Thành viên:Hồ Đức Hải/nháp 1

| Một biên tập viên đang sửa phần lớn trang thành viên này trong một thời gian ngắn. Để tránh mâu thuẫn sửa đổi, vui lòng không chỉnh sửa trang khi còn xuất hiện thông báo này. Người đã thêm thông báo này sẽ được hiển thị trong lịch sử trang này. Nếu như trang này chưa được sửa đổi gì trong vài giờ, vui lòng gỡ bỏ bản mẫu. Nếu bạn là người thêm bản mẫu này, hãy nhớ xoá hoặc thay bản mẫu này bằng bản mẫu {{Đang viết}} giữa các phiên sửa đổi. Trang này được sửa đổi lần cuối vào lúc 17:27, 21 tháng 6, 2024 (UTC) (12 giây trước) — Xem khác biệt hoặc trang này. |

| Hồ Đức Hải/nháp 1 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Phân loại khoa học | |

| Giới: | Plantae |

| nhánh: | Tracheophyta |

| nhánh: | Angiospermae |

| nhánh: | Monocots |

| Bộ: | Alismatales |

| Họ: | Araceae |

| Chi: | Colocasia |

| Loài: | C. esculenta

|

| Danh pháp hai phần | |

| Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott | |

| Các đồng nghĩa[1][2][3] | |

| |

Khoai môn[4][5][6] (/ˈtɑːroʊ,

Tên thường gọi[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Thuật ngữ khoai môn trong tiếng Anh taro được mượn từ tiếng Māori khi thuyền trưởng Cook lần đầu tiên quan sát các đồn điền Colocasia ở New Zealand vào năm 1769. Hình thái taro hay talo phổ biến trong các ngôn ngữ Polynesia:[7] taro trong tiếng Tahiti; talo bằng tiếng Samoa và Tonga; kalo trong tiếng Hawaii ; taʻo ở tiếng Marquesas. Tất cả hình thái này đều bắt nguồn từ *talo trong ngữ hệ nguyên thủy của Polynesia,[7] mà bản thân nó có nguồn gốc từ *talos trong ngữ hệ nguyên thủy châu Đại Dương (cf. dalo trong tiếng Fiji) và *tales trong ngữ hệ nguyên thủy của Nam Đảo (cf. tales trong tiếng Java).[8] Tuy nhiên, sự bất thường trong tương ứng âm thanh giữa các dạng cùng nguồn gốc trong tiếng Nam Đảo gợi ý rằng thuật ngữ này có thể được mượn và lan truyền từ một ngôn ngữ Nam Á, có lẽ ở Borneo (vd: ngữ hệ nguyên thủy Môn Khmer * t 2 rawʔ, Khasi shriew, Khmu sroʔ).[9]

Trong ngôn ngữ Odia (được sử dụng rộng rãi ở vùng Odisha[10] của Ấn Độ), chúng được gọi là sāru (ସାରୁ).[10]

Ở Síp, khoai môn đã được sử dụng từ thời đế quốc La Mã. Ngày nay chúng được gọi là kolokasi (Kολοκάσι). Chúng thường được chiên hoặc nấu với ngô, thịt lợn hoặc thịt gà trong nước sốt cà chua trong nồi đất. "Baby" kolokasi được gọi là "poulles": sau khi chiên khô, thêm rượu vang đỏ và hạt rau mùi vào, sau đó dùng kèm với chanh tươi vắt. Gần đây, một số nhà hàng đã bắt đầu phục vụ những lát kolokasi chiên giòn mỏng, gọi chúng là "kolokasi lát mỏng".

| Name | Language |

|---|---|

| gabi | Tagalog |

| natong/apay | Bikolano[11] |

| ede | Igbo |

| jimbi | Swahili |

| kókò/lámbó | Yoruba |

| kacu (কচু) | Assamese |

| kacu (কচু) | Bengali[12] |

| kacu (কচু) | Kamtapuri/Rajbongshi/Rangpuri |

| kolokasi (Kολοκάσι) | Cypriot Greek |

| kēsave (ಕೇಸವೆ) | Kannada |

| qulqas (قلقاس) | Arabic |

| kontomire | Akan |

| kiri aḷa (කිරි අළ) | Sinhala |

| arbī (अरबी) | Hindi |

| arvi (ਅਰਵੀ) | Punjabi |

| aruī (अरुई) | Bhojpuri |

| arikanchan (अरिकञ्चन) | Maithili[13] |

| aḷavī (અળવી) | Gujarati |

| āḷū (आळू) | Marathi |

| ala (އަލަ) | Dhivehi |

| aba | Ilocano |

| sāru (ସାରୁ) | Odia |

| piḍālu (पिडालु) | Nepali |

| cēmpu (சேம்பு) | Tamil |

| cēmpŭ (ചേമ്പ്) | Malayalam |

| cāma (చామ) | Telugu |

| (khoai) môn | Vietnamese |

| vēnṭī (वेंटी) | Konkani |

| yendem (ꯌꯦꯟꯗꯦꯝ) | Meitei/Manipuri |

| 芋 (yù)/芋頭 (yùtou) | Chinese |

| 芋 (ō͘/ū) or 芋仔 (ō͘-á) | Taiwanese Hokkien[14] |

| vasa | Paiwan[15] |

| tali | Amis[16][17] |

| Chinese tayer | Surinamese Dutch |

| saonjo | Malagasy |

| toran (토란) | Korean |

| tolotolo | Bukusu |

| pheuak, puak (เผือก) | Thai |

| pheuak, puak (ເຜືອກ) | Lao |

| kheu (ခုၣ်) | S'gaw Karen |

| nabbiag | Ahamb |

| pweta | Wusi |

| *b(u,i)aqa, *bweta | Proto North-Central-Vanuatu (reconstructed)[18] |

| *talo(s), *mʷapo(q), *piRaq, *bulaka, *kamʷa, *(b,p)oso | Proto Oceanic (reconstructed)[19] |

Những cái tên khác bao gồm amadumbe hoặc madumbi trong tiếng Zulu,[20] boina trong tiếng Wolaita của Ethiopia, hoặc amateke ở Kirundi và Kinyarwanda.[21] Ở Tanzania, chúng được gọi là magimbi trong tiếng Swahili. Ở Madagascar, chúng được gọi là saonjo. Chúng còn được gọi là eddo ở Liberia .

Ở Caribe và Tây Ấn, khoai môn được gọi là dasheen ở Trinidad và Tobago, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent và Grenadines[22] và Jamaica.[23]:23 Lá cây được người Indo-Trinidad và Tobago gọi là aruiya ke bhaji.[24]

Trong tiếng Bồ Đào Nha, chúng được gọi đơn giản là taro, cũng như inhame, inhame-coco, taioba, taiova, taioba-de-são-tomé hoặc matabala;[25][26] trong tiếng Tây Ban Nha, chúng được gọi là malanga.[27][28]

Từ ngữ Hy Lạp cổ κολοκάσιον (kolokasion, nghĩa đen 'rễ sen') là nguồn gốc của từ ngữ kolokasi trong tiếng Hy Lạp hiện đại (κολοκάσι), từ ngữ kolokas bằng cả tiếng Hy Lạp và tiếng Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ và qulqas (قلقاس) bằng tiếng Ả Rập. Nó được tiếng Latin mượn thành colocasia, do đó trở thành danh pháp chi Colocasia.[29][30]

Khoai môn là một trong những loài được trồng rộng rãi nhất trong nhóm thực vật lâu năm nhiệt đới, thường được gọi thông tục là "tai voi", khi được trồng làm cây cảnh.[31] Các loài thực vật khác có cùng biệt danh bao gồm một số loài ráy có liên hệ sở hữu lá lớn hình trái tim, thường nằm trong các chi như Alocasia, Caladium, Monstera, Philodendron, Syngonium, Thaumatophyllum và Xanthosoma.

Ở Philippines, toàn bộ cây thường được gọi là gabi, trong khi thân cây được gọi là taro. Khoai môn là hương vị trà sữa rất phổ biến trong nước và cũng là nguyên liệu quen thuộc trong một số món ăn mặn của Philippines như sinigang.

Mô tả[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

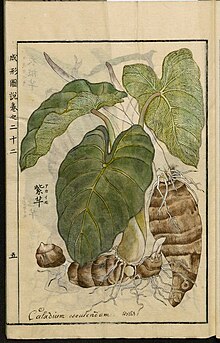

Khoai môn là thực vật nhiệt đới lâu năm, chủ yếu được trồng làm rau ăn củ để lấy thân củ có nhiều tinh bột, ăn được. Cây có thân rễ với nhiều hình dạng và kích cỡ khác nhau. Lá dài đến 40 cm × 25 cm (15,7 in × 9,8 in) và mọc ra từ thân rễ. Chúng có màu xanh đậm ở trên và màu xanh nhạt ở dưới. Chúng có hình ovan gần nhọn, hơi tròn và có hình mút nhọn ở đỉnh, với đầu của các thùy đáy tròn hoặc hơi tròn. Cuống lá cao 0,8–1,2 m (2,6–3,9 ft). Ống lá có thể dài đến 25 cm (10 in). Bông mo dài khoảng 3/5 đoạn mo, với phần đóa hoa có đường kính dài đến 8 mm (0,31 in). Cụm hoa cái nằm ở bầu nhụy màu mỡ xen lẫn với bầu khác màu trắng vô sinh. Hoa vô tính phát triển phía trên hoa cái và có thùy hình thoi hoặc không đều, có 6 hoặc 8 tế bào. Phần phụ ngắn hơn cụm hoa đực.

-

Hoa

-

Lá

-

Củ dạng thân hành

-

Củ (lát cắt ngang)

Loài tương tự[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Khoai môn có họ hàng với Xanthosoma và Caladium, những loại cây thường được trồng làm cảnh. Giống như chúng, đôi khi được gọi một cách mơ hồ là tai voi. Các giống khoai môn tương tự gồm có khoai môn khổng lồ (Alocasia macrorrhizos), khoai môn đầm lầy (Cyrtosperma merkusii) và tai voi có lá mũi tên (Xanthosoma sagittifolium).

Phân loại[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Carl Linnaeus ban đầu mô tả hai loài, Colocasia esculenta và Colocasia antiquorum, nhưng nhiều nhà thực vật học sau này xem cả hai đều là thành viên của một loài duy nhất, rất đa dạng, danh pháp chính xác là Colocasia esculenta.[32]

Từ nguyên[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Tính ngữ khoa học, esculenta, có nghĩa là "ăn được" trong tiếng Latin.

