kẽm ôxít từ thế kỷ 12 đến thế kỷ 16.[15] Một ước tính khác đưa ra con số sản lượng là 60.000 tấn kẽm kim loại trong giai đoạn này.[113] Rasaratna Samuccaya, được viết vào khoảng thế kỷ 14, đề cập đến 2 loại quặng chứa kẽm; một loại được sử dụng để tách kim loại và loại khác được dùng cho y học.[114]

Các nghiên cứu trước đây và tên gọi

Kẽm đã từng được công nhận là một kim loại có tên gọi ban đầu là Fasada theo như y học Lexicon được cho là của vua Hindu Madanapala và được viết vào khoảng năm 1374.[115] Nung chảy và tách kẽm nguyên chất bằng cách khử calamin với len và các chất hữu cơ khác đã được tiến hành vào thế kỷ 13 ở Ấn Độ.[6][116] Người Trung Quốc cho tới thế kỷ 17 vẫn chưa học được kỹ thuật này.[116]

Các nhà giả kim thuật đã đốt kẽm kim loại trong không khí và thu được kẽm ôxít trong một lò ngưng tụ. Một số nhà giả kim thuật gọi loại kẽm ôxít này là lana philosophica, tiếng Latin có nghĩa là "len của các nhà triết học", do nó được thu hồi từ búi len trong khi những người khác nghĩ nó giống như tuyết trắng và đặt tên nó là nix album.[117]

Tên gọi của kẽm ở phương Tây có thể được ghi nhận đầu tiên bởi nhà giả kim Đức gốc Thụy Sĩ Paracelsus, ông đã gọi tên kim loại này là "zincum" hay "zinken" trong quyển sách của mình là Liber Mineralium II được viết vào thế kỷ 16.[116][118] Từ này có thể bắt nguồn từ tiếng Đức [zinke] lỗi: {{lang}}: văn bản có thẻ đánh dấu in xiên (trợ giúp), và có thể có nghĩa là "giống như răng, nhọn hoặc lởm chởm" (các tinh thể kẽm kim loại có hình dạng giống như những chiếc kim).[119] Zink cũng có thể ám chỉ "giống như tin (thiếc)" do mối quan hệ của nó (trong tiếng Đức zinn nghĩa là thiếc).[120] Một khả năng khác có thể là từ đó xuất phát từ tiếng Ba Tư سنگ seng nghĩa là đá.[121] Kim loại cũng có thể gọi là thiếc Ấn Độ, tutanego, calamin, và spinter.[13]

Nhà luyện kim người Đức Andreas Libavius đã nhận được một lượng vật liệu mà ông gọi là "calay" của Malabar từ một tàu chở hàng bắt được ở Bồ Đào Nha năm 1596.[122] Libavius đã miêu tả các thuộc tính của mẫu vật có thể là kẽm này. Kẽm thường được nhập khẩu đến châu Âu từ các nước phương Đông trong thế kỷ 17 và đầu thế kỷ 18,[116] nhưng rất đắt giá vào lúc đó.[note 3]

Tách kẽm nguyên chất

Việc tách kim loại kẽm ở phương Tây có thể đã đạt được những thành tựu một cách độc lập từ một số người. Universal Dictionary (Từ điển tổng hợp) của Postlewayt, một nguồn cung cấp thông tin kỹ thuật ở châu Âu, đã không đề cập đến kẽm trước năm 1751, nhưng nguyên tố này đã được nghiên cứu từ trước đó.[114][123]

Nhà luyện kim người Flanders là P.M. de Respour đã công bố rằng ông đã tách được kẽm kim loại từ kẽm ôxít năm 1668.[15] Sau đó, Étienne François Geoffroy đã miêu tả cách thức mà kẽm ôxít cô đặc lại thành các tinh thể màu vàng trên các thanh sắt được đặt bên trên các quặng kẽm đang nóng chảy.[15] Ở Anh, John Lane được cho là đã tiến hành các thí nghiệm để nung chảy kẽm, có thể ở Landore, trước khi ông phá sản năm 1726.[124]

Năm 1738, William Champion được cấp bằng sáng chế ở Đại Anh cho quá trình tách kẽm từ calamin trong một lò luyện theo kiểu bình cổ cong thẳng đứng.[125] Công nghệ của ông một phần nào đó giống với cách được sử dụng trong các mỏ kẽm ở Zawar thuộc Rajasthan nhưng không có bằng chứng nào cho thấy ông đã đến vùng phương đông.[126] Phương pháp của Champion được sử dụng suốt năm 1851.[116]