Phân bố và sinh cảnh[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Khoai môn được cho là có nguồn gốc từ Nam Ấn Độ và Đông Nam Á nhưng được du nhập rộng rãi.[33][34] Khoai được cho là có nguồn gốc từ vương quốc Indomalaya, có lẽ ở Đông Ấn Độ, Nepal và Bangladesh. Khoai lan truyền bằng con đường trồng trọt theo hướng đông vào Đông Nam Á, Đông Á và hải đảo Thái Bình Dương; theo phía tây đến Ai Cập và miền đông lưu vực Địa Trung Hải; rồi từ đó hướng về phía nam và phía tây vào Đông Phi và Tây Phi, nơi mà khoai lan truyền đến vùng Caribe và châu Mỹ.

Khoai môn có lẽ có nguồn gốc đầu tiên ở vùng đất ngập nước thấp của Malaysia, nơi chúng được gọi là taloes .

Ở Úc, C. esculenta var. aquatilis được cho là có nguồn gốc ở vùng Kimberley thuộc Tây Úc; giống esculenta phổ biến hiện đã được du nhập và được xem là một loại cỏ dại xâm lấn ở Tây Úc, Lãnh thổ Bắc Úc, Queensland và New South Wales.

Ở châu Âu, C. esculenta được trồng tại Síp và được gọi là Colocasi (Κολοκάσι trong tiếng Hy Lạp) và được chứng nhận là sản phẩm PDO. Khoai cũng sinh sống trên đảo Ikaria của Hy Lạp và được xem là nguồn thực phẩm quan trọng cho hòn đảo trong Thế chiến thứ hai.[35]

Ở Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ, C. esculenta có tên địa phương là gölevez và được trồng chủ yếu ven bờ biển Địa Trung Hải, chẳng hạn như huyện Alanya của tỉnh Antalya và huyện Anamur của tỉnh Mersin.

Ở Macaronesia, loại cây này đã được du nhập, có lẽ là kết quả của những khám phá của người Bồ Đào Nha và thường được dùng trong chế độ ăn của người Macaronesia như một nguồn carbohydrat quan trọng.

Ở miền đông nam Hoa Kỳ, loài cây này được công nhận là loài xâm lấn.[36][37][38][39][40] Nhiều quần thể thường tìm được mọc gần các mương thoát nước và bayou ở Houston, Texas.

Trồng trọt[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Lịch sử[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Khoai môn là một trong những loại cây trồng cổ xưa nhất.[41][42] Khoai môn phân bố rộng rãi khắp các vùng nhiệt đới và cận nhiệt đới ở Nam Á, Đông Á, Đông Nam Á và Papua New Guinea, miền bắc Australia và Maldives. Khoai môn có tính đa hình cao, khiến cho việc phân loại và phân biệt giữa loài hoang dã và trồng trọt trở nên khó khăn. Người ta tin rằng chúng đã được thuần hóa độc lập nhiều lần. Giới học giả đưa ra các địa điểm có thể là New Guinea, lục địa Đông Nam Á và đông bắc Ấn Độ, chủ yếu dựa trên phạm vi bản địa giả định của các loài thực vật hoang dã.[43][44][45] Tuy nhiên, nhiều nghiên cứu gần đây đã chỉ ra rằng khoai môn hoang dã có thể có phân bố bản địa lớn hơn nhiều so với những gì được tin tưởng trước đây và các kiểu nhân giống hoang dã cũng có thể là bản địa tại các khu vực khác của Đông Nam Á hải đảo.[46][47]

Dấu vết khảo cổ về hoạt động khai thác khoai môn đã được phục hồi từ nhiều địa điểm, mặc dù không thể xác định chắc chắn đây là loại được trồng hay hoang dã. Chúng bao gồm hang Niah ở Borneo khoảng 10.000 năm trước,[48] hang Ille ở Palawan, có niên đại ít nhất 11.000 năm trước;[48][49] đầm lầy Kuk ở New Guinea, có niên đại từ năm 8250 TCN đến 7960 TCN;[50][51] và hang Kilu ở Quần đảo Solomon có niên đại khoảng 28.000 đến 20.000 năm trước.[52] Trong trường hợp đầm lầy Kuk, có bằng chứng về nền nông nghiệp chính thức xuất hiện khoảng 10.000 năm trước, với bằng chứng về các thửa đất được canh tác, mặc dù loại cây nào được trồng vẫn chưa biết.[53]

Khoai môn được người Nam Đảo mang đến các đảo Thái Bình Dương từ khoảng năm 1300 TCN. Tại đây, chúng trở thành cây trồng chủ yếu của người Polynesia, cùng với các loại "khoai môn" khác, như Alocasia macrorrhizos, Amorphophallus paeoniifolius và Cyrtosperma merkusii. Chúng là cây quan trọng nhất và được ưa thích nhất trong số bốn loại vì ít khả năng chứa tinh thể hình kim gây khó chịu có trong các loại cây khác.[54][55] Khoai môn cũng được xác định là một trong những thực phẩm chủ yếu tại Micronesia, từ bằng chứng khảo cổ học có niên đại từ thời kỳ Latte tiền thuộc địa (khoảng 900 – 1521 SCN), cho biết rằng khoai cũng được người Micronesia mang theo khi họ xâm chiếm quần đảo.[56][57] Phấn hoa khoai môn và dư lượng tinh bột cũng đã được xác định tại địa điểm Lapita, có niên đại từ năm 1100 TCN đến năm 550 TCN.[58] Khoai môn sau đó được truyền đến Madagascar vào đầu thế kỷ I SCN.[59]

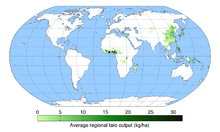

Sản xuất hiện đại[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Năm 2022, sản lượng khoai môn toàn thế giới là 18 triệu tấn, dẫn đầu là Nigeria với 46% tổng sản lượng (bảng).

Khoai môn có sản lượng lớn thứ năm trong số các loại cây lấy rễ và củ trên toàn thế giới.[60] Năng suất khoai môn bình quân khoảng 7 tấn/ha.[60]

Khoai môn có thể được trồng trên ruộng lúa nơi có nhiều nước hoặc ở vùng cao nơi được mưa rút nước hoặc tưới bổ sung. Khoai môn là một trong số ít cây trồng (cùng với lúa và sen) có thể trồng được trong điều kiện ngập nước. Canh tác ngập nước có vài lợi thế so với canh tác trên đất khô như: năng suất cao hơn (khoảng gấp đôi), sản xuất trái mùa (có thể dẫn đến giá cao hơn) và kiểm soát cỏ dại (tạo điều kiện ngập lụt thuận lợi).

| Sản xuất khoai môn – 2022 | |

|---|---|

| Quốc gia | (Triệu tấn ) |

| 8.2 | |

| 1.9 | |

| 1.9 | |

| 1.7 | |

| 1.7 | |

| Thế giới | 17,7 |

| Nguồn: FAOSTAT của Liên Hiệp Quốc [61] | |

Giống như hầu hết các loại cây trồng lấy củ, khoai môn và khoai sọ phát triển tốt ở vùng đất sâu, ẩm hoặc thậm chí đầm lầy, nơi có lượng mưa hàng năm vượt quá 2,500 mm (0,0984 in). Khoai sọ có khả năng chịu hạn hán và lạnh tốt hơn. Cây trồng đạt độ chín trong vòng 6 đến 12 tháng sau khi trồng tại vùng đất khô và sau 12 đến 15 tháng tại vùng đất ngập nước. Thu hoạch khi chiều cao cây giảm và lá chuyển vàng.

Kiểm soát chất lượng[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Khoai môn thường có giá thị trường cao hơn so với các loại cây lấy củ khác, vì vậy biện pháp kiểm soát chất lượng trong suốt quá trình sản xuất là khá cần thiết. Kích thước củ khoai tại hầu hết các thị trường là 1–2 kg và 2–3 kg. Kích thước tốt nhất để đóng gói và đến người tiêu dùng là 1–2 kg. Để đảm bảo sản phẩm đáp ứng các tiêu chuẩn cao như mong đợi khi đến tay người tiêu dùng, có một số tiêu chuẩn phân loại chung cho củ tươi:[62]

- Không dính đất dư thừa, mềm nhũn hoặc thối mục

- Không có vết thâm hoặc vết cắt sâu

- Hình cầu đến hình tròn

- Không có biến dạng bất thường lớn

- Không rễ

- Khoảng 5 cm (dưới 2”) cuống lá còn dính vào thân hành

- Không có cặp đỉnh

Do độ ẩm của củ khoai cao và tính ưa ẩm tự nhiên của cây, nấm mốc và bệnh tật có thể dễ dàng phát triển, gây mục hoặc thối rễ. Để kéo dài thời hạn sử dụng, củ thường được bảo quản ở nhiệt độ mát hơn, từ 10 đến 15 độ C và duy trì ở độ ẩm tương đối từ 80% đến 90%. Để đóng gói, thường đặt củ trong túi polypropylen hoặc thùng gỗ thông gió để giảm thiểu hơi nước ngưng tụ và 'đổ mồ hôi'. Trong quá trình xuất khẩu, khối lượng cho phép cao hơn khoảng 5% so với khối lượng tịnh sẽ được đưa vào để tính đến khả năng co rút trong quá trình vận chuyển. Đối với mục đích vận chuyển và xuất khẩu thương mại, thường dùng cách làm lạnh; ví dụ, củ có cuống lá còn lại từ 5 đến 10 cm được xuất khẩu từ Fiji sang New Zealand trong hộp gỗ. Sau đó chúng được vận chuyển qua container lạnh, làm lạnh đến khoảng 5°C.[63] Củ có thể được duy trì trong tình trạng tốt đến sáu tuần; hầu hết củ chất lượng tốt thậm chí có thể được người tiêu dùng trồng lại và phát triển nhờ vào tính chất sinh sôi và độ cứng của loài này.

Nhân giống[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Vào đầu những năm 1970, một trong những chương trình nhân giống khoai môn sớm nhất đã được khởi xướng ở Quần đảo Solomon nhằm tạo ra các giống có khả năng kháng bệnh bạc lá khoai môn. Sau khi bệnh bạc lá khoai môn du nhập vào Samoa vào năm 1993, một chương trình nhân giống khác đã được bắt đầu. Trong chương trình này, các giống châu Á kháng TLB đã được sử dụng. Chương trình nhân giống đã giúp khôi phục ngành xuất khẩu khoai môn ở Samoa.[64]

Năng suất và chất lượng củ dường như có mối tương quan nghịch. Để sản xuất ra những củ khoai tươi khỏe đồng đều mà thị trường mong muốn, có thể sử dụng các giống chín sớm với thời gian sinh trưởng từ 5 đến 7 tháng.[64]

Phương pháp và chương trình tuyển chọn[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Các giống trồng ở khu vực Thái Bình Dương tạo ra củ có chất lượng tốt là kết quả của việc chọn lọc chất lượng và năng suất củ. Tuy nhiên, nền tảng di truyền của những giống cây trồng này rất hẹp. Các giống châu Á có những đặc điểm không mong muốn về mặt nông nghiệp (chẳng hạn như chồi rễ mút và thân bò), nhưng dường như đa dạng hơn về mặt di truyền. Cần phải trao đổi quốc tế về nguồn gen khoai môn với các thủ tục kiểm dịch đáng tin cậy.[64]

Người ta cho rằng có 15.000 giống C. esculenta. Hiện tại có 6.000 mẫu đăng ký từ các viện nghiên cứu khác nhau trên khắp thế giới. INEA (Mạng lưới quốc tế về cây ráy ăn được) đã có mẫu lõi gồm 170 giống cây trồng được phân phối. Những giống cây này được nuôi dưỡng in vitro tại một trung tâm mầm nguyên sinh ở Fiji,[65] được xem là an toàn hơn và rẻ hơn so với bảo tồn trên đồng ruộng.[64]

Nhân giống đa bội[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Khoai môn tồn tại dưới dạng lưỡng bội (2n=28) và tam bội (3n=42). Giống tam bội xuất hiện tự nhiên ở Ấn Độ được cho là có năng suất tốt hơn đáng kể. Đã có những nỗ lực tạo ra thể tam bội nhân tạo bằng cách lai thể lưỡng bội với thể tứ bội nhân tạo.[64]

| Giá trị dinh dưỡng cho mỗi 100 g (3,5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Năng lượng | 594 kJ (142 kcal) |

34.6 g | |

| Đường | 0.49 |

| Chất xơ | 5.1 g |

0.11 g | |

0.52 g | |

| Vitamin | Lượng %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 9% 0.107 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2% 0.028 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 3% 0.51 mg |

| Acid pantothenic (B5) | 7% 0.336 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 19% 0.331 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 5% 19 μg |

| Vitamin C | 6% 5 mg |

| Vitamin E | 20% 2.93 mg |

| Chất khoáng | Lượng %DV† |

| Calci | 1% 18 mg |

| Sắt | 4% 0.72 mg |

| Magnesi | 7% 30 mg |

| Mangan | 20% 0.449 mg |

| Phosphor | 6% 76 mg |

| Kali | 16% 484 mg |

| Kẽm | 2% 0.27 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Nước | 64 g |

| † Tỷ lệ phần trăm được ước tính dựa trên khuyến nghị Hoa Kỳ dành cho người trưởng thành,[66] ngoại trừ kali, được ước tính dựa trên khuyến nghị của chuyên gia từ Học viện Quốc gia.[67] | |

| Giá trị dinh dưỡng cho mỗi 100 g (3,5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Năng lượng | 177 kJ (42 kcal) |

6.7 g | |

| Đường | 3 g |

| Chất xơ | 3.7 g |

0.74 g | |

5 g | |

| Vitamin | Lượng %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 27% 241 μg27% 2895 μg1932 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 17% 0.209 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 35% 0.456 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 9% 1.513 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 9% 0.146 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 32% 126 μg |

| Vitamin C | 58% 52 mg |

| Vitamin E | 13% 2.02 mg |

| Vitamin K | 91% 108.6 μg |

| Chất khoáng | Lượng %DV† |

| Calci | 8% 107 mg |

| Sắt | 13% 2.25 mg |

| Magnesi | 11% 45 mg |

| Mangan | 31% 0.714 mg |

| Phosphor | 5% 60 mg |

| Kali | 22% 648 mg |

| Kẽm | 4% 0.41 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Nước | 86 g |

| † Tỷ lệ phần trăm được ước tính dựa trên khuyến nghị Hoa Kỳ dành cho người trưởng thành,[66] ngoại trừ kali, được ước tính dựa trên khuyến nghị của chuyên gia từ Học viện Quốc gia.[67] | |

Dinh dưỡng[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Khoai môn nấu chín có 64% nước, 35% carbohydrat, chứa lượng protein và chất béo không đáng kể (bảng). Với lượng tham chiếu là 100 g (3,5 oz), khoai môn cung cấp 142 calo năng lượng thực phẩm và là nguồn giàu (20% hoặc hơn giá trị hàng ngày, DV) vitamin B6 (25% DV), vitamin E (20% DV) và mangan (21% DV), trong khi phosphor và kali ở mức vừa phải (10-11% DV) (bảng).

Lá khoai môn thô chứa 86% nước, 7% carbohydrat, 5% protein và 1% chất béo (bảng). Lá rất giàu dinh dưỡng, chứa một lượng đáng kể vitamin và khoáng chất, đặc biệt là vitamin K ở mức 103% DV (bảng).

Công dụng[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Ẩm thực[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Khoai môn là một loại thực phẩm thiết yếu ở các nền văn hóa châu Phi, châu Đại Dương và Nam Á.[68] Người ta thường ăn thân và lá của cây. Củ có màu tím nhạt do sắc tố phenolic,[69] được rang, nướng hoặc luộc. Đường tự nhiên mang lại hương vị ngọt ngào, hấp dẫn. Tinh bột dễ tiêu hóa, hạt mịn và nhỏ nên thường được dùng làm thức ăn cho trẻ nhỏ.

Ở dạng thô, cây có độc hại do sự hiện diện của calci oxalat[70][71] và sự hiện diện của tinh thể hình kim trong tế bào thực vật. Tuy nhiên, độc tố có thể được giảm thiểu và củ sẽ ngon miệng hơn bằng cách nấu chín,[72] hoặc ngâm trong nước lạnh qua đêm.

Củ của giống cây tròn, nhỏ được gọt vỏ và luộc chín, sau đó được bán ở dạng đông lạnh, đóng gói trong chất lỏng riêng hoặc đóng hộp.

Châu Đại Dương[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Quần đảo Cook[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Khoai môn là cây trồng nổi bật của Quần đảo Cook và vượt trội tất cả cây trồng khác về diện tích đất dành cho sản xuất. Sự nổi bật của cây trồng đã khiến chúng trở thành thực phẩm thiết yếu trong chế độ ăn của người dân. Khoai môn được trồng trên khắp đất nước, nhưng phương pháp canh tác phụ thuộc vào tính chất của hòn đảo nơi trồng khoai. Khoai môn cũng đóng một vai trò quan trọng trong thương mại xuất khẩu của đất nước.[73] Rễ được luộc để ăn, theo tiêu chuẩn trên khắp Polynesia. Lá khoai môn còn được dùng để ăn, nấu với nước cốt dừa, hành, thịt hoặc cá.[74]

Fiji[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Khoai môn (dalo trong tiếng Fiji) là thực phẩm chính trong chế độ ăn của người Fiji trong nhiều thế kỷ và tầm quan trọng về mặt văn hóa của khoai được tôn vinh vào Ngày khoai môn. Chúng phát triển như một cây trồng xuất khẩu bắt đầu vào năm 1993 khi bệnh bạc lá khoai môn[75] tàn phá ngành công nghiệp khoai môn ở nước láng giềng Samoa. Fiji đã lấp đầy khoảng trống và sớm cung cấp khoai môn trên phạm vi quốc tế. Gần 80% khoai môn xuất khẩu của Fiji đến từ đảo Taveuni, nơi không có mặt loài bọ khoai môn Papuana uninodis. Công nghiệp khoai môn Fiji trên các đảo chính Viti Levu và Vanua Levu liên tục phải đối mặt với thiệt hại do bọ cánh cứng gây ra. Bộ Nông nghiệp Fiji và Phòng Tài nguyên Đất đai của Ban Thư ký Cộng đồng Thái Bình Dương (SPC) đang nghiên cứu kiểm soát dịch hại và tiến hành các biện pháp hạn chế kiểm dịch để ngăn chặn dịch hại lây lan. Taveuni hiện đang xuất khẩu các loại cây trồng không bị sâu bệnh gây hại.

Hawaii[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Kalo là tên trong tiếng Hawaii của khoai môn. Cây trồng địa phương đóng vai trò quan trọng trong văn hóa và thần thoại Hawaii. Khoai môn là thực phẩm thiết yếu truyền thống của ẩm thực bản địa Hawaii. Một số cách chế biến khoai môn gồm có poi, khoai môn hấp và dùng như khoai tây, lát mỏng chiên và lá lūʻau (để làm laulau). Ở Hawaii, khoai môn được trồng trong điều kiện đất khô hoặc đất ngập nước. Trồng khoai môn tại đó gặp nhiều thách thức vì khó tiếp cận nguồn nước ngọt. Khoai môn thường được trồng ở các “ruộng ao” được gọi là loʻi. Giống cây chịu đất khô hoặc "đất cao" điển hình (giống trồng trên ruộng có nước nhưng không bị ngập nước) là lehua maoli và bun long, loại sau được biết đến rộng rãi là "khoai môn Trung Quốc". Bun long được dùng để làm khoai môn lát mỏng chiên. Dasheen (còn gọi là "eddo") là một giống chịu đất khô khác được trồng để lấy thân củ hoặc làm cây cảnh. Chế độ ăn đương đại của người Hawaii bao gồm nhiều loại cây có củ, đặc biệt là khoai lang và khoai môn.

Cơ quan Thống kê Nông nghiệp Hawaii xác định sản lượng khoai môn trung bình trong 10 năm là khoảng 6,1 triệu pound (2.800 tấn).[76] Tuy nhiên, sản lượng khoai môn năm 2003 chỉ đạt 5 triệu pound (2.300 tấn), mức thấp nhất kể từ khi bắt đầu ghi chép vào năm 1946. Mức thấp trước đó (1997) là 5,5 triệu pound (2.500 tấn). Mặc dù nhu cầu nhìn chung ngày càng tăng nhưng sản lượng thậm chí còn thấp hơn vào năm 2005—chỉ 4 triệu pound, trong đó khoai môn để chế biến thành poi chiếm 97,5%.[77] Đô thị hóa là một nguyên nhân làm giảm sản lượng mùa vụ từ mức cao nhất vào năm 1948 là 14,1 triệu pound (6.400 tấn), nhưng gần đây, sự suy giảm này là do sâu bệnh. Một loài ốc táo phi bản địa (Pomacea Canaliculata) là thủ phạm chính cùng với bệnh thối cây bắt nguồn từ một loài nấm thuộc chi Phytophthora hiện đang gây hại cho vụ mùa khoai môn trên khắp Hawaii. Mặc dù thuốc trừ sâu có thể kiểm soát cả hai vấn đề ở một mức độ nào đó nhưng sử dụng thuốc trừ sâu ở loʻi bị cấm vì hóa chất có khả năng di chuyển nhanh chóng vào suối và cuối cùng ra biển.[76][77]

Vai trò xã hội[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Important aspects of Hawaiian culture revolve around kalo. For example, the newer name for a traditional Hawaiian feast, the lūʻau, comes from kalo. Young kalo tops baked with coconut milk and chicken meat or octopus arms are frequently served at luaus.[78]

By ancient Hawaiian custom, fighting is not allowed when a bowl of poi is "open". It is also disrespectful to fight in front of an elder and one should not raise their voice, speak angrily, or make rude comments or gestures.