Nhà hóa học người Đức Andreas Marggraf được xem là có công trong việc phát hiện ra kẽm kim loại nguyên chất mặc dù nhà hóa học Thụy Điển là Anton von Swab đã chưng cất kẽm từ calamin 4 năm trước đó.[116] Trong thí nghiệm năm 1746 của ông, Marggraf đã nung hỗm hợp calamin và than củi trong một buồng kín không có đồng để lấy kim loại.[112] Quy trình này được ứng dụng ở quy mô thương mại từ năm 1752.[127]

Các công trình sau này

Một người anh em của William Champion là John đã nhận được bằng sáng chế năm 1758 về việc nung kẽm sulfua thành một ôxít có thể sử dụng trong quy trình chưng cất bằng lò cổ cong.[13] Trước đó chỉ có calamin mới có thể được sử dụng để sản xuất kẽm. Năm 1798, Johann Christian Ruberg cải tiến quá trình nung chảy bằng cách xây dựng một lò nung chưng cất nằm ngang.[128] Jean-Jacques Daniel Dony đã xây dựng một lò nung chảy nằm ngang theo một kiểu khác ở Bỉ, lò nung này có thể xử lý nhiều kẽm hơn.[116] Bác sĩ người Ý Luigi Galvani khám phá ra vào năm 1780 rằng việc kết nối tủy sống của một con ếch vừa mới mổ với một sợi sắt có gắn một cái mốc bằng đồng thau sẽ làm cho chân ếch co giật.[129] Ông ta đã nghĩ không chính xác rằng ông đã phát hiện một khả năng của nơ ron và cơ để tạo ra điện và gọi đó là hiệu ứng "điện động vật".[130] Tế bào mạ và quá trình mạ đều được đặt tên theo Luigi Galvani và những phát hiện này đã mở đường cho pin điện, mạ điện và chống ăn mòn điện.[130]

Bạn của Galvani là Alessandro Volta đã tiếp tục nghiên cứu hiệu ứng này và đã phát minh ra pin Volta năm 1800.[129] Đơn vị cơ bản của pin Volta là các tế bào mạ điện được đơn giản hóa, chúng được làm từ một tấm đồng và một tấm kẽm được gắn kết với nhhau ở bên ngoài và ngăn cách bởi một lớp điện ly. Các tấm này được xếp thành một chuỗi để tạo ra tế bào Volta, các tế bào này tạo ra điện bằng các dòng electron chạy từ tấm kẽm qua tấm đồng và cho phép kẽm ăn mòn.[129]

Tính chất không từ tính của kẽm và không màu của nó trong dung dịch đã làm trì hoãn việc phát hiện ra những tính chất quan trọng của chíng trong sinh hóa và dinh dưỡng.[131] Nhưng điều đó đã thay đổi vào năm 1940 khi mà cacbonic anhydrase, một loại enzym đẩy cacbon điôxít ra khỏi máu, đã cho thấy kẽm có vai trò quan trọng trong nó.[131] Enzym tiêu hóa carboxypeptidase là enzym chứa kẽm thứ hai được phát hiện năm 1955.[131]

Sản xuất

Khai thác mỏ và xử lý

| Hạng | Quốc gia | Tấn |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3,500,000 | |

| 2 | 1,520,000 | |

| 3 | 1,450,000 | |

| 4 | 750,000 | |

| 5 | 720,000 | |

| 6 | 670,000 |

Kẽm là kim loại được sử dụng phổ biến thứ 4 sau sắt, nhôm và đồng với sản lượng hàng năm khoảng 12 triệu tấn.[16] Nhà sản xuất kẽm lớn nhất thế giới là Nyrstar, công ty sáp nhập từ OZ Minerals của Úc và Umicore của Bỉ.[133] Khoảng 70% lượng kẽm trên thế giới có nguồn gốc từ khai thác mỏ, lượng còn lại từ hoạt động tái sử dụng.[134] Kẽm tinh khiết cấp thương mại có tên gọi trong giao dịch tiếng Anh là Special High Grade (SHG) có độ tinh khiết 99,995%.[135]