Loʻi[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

A loʻi is a patch of wetland dedicated to growing kalo. Hawaiians have traditionally used irrigation to produce kalo. Wetland fields often produce more kalo per acre than dry fields.[79] Wetland-grown kalo need a constant flow of water.

About 300 varieties of kalo were originally brought to Hawaiʻi (about 100 remain). The kalo plant takes seven months to grow until harvest, so lo`i fields are used in rotation and the soil can be replenished while the loʻi in use has sufficient water. Stems are typically replanted in the lo`i for future harvests.

History[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

One mythological version of Hawaiian ancestry cites the taro plant as an ancestor to Hawaiians. Legend joins two siblings of high and divine rank: Papahānaumoku ("Papa from whom lands are born", or Earth mother) and Wākea (Sky father). Together they create the islands of Hawaii and a beautiful woman, Hoʻohokukalani (The Heavenly one who made the stars).[80]

The story of kalo begins when Wakea and Papa conceived their daughter, Hoʻohokukalani. Daughter and father then conceived a child together named Hāloanakalaukapalili (Long stalk trembling), but it was stillborn. After the father and daughter buried the child near their house, a kalo plant grew over the grave:[81]

The stems were slender and when the wind blew they swayed and bent as though paying homage, their heart-shaped leaves shivering gracefully as in hula. And in the center of each leaf water gathered, like a mother’s teardrop.[82]

The second child born of Wākea and Hoʻohokukalani was named Hāloa after his older brother. The kalo of the earth was the sustenance for the young brother and became the principal food for successive generations.[83] The Hawaiian word for family, ʻohana, is derived from ʻohā, the shoot that grows from the kalo corm. As young shoots grow from the corm of the kalo plant, so people, too, grow from their family.[84]

Papua New Guinea[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

The taro corm is a traditional staple crop for large parts of Papua New Guinea, with a domestic trade extending its consumption to areas where it is not traditionally grown. Taro from some regions has developed particularly good reputations with (for instance) Lae taro being highly prized.

Among the Urapmin people of Papua New Guinea, taro (known in Urap as ima) is the main source of sustenance along with the sweet potato (Urap: wan). In fact, the word for "food" in Urap is a compound of these two words.[85]

Polynesia[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Considered the staple starch of traditional Polynesian cuisine, taro is both a common and prestigious food item that was first introduced to the Polynesian islands by prehistoric seafarers of Southeast Asian derivation. The tuber itself is prepared in various ways, including baking, steaming in earth ovens (umu or imu), boiling, and frying. The famous Hawaiian staple poi is made by mashing steamed taro roots with water. Taro also features in traditional desserts such as Samoan fa'ausi, which consists of grated, cooked taro mixed with coconut milk and brown sugar. The leaves of the taro plant also feature prominently in Polynesian cooking, especially as edible wrappings for dishes such as Hawaiian laulau, Fijian and Samoan palusami (wrapped around onions and coconut milk), and Tongan lupulu (wrapped corned beef). Ceremonial presentations on occasion of chiefly rites or communal events (weddings, funerals, etc.) traditionally included the ritual presentation of raw and cooked taro roots/plants.

The Hawaiian laulau traditionally contains pork, fish, and lu'au (cooked taro leaf). The wrapping is inedible ti leaves (Hawaiian: lau ki). Cooked taro leaf has the consistency of cooked spinach and is therefore unsuitable for use as a wrapping.

Samoa[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Samoa, the baby talo leaves and coconut milk are wrapped into parcels and cooked, along with other food, in an earth oven . The parcels are called palusami or lu'au. The resulting taste is smoky, sweet, savory and has a unique creamy texture. The root is also baked (Talo tao) in the umu or boiled with coconut cream (Faálifu Talo). It has a slightly bland and starchy flavor. It is sometimes called the Polynesian potato.

Tonga[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Lū is the Tongan word for the edible leaves of the taro plant (called talo in Tonga), as well as the traditional dish made using them. This meal is still prepared for special occasions and especially on Sunday. The dish consists of chopped meat, onions, and coconut milk wrapped in a number of taro leaves (lū talo). This is then wrapped traditionally in a banana leaf (nowadays, aluminum foil is often used) and put in the ʻumu to cook. It has a number of named varieties, dependent on the filling:

- Lū pulu – lū with beef, commonly using imported corned beef (kapapulu)

- Lū sipi – lū with lamb

- Lū moa – lū with chicken

- Lū hoosi – lū with horse meat

Oceanian Atolls

The islands situated along the border of the three main parts of Oceania (Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia) are more prone to being atolls rather than volcanic islands (most prominently Tuvalu, Tokelau, and Kiribati). As a result of this, Taro was not a part of the traditional diet due to the infertile soil and have only become a staple today through importation from other islands (Taro and Cassava cultivars are usually imported from Fiji or Samoa). The traditional staple however is the Swamp Taro known as Pulaka or Babai, a distant relative of the Taro but with a very long growing phase (3–5 years), larger and denser corms and coarser leaves. It is grown in a patch of land dug out to give rise to the freshwater lense beneath the soil. The lengthy growing time of this crop usually confines it as a food during festivities much like Pork although it can be preserved by drying out in the sun and storing it somewhere cool and dry to be enjoyed out of harvesting season.

East Asia[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

China[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Taro (giản thể: 芋头; phồn thể: 芋頭; bính âm: yùtou; Yale Quảng Đông: wuhtáu) is commonly used as a main course as steamed taro with or without sugar, as a substitute for other cereals, in Chinese cuisine in a variety of styles and provinces steamed, boiled or stir-fried as a main dish and as a flavor-enhancing ingredient. In Northern China, it is often boiled or steamed then peeled and eaten with or without sugar much like a potato. It is commonly braised with pork or beef. It is used in the Cantonese dim sum to make a small plated dish called taro dumpling as well as a pan-fried dish called taro cake. It can also be shredded into long strips which are woven together to form a seafood birdsnest. In Fujian cuisine, it is steamed or boiled and mixed with starch to form a dough for dumpling.

Taro cake is a delicacy traditionally eaten during Chinese New Year celebrations. As a dessert, it can be mashed into a purée or used as a flavoring in tong sui, ice cream, and other desserts such as Sweet Taro Pie. McDonald's sells taro-flavored pies in China.

Taro is mashed in the dessert known as taro purée.

Taro paste, a traditional Cantonese cuisine, which originated from the Chaoshan region in the eastern part of China's Guangdong Province is a dessert made primarily from taro. The taro is steamed and then mashed into a thick paste, which forms the base of the dessert. Lard or fried onion oil is then added for fragrance. The dessert is traditionally sweetened with water chestnut syrup, and served with ginkgo nuts. Modern versions of the dessert include the addition of coconut cream and sweet corn. The dessert is commonly served at traditional Teochew wedding banquet dinners as the last course, marking the end of the banquet.

Japan[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

A similar plant in Japan is called satoimo (里芋、サトイモ satoimo, literally "village potato"). The "child" and "grandchild" corms (cormels, cormlets) which bud from the parent satoimo, are called koimo (子芋 koimo) and magoimo (孫芋 magoimo), respectively, or more generally imonoko (芋の子 imonoko). Satoimo has been propagated in Southeast Asia since the late Jōmon period. It was a regional staple before rice became predominant. The tuber, satoimo, is often prepared through simmering in fish stock (dashi) and soy sauce. The stalk, zuiki, can also be prepared a number of ways, depending on the variety.[86]

Korea[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Korea, taro is called toran (tiếng Triều Tiên: 토란: "earth egg"), and the corm is stewed and the leaf stem is stir-fried. Taro roots can be used for medicinal purposes, particularly for treating insect bites. It is made into the Korean traditional soup toranguk (토란국). Taro stems are often used as an ingredient in yukgaejang (육개장).

Taiwan[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Taiwan, taro—yùtóu (芋頭) in Mandarin, and ō͘-á (芋仔) in Taiwanese—is well-adapted to Taiwanese climate and can grow almost anywhere in the country with minimal maintenance. Before the Taiwan Miracle made rice affordable to everyone, taro was one of the main staples in Taiwan. Nowadays taro is used more often in desserts. Supermarket varieties range from about the size and shape of a brussels sprout to longer, larger varieties the size of a football. Taro chips are often used as a potato-chip-like snack. Compared to potato chips, taro chips are harder and have a nuttier flavor. Another popular traditional Taiwanese snack is taro ball, served on ice or deep-fried. It is common to see taro as a flavor in desserts and drinks, such as bubble tea.

Southeast Asia[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Indonesia[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Indonesia, taro is widely used for snacks, cakes, crackers, and even macarons, thus it can be easily found everywhere. Some varieties are specially cultivated in accordance with social or geographical traditions. Taro is usually known as "keladi", although other varieties are also known as "talas", among others. The vegetable soup, sayur asem and sayur lodeh may use taro and its leaves also lompong (taro stem) in Java. Chinese descendants in Indonesia often eat taro with stewed rice and dried shrimp. The taro is diced and cooked along with the rice, the shrimp, and sesame oil. In New Guinea, there are some traditional dishes made of taro as well its leaves such as keripik keladi (sweet spicy taro chips), keladi tumbuk, pounded taro with vegetables, and aunu senebre, anchovies mixed with slices of taro leaf. Mentawai people has a traditional food called lotlot, taro leaves cooked with tinimbok (smoked fish).

Philippines[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In the Philippines taro is usually called gabi, abi, or avi and is widely available throughout the archipelago. Its adaptability to marshland and swamps make it one of the most common vegetables in the Philippines. The leaves, stems, and corms are all consumed and form part of the local cuisine. A popular recipe for taro is laing from the Bicol Region; the dish's main ingredients are taro leaves (at times including stems) cooked in coconut milk, and salted with fermented shrimp or fish bagoong.[87] It is sometimes heavily spiced with red hot chilies called siling labuyo. Another dish in which taro is commonly used is the Philippine national stew, sinigang, although radish can be used if taro is not available. This stew is made with pork and beef, shrimp, or fish, a souring agent (tamarind fruit, kamias, etc.) with the addition of peeled and diced corms as thickener. The corm is also prepared as a basic ingredient for ginataan, a coconut milk and taro dessert.

Thailand[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Thai cuisine, taro tiếng Thái: เผือก (pheuak) is used in a variety of ways depending on the region. Boiled taro is readily available in the market packaged in small cellophane bags, already peeled and diced, and eaten as a snack. Pieces of boiled taro with coconut milk are a traditional Thai dessert.[88] Raw taro is also often sliced and deep fried and sold in bags as chips (เผือกทอด). As in other Asian countries, taro is a popular flavor for ice cream in Thailand.[89]

Vietnam[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Vietnam, there is a large variety of taro plants. One is called khoai môn, which is used as a filling in spring rolls, cakes, puddings and sweet soup desserts, smoothies and other desserts. Taro is used in the Tết dessert chè khoai môn, which is sticky rice pudding with taro roots. The stems are also used in soups such as canh chua. One is called khoai sọ, which is smaller in size than khoai môn. Another common taro plant grows roots in shallow waters and grows stems and leaves above the surface of the water. This taro plant has saponin-like substances that cause a hot, itchy feeling in the mouth and throat. Northern farmers used to plant them to cook the stems and leaves to feed their hogs. They re-grew quickly from their roots. After cooking, the saponin in the soup of taro stems and leaves is reduced to a level the hogs can eat. Today this practice is no longer popular in Vietnam agriculture. These taro plants are commonly called khoai ngứa, which literally means "itchy potato".

South Asia[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Taro roots are commonly known as Arbi or Arvi in Urdu and Hindi language. It is a common dish in Northern India and Pakistan. Arbi Gosht (meat) Masala Recipe is a tangy mutton curry recipe with taro vegetable. Mutton and Arbi is cooked in whole spices and tomatoes which lends a wonderful taste to the dish.[90]

Bangladesh[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Bangladesh taro is a very popular vegetable known as kochu (কচু) or mukhi (মুখি). Within the Sylheti language, it is called mukhi. It is usually cooked with small prawns or the ilish fish into a curry, but some dishes are cooked with dried fish. Its green leaves, kochu pata (কচু পাতা), and stem, kochu (কচু), are also eaten as a favorite dish and usually ground to a paste or finely chopped to make shak — but it must be boiled well beforehand. Taro stolons or stems, kochur loti (কচুর লতি), are also favored by Bangladeshis and cooked with shrimp, dried fish or the head of the ilish fish.[91] Taro is available, either fresh or frozen, in the UK and US in most Asian stores and supermarkets specialising in Sylheti, Bangladeshi or South Asian food. Also, another variety called maan kochu is consumed and is a rich source of vitamins and nutrients. Maan Kochu is made into a paste and fried to prepare a food known as Kochu Bata.

India[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In India, taro or eddoe is a common dish served in many ways.

In Gujarat, it is called Patar Vel or Saryia Na Paan green leaves are used by making a roll, with besan (gram flour), salt, turmeric, red chili powder all put into paste form inside leaves. Then steamed and in small portions, as well as fried in the deep fryer.

In Mizoram, in north-eastern India, it is called bäl; the leaves, stalks and corms are eaten as dawl bai. The leaves and stalks are often traditionally preserved to be eaten in dry season as dawl rëp bai.[92][93]

In Assam, a north-eastern state, taro is known as kosu (কচু). Various parts of the plant are eaten by making different dishes. The leaf buds called kosu loti (কচু লতি) are cooked with sour dried fruits and called thekera (থেকেৰা) or sometimes eaten alongside tamarind, elephant apple, a small amount of pulses, or fish. Similar dishes are prepared from the long root-like structures called kosu thuri. A sour fried dish is made from its flower (kosu kala). Porridges are made from the corms themselves, which may also be boiled, seasoned with salt and eaten as snacks.

In Manipur, another north-eastern state, taro is known as pan. The Kukis calls it bal. Boiled bal is a snack at lunch along with chutney or hot chili-flakes besides being cooked as a main dish along with smoked or dried meat, beans, and mustard leaves. Sun-dried taro leaves are later used in broth and stews. It is widely available and is eaten in many forms, either baked, boiled, or cooked into a curry with hilsa or with fermented soybeans called hawai-zaar. The leaves are also used in a special traditional dish called utti, cooked with peas.

It is called arbi in Urdu/Hindi and arvi in Punjabi in north India. It is called kəchu (कचु) in Sanskrit.[94]

In Himachal Pradesh, in northern India, taro corms are known as ghandyali, and the plant is known as kachalu in the Kangra and Mandi districts. The dish called patrodu is made using taro leaves rolled with corn or gram flour and boiled in water. Another dish, pujji is made with mashed leaves and the trunk of the plant and ghandyali or taro corms are prepared as a separate dish. In Shimla, a pancake-style dish, called patra or patid, is made using gram flour.

In Uttarakhand and neighboring Nepal, taro is considered a healthy food and is cooked in a variety of ways. The delicate gaderi (taro variety) of Kumaon, especially from Lobanj, Bageshwar district, is much sought after. Most commonly it is boiled in tamarind water until tender, then diced into cubes which are stir-fried in mustard oil with fenugreek leaves. Another technique for preparation is boiling it in salt water till it is reduced to a porridge. The young leaves called gaaba, are steamed, sun-dried, and stored for later use. Taro leaves and stems are pickled. Crushed leaves and stems are mixed with de-husked urad daal (black lentils) and then dried as small balls called badi. These stems may also be sun-dried and stored for later use. On auspicious days, women worship saptarshi ("seven sages") and only eat rice with taro leaves.

In Maharashtra, in western India, the leaves, called alu che paana, are de-veined and rolled with a paste of gram flour. Then seasoned with tamarind paste, red chili powder, turmeric, coriander, asafoetida and salt, and finally steamed. These can be eaten whole, cut into pieces, or shallow fried and eaten as a snack known as alu chi wadi. Alu chya panan chi patal bhaji a lentil and colocasia leaves curry, is also popular. In Goan as well as Konkani cuisine taro leaves are very popular. A tall-growing variety of taro is extensively used on the western coast of India to make patrode, patrade, or patrada (lit. "leaf-pancake") a dish with gram flour, tamarind and other spices.

In Gujarat, it is called patar vel or saryia na paan. Gram flour, salt, turmeric, red chili powder made into paste and stuffed inside a roll of green taro leaves. Then steamed and in small portions and then fried.[95]

Sindhis call it kachaloo; they fry it, compress it, and re-fry it to make a dish called tuk which complements Sindhi curry.

In Kerala, a state in southern India, taro corms are known as chembu kizhangu (ചേമ്പ് കിഴങ്ങ്) and are a staple food, a side dish, and an ingredient in various side dishes like sambar. As a staple food, it is steamed and eaten with a spicy chutney of green chilies, tamarind, and shallots. The leaves and stems of certain varieties of taro are also used as a vegetable in Kerala. In Dakshin Kannada in Karnataka, it is used as a breakfast dish, either made like fritters or steamed.

In Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, taro corms are known as sivapan-kizhangu (seppankilangu or cheppankilangu), chamagadda, or in coastal Andhra districts as chaama dumpa. They can be prepared in a variety of ways, such as by deep-frying the steamed and sliced corms in oil known as chamadumpa chips to be eaten on the side with rice, or cooking in a tangy tamarind sauce with spices, onion, and tomato.

In the east Indian state of West Bengal, taro corms are thinly sliced and fried to make chips called kochu bhaja(কচু ভাজা). The stem is used to cook kochur saag (কচুর শাগ) with fried hilsha (ilish) head or boiled chhola (chickpea), often eaten as a starter with hot rice. The corms are also made into a paste with spices and eaten with rice. The most popular dish is a spicy curry made with prawn and taro corms. Gathi kochu (গাঠি কচু) (taro variety) are very popular and used to make a thick curry called gathi kochur dal (গাঠি কচুর ডাল). Here kochur loti (কচুর লতি) (taro stolon) dry curry[96] is a popular dish which is usually prepared with poppy seeds and mustard paste. Leaves and corms of shola kochu (শলা কচু) and maan kochu (মান কচু) are also used to make some popular traditional dishes.

In Mithila, Bihar, taro corms are known as ədua (अडुआ) and its leaves are called ədikunch ke paat (अड़िकंच के पात). A curry of taro leaves is made with mustard paste and sour sun-dried mango pulp (आमिल; aamil).

In Odisha, taro corms are known as saru. Dishes made of taro include saru besara (taro in mustard and garlic paste). It is also an indispensable ingredient in preparing dalma, an Odia cuisine staple (vegetables cooked with dal). Sliced taro corms, deep fried in oil and mixed with red chili powder and salt, are known as saru chips.

Maldives[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Ala was widely grown in the southern atolls of Addu Atoll, Fuvahmulah, Huvadhu Atoll, and Laamu Atoll and is considered a staple even after rice was introduced. Ala and olhu ala are still widely eaten all over the Maldives, cooked or steamed with salt to taste, and eaten with grated coconut along with chili paste and fish soup. It is also prepared as a curry. The corms are sliced and fried to make chips and are also used to prepare varieties of sweets.[97]

Nepal[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Taro is grown in the Terai and the hilly regions of Nepal. The root (corm) of taro is known as pindalu (पिँडालु) and petioles with leaves are known as karkalo (कर्कलो), Gava (गाभा) and also Kaichu (केेेैचु) in Maithili. Almost all parts are eaten in different dishes. Boiled corm of Taro is commonly served with salt, spices, and chilies. Taro is a popular dish in the hilly region. Chopped leaves and petioles are mixed with Urad bean flour to make dried balls called maseura (मस्यौरा). Large taro leaves are used as an alternative to an umbrella when unexpected rain occurs. Popular attachment to taro since ancient times is reflected in popular culture, such as in songs and textbooks. Jivan hamro karkala ko pani jastai ho (जीवन हाम्रो कर्कलाको पानी जस्तै हो) means, "Our life is as vulnerable as water stuck in the leaf of taro".

Taro is cultivated and eaten by the Tharu people in the Inner Terai as well. Roots are mixed with dried fish and turmeric, then dried in cakes called sidhara which are curried with radish, chili, garlic and other spices to accompany rice. The Tharu prepare the leaves in a fried vegetable side-dish that also shows up in Maithili cuisine.[98]

Pakistan[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Pakistan, taro or eddoe or arvi is a very common dish served with or without gravy; a popular dish is arvi gosht, which includes beef, lamb or mutton. The leaves are rolled along with gram flour batter and then fried or steamed to make a dish called Pakora, which is finished by tempering with red chilies and carrom (ajwain) seeds. Taro or arvi is also cooked with chopped spinach. The dish called Arvi Palak is the second most renowned dish made of Taro.

Sri Lanka[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Many varieties are recorded in Sri Lanka, several being edible, most being toxic to humans and, therefore, are not grown. Edible varieties (such as kiri ala, kolakana ala, gahala, and sevel ala) are grown for their corms and leaves. Sri Lankans eat corms after boiling them or making them into a curry with coconut milk. Some varieties of the leaves of , kolakana ala and kalu alakola are eaten.

Middle East and Europe[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Taro was consumed by the early Romans in much the same way the potato is today. They called this root vegetable colocasia. The Roman cookbook Apicius mentions several methods for preparing taro, including boiling, preparing with sauces, and cooking with meat or fowl. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the use of taro dwindled in Europe. This was largely due to the decline of trade and commerce with Egypt, previously controlled by Rome. When the Spanish and Portuguese sailed to the new world, they brought taro along with them. Recently[khi nào?] there has been renewed interest in exotic foods and consumption is increasing.

Cyprus[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Cyprus, taro has been in use since the time of the Roman Empire.[99][100] Today it is known as kolokas in Turkish or kolokasi (κολοκάσι) in Greek, which comes from the Ancient Greek name κολοκάσιον (kolokasion) for lotus root. It is usually sauteed with celery and onion with pork, chicken or lamb, in a tomato sauce – a vegetarian version is also available. The cormlets are called poulles (sing. poulla), and they are prepared by first being sauteed, followed by decaramelising the vessel with dry red wine and coriander seeds, and finally served with freshly squeezed lemon.[101]

Greece[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Greece, taro grows on Icaria. Icarians credit taro for saving them from famine during World War II. They boil it until tender and serve it as a salad.

Lebanon[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Lebanon, taro is known as kilkass and is grown mainly along the Mediterranean coast. The leaves and stems are not consumed in Lebanon and the variety grown produces round to slightly oblong tubers that vary in size from a tennis ball to a small cantaloupe. Kilkass is a very popular winter dish in Lebanon and is prepared in two ways: kilkass with lentils is a stew flavored with crushed garlic and lemon juice and ’il’as (Lebanese pronunciation of قلقاس) bi-tahini. Another common method of preparing taro is to boil, peel then slice it into 1 cm (1⁄2 in) thick slices, before frying and marinating in edible "red" sumac. In northern Lebanon, it is known as a potato with the name borshoushi (el-orse borshushi). It is also prepared as part of a lentil soup with crushed garlic and lemon juice. Also in the north, it is known by the name bouzmet, mainly around Menieh, where it is first peeled, and left to dry in the sun for a couple of days. After that, it is stir-fried in lots of vegetable oil in a casserole until golden brown, then a large amount of wedged, melted onions are added, in addition to water, chickpeas and some seasoning. These are all left to simmer for a few hours, and the result is a stew-like dish. It is considered a hard-to-make delicacy, not only because of the tedious preparation but the consistency and flavour that the taro must reach. The smaller variety of taro is more popular in the north due to its tenderness.

Portugal[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In the Azores taro is known as inhame or inhame-coco and is commonly steamed with potatoes, vegetables and meats or fish. The leaves are sometimes cooked into soups and stews. It is also consumed as a dessert after first being steamed and peeled, then fried in vegetable oil or lard, and finally sprinkled with sugar, cinnamon and nutmeg. Taro grows abundantly in the fertile land of the Azores, as well as in creeks that are fed by mineral springs. Through migration to other countries, the inhame is found in the Azorean diaspora.

Turkey[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Taro (tiếng Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ: gölevez) is grown in the south coast of Turkey, especially in Mersin, Bozyazı, Anamur and Antalya. It is boiled in a tomato sauce or cooked with meat, beans and chickpeas. It is often used as a substitute for potato.

Africa[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Egypt[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Egypt, taro is known as qolqas (tiếng Ả Rập Ai Cập: قلقاس, IPA: [ʔolˈʔæːs]). The corms are larger than what would be found in North American supermarkets. After being peeled completely, it is cooked in one of two ways: cut into small cubes and cooked in broth with fresh coriander and chard and served as an accompaniment to meat stew, or sliced and cooked with minced meat and tomato sauce.[102]

Canarias[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Taro has remained popular in the Canary Islands where it is known as ñame and is often used in thick vegetable stews, like potaje de berros (cress potage)[103] or simply boiled and seasoned with mojo or honey. In Canarian Spanish the word Ñame refers to Taro, while in other variants of Castilian is normally used to designate yams.

East Africa[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, taro is commonly known as arrow root, yam, amayuni (plural) or ejjuni (singular), ggobe, or nduma and madhumbe in some local Bantu languages. There are several varieties and each variety has its own local name. It is usually boiled and eaten with tea or other beverages, or as the main starch of a meal. It is also cultivated in Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe.

South Africa[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

It is known as amadumbe (plural) or idumbe (singular) in the Zulu language of Southern Africa.

West Africa[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Taro is consumed as a staple crop in West Africa, particularly in Ghana, Nigeria and Cameroon. It is called cocoyam in Nigeria, Ghana and Anglophone Cameroon, macabo in Francophone Cameroon, in Democratic Republic of Congo or Republic of Congo mbálá ya makoko, mankani in Hausa language, koko and lambo in Yoruba, and ede in Igbo language. Cocoyam is often boiled, fried, or roasted and eaten with a sauce. In Ghana, it substitutes for plantain in making fufu when plantains are out of season. It is also cut into small pieces to make a soupy baby food and appetizer called mpotompoto. It is also common in Ghana to find cocoyam chips (deep-fried slices, about 1 mm (1⁄32 in) thick). Cocoyam leaves, locally called kontomire in Ghana, are a popular vegetable for local sauces such as palaver sauce and egusi/agushi stew.[104] It is also commonly consumed in Guinea and parts of Senegal, as a leaf sauce or as a vegetable side, and is referred to as jaabere in the local Pulaar dialect.

Americas[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Brazil[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Lusophone countries, inhame (pronounced phát âm tiếng Bồ Đào Nha: [ĩ ˈɲɐ̃mi], phát âm tiếng Bồ Đào Nha: [ˈɲɐ̃mi] or phát âm tiếng Bồ Đào Nha: [ĩ ˈɲɐ̃mi], literally "yam") and cará are the common names for various plants with edible parts of the genera Alocasia, Colocasia (family Araceae) and Dioscorea (family Dioscoreaceae), and its respective starchy edible parts, generally tubers, with the exception of Dioscorea bulbifera, called cará-moela (pronounced phát âm tiếng Bồ Đào Nha: [kɐˈɾa muˈɛlɐ], literally, "gizzard yam"), in Brazil and never deemed to be an inhame. Definitions of what constitutes an inhame and a cará vary regionally, but the common understanding in Brazil is that carás are potato-like in shape, while inhames are more oblong.

In the Brazilian Portuguese of the hotter and drier Northeastern region, both inhames and carás are called batata (literally, "potato"). For differentiation, potatoes are called batata-inglesa (literally, "English potato"), a name used in other regions and sociolects to differentiate it from the batata-doce, "sweet potato", ironic names since both were first cultivated by the indigenous peoples of South America, their native continent, and only later introduced in Europe by the colonizers.

Taros are often prepared like potatoes, eaten boiled, stewed or mashed, generally with salt and sometimes garlic as a condiment, as part of a meal (most often lunch or dinner).

Central America[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Belize, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Panama, taro is eaten in soups, as a replacement for potatoes, and as chips. It is known locally as malanga (also malanga coco), a word of Bantu origin, and dasheen in Belize and Costa Rica, quiquizque in Nicaragua, and as otoe in Panama.

Haiti[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Haiti, it is usually called malanga, or taro. The corm is grated into a paste and deep-fried to make a fritter called Acra. Acra is a very popular street food in Haiti.

Jamaica[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Jamaica, taro is known as coco, cocoyam and dasheen. Corms with flesh which is white throughout are referred to as minty-coco. The leaves are also used to make Pepper Pot Soup which may include callaloo.

Suriname[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Suriname it is called tayer, taya, pomtayer or pongtaya. The taro root is called aroei by the indigenous Surinamese and is commonly known as "Chinese tayer". The variety known as eddoe is also called Chinese tayer. It is a popular cultivar among the Maroon population in the interior, also because it is not adversely affected by high water levels. The dasheen variety, commonly planted in swamps, is rare, although appreciated for its taste. The closely related Xanthosoma species is the base for the popular Surinamese dish pom. The cooked taro leaf (taya-wiri, or tayerblad) is also a well-known green leafy vegetable.

Trinidad and Tobago[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Trinidad and Tobago, it is called dasheen. The leaves of the taro plant are used to make the Trinidadian variant of the Caribbean dish known as callaloo (which is made with okra, dasheen/taro leaves, coconut milk or creme and aromatic herbs) and it is also prepared similarly to steamed spinach. The root of the taro plant is often served boiled, accompanied by stewed fish or meat, curried, often with peas and eaten with roti, or in soups. The leaves are also sauteed with onions, hot pepper and garlic til they are melted to make a dish called "bhaji". This dish is popular with Indo-Trinidadian people. The leaves are also fried in a split pea batter to make "saheena", a fritter of Indian origin.

United States[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Taro has been grown for centuries in the United States. William Bartram observed South Carolina Sea Islands residents [clarification needed: were these people Indigenous?] eating roasted roots of the plant, which they called tanya, in 1791, and by the 19th century it was common as a food crop from Charleston to Louisiana.[105] In the 1920s, dasheen[nb 1], as it was known, was highly touted by the Secretary of the Florida Department of Agriculture as a valuable crop for growth in muck fields.[107] Fellsmere, Florida, near the east coast, was a farming area deemed perfect for growing dasheen. It was used in place of potatoes and dried to make flour. Dasheen flour was said to make excellent pancakes when mixed with wheat flour.

Poi is a Hawaiian cuisine staple food made from taro. Traditional poi is produced by mashing cooked starch on a wooden pounding board (papa kuʻi ʻai), with a carved pestle (pōhaku kuʻi ʻai) made from basalt, calcite, coral, or wood.[108][109] Modern methods use an industrial food processor to produce large quantities for retail distribution. This initial paste is called paʻi ʻai.[110] Water is added to the paste during mashing, and again just before eating, to achieve the desired consistency, which can range from highly viscous to liquid. In Hawaii, this is informally classified as either "one-finger", "two-finger", or "three-finger", alluding to how many fingers are required to scoop it up (the thicker the poi, the fewer fingers required to scoop a sufficient mouthful).[111]

Since the late 20th century, taro chips have been available in many supermarkets and natural food stores, and taro is often used in American Chinatowns, in Chinese cuisine.

Venezuela[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Venezuela, taro is called ocumo chino or chino and used in soups and sancochos. Soups contain large chunks of several kinds of tubers, including ocumo chino, especially in the eastern part of the country, where West Indian influence is present. It is also used to accompany meats in parrillas (barbecue) or fried cured fish where yuca is not available. Ocumo is an indigenous name; chino means "Chinese", an adjective for produce that is considered exotic. Ocumo without the Chinese denomination is a tuber from the same family, but without taro's inside purplish color. Ocumo is the Venezuelan name for malanga, so ocumo chino means "Chinese malanga". Taro is always prepared boiled. No porridge form is known in the local cuisine.

West Indies[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Taro is called dasheen,[106] in contrast to the smaller variety of corms called eddo, or tanya in the English speaking countries of the West Indies, and is cultivated and consumed as a staple crop in the region. There are differences among the roots mentioned above: taro or dasheen is mostly blue when cooked, tanya is white and very dry, and eddoes are small and very slimy.

In the Spanish-speaking countries of the Spanish West Indies taro is called ñame, the Portuguese variant of which (inhame) is used in former Portuguese colonies where taro is still cultivated, including the Azores and Brazil. In Puerto Rico[112] and Cuba, and the Dominican Republic it is sometimes called malanga or yautia. In some countries, such as Trinidad and Tobago, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Dominica, the leaves and stem of the dasheen, or taro, are most often cooked and pureed into a thick liquid called callaloo, which is served as a side dish similar to creamed spinach. Callaloo is sometimes prepared with crab legs, coconut milk, pumpkin, and okra. It is usually served alongside rice or made into a soup along with various other roots.

Ornamental[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

It is also sold as an ornamental plant, often by the name of elephant ears. It can be grown indoors or outdoors with high humidity. In the UK, it has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[113]

Laboratory[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

It is also used for anthocyanin study experiments, especially with reference to abaxial and adaxial anthocyanic concentration.[114] A recent study has revealed honeycomb-like microstructures on the taro leaf that make the leaves superhydrophobic. The measured contact angle on the leaf in this study is around 148°.[115]

In Melissa K. Nelson's article Protecting the Sanctity of Native Foods, scientists at the University of Hawaii attempted to patent and genetically alter taro before being dissuaded by activists and farmers, "In 2006, the University of Hawaii withdrew its patents on the three varieties and agreed to stop genetically modifying Hawaii forms of taro. Researchers continue to experiment with modifying a Chinese form of taro, however."[116]

In culture[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

In Meitei mythology and Meitei folklore of Manipur, Taro (Bản mẫu:Lang-mni) plants are mentioned. One significant instance is the Meitei folktale of the [[tiếng Hanuba Hanubi Paan Thaaba|Hanuba Hanubi Paan Thaaba]] cho 'Old Man and Old Woman planting Taro'.[117][118] In this story, an old man and an old woman, were deceived by some monkeys regarding the planting of the Taro plants in a very different way.[119][120][121] The old man and woman followed the monkeys' advice, peeling off the best tubers of the plants, then boiling them in a pot until softened and after cooling them off, wrapping them in banana leaves and putting them inside the soils of the grounds.[122][123] In the middle of the night, the monkeys secretly came into the farm and ate all the well cooked plants. After their eating, they (monkeys) planted some inedible giant wild plants in the place where the old couple had placed the cooked plant tubers. In the morning, the old couple were amazed to see the plants getting fully grown up just after one day of planting the tubers. They were unaware of the tricks of the monkeys. So, the old couple cooked and ate the inedible wild Taro plants. As a reaction of eating the wild plants, they suffered from the unbearable tingling sensation in their throats.[124][125][126]

Native Hawaiians believe that the taro plant (kalo) grew out of the still-born body of one of the first two humans conceived by gods Hoʻohokukalani and Wākea;[127] thus is connected to humans more than just providing sustenance. Thus, it is often a part of sacred offerings given in ceremonies.

See also[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Notes[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

References[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- ^ T. K. Lim (3 tháng 12 năm 2014). Edible Medicinal and Non Medicinal Plants: Volume 9, Modified Stems, Roots, Bulbs. Springer. tr. 454–460. ISBN 978-94-017-9511-1.

- ^ “Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott”. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 2 năm 2015.

- ^ Umberto Quattrocchi (19 tháng 4 năm 2016). CRC World Dictionary of Medicinal and Poisonous Plants: Common Names, Scientific Names, Eponyms, Synonyms, and Etymology. CRC Press. tr. 1060–1061. ISBN 978-1-4822-5064-0.

- ^ Trần Thị, Thu; Nguyễn Thị, Xuân Viên (28 tháng 3 năm 2022). “NGHIÊN CỨU KHẢ NĂNG SINH TRƯỞNG VÀ NĂNG SUẤT CỦA MỘT SỐ GIỐNG KHOAI MÔN TRỒNG XEN TRONG VƯỜN BƯỞI GIAI ĐOẠN KIẾN THIẾT CƠ BẢN TẠI PHÚ THỌ”. Tạp chí Khoa học và Công nghệ Trường Đại học Hùng Vương. 26 (1): 51–58. ISSN 1859-3968.

- ^ Lê, Viết Bảo (2014). Nghiên cứu khả năng sinh trưởng, phát triển của một số giống khoai môn và biện pháp kỹ thuật cho giống có triển vọng tại tỉnh Yên Bái (trang 7-8) (Luận văn). Thái Nguyên: Đại học Thái Nguyên (Chuyên ngành Khoa học cây trồng). OCLC 62620110.

- ^ “Quy trình trồng và chăm sóc khoai môn?”. thuvien.mard.gov.vn. Ba Đình, Hà Nội: Thư viện Bộ Nông nghiệp và Phát triển nông thôn. 27 tháng 2 năm 2023. Truy cập ngày 26 tháng 4 năm 2024.

- ^ a b *talo: taro (Colocasia esculenta) Lưu trữ 2020-07-23 tại Wayback Machine – entry in the Polynesian Lexicon Project Online (Pollex).

- ^ Blust, Robert; Trussel, Stephen (2010). “*tales: taro: Colocasia esculenta”. Austronesian Comparative Dictionary. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 1 năm 2023.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2009). “Vernacular Names for Taro in the Indo-Pacific Region and Their Possible Implications for Centres of Diversification and Spread” (PDF).

- ^ a b “Saru Patra Tarkari: A Classic Odia Dish Using Colocasia Leaves”. Goya. 13 tháng 8 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 12 tháng 11 năm 2022.

- ^ natong.

- ^ “Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott - Names of Plants in India”. sites.google.com. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 22 tháng 4 năm 2023.

- ^ Jha, Shailee (8 tháng 11 năm 2021). “अरीकंचन की सब्जी | Traditional Mithila Curry Recipe”. CandidTreat (bằng tiếng Anh). Truy cập ngày 28 tháng 8 năm 2022.

- ^ Ministry of Education, R.O.C. “臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典”.

- ^ “vasa”. 原住民族語言線上詞典 (bằng tiếng Trung). Council of Indigenous Peoples. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 23 tháng 8 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 1 năm 2021.

- ^ “tali”. 原住民族語言線上詞典 (bằng tiếng Trung). Council of Indigenous Peoples. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 23 tháng 8 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 1 năm 2021.

- ^ Fey, Virginia (2018). Amis Dictionary. The Bible Society in Taiwan. Truy cập ngày 1 tháng 1 năm 2021.

- ^ Clark, Ross (2009). Leo Tuai: A comparative lexical study of North and Central Vanuatu languages. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. doi:10.15144/PL-603. ISSN 1448-8310.

- ^ Ross, Malcolm D.; Andrew Pawley; Meredith Osmond (1998). The lexicon of Proto-Oceanic: Volume 1, Material culture (PDF). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 9780858835078. OCLC 470523930.

- ^ “Madumbi”. Taste. Truy cập ngày 12 tháng 11 năm 2022.

- ^ “iteke (ama-)”. Kinyarwanda. Truy cập ngày 12 tháng 11 năm 2022.

- ^ LaSur, Lee Yan (12 tháng 10 năm 2023). “St Vincent Dasheen exporters receive post-harvest management training”. St Vincent Times. St Vincent. Truy cập ngày 12 tháng 10 năm 2023.

- ^ Dastidar, Sayantani Ghosh (tháng 12 năm 2009). Colocasia esculenta: An account of its ethnobotany and potentials (PDF). The University of Texas at Austin. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 8 năm 2017.[liên kết hỏng]

- ^ “Trinidad Bhagi”. 13 tháng 11 năm 2020.

- ^ “Modulo de Formação Técnicos de Extensão Agrícola em África”. FAO (bằng tiếng Bồ Đào Nha). 2003. Truy cập ngày 7 tháng 4 năm 2021.

- ^ Fernandes, Daniel. “Produtos Tradicionais Portugueses”. Produtos Tradicionais Portugueses (bằng tiếng Bồ Đào Nha).

- ^ “Malanga - Spanish to English Translation | Spanish Central”. www.spanishcentral.com.

- ^ “Malanga | Definición de Malanga por Oxford Dictionaries en Lexico.com también significado de Malanga”. Lexico Dictionaries | Spanish (bằng tiếng Tây Ban Nha). Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 20 tháng 8 năm 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879). A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Keimer, Ludwig (1984). Die Gartenpflanzen im alten Ägypten. 2. Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe. tr. 62.

- ^ “Elephant Ears (Colocasia, Alocasia, and Xanthosoma)”. Master Gardener Program (bằng tiếng Anh). Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 11 tháng 11 năm 2020.

- ^ Albert F. Hill (1939), “The Nomenclature of the Taro and its Varieties”, Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, 7 (7), tr. 113–118, doi:10.5962/p.295132

- ^ Kolchaar, K. 2006 Economic Botany in the Tropics, Macmillan India

- ^ “Colocasia esculenta”. Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Cục Nghiên cứu Nông nghiệp (ARS), Bộ Nông nghiệp Hoa Kỳ (USDA).

- ^ “Γαστρονομία | Visit Ikaria”. www.visitikaria.gr. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 3 năm 2023.

- ^ “Invasive Plants to Watch for in Georgia” (PDF). Georgia Invasive Species Task Force. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 8 năm 2015.

- ^ Colocasia esculenta.

- ^ Colocasia esculenta, Florida Invasive Plants

- ^ Colocasia esculenta Lưu trữ 2015-06-26 tại Wayback Machine, University of Florida

- ^ “Wild Taro”. Outdoor Alabama. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 9 năm 2020.

- ^ Denham, Tim (tháng 10 năm 2011). “Early Agriculture and Plant Domestication in New Guinea and Island Southeast Asia”. Current Anthropology. 52 (S4): S379–S395. doi:10.1086/658682.

|hdl-access=cần|hdl=(trợ giúp) - ^ new-agri.co Country profile: Samoa, New Agriculturist Online Lưu trữ 2008-08-28 tại Wayback Machine, accessed June 12, 2006

- ^ Kreike, C.M.; Van Eck, H.J.; Lebot, V. (20 tháng 5 năm 2004). “Genetic diversity of taro, Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott, in Southeast Asia and the Pacific”. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 109 (4): 761–768. doi:10.1007/s00122-004-1691-z. PMID 15156282.

- ^ Lebot, Vincent (2009). Tropical Root and Tuber Crops: Cassava, Sweet Potato, Yams and Aroids. Crop Production Science in Horticulture. 17. CABI. tr. 279–280. ISBN 9781845936211.

- ^ Chaïr, H.; Traore, R. E.; Duval, M. F.; Rivallan, R.; Mukherjee, A.; Aboagye, L. M.; Van Rensburg, W. J.; Andrianavalona, V.; Pinheiro de Carvalho, M. A. A.; Saborio, F.; Sri Prana, M. (17 tháng 6 năm 2016). “Genetic Diversification and Dispersal of Taro (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott)”. PLOS ONE. 11 (6): e0157712. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157712C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157712. PMC 4912093. PMID 27314588.

- ^ Matthews, Peter J.; Nguyen, Van Dzu; Tandang, Daniel; Agoo, E. Maribel; Madulid, Domingo A. (2015). “Taxonomy and ethnobotany of Colocasia esculenta and C. formosana (Araceae): implications for the evolution, natural range, and domestication of taro”. Aroideana. 38E (1). Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 19 tháng 1 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 18 tháng 1 năm 2019.

- ^ Matthews, P.J.; Agoo, E.M.G.; Tandang, D.N.; Madulid, D.A. (2012). “Ethnobotany and Ecology of Wild Taro (Colocasia esculenta) in the Philippines: Implications for Domestication and Dispersal” (PDF). Trong Spriggs, Matthew; Addison, David; Matthews, Peter J. (biên tập). Irrigated Taro (Colocasia esculenta) in the Indo-Pacific: Biological, Social and Historical Perspectives. Senri Ethnological Studies (SES). 78. National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka. tr. 307–340. ISBN 9784901906937. Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 19 tháng 1 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 18 tháng 1 năm 2019.

- ^ a b Barker, Graeme; Lloyd-Smith, Lindsay; Barton, Huw; Cole, Franca; Hunt, Chris; Piper, Philip J.; Rabett, Ryan; Paz, Victor; Szabó, Katherine (2011). “Foraging-farming transitions at the Niah Caves, Sarawak, Borneo”. Antiquity. 85 (328): 492–509. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00067909.

- ^ Balbaligo, Yvette (15 tháng 11 năm 2007). “A Brief Note on the 2007 Excavation at Ille Cave, Palawan, the Philippines”. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology. 18 (2007): 161. doi:10.5334/pia.308.

- ^ Fullagar, Richard; Field, Judith; Denham, Tim; Lentfer, Carol (tháng 5 năm 2006). “Early and mid Holocene tool-use and processing of taro (Colocasia esculenta), yam (Dioscorea sp.) and other plants at Kuk Swamp in the highlands of Papua New Guinea”. Journal of Archaeological Science. 33 (5): 595–614. Bibcode:2006JArSc..33..595F. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.07.020.

- ^ Denham, Tim P.; Golson, J.; Hughes, Philip J. (2004). “Reading Early Agriculture at Kuk Swamp, Wahgi Valley, Papua New Guinea: the Archaeological Features (Phases 1–3)”. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 70: 259–297. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00001195.

- ^ Loy, Thomas H.; Spriggs, Matthew; Wickler, Stephen (1992). “Direct evidence for human use of plants 28,000 years ago: starch residues on stone artefacts from the northern Solomon Islands”. Antiquity. 66 (253): 898–912. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00044811.

- ^ Barker, Graeme; Hunt, Chris; Carlos, Jane (2011). “Transitions to Farming in Island Southeast Asia: Archaeological, Biomolecular and Palaeoecological Perspectives” (PDF). Trong Barker, Grame; Janowski, Monica (biên tập). Why cultivate? Anthropological and Archaeological Approaches to Foraging–Farming Transitions in Southeast Asia. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. tr. 61–74. ISBN 9781902937588.

- ^ Matthews, Peter J. (1995). “Aroids and the Austronesians”. Tropics. 4 (2/3): 105–126. doi:10.3759/tropics.4.105.

- ^ Barton, Huw (2012). “The reversed fortunes of sago and rice, Oryza sativa, in the rainforests of Sarawak, Borneo” (PDF). Quaternary International. 249: 96–104. Bibcode:2012QuInt.249...96B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.03.037.

- ^ Moore, Darlene (14 tháng 10 năm 2019). “Ancient Chamorro Agricultural Practices”. Guampedia.

- ^ Dixon, Boyd; Walker, Samuel; Golabi, Mohammad H.; Manner, Harley (2012). “Two probably latte period agricultural sites in northern Guam: Their plants, soils, and interpretations” (PDF). Micronesica. 42 (1/2): 209–257.

- ^ McLean, Mervyn (2014). Music, Lapita, and the Problem of Polynesian Origins. Polynesian Origins. ISBN 9780473288730.

- ^ Sanderson, Helen (2005). Prance, Ghillean; Nesbitt, Mark (biên tập). The Cultural History of Plants. Routledge. tr. 70. ISBN 0415927463.

- ^ a b Oladimeji, J.J.; Kumar, P.L.; Abe, A.; Vetukuri, R.R.; Bhattacharjee, R.(2022).

- ^ “Production of taro in 2022, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity/Year (pick lists)”. UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2024. Truy cập ngày 22 tháng 1 năm 2024.

- ^ Jennings, D. (2009). Tropical Root and Tuber Crops. Cassava, Sweet Potato, Yams and Aroids. By V. Lebot. Wallingford, UK: CABI (2009), pp. 413. ISBN 978-1-84593-424-8. Experimental Agriculture, 45(3). doi:10.1017/S0014479709007832

- ^ Bussell, W.T., Scheffer, J.J.C. and Douglas, J.A. (2004). Recent research on taro production in New Zealand. In: Guarino, L., Taylor, M. and Osborn, T. (eds) Proceedings of the 3rd Taro Symposium. Secretariat of the Pacific Community, Nadi, Fiji, pp.

- ^ a b c d e Lebot, Vincent (2020). Tropical rooT and Tuber crops Cassava, Sweet Potato, Yams and Aroids (bằng tiếng English) (ấn bản 2). France: Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement France. tr. 359–382. ISBN 9781789243376.Quản lý CS1: ngôn ngữ không rõ (liên kết)

- ^ Lebot, V.; Tuia, V.; Ivancic, A.; và đồng nghiệp (5 tháng 9 năm 2017). “Adapting clonally propagated crops to climatic changes: a global approach for taro (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott)”. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (bằng tiếng Anh). 65 (2): 591–606. doi:10.1007/s10722-017-0557-6. hdl:10400.13/3170. ISSN 0925-9864. S2CID 12700604.

- ^ a b United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). “Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels”. Truy cập ngày 28 tháng 3 năm 2024.

- ^ a b National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (biên tập). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154.Quản lý CS1: nhiều tên: danh sách tác giả (liên kết)

- ^ “new-agri.co.uk”. www.new-agri.co.uk. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 6 năm 2024.

- ^ McGee, Harold. On Food and cooking. 2004. Scribner, ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1

- ^ “Weird Foods from around the World”. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 11 tháng 4 năm 2008. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 4 năm 2008.

- ^ “Elephant Ears”. ASPCA.

- ^ The Morton Arboretum Quarterly, Morton Arboretum/University of California, 1965, p. 36.

- ^ FAO. “Taro Cultivation in Asia and the Pacific”. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 24 tháng 11 năm 2007. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 6 năm 2016.

- ^ “Rukau – A simple delight”. Cook Islands News. 14 tháng 1 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 1 năm 2021.

- ^ Taro leaf blight caused by Phytophthora colocasiae, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources (CTAHR), University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, Honolulu, Hawai'i, p. 2.

- ^ a b Viotti 2004.

- ^ a b Hao 2006.

- ^ “Taro in Hawaiian Culture”. Hawaii Luaus. 21 tháng 2 năm 2020. Truy cập ngày 12 tháng 11 năm 2022.

- ^ Kameʻeleihiwa, Lilikala (2008). Hawaii: Center of the Pacific. Acton, MA: Copley Custom Textbooks. tr. 57.

- ^ Beckwith, Martha Warren (31 tháng 12 năm 1970). “Papa and Wakea”. Hawaiian Mythology. Honolulu: University of Hawaii. tr. 94. doi:10.1515/9780824840716. ISBN 978-0-8248-4071-6. OCLC 1253313534.

- ^ “Hawaiian kalo history”. hbs.bishopmuseum.org. 18 tháng 4 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 17 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- ^ Heard, Barbara H. (7 tháng 11 năm 2011). “HALOA”. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 4 tháng 8 năm 2012. Truy cập ngày 7 tháng 2 năm 2012.

- ^ “Taro creation story — Hawaii SEED”. 7 tháng 11 năm 2011. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 25 tháng 4 năm 2012. Truy cập ngày 7 tháng 2 năm 2012.

- ^ “Taro: Hawaii's Roots”. earthfoot.org. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 3 tháng 3 năm 2012.

- ^ Robbins, Joel (1995). “Dispossessing the Spirits: Christian Transformations of Desire and Ecology among the Urapmin of Papua New Guinea quick view”. Ethnology. 34 (3): 212–213. doi:10.2307/3773824. JSTOR 3773824.

- ^ The Japan Times Online

- ^ “Laing, gabi”. Flickr. tháng 3 năm 2008.

- ^ “Real Estate Guide Plano – Hottest Deals On Market”. Real Estate Guide Plano. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 13 tháng 9 năm 2011.

- ^ “How to Make Coconut and Taro Ice Cream – A Thai Classic Dessert”. Pinterest. 18 tháng 3 năm 2013.

- ^ Kitchen, Archana's. “Arbi Gosht Masala Recipe - Mutton Arbi Curry In Electric Pressure Cooker”. Archana's Kitchen